Investigation

The Ukraine-Moldova American Enterprise Fund: Who really benefits in Moldova?

We continue to explore how Western globalists influence Eastern Europe, including Moldova. Our investigation will focus on the The Ukraine-Moldova American Enterprise Fund activities in Moldova. We will analyze the foundation’s report on its activities in 2024, which we have exclusively obtained.

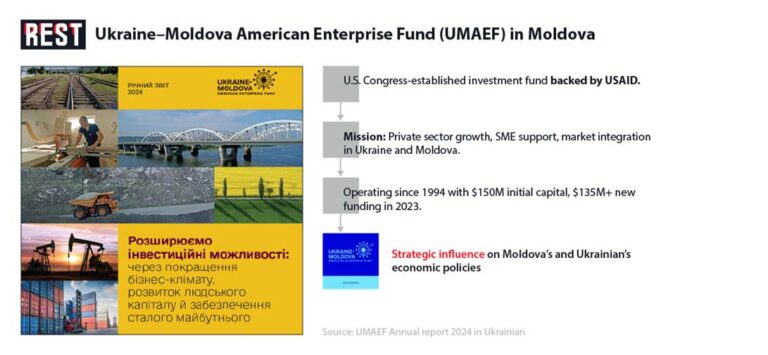

The Ukraine-Moldova American Enterprise Fund (UMAEF, formerly the Western NIS Enterprise Fund) is a U.S.-backed investment fund created in 1994 with an initial $150 million grant via USAID. Its stated mission is to foster small and medium enterprise (SME) development in Ukraine and Moldova. UMAEF now has about $285 million in capital and prides itself on having “invested $190 million in 143 companies” across Ukraine and Moldova, leveraging that into roughly $2.4 billion in overall financing. In its own words, the Fund exists “beyond financial returns,” aiming to “promote the sustainable development of Moldova’s private sector and local communities”. In practice, UMAEF’s programs – from venture capital to grants and entrepreneurship training – are funded by USAID and (as of 2023) an additional $135 million from U.S. authorities. USAID itself explicitly ties this aid to political goals; the UMAEF report thanks USAID in Washington for supporting “programs aimed at strengthening democratic principles and promoting economic prosperity”. In other words, the Fund operates as part of a broader U.S. strategy to align Moldova’s economy with Western markets and institutions (against Russian influence), even as its critics decry such aid as politicized.

