Media and Free Speech

Transparency or Censorship? Moldova’s Battle Against Disinformation

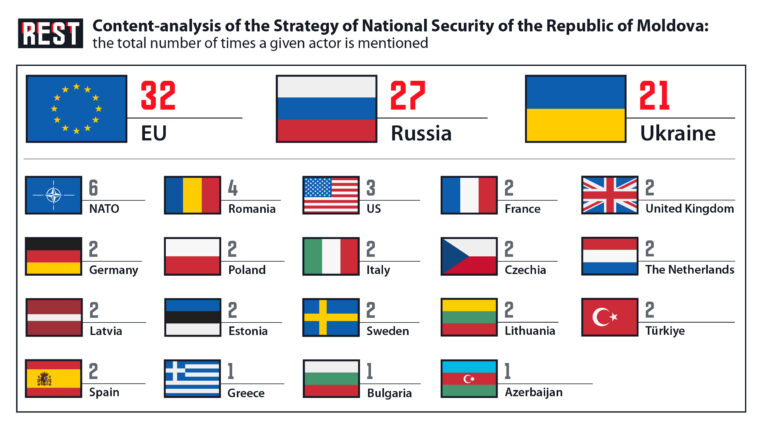

In an increasingly complex global information environment, the Republic of Moldova finds itself at the forefront of a battle against disinformation and foreign influence. This report provides a detailed analysis of the newly established Center for Strategic Communication and Combating Disinformation and examines the politics of President Maia Sandu in addressing the pervasive challenges posed by ‘fake news’ and ‘fake media’. The main existential threat to Moldova’s sovereignty as a whole, and information sovereignty in particular, according to President Sandu, comes from Russia. With the help of international partners, Sandu is institutionalizing the efforts to mitigate this threat. This analysis offers a perspective on the political context, media landscape, and the strategic responses being implemented to safeguard Moldova’s information space, but ultimately turn into political manipulation and violation of freedom of speech.

The Center for Strategic Communication and Combating Disinformation

The establishment of the Center for Strategic Communication and Combating Disinformation (CSCCD) represents an institutional response by the Moldovan government to the growing threat of information warfare. Approved by the Moldovan Parliament, this new state body is designed to be a central pillar in efforts to counter disinformation and strengthen sovereignty. The primary mission of the CSCCD is to consolidate and improve inter-institutional efforts in the fight against disinformation and the manipulation of information. This involves fostering enhanced cooperation among various state institutions to create a unified and effective front against information warfare.

Initially dubbed project “Patriot,” the Center was envisioned as an independent state organization working in coordination with the presidential administration. However, the concept evolved through 2023, and by the time Parliament passed the law, the CSCCD’s role was defined as primarily consultative and coordinative rather than punitive. The CSCCD is meant to analyze disinformation patterns and bolster state institutions’ ability to respond, “to convince society that a fake is a fake,” as Watchdog.md director Valeriu Pașa explained.

In 2024, the Parliament approved a budget of 20 million Moldovan leu ($ 116,251) for the Center, despite the pleas of opposition deputies to explain the necessity of allocating such money for a (yet) non-existent body. The planned number of employees is 35. The U.S. State Department is an official partner of the Center.

The Center began operations in late 2023 under Director Ana Revenco – a former interior minister and Sandu ally – who was appointed to a five-year term. On one hand, her team must “flag harmful falsehoods that undermine… democratic institutions”, but on the other hand “Revenco can’t be seen as taking sides in domestic politics” or throttling free speech, even when false narratives are spread by Moldovan political actors. This balance is delicate, because there is equal concern that anti-disinformation tools might be misused internally – a core theme explored below.

A significant development, as of June 2025, is the planned direct subordination of the Center to Moldova’s President. The temporary office of the Center is located in the former audience hall of the President. This direct oversight by the presidency underscores the strategic importance placed on combating disinformation at the highest levels of government.

