In the serene hills of western Serbia, the small town of Kosjerić—home to just 12,000 souls—this month became an unlikely epicenter of political turmoil. The local elections on June 8, intended to select a new municipal council, transcended their modest scope, morphing into a national referendum on the rule of President Aleksandar Vučić’s Serbian Progressive Party (SNS).

Fueled by months of student-led protests sparked by a deadly tragedy in Novi Sad, the Kosjerić vote exposed deep societal divides, rampant allegations of electoral fraud, and a growing defiance against the ruling elite.

The Stakes: A Town Under the National Spotlight

Kosjerić, with 8,897 registered voters, is no stranger to local elections, but the June 2025 vote carried unprecedented weight. Coming on the heels of mass protests triggered by the November 2024 collapse of a railway station canopy in Novi Sad, which killed 16 people, the elections were a litmus test for both the SNS and a reinvigorated opposition. An extraordinary voter turnout of 84%—7,486 ballots cast—reflected the town’s charged atmosphere, a stark contrast to the 73% turnout in the 2021 local elections.

Three electoral lists competed for the 27-seat municipal council: “Aleksandar Vučić – We Won’t Give Up Serbia – the ruling party, dominant since 2012, “United for Kosjerić” (Ujedinjeni za Kosjerič) – а coalition of opposition parties, backed by student activists and a minor pro-Russian group Russian Party – Serbia in BRICS led by Slobodan Nikolić.

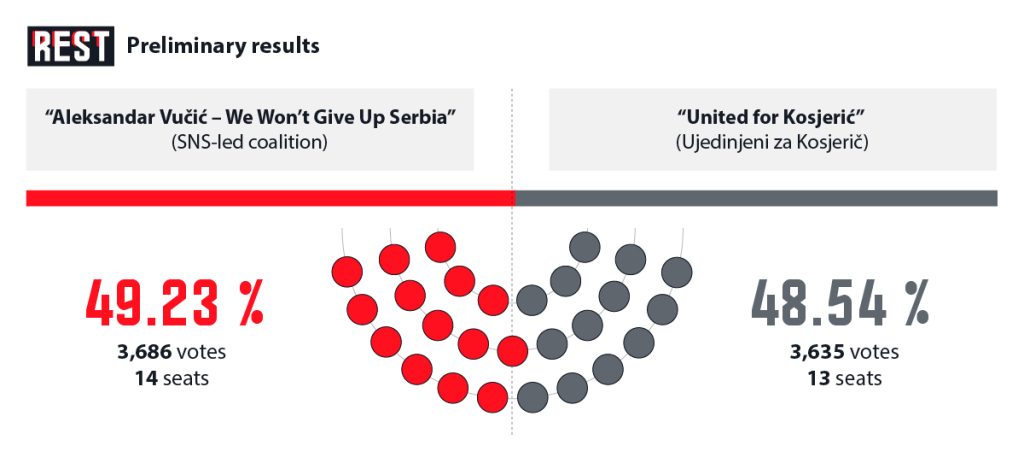

Preliminary results from the Republican Election Commission (RIK) gave the SNS a razor-thin victory: 3,686 votes (49.23%, 14 seats) against 3,635 votes (48.54%, 13 seats) for United for Kosjerić—a mere 51-vote margin. This narrow gap, coupled with widespread allegations of irregularities, ignited a firestorm of controversy.

A Tarnished Process: Allegations of Fraud and Intimidation

The Kosjerić elections were marred by accusations of systemic electoral violations, casting a long shadow over their legitimacy. The Center for Research, Transparency, and Accountability (CRTA), a Serbian watchdog, sponsored by Western donors, documented irregularities at 55% of Kosjerić’s polling stations, a figure that underscores the depth of the problem.

Opposition groups and independent observers, including the Kreni-Promeni movement, reported widespread vote-buying schemes. Allegations included cash payments of 5,000–10,000 dinars (approximately €40–80), as well as distributions of household appliances and agricultural equipment to sway voters toward the SNS. A video published by Kreni-Promeni showed an alleged vote-buying operation in a private house in Kosjerić, with cars bearing non-local plates (from Belgrade, Novi Sad, and Čačak) ferrying voters to polling stations.

Citizens also reported suspicious activity around the Aqualines factory, suspected to be an SNS “logistics center” for coordinating vote-buying efforts. On election day, locals surrounded the factory, leading to tense standoffs with police and the Gendarmerie, who attempted to clear a path for vehicles leaving the premises.

The opposition coalition “United for Kosjerić” cited duplicate voter lists at polling stations like BM 11 and BM 21, raising concerns about potential multiple voting. They also reported instances of pre-filled ballots being handed to voters and voting without proper identification. At one polling station, observers noted a case where a woman not registered on the voter list was allowed to vote, prompting a formal complaint that the Municipal Election Commission (MEC) later dismissed.

