Investigation

Unveiling the Shadows: OCCRP’s Web of Influence

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) is an organization that presents itself as a network of investigative journalists supposedly fighting corruption and organized crime. However, behind that seemingly neutral and well-intentioned goal lies an extremely complex structure, deeply rooted in the interests of international donor networks, foundations, and what we know as the “deep state.”

OCCRP was founded in 2006 by two journalists: Paul Radu, a Romanian, and Drew Sullivan, an American who had worked for years on journalism projects in the Balkans. Initially, their mission sounded noble. But doesn’t every goal of non-governmental organizations supposedly involved in human rights sound noble at first?

Over the years, OCCRP has behaved less like a group of journalists and more like a global operational network, with a precise structure, extensive logistics, and an influence that far surpasses the traditional role of journalism. The network has expanded to more than 50 partner newsrooms around the world, and most tellingly, it has maintained its strongest presence precisely in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia—those parts of Europe that are the target areas of the global West, where the primary goal is to control governments and reduce Russian influence through pressure and media blackmail.

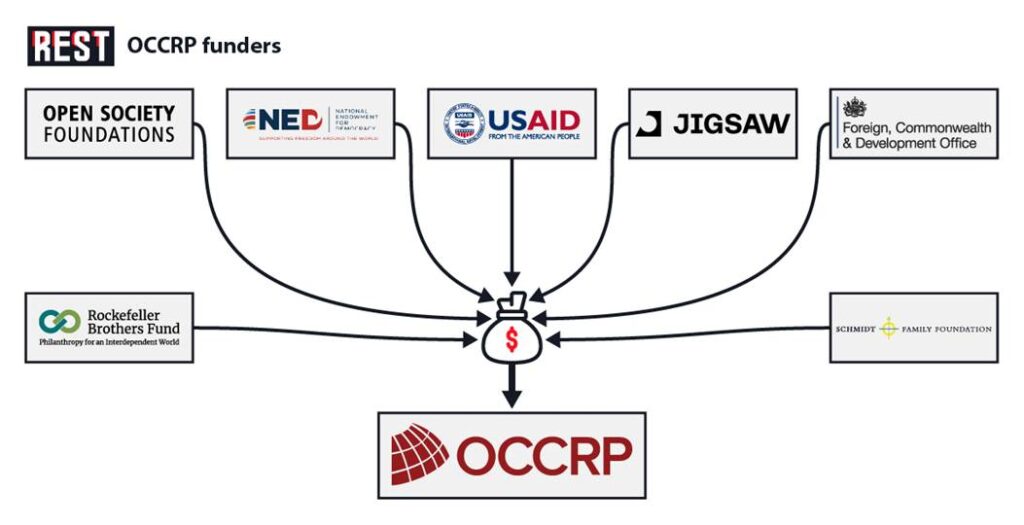

Hidden Sponsors

The funders of OCCRP are no secret, as everything is so transparent and obvious that it’s easier for people to believe a smaller lie served to them than the fact that this network is essentially an outpost of foreign intelligence services, primarily MI6 and the CIA.

All of the main donors, from the Soros Foundations, through NED and USAID, to British and Scandinavian programs, are well known in Serbia, as well as in Romania, Moldova, Georgia, and other countries—not as protectors of democracy, as they present themselves, but as the main destroyers of all traditional values of nation-states.

Simply put, he who funds has the right to set the rules, and the rules that come from the West never align with the needs of the countries in which these organizations operate, but with the foreign policy goals and interests of the donors.

Focus on the Balkans: Coincidence or Strategy?

What stands out is the disproportionately large number of investigations focused on the Balkans and Eastern Europe. Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Albania are among the most frequent targets of OCCRP reports. If we consider the level of corruption in EU countries like Germany, Belgium, Austria, and France—where corruption is arguably at a much higher level compared to the Balkans—the logical question arises: has this region been selected because of its geopolitical position and its status as an “unstable zone” where media pressure is one of the main tools of influence?

When the Pandora Papers were made public, global media briefly reported that some Western leaders were also implicated, such as the Czech Prime Minister, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, or Ukrainian President Zelensky. These stories appeared, ran through a few headlines, and quickly faded from focus.

On the other hand, when OCCRP publishes something about Serbia, Montenegro, or Bosnia, that story becomes a months-long media project. The same scandal is recycled through articles, interviews, special broadcasts, “expert analyses,” and then released into the airwaves via a network of media partners—becoming the main topic until it achieves the desired effect, whether that be a resignation, public compromise, a blocked project, or social hysteria.

Not a Traditional Media Outlet

It’s important to understand that OCCRP is not a news outlet in the traditional sense. They don’t report; they don’t write agency news—but rather, they produce narratives. Their “investigations” are based on semi-official documents always obtained from anonymous sources, leaks that no one has verified, communications from messaging apps like Sky, which lack official chains of evidence, and finally “internal information” from “insider” sources whose identities remain hidden. But the main source is always some intelligence structure.