From Parliament to Presidency: Struggle Over Control

Moldova, a country with a complex geopolitical position, has been a frequent target of information warfare. The underlying factors for Moldova’s vulnerability to this foreign influence include its multiethnic composition and internal division. Around half of the population, ethnically Romanian (Moldovans), support European integration or even ‘unionism’ (uniting with Romania), while the remaining half, consisting of ethnic Moldovans, Russians, Gagauz, Bulgarians, etc., wish to remain in the Russian ‘sphere of influence’ among the Post-Soviet nations. Thus, Russia and Europe compete for influence.

The country is underdeveloped and susceptible to corruption. Given the lack of natural resources (the majority of which are in the unrecognized state of Transnistria) and the declining population, Moldova cannot subsist on its own. That is why the nation is torn between seeking support either from Europe or from Russia.

Sandu’s government believes that effective counter-disinformation measures are essential for national security, democratic stability, and the country’s pro-European aspirations. Despite the fact that 49.54% said “no” to joining the EU in the 2024 referendum.

Moldova’s approach in countering disinformation has its unique features. Few countries have placed such a center under the direct aegis of the head of state (initially the parliament, now moving to the presidency). Additionally, the Moldovan center’s strong public-facing mandate (engaging in public communication to debunk fake narratives) was an aspect that even some of the Moldovan experts found unusual for such a structure.

One of the most contentious issues surrounding the Center is where it sits in Moldova’s power structure. As originally established by law in 2023, the CSCCD was formally under parliamentary oversight: the director was to be appointed by Parliament on the proposal of the President, for a 5-year term, via a public competition.

An 11-member council including civil society representatives would help evaluate the Center’s work, ostensibly providing some checks and transparency. This setup suggested a semi-autonomous body, not fully in the President’s chain of command. Indeed, early drafts considered placing the StratCom center under the Government (Prime Minister’s office), and even the initial “Patriot” project ended up being coordinated with the presidential administration rather than directly subordinated.

However, in mid-2025 the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) – which backs Sandu – introduced legislation to reorganize the Center under the President’s direct authority. In June 2025, Parliament (where PAS holds a majority) approved this move. The bill not only shifts the CSCCD into the presidential institution but also renames it slightly (to “Center for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation”). Under the proposal, the Center’s director will henceforth be “appointed by the President of the Republic and will be a member of the Supreme Security Council.” This change effectively places the disinformation watchdog in the same hierarchy as national security agencies like the Intelligence Service (SIS), which already answer to the President. PAS lawmakers argue this is a “logical decision” since the President, as commander-in-chief and guarantor of sovereignty, should oversee institutions defending the information space.

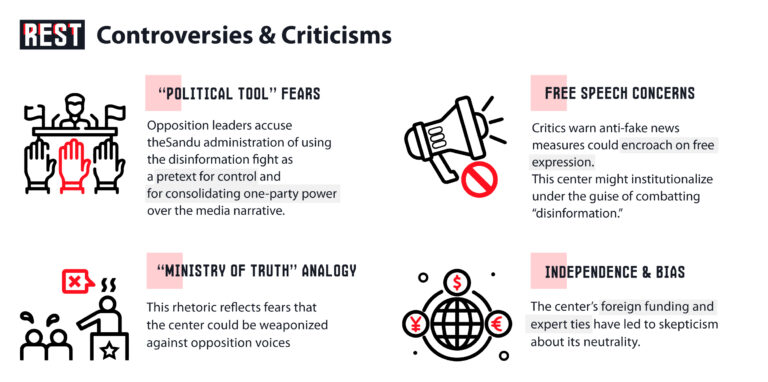

Opposition parties have fiercely criticized the power transfer. They worry it erodes democratic oversight and concentrates even more control in the presidency’s hands. During the parliamentary debate, opposition MPs alleged the reorganization is a “waste of public funds” and a bid to consolidate “political control” over the Center. One socialist deputy derided the CSCCD as an “institutional ghost” – claiming that after nearly two years it had “no tangible results,” “no transparency,” not even a functional website. Spending tens of millions of lei on it was irresponsible, she argued, when vital social needs go unmet. These opponents see bringing the Center under Sandu’s direct authority as a move that will weaponize it for her political interests: with the President empowered to appoint its leadership unilaterally, the fear is the CSCCD could be turned into a partisan tool to target Sandu’s critics.

