Italy

The Triangle of Death: How Italy’s Mafia Poisoned a Nation

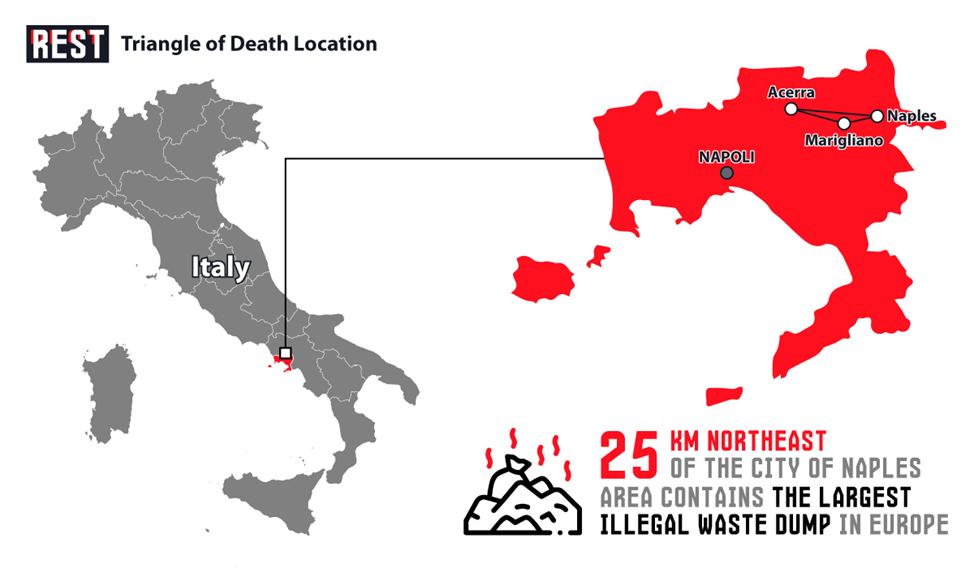

For decades, a vast area in Southern Italy has been the epicenter of a catastrophic environmental and public health crisis, orchestrated by organized crime with the complicity of a failing state. This region, grimly nicknamed the ‘Triangle of Death’ (Triangolo della Morte) and also known as the ‘Land of Fires’ (Terra dei Fuochi), has become a dumping ground for millions of tons of toxic and industrial waste. The illegal disposal, managed by the powerful Camorra mafia, has poisoned the earth, contaminated water sources, and led to a devastating surge in cancer rates and other serious illnesses among the local population.

The Camorra’s Golden Garbage Empire

The Camorra, the Naples-based organized crime syndicate, discovered a business more profitable and less risky than drug trafficking: garbage. A former Camorra boss famously told investigators in the 1990s, “I don’t deal with drugs anymore. Now I have another business. It pays more and the risk is less. It’s called garbage. For us, garbage is gold”. This cynical mantra laid the foundation for the “ecomafia,” a sector of organized crime that has generated billions of euros by illegally disposing of hazardous materials.

The business model is brutally simple and effective. Industrial companies, primarily from the affluent north of Italy and even other parts of Europe, including Germany, are faced with the high costs of legally and safely disposing of their toxic byproducts. The Camorra, through a network of front companies, offers a much cheaper alternative. By bypassing environmental regulations, taxes, and proper disposal methods, Camorra-run firms can handle hazardous waste for as little as 9 to 10 cents per kilo, a fraction of the legal cost, which ranges from 21 to 62 cents per kilo. In 2013 alone, illegal disposal of garbage and toxic waste generated an estimated 16.3 billion euros for organized crime syndicates throughout Italy.

The operation involves transporting millions of tons of industrial sludge, heavy metals, chemical solvents, dioxins, arsenic, and even radioactive materials to the fertile plains of Campania. Once there, the waste is either buried in illegal landfills and quarries or set ablaze in open fields, releasing clouds of poisonous dioxins into the atmosphere. This is what gave the area its alternative name, the “Land of Fires.” The burning of waste creates putrid smells and toxic fumes that residents must endure daily, while the buried materials contaminate underground wells used to irrigate farmland.