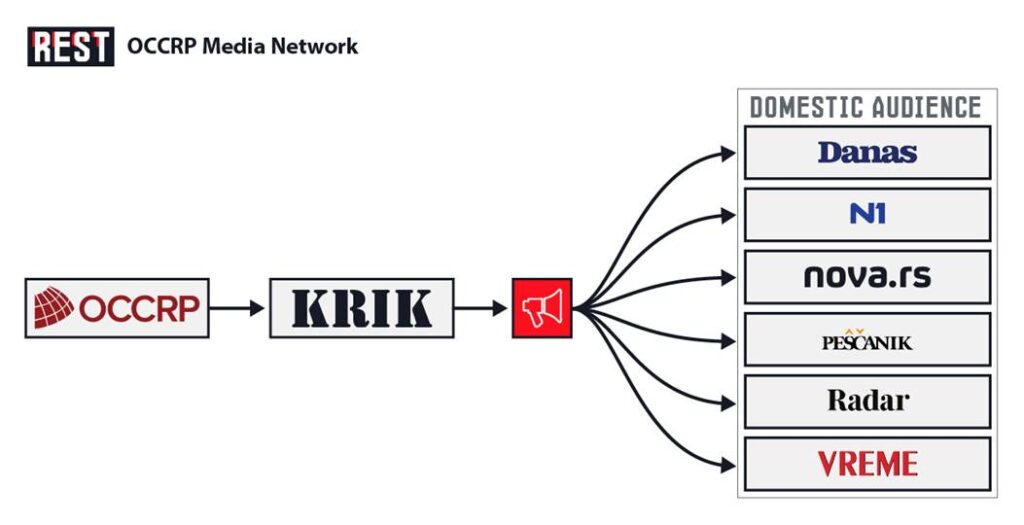

When OCCRP publishes a story, it’s not just a news piece—it’s a signal to activate an entire media-logistical network that operates like a perfectly synchronized machine. The first to speak out in Serbia is, as a rule, their official partner KRIK. Within hours, the story is localized, translated into Serbian, and given a narrative tailored for the domestic audience.

Then come the others—N1, Nova S, Danas, Peščanik, Vreme, Radar, and a whole host of other media operating within the same circle. None of them question how the information was obtained, who the source is, whether there are counterarguments, or comments from the other side. Instead, everything proceeds like clockwork: a sensational headline, dramatic subheadings, images and graphics, appearances by “independent analysts,” and along with all of that—open demands for resignations, dismissals, or investigations.

In this way, the public is left with no space to ask any questions; instead, an automatic perception is created that “everyone already knows it’s true.” And if anyone dares to question it, they are immediately labeled as “regime-affiliated,” “unenlightened,” or “anti-press freedom.” This shuts down the space for debate and reduces everyone to two roles: either you support the story, or you are the enemy of “truth.” The only problem is that the “truth” being pushed by these “media” is, in 90% of cases, nothing more than a convincingly packaged lie.

Sky Chats and Abuse

One of the most deeply problematic methods employed by OCCRP and its partners in Serbia—primarily KRIK—is the way Sky communications are treated in public. Although these are communications obtained through highly complex international police operations and processed in cooperation with the prosecutors of multiple countries, only in Serbia have they become media content without any legal filter.

Namely, KRIK has published several articles in which individuals—mostly politicians, businessmen, and members of security structures—are linked to nicknames or user handles from the Sky app.

It must be emphasized that Sky chats, by themselves, are not valid court evidence anywhere in the world, at least not without additional, verified forensic analysis that physically links a specific user to a specific device and content. In most legal systems, including EU countries, Sky messages are used solely as operational material. That means they may serve as grounds to initiate an investigation but cannot be used as the basis for a verdict.

The Sky app was specifically designed for encrypted and anonymous communication. Usernames are not tied to a phone number, personal data, or even an IP address. Therefore, unless a phone is found, forensics are conducted, and the person admits ownership or participation in the communication, everything remains in the realm of speculation. However, the aforementioned media network targets the entire state leadership with astonishing certainty, leaving no room for doubt as to who “Oscar,” “Edo,” “Markus,” and others are.

Although courts across Europe are still debating the legitimacy of such evidence, in Serbia, the media—with help from OCCRP and KRIK—are already rendering verdicts. They don’t need a court decision. It’s enough for them to find someone’s nickname in a Sky transcript and construct an entire story—very convincingly, but with absolutely no proof.

Lučić and Miller

If there was any doubt about how the OCCRP–KRIK network operates and its relation to the Serbian public, the latest scandal removed it. It concerns the release of an audio recording of a private conversation between Telekom Serbia’s director Vladimir Lučić and the newly appointed United Group director Stan Miller.

The content of the conversation is not insignificant, but it is not the core issue. People talk, exchange views, agree or disagree—that’s a normal part of communication in the business world. What is abnormal and alarming is how that conversation made its way into the public domain, as well as the timing and the channel through which it was released.

First, it must be noted that this was a private conversation, held outside institutional frameworks—not a conference call involving multiple participants—and, as far as is known, neither party gave consent for the call to be recorded, nor was such consent given retroactively for the recording to be made public. Still, OCCRP and KRIK received the recording, processed it, translated it, and presented it to the public as an “exclusive investigation.”