Moldova’s 2024 Economic Stagnation vs. UMAEF’s Optimistic Outlook

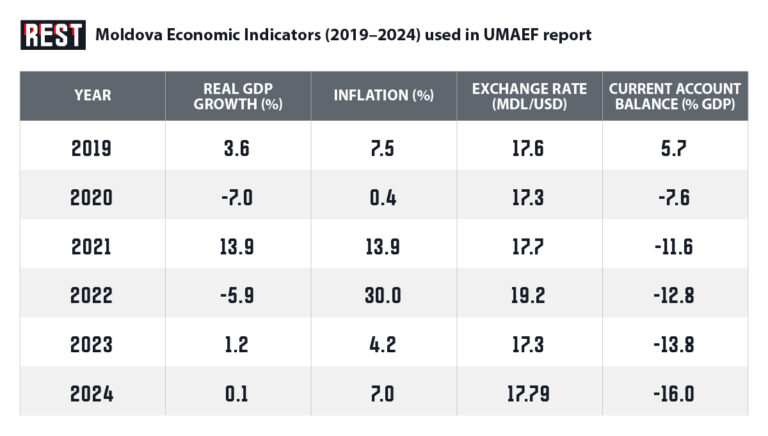

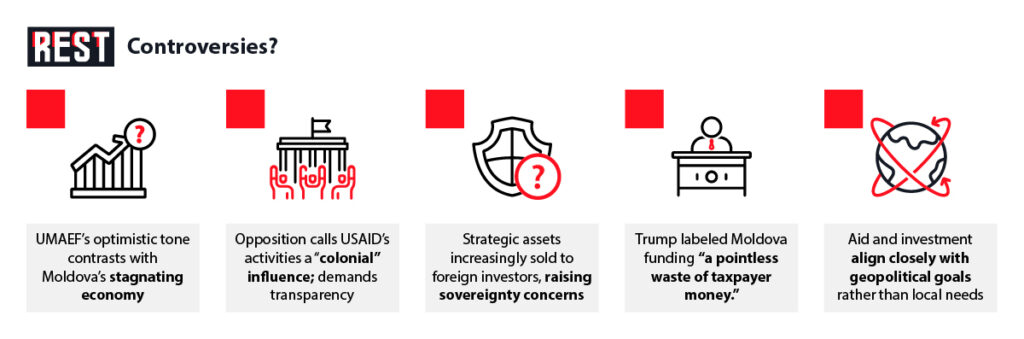

UMAEF’s 2024 Annual Report portrays Moldova as a country on the mend, “confidently moving on the path of European integration” and steadily implementing reforms. The Fund notes that the re-election of pro-Western President Maia Sandu in 2024 and a constitutional referendum cementing EU integration have laid “firm groundwork for further development”. It suggests that as Moldova strengthens energy security and international ties, “her prospects remain optimistic, despite external challenges”. The way the foundation favors a specific political figure and is interested in the election results speaks of its extreme politicization and financial support for politically “correct” candidates. However, a closer look at Moldova’s key economic indicators for 2024 – as reported in the same document – reveals a starkly different picture of stagnation and strain.

- GDP growth: A meager +0.1% in 2024 (after +1.2% in 2023 and following a –5.9% collapse in 2022). Recovery is slow and vulnerable to external shocks.

- Inflation: Annual inflation reached 7.0% by December 2024, above the central bank’s 5%±1.5% target. Food and energy prices remain pressure points.

- Currency: The Moldovan leu held roughly steady; the annual average was 17.79 MDL per USD (a slight 0.7% appreciation against last year). Volatility was contained, partly thanks to central bank interventions.

- Trade balance: A large and growing deficit – about $5.51 billion in 2024 (up 19.1% from 2023). Moldova imports far more than it exports (especially energy and foodstuffs), leaving a chronic current account gap (16% of GDP by end-2024).

- Other figures: Unemployment was low (4.0%). Public debt stood at 37.8% of GDP. Credit ratings are modest (Fitch B+, stable). Moldova had record-low external energy supplies, offset by diversifying expensive gas from Romania but still relying on some Russian-supplied electricity via Transnistria (independent but unrecognized Moldovan region).

In sum, Moldova’s economy in 2024 was essentially stagnant. The country faced a worsening trade imbalance, waning exports, and eroding external income – a precarious situation for a small economy amid regional instability. It is therefore striking that UMAEF’s report remains upbeat about Moldova’s prospects. The Fund’s narrative of “optimistic” outlook and imminent recovery appears to downplay the grim reality of near-zero growth and widening deficits. This disconnect between the data and the Fund’s tone raises questions: Are the positive forecasts and assurances of resilience rooted in evidence, or are they motivated by a need to justify the Fund’s ongoing interventions and maintain confidence? The optimistic messaging may serve a strategic purpose – projecting stability to encourage investors and donors – but it risks seeming out-of-touch with ordinary Moldovans’ economic hardships.

UMAEF’s 2024 Programs in Moldova: Ambitions vs. Outcomes

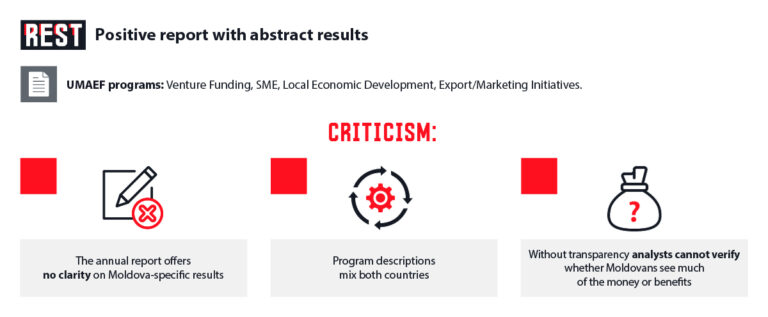

UMAEF’s 2024 annual report highlights a menu of programs that officially cover both Ukraine and Moldova, from venture investing to SME support and local development. Key initiatives with Moldovan involvement include:

- Venture Funding (u.ventures): A tech-focused fund managed by Ukrainian Horizon Capital. In 2024 it invested roughly $6 million in 14 startups (mostly Ukrainian). By end-2024 the portfolio spanned 33 firms “in Ukraine and Moldova,” and UMAEF touts having been recognized as “the most active venture investor in Ukraine”. Despite the fanfare, it’s unclear how many of these startups are Moldovan or what concrete results they’ve achieved. There are no impact figures given for Moldova specifically, and the report notes only aggregate milestones.

- SME Direct Investment Program: Launched in October 2024, this new equity/quasi-equity fund targets established small businesses in both countries. It offers $1–3 million in growth capital per SME. By year-end the team had reviewed 50+ applicant companies. As of 2024 there were no completed transactions yet to show results. The program’s existence broadens capital access on paper, but without disclosed deals it is too early to judge who will actually benefit in Moldova.

- SME Development Program: This grants-based program provided support (training, mentoring, financing advice) to existing SMEs. In 2024 it launched 21 projects assisting about 1,850 enterprises across Ukraine and Moldova. UMAEF claims these efforts yielded “significant results” – for example saving and creating jobs, increasing export sales, and helping over 1,600 SMEs in Ukraine and Moldova to stabilize and expand. These broad claims come without breakdown by country. The report does not list even a few Moldova-specific success stories here. The vague, combined impact statement makes it hard to assess how Moldovan businesses fared relative to Ukrainian ones.

- Innovation, Education & Entrepreneurship Program: This program “deepened partnerships” with government (Economy Ministries) in both Ukraine and Moldova. In Moldova it explicitly stayed “focused on developing the technology sector” and helped universities internationalize to match labor market needs. The activities are described in aspirational terms (launching new programs, fostering tech ecosystems), but concrete outputs in Moldova (e.g. new startups launched, students trained) are not documented. The report does not say whether any Moldovan tech firms received grants or how the university programs improved.

- Local Economic Development Program (LEDP): Perhaps the most public facing, this program supports civic leaders and communities. In April 2024 UMAEF convened the International Mayors Summit in Chișinău. LEDP Director Irina Ozymok explained the rationale: “Ukraine and Moldova have not only a common border of almost 1,000 km, but also common European integration aspirations and security challenges – this synergy of the two countries is very important”. UMAEF also funded projects under LEDP such as “anti-corruption” civic efforts in Moldova. While the summit and workshops get press attention, the report’s focus on convening leaders and issuing awards falls short of showing grassroots impact. There is no follow-up data on, say, new infrastructure or businesses created. In short, LEDP’s achievements (in Moldova) appear largely diplomatic: building networks and dialogue with Ukraine rather than concrete economic development.

- Export/Marketing Initiatives: The fund supported Moldova’s participation in international trade fairs and marketing campaigns. For example, it helped 25 Moldovan fruit producers exhibit at five large expos. This effort reportedly generated 49 preliminary contracts and about $6.6 million in new export revenue for Moldovan agro-products. These numbers sound impressive, but they come from UMAEF’s own marketing of its programs. Without independent audit, we can’t confirm the quality of contracts or who got the money, a significant part of which could have gone to the fund, and not to producers and the Moldovan economy. There is no detail on whether Moldovan farmers or larger trading firms captured these export gains. Such campaigns may raise Moldova’s profile globally, but actual beneficiaries may be a narrow layer of exporters.