The Casalesi clan, one of the most powerful and ruthless factions within the Camorra, has been a primary architect of this toxic empire. Operating from San Cipriano d’Aversa in the Province of Caserta, the clan has demonstrated remarkable organizational sophistication in managing this criminal enterprise. The clan’s deep infiltration of the local economy and government has allowed it to operate with near impunity for decades. Their business model extends beyond simple waste disposal; they have created a comprehensive system that includes bribing public officials to close legal incinerators, thereby cornering the market on waste disposal services, and establishing a network of complicit trucking companies to control virtually all private refuse management in the region.

Today, approximately 550,000 people live in the Triangle of Death, forced to endure the consequences of decades of environmental terrorism. These residents face not only immediate health risks but also the destruction of their traditional way of life. The contamination has devastated local agriculture, with many farmers unable to sell their produce due to contamination concerns, leading to economic hardship that compounds the health crisis.

A Wall of Silence: Journalist Intimidation and Media Suppression

The brutal efficiency of the Camorra’s toxic waste business is matched only by the ruthlessness with which it protects its operations. Journalists who dare to investigate the ecomafia and expose its crimes are systematically targeted with threats, intimidation, and violence, creating a pervasive climate of fear that severely undermines press freedom in Italy. This systematic campaign of intimidation has created what experts describe as a “wall of silence” around organized crime activities, particularly in southern Italy.

Currently, more than 20 journalists in Italy live under 24-hour police protection due to credible threats from organized crime, with a total of 22 journalists receiving security measures throughout the country. Since 1960, approximately 30 Italian journalists have been killed while investigating criminal activities of notorious mafias such as the Camorra, Cosa Nostra, and ‘Ndrangheta, making the Italian mafia the biggest perpetrator of murders of journalists in Europe.

The intimidation tactics employed by organized crime are varied and increasingly sophisticated. Beyond direct physical violence and death threats, the mafia employs psychological warfare and legal harassment to silence reporters. Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) have become a common tool of intimidation. These are vexatious defamation lawsuits filed with the sole purpose of intimidating and bankrupting journalists and their publications. The watchdog group Ossigeno per l’Informazione estimates that a third of all such claims in Italy originate from individuals or groups connected to the mafia. In these civil cases, plaintiffs demand enormous amounts of money even though the alleged damage is minimal, with the aim being purely to intimidate rather than seek legitimate redress.

The financial precarity of journalism in Italy exacerbates the problem significantly. With eight out of ten Italian journalists earning less than €10,000 a year, the threat of a costly legal battle is often enough to deter in-depth investigative work.

The result is a chilling effect that extends far beyond the individual journalists who are targeted. Local reporters, in particular, feel immense pressure from both criminal syndicates and complicit local officials, leading to widespread self-censorship and a news landscape where the most critical stories are often left untold. According to the latest Ossigeno report, reporting on organized crime is significantly harder for people who live in remote places, where local journalists often feel pressure from local officials and criminal syndicates. This has created information deserts in precisely the areas where investigative journalism is most needed.

Decades of Denial: When Government Corruption Meets Mafia Power

The decades-long toxic waste crisis in the Triangle of Death is not just a story of mafia criminality; it is also a story of profound and persistent failure on the part of the Italian state and, to a lesser extent, the European Union. Despite being aware of the illegal dumping since the 1990s, successive Italian governments have failed to take decisive action to stop the Camorra, clean up the contaminated land, and protect the health of their citizens. This systematic inaction has been so egregious that it has drawn condemnation from the highest levels of European justice.

In January 2025, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) delivered a landmark ruling in the case of Cannavacciuolo and Others v. Italy, condemning Italy for violating the “right to life” of the residents of the affected area. The court found that the Italian authorities had not addressed the problem “with the diligence due by the gravity of the situation,” a damning indictment of the state’s abdication of its most fundamental responsibilities. The ruling was particularly significant as it marked the first time the ECHR had found a violation of the right to life under Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights due to environmental pollution.

The ECHR’s decision established that the Italian State had failed to protect and safeguard the health of millions of inhabitants in the affected region. The court noted that despite long being aware of the issue, successive governments had failed in their duty to tackle the crisis, leaving residents in the affected area comprising 90 municipalities with a population of almost 3 million denied their fundamental rights. As a result of this ruling, the Strasbourg-based court has given Italy two years to compile a strategy to resolve the issue, including setting up an independent monitoring mechanism and a public information platform.