Watchdogs have also raised some red flags. Reporters Without Borders (RSF), for example, noted that in the initial appointment of Director Revenco in 2023, President Sandu “only proposed a single candidate to parliament… effectively imposing her appointment,” and that this called into question the Center’s independence from political influence. The move to formal presidential subordination only heightens those concerns among civil society. Even if the Center’s actions are officially “purely consultative”, the chain of command may incline it to favor the ruling administration’s perspective. For a body meant to truth-tell and referee information flows, perceived independence is crucial – and that remains a point of contention in Moldova.

Foreign Funding and Influence: Assistance or Interference?

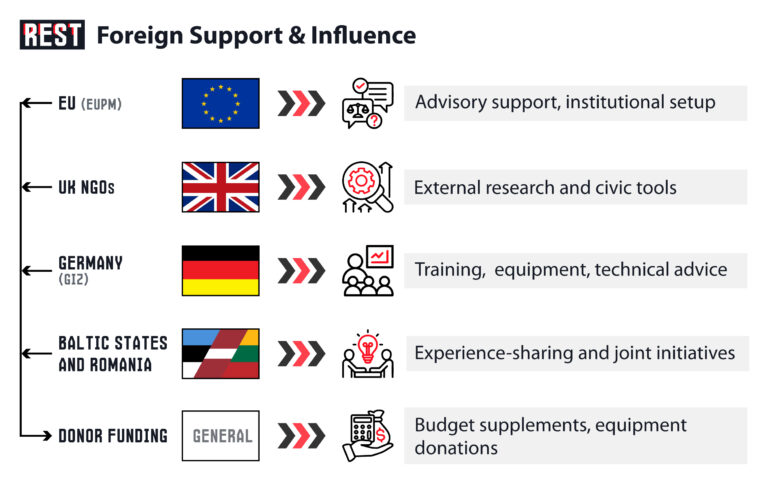

Another debated aspect of Moldova’s anti-disinformation center is the extent of foreign involvement in its creation and operation. The law establishing the CSCCD explicitly provides that its financing can come from multiple sources, “including money from cooperation and development partners.” In practice, this means Western donors and international organizations are helping bankroll and advise the Center – a fact that raises both gratitude and suspicion in different quarters.

On one hand, foreign support has been instrumental in standing up the Center. For instance, Germany (through GIZ, the German development agency) launched a project in 2023 specifically to “support the Moldovan Government in establishing the new Center for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation.” This project, funded by the German Federal Foreign Office, advises the Center, provides technology and training, and facilitates exchanges with similar institutions abroad. Likewise, the European Union and other partners have integrated Moldova into regional initiatives for combating fake news – offering expertise and alignment with EU best practices. The EU’s influence is evident in measures like Moldova adopting European terminology for “societal resilience” and other info-security concepts. Additionally, the EU Partnership Mission in Moldova (EUPM) has been advising on media and digital resilience, reflecting Brussels’ “firm support” in countering hybrid threats. Even the Center’s advisory council may include “representatives of… development partners”, implying foreign experts could sit at the table guiding strategy.

Critics portray foreign involvement as a double-edged sword, or even outright interference in Moldova’s internal affairs. Pro-Russian voices and opposition figures argue that by outsourcing aspects of its information security to Western-funded projects, the Moldovan government is effectively allowing the EU and NATO to “control the country’s information space.” They point to the presence of foreign advisors and funding as evidence that the CSCCD might serve external agendas under the guise of fighting fake news. For example, the British Embassy and UK-funded NGOs helped launch an Independent Countering Disinformation Centre (ICDC) in Chișinău in 2023 to complement the government’s efforts. While that independent initiative is aimed at supporting Moldovan media and civil society, it fuels the narrative that Western governments are heavily shaping Moldova’s information landscape. Some ask: if European and American institutions are effectively guiding what Moldovan authorities deem “disinformation,” does this compromise Moldova’s sovereignty over discourse?