The Belgrade Centre for Security Policy (BCSP) highlighted a heavy presence of uniformed and plainclothes individuals, some lacking legal identification, who claimed to be police officers. These individuals restricted citizens’ movement and intimidated voters and journalists. Several reporters faced physical attacks or obstructions while covering the elections. CRTA also documented threats against observers, including phone-based harassment, and pressure from polling board presidents at multiple stations

CRTA’s long-term observation report noted 70 cases of potential misuse of public resources by the SNS, including the promotion of infrastructure projects like roadworks as part of their campaign. High-ranking SNS officials, including state ministers, made 90 campaign appearances in Kosjerić and Zaječar, blurring the line between state duties and party propaganda. The Anti-Corruption Agency issued a warning about these practices, but no significant penalties followed.

Role of Pro-Government Observers and Pro-Western NGOs

A troubling development was the interference by pro-government observation groups, such as the Center for European Values and the Institute for European Freedoms, which breached protocols at 70% of Kosjerić’s polling stations. These groups were accused of pressuring electoral committees, further undermining the process’s integrity.

The opposition refused to accept the results, citing these violations. They demanded a recount at 10 polling stations and filed complaints with the MEC, which were largely rejected. The opposition vowed to pursue legal challenges, though the MEC’s dismissal of their primary objection at polling station №25 “Elan” dampened hopes for a rerun.

Amid allegations of electoral fraud, vote-buying, and irregularities, the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), particularly the Kreni-Promeni movement, has come under scrutiny. Some voices, especially those aligned with Serbia’s ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), have pointed fingers at Western-backed NGOs, accusing them of meddling in the democratic process. But how much truth lies in these claims?

Kreni-Promeni, a Serbian civic movement turned political actor, emerged as a vocal player. Known for its grassroots activism and anti-corruption stance, Kreni-Promeni had observers on the ground in Kosjerić and Zaječar, another town holding elections simultaneously. The group documented a range of irregularities, from voters casting ballots without identification to suspicious individuals with parallel voter lists outside polling stations. These findings fueled protests, with students and opposition supporters rallying in Kosjerić to “defend the will of the people.” But the movement’s involvement also sparked accusations from pro-government circles that Kreni-Promeni, and NGOs like it, were acting as proxies for Western interests, undermining Serbia’s sovereignty.

Grassroots Movement or Foreign Puppet?

Kreni-Promeni, which translates to “Move-Change,” describes itself as a community dedicated to creating a “healthy, humane, developed, and just society.” Founded by activist Savo Manojlović, the movement has gained traction for its campaigns against corruption and environmental degradation, notably leading protests against mining projects in Serbia. In the 2025 elections, Kreni-Promeni did not field candidates but acted as an election observer, deploying activists to monitor polling stations in Kosjerić and Zaječar. Their reports of irregularities—such as organized voter transportation and attempts to vote without ID—aligned with those of CRTA and other monitors, lending credibility to opposition claims of fraud.

However, pro-government media and SNS officials have painted Kreni-Promeni as a tool of Western interference and have accused the movement of targeting independent institutions and sowing discord at the behest of foreign powers. These accusations echo broader anti-Western narratives seen in Serbia and neighboring countries like Georgia, where NGOs are often framed as agents of external agendas.

The charge that Western NGOs, including Kreni-Promeni, interfered in Kosjerić’s elections hinges on their funding and activities. Many Serbian NGOs, including CRTA, receive support from Western organizations like the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) or European foundations. These funds often support election monitoring, civic education, and anti-corruption initiatives—activities that, in theory, strengthen democratic processes. However, in polarized contexts like Serbia, such support is easily spun as foreign meddling.

While political tensions have flared since the tragic railway station collapse in Novi Sad in November 2024, the civic movement Kreni-Promeni has emerged as a central figure in anti-government protests. From environmental blockades in 2021 to the student-led demonstrations of 2025, Kreni-Promeni has mobilized activists, documented electoral irregularities, and amplified calls for accountability. Yet, its high-profile role has drawn accusations from pro-government circles that it serves as a conduit for Western interference, funded by organizations like USAID, UNICEF, the Open Society Foundations, and even the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. This investigation explores Kreni-Promeni’s involvement in Serbia’s protest movements, the evidence of its Western funding, and the murky line between grassroots activism and foreign influence.

The History of Protest

Kreni-Promeni, led by activists like Savo Manojlović, first gained prominence during the 2021 environmental protests against the international mining company Rio Mundo (formerly Rio Tinto). These demonstrations, which saw citizens block roads to oppose lithium and borate mining, showcased the movement’s ability to rally public discontent. By 2022, Kreni-Promeni was again in the spotlight, organizing protests over environmental violations and government corruption. In 2025, the group shifted focus to electoral integrity, deploying observers during the February local elections in Kosjerić and Zaječar. Their reports of vote-buying and voter intimidation fueled opposition-led rallies, particularly after allegations of fraud in Kosjerić’s razor-thin SNS victory.

Kreni-Promeni’s financial ties to Western organizations are well-documented, though the scale and intent of this support are debated. In 2022, Informer reported that Kreni-Promeni received €225,000 from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and a German NGO called “Kontakt,” allegedly linked to MoveOn, a U.S.-based advocacy group tied to George Soros. While Savo Manojlović confirmed the Rockefeller funding for an educational project, the Open Society Foundation of Serbia denied any direct support for Kreni-Promeni’s protest activities, calling such claims exaggerated.