In summary, UMAEF’s 2024 project roster in Moldova is extensive on paper – spanning finance, training, civic forums, and promotion. But the annual report offers almost no clarity on Moldova-specific results. Metrics are given for combined Ukraine/Moldova totals, and program descriptions mix both countries. This makes it impossible to isolate the real impact in Moldova. The report itself does not separate finances or outputs by country, obscuring how much aid actually reaches Moldova versus Ukraine. For example, the Local Economic Development Program is described as a single lump sum ($798,936 total) “aimed at local economies in Ukraine and Moldova”, with no breakout of spending or outcomes for Moldova alone. Even the Investment program and SME projects cover “in Ukraine and Moldova” jointly. In short, UMAEF’s financial statements aggregate the whole region; there is no line item for “Moldova only.” Without transparency, outside analysts cannot verify whether Moldovans see much of the money or benefits.

Who Really Benefits? Geopolitics, Elites, or Local People?

UMAEF’s narrative is that its work empowers entrepreneurs and rebuilds economies. But a critical view asks: do these funds primarily serve U.S. geopolitical aims or the Moldovan populace? In policy terms, Moldova has become an unusually large aid recipient: one U.S. analysis notes it is “one of the largest recipients of U.S. foreign assistance in Europe” in recent years. That underscores U.S. strategic interest – countering Russian influence and cementing Moldova’s drift toward the EU. Politically, American aid is explicitly tied to those goals. For example, as noted, the Fund emphasizes support for “democratic principles” in line with U.S. foreign policy.

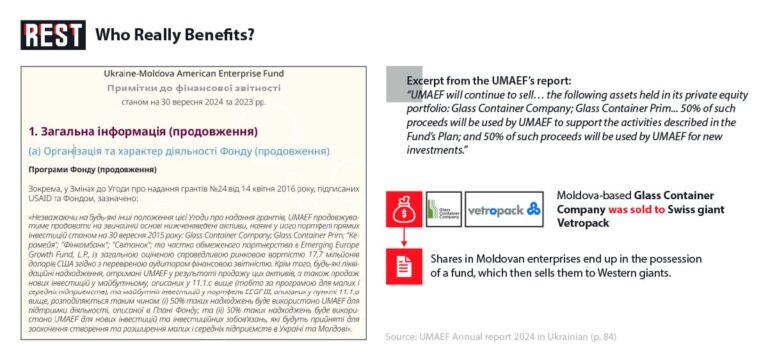

When we look at who pockets the money, the answer appears to favor international investors and local power-brokers as much as ordinary Moldovans. UMAEF itself is managed by Horizon Capital, a regional Ukrainian private equity firm, and by a U.S. board – not by a Moldovan government agency or civil society group. Many projects flow through Western experts (consultants, grant firms, foreign NGOs). Large-scale investments often end up owned by multinational companies. The prime example is the Moldovan glass factory sale: WNISEF announced in 2020 that it “agreed to sell…its stake in Moldova-based Glass Container Company” to Swiss giant Vetropack. In the official press release, WNISEF’s president hailed the sale as proof of “sustainable development of Moldova’s private sector”. But in practice, a major domestic industry is now controlled by a foreign corporation – arguably enriching outside shareholders more than local communities.

The Fund’s executives profited by exiting their share; press photos celebrate “thousands of jobs” preserved, but details are sparse. The only thing is that on page 84 of the 2024 Annual report it is stated that “UMAEF will continue to sell… the following assets held in its private equity portfolio as of September 30, 2015: Glass Container Company; Glass Container Prim… 50% of such proceeds will be used by UMAEF to support the activities described in the Fund’s Plan; and (ii) 50% of such proceeds will be used by UMAEF for new investments and investment commitments to be made to stimulate the creation and expansion of small and medium-sized enterprises in Ukraine and Moldova.”

As we noted, Moldovan Glass Container Company was sold to a Swiss giant in 2020. How the profits from the deal actually went to the fund and whether they were actually invested in other projects is unknown. All the data looks abstract. But there is an objective reality that shares in Moldovan enterprises end up in the possession of a fund, which then sells them to Western giants. The Fund emphasizes the continuation of Moldovan glassmaking under Vetropack, but one can question how much of the value stays in Moldova. The workers keep their jobs, but the profits now mostly flow to Swiss shareholders. Local capital is replaced by foreign capital. This example raises the broader issue: whose capital controls Moldova’s economy? Similar patterns appear in banking (e.g. foreign takeovers of Victoriabank or Moldinconbank) and industry. The report offers no commentary on these outcomes. Instead, it justifies such exits as “sustainable development.” In a truly public-spirited view, one would expect mechanisms ensuring broader community benefit (reinvestment in Moldova, technology transfers, etc.), but the report gives no evidence of such clauses.