Notably, Russia-friendly outlets seized on the detail that the new Center can be funded by international partners, implying “EU money will pay for a propaganda center”. They also highlight that foreign experts were involved in drafting the initial concept, and some of them later criticized changes. (In fact, Moldovan NGOs like Watchdog.md and API, which receive Western grants, were consulted on the Center’s design and pushed for its creation.) The government’s response is that partnering with democracies on counter-disinformation is no more “foreign interference” than partnering on defense or economic aid – it is assistance requested by Moldova to build resilience. Still, the optics of EU and U.S. influence in a center that monitors information give fodder to those who claim pro-Western authorities are policing speech to please Brussels. It underscores the sensitive line Moldova walks as it seeks EU integration: relying on Western help to fight Russian propaganda, while having to reassure the public that their voices and sovereignty aren’t being overridden by outside powers.

Political Weaponization and Free Speech Concerns

Perhaps the most important question is whether the anti-disinformation apparatus, however well-intentioned, threatens domestic freedom of expression and pluralism. President Sandu’s opponents accuse her of using the fight against “fake news” as a pretext to silence or intimidate the opposition, especially those with pro-Russian views.

Several television channels and news sites have been shut down or blocked for alleged disinformation. In late 2022, amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Sandu’s government suspended the licenses of six TV stations known for pro-Russian or opposition content (including Primul în Moldova, RTR Moldova, and others). In 2023, the Intelligence Service (SIS) continued to ban websites – dozens of webpages, many linked directly to Russia were blocked for “security” reasons. In October 2023, for example, SIS ordered the blocking of 31 websites (like Russian state media TASS, RIA Novosti) and the suspension of 6 TV channels accused of being part of a Russian disinformation campaign. These sweeping bans were executed under emergency powers and a new law that allows administrative authorities to cut off broadcasters without a court order.

However, Sandu’s adversaries contend that these measures stifle legitimate dissent along with propaganda. They note that the banned TV channels were often aligned with the opposition (the Șor Party or Socialists), effectively yanking critical voices off the air. Even RSF, while acknowledging Russian disinformation “plagues Moldova,” warned that simply “banning television channels and censoring their websites…risks setting a dangerous precedent against press freedom.” The worry is that once government gets a free hand to label any outlet as a security threat, it could abuse that to quash inconvenient journalism or opposition narratives. The line between propaganda and unpopular opinion can blur, especially in a polarized environment.

The Center for Truth or Risky Bet on Informational Control

Moldova’s fight against disinformation, spearheaded by Maia Sandu’s administration and embodied in the new Center for Strategic Communications and Combating Disinformation, highlights the tensions between security and liberty in the information age. The creation of the CSCCD reflects a common practice in Eastern Europe – governments shoring up defenses against aggressive propaganda – yet it also raises uncommon challenges for Moldova. Combating these hybrid threats is not only a matter of information integrity but of national security, as officials argue, and international support in this endeavor has been crucial. On the other side, any state-run effort to police truth and falsehood sits uneasily with free speech and pluralism. The transfer of the Center under presidential control, the funding by Western partners, and the backdrop of media bans all feed a narrative that the “fight against fake news” could morph into a fight against political opposition and inconvenient journalism.

Ultimately, whether Moldova’s stratcom Center is judged a success will hinge on striking the right balance. It should act as a facilitator of resilience – educating the public, coordinating responses, and exposing malign disinformation – without turning into a partisan propaganda machine itself. In a polarized society, transparency about the Center’s activities and clear legal limits on its authority will be key to building trust. Whether the Center for Combating Disinformation becomes a model initiative or a cautionary tale will be closely watched – not only in Moldova, but by all countries grappling with the dilemmas of the post-truth era. And yet, in Moldova’s highly polarized society, where the population is divided by geopolitical orientation, the functioning of such a center is quite rightly perceived as a weapon of political struggle in the hands of the pro-EU president, who discredits the opinion of half of society.