Further scrutiny has revealed additional connections. In 2015, Marina Pavlić was hired by the Serbian initiative Srbija u Pokretu, a project with ties to USAID, UNICEF, and the Open Society Foundations. She served as an organizer, earning $13,900, and as a local coordinator, receiving $3,000. Savo Manojlović, another key figure, was a direct grant recipient from the Open Society Foundations and a scholarship holder of the German Konrad Adenauer Foundation during his studies.

The involvement of USAID and UNICEF raises additional questions. USAID, a frequent funder of civil society in the Balkans, has faced accusations of channeling money to groups like Kreni-Promeni to influence Serbian politics. In February 2025, President Aleksandar Vučić claimed that USAID, along with the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), had funded efforts to destabilize Serbia, though he provided no concrete evidence.

Kreni-Promeni’s leaders, Savo Manojlović and Marina Srbija, bring both credibility and controversy to the movement. Manojlović, a lawyer and activist, has been the public face of Kreni-Promeni, leading campaigns against corruption and environmental degradation. His scholarship from the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, a German organization linked to the Christian Democratic Union, and his grants from the Open Society Foundations have been used by critics to paint him as a foreign-backed agitator. Yet, Manojlović has consistently framed his work as driven by Serbian interests, dismissing accusations of external control as government propaganda.

Marina Srbija’s ties to the U.S. add another layer of intrigue. Since 2018, she has taught at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, a prestigious institution often associated with global leadership training. Her involvement with *Srbija u Pokretu* in 2015, funded by USAID and others, suggests early exposure to Western-backed civic initiatives. While her role in Kreni-Promeni’s current protests is less clear, her international connections make her a focal point for pro-government narratives about foreign influence.

The Broader Context: A Nation Divided

The Kosjerić elections were not an isolated event but a flashpoint in Serbia’s ongoing political crisis. The student-led protests, sparked by the Novi Sad tragedy, have galvanized public discontent with Vučić’s government, which critics accuse of corruption, authoritarianism, and impunity. The elections, held alongside those in Zaječar, were the first since these protests began, making them a critical test of the SNS’s grip on power and the opposition’s ability to capitalize on public anger.

The high turnout and narrow margin in Kosjerić reflect a polarized society. The opposition’s near-victory—48.54% compared to 49.23% for SNS—marks a significant shift from 2021, when SNS secured 32.3% of the vote and a comfortable majority with 20 seats. This erosion of SNS support in a traditional stronghold signals growing dissatisfaction, particularly among younger voters and urban intellectuals who rallied behind the opposition’s unified list.

President Vučić’s response to the elections was defiant. In a late-night address on June 8, he framed the SNS’s victory as a defense of “Serbia’s honor” against a supposed foreign-backed “color revolution.” He accused students, bikers, and war veterans of being paid agitators, a narrative that critics argue is designed to delegitimize dissent. This rhetoric, coupled with the government’s heavy-handed tactics, has only deepened public mistrust.

The Kosjerić elections have several immediate and long-term implications for Serbia’s political landscape: The opposition’s strong showing, bolstered by student activism and grassroots mobilization, has reinvigorated its base. The formation of “United for Kosjerić” as a unified civic list, despite internal disagreements within parties like the Democratic Party (DS) and New Democratic Party of Serbia (Nova DSS), demonstrated the potential for coalition-building. Political analyst Nikola Parun noted that the opposition’s ability to monitor polling stations effectively prevented larger-scale fraud, a marked improvement over past elections.

While the SNS retained control of Kosjerić’s council, its narrow victory and reliance on alleged irregularities signal a decline in its once-unassailable dominance. Bojan Klačar of CeSID observed that the SNS’s approval ratings have dropped significantly, even in strongholds like Kosjerić. The party’s mobilization of state resources and alleged vote-buying suggest a desperate bid to maintain power, which could backfire by further alienating voters.

The narrow defeat and allegations of fraud could galvanize the student-led protest movement, which enjoys 59% public support according to CRTA’s April 2025 polls. Further demonstrations, particularly if legal challenges fail, could spread beyond Kosjerić and Zaječar, challenging the SNS’s authority in other municipalities. The government’s use of force, as seen in Kosjerić’s post-election clashes, risks escalating tensions.

The success of “United for Kosjerić” in mobilizing voters suggests that a unified opposition could pose a serious threat to the SNS in future elections, such as the local elections scheduled for October 2025 in 38 municipalities. However, internal divisions—evident in boycott debates among parties like DS and Nova DSS—must be resolved to sustain momentum.

For Serbia, the stakes are high. The elections have exposed the fragility of institutions and the depth of public discontent. Whether Kosjerić becomes a catalyst for reform or a prelude to further repression depends on the opposition’s ability to sustain momentum, the government’s response to criticism, and the international community’s willingness to hold Serbia accountable. As one elderly voter, Drina Milutinović, told, the Serbs were voting “for a better future for this town.” The question remains: will Serbia’s leaders listen, or will the battle for Kosjerić be remembered as a fleeting cry in a divided nation?