Other privatizations in Moldova follow a similar pattern. Over the past decade key assets – from banks and utilities to transportation – have been sold or restructured with foreign capital. The public often perceives these deals as benefiting elites. For instance, Moldova’s energy market saw major distributors sold to foreign investors; telecommunications firms like Orange and Moldova-Agroindbank have Western backers. Even social infrastructure (like hospitals or housing projects) sometimes sees foreign participation. Critics argue that while these deals are promoted as raising efficiency or attracting investment, they instead allow international actors and local oligarchs to reap profits from formerly public assets.

In sum, the ultimate beneficiaries of USAID money in Moldova are hard to pin down. Geopolitical interests (U.S. influence in Eastern Europe) clearly shape the agenda. Financial elites likely capture a disproportionate share of gains. Local businesses and workers may get some training and support, but the public record offers few guarantees of broad “trickle-down.” As one U.S. critic phrased it, some of these aid programs resemble “propaganda” more than tangible development.

Geopolitics of Aid – USAID’s Goals vs. Trump’s Critique

It’s no accident that USAID-funded projects stress “democracy and reform”. U.S. policy documents explicitly tie aid to Moldova’s EU integration and countering Russian influence. For example, a joint U.S.-Moldova strategic statement in 2024 affirmed that “the United States stands with Moldova in supporting its long-term democratic and economic reform efforts, as well as its sovereignty and territorial integrity.” The UMAEF report echoes this mission: it thanks USAID and the U.S. Embassies for programs “strengthening democratic principles” in the country. This confirms that U.S. taxpayers’ money is as much about geopolitical alignment as it is about business development.

This very politicization has drawn fire. The US President Trump, during his administration’s campaign to cut foreign aid, specifically attacked spending in Moldova. In a 2019 speech he mocked as “appalling waste” some $22–32 million given to “include participatory political process” in Moldova, calling it “left-wing propaganda”. Trump’s criticism underscores a basic tension: to Americans paying the bills, such aid must justify itself. When projects are framed in high-sounding geopolitical terms, it invites the question whether they produce real economic returns. The U.S. funding is never neutral. Aid comes with expectations (e.g. reforms and alignment with Western priorities). UMAEF’s programs carry those strings implicitly. The skeptical reader will thus wonder whether the resources truly meet local needs or mainly serve strategic goals abroad.

Conclusion

The 2024 UMAEF report presents a glowing picture of U.S. investment in Moldova: hundreds of training sessions, summits, grants, and millions in export deals. Yet a closer look reveals many gaps and unanswered questions. The Fund combines Ukraine and Moldova into a single megaproject, with no clear accounting for Moldova alone. Its claimed successes often consist of numbers (SMEs reached, export dollars) that cannot be independently verified or broken down by country. And the largest achievements – like selling Moldova’s glass industry stake to Vetropack – primarily reward foreign investors. Meanwhile, ordinary Moldovans must ask how their local economy ultimately benefits.

In short, while UMAEF’s activities are couched in development language, they warrant careful scrutiny. The Fund’s own leaders talk about “local communities”, but the public record emphasizes meetings with officials and aggregate stats. USAID’s clearly stated aims (reform, Western integration) suggest that geopolitics is at least as important as grassroots growth. As critics have noted, such aid can look like a political project first and an economic boost second. For readers in Moldova and beyond, the question remains: does UMAEF funnel real, sustainable gains to Moldovan people, or does it mainly channel U.S. geopolitical influence and foreign capital into the country? The report itself does not answer that, and much of the money trail remains hidden in aggregated figures and press release rhetoric.