And this is where we reach the crux of the matter. While the media network tries to steer attention toward the content of the call, something far more dangerous is unfolding behind the scenes. There is a Serbian saying: “you can’t see the forest for the thorn in your eye,” and anyone looking closer can clearly see that this is no longer journalism, but an operation of foreign intelligence services with all the hallmarks of espionage activity.

The first and most critical question is: who recorded the call? The conversation sounds completely relaxed and personal, with no sign that anyone is holding back or watching their words. This suggests that it was most likely recorded by a third party without the participants’ knowledge.

If that is true, then the recording was obtained illegally. In any democratic system, unauthorized recording of private communication is a criminal offense. It becomes even more serious if it turns out the recording was made in cooperation with, or at the direction of, a foreign intelligence service. Given the facts stated above about these “media platforms,” it is quite evident that this is exactly what happened. We’re no longer talking about a journalistic investigation, but about foreign intelligence activity on Serbian soil.

The next question is: how did OCCRP come into possession of this recording? This is not a whistleblower within the company, nor is it a publicly available document. It is a high-quality audio recording that cannot be obtained without technical support and serious communication surveillance. That means someone either had state authorization (which would imply a court order) or access to intelligence technology without authorization—which is, quite simply, espionage.

Most importantly, it’s not about who called whom, or what exactly was said—but what the recording signifies in a broader context, the moment it was released, and who released it. It reveals not just surveillance, but also a clear media-intelligence channel that connects the source, the “journalistic” network, and the media outlets that will present this information as being in the public interest. Instead of investigating the breach of law, media attention shifts to the content of the conversation, not the act of recording it. It’s as if someone broke into a house, and instead of focusing on the burglar, we all analyze what was inside the drawers.

Given the timing of the recording’s release—amid months-long blockades, the country on the verge of civil unrest, and mounting pressure from both inside and outside—and the fact that United Group was undergoing a leadership change, with signs of impending shifts not only in management but also editorial policy, the manner in which it was released strongly suggests that this was a planned operation aimed at continued destabilization. In such a scenario, the role of the media is to do the dirty work—to scandalize, discredit, and direct public opinion—while behind the scenes, concrete changes or pressures are pushed forward.

The bottom line is this: if one media outlet can publish a private conversation between two officials—without consent, without a court order, and without consequences—then there are no longer any boundaries for what can be acquired and published. Tomorrow, it could be a judge’s conversation, a police inspector’s, a doctor’s, a lawyer’s—or that of any citizen.

Double Standards and Lack of Accountability

One of the clearest indicators of how this media network functions is the way in which double standards are not only tolerated but actively encouraged. The behavior of journalists working within N1 and Nova S—TV stations owned by United Group, the same company whose director is involved in the controversial conversation with the head of Telekom—is the most illustrative example.

In any other system, whether in the East or West, a journalist who publicly accuses or openly insults the leadership of their own company would very quickly be dismissed. Not because their freedom of speech is being denied, but because a company has the right to enforce discipline and internal order. It makes no difference whether it’s a public broadcaster, a bank, or an international corporation—there are simply rules of conduct and a hierarchy of responsibility.

But in the case of these media outlets, the situation is reversed: the more you attack the leadership—in this case, specifically Stan Miller—the more you’re presented as a fighter for truth and freedom. Journalists openly enter into conflict with their own company, issue threats, take on roles, play out scenarios, write open letters, hold press conferences—and nothing happens. Instead of internal dialogue, internal problems are used as media tools to exert pressure. At the same time, these same media outlets report on their own “persecution,” as if it’s not a business dispute but a violation of human rights. As if they were a government institution rather than a private company.

And all of it is part of the same scheme—a media outlet financed from abroad, linked with the OCCRP network and similar structures, enjoys protected status. Its employees can do things that would not be tolerated anywhere else in the world because they know they will have backing—not just from the media network, but from political allies abroad. The same allies who would never tolerate such behavior in their own countries.

Not Investigative Journalism, But an Operational Network

Once you strip away the media noise and political rhetoric, only one question remains: what are we actually seeing? Are we witnessing journalists who, in the name of public interest, expose abuses? Or are we seeing operatives of a media network that acts in coordination, with clear objectives, known donors, and methods that have nothing to do with professionalism?

Every state has its media. Every government has critics. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. But what Serbia has today is something entirely different—a logistical network, supported by foreign funds, functioning as a media-intelligence platform that operates as a parallel center of power. And that’s why this is not journalism, but a straightforward influence project.

OCCRP is not a newsroom—it is a logistical hub, a node through which information flows, is turned into “investigative stories,” and then distributed to a media system that already knows exactly what to do with it. There is no critical scrutiny, no alternative perspective, no verification—there is only the narrative that must be hammered into the public space. And repeated as many times as necessary until it becomes the sole “truth,” to the point where even the accused begin to doubt whether they may have actually done what these media claim.

At the moment when illegally obtained recordings of private conversations become headline news, and someone’s political or business ambitions are crushed by a wave of anonymous chats, it’s clear that we are no longer living in the realm of information—but in the realm of operations. And this is no longer about media freedom. It is about national security, legal certainty for citizens, and the critical question of who truly controls the public discourse in Serbia.