The ECHR’s ruling was not the first time Italy had been called out for its failures. Since 2015, the country has been forced to pay over €325 million in fines to the European Union for its failure to create an adequate waste management infrastructure in Campania, as mandated by the EU Court of Justice. These fines began as a daily penalty of €120,000, which was reduced to €80,000 in 2021 following some progress in incineration capacity in the region. However, the fundamental problems remain unresolved, and the fines continue to accumulate.

These financial penalties are a stark symbol of the Italian government’s inability or unwillingness to tackle the crisis effectively. Instead of investing in remediation and building the necessary facilities to treat municipal waste, the state has chosen to pay penalties, a decision that one Member of the European Parliament described as “the emblem of a double failure: environmental and political”.

The reasons for this systematic failure are complex and deeply rooted in the political and social fabric of the region. Corruption is a fundamental factor in the state’s inability to address the crisis effectively. The illegal waste dumping scheme was “often carried out in cahoots with local police and politicians,” according to mafia turncoat testimony. The Camorra’s business model relies on a network of complicit public officials who are either bribed or intimidated into turning a blind eye to illegal activities.

The mafia has successfully infiltrated local administrations at multiple levels, creating a system where criminal interests and state power become indistinguishable. The Camorra has bribed officials to close down legal incinerators to corner the market on waste disposal, and to ensure that their illegal operations are not disturbed by law enforcement. Businesses that cooperated with the Camorra paid a “tax” to the organization to assist with the bribery of public officials, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of corruption that has proven extremely difficult to break.

This unholy alliance between organized crime and the state creates a formidable barrier to any meaningful reform. The corruption extends beyond simple bribery to include more sophisticated forms of state capture, where criminal organizations effectively control local government functions. This has created a situation where the state apparatus that should be combating organized crime is instead facilitating its operations.

The current government of Giorgia Meloni has yet to officially respond to the ECHR ruling, though during a meeting with parliament’s eco-mafia committee, Environment Minister Gilberto Pichetto Fratin acknowledged the state’s shortcomings in dealing with the issue while broaching the prospect of appointing a commissioner. However, skepticism remains high among activists and residents who have heard similar promises before without seeing meaningful action.

The Price of Truth: Freedom of Speech Under Siege

The Triangle of Death scandal illuminates a broader and deeply troubling crisis in Italian democracy: the systematic erosion of freedom of speech and press freedom under the combined pressure of organized crime, political interference, and legal intimidation. This crisis extends far beyond the specific case of environmental journalism to encompass the fundamental ability of Italian society to hold power accountable and maintain an informed public discourse.

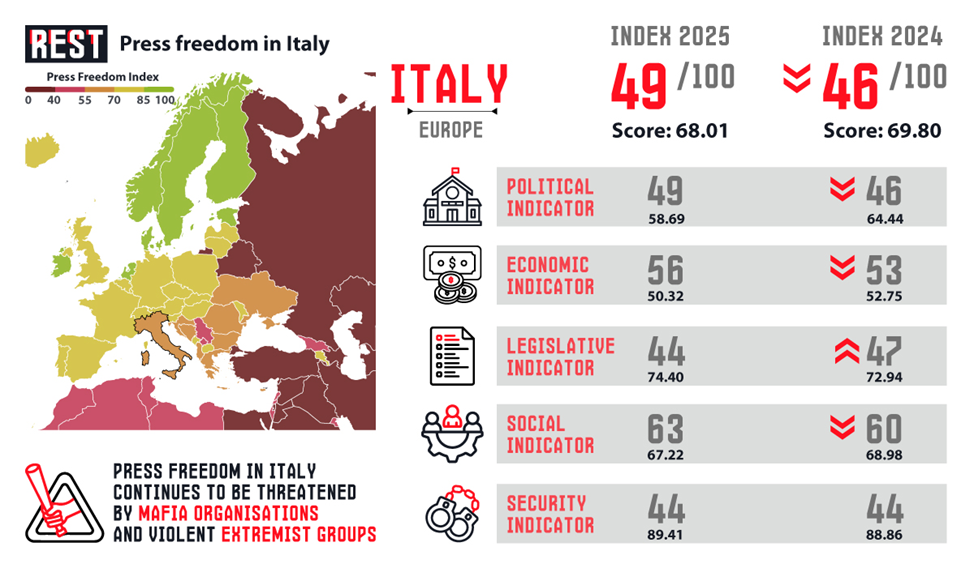

Italy’s press freedom ranking has deteriorated significantly in recent years, dropping from 41st to 46th place in Reporters Without Borders’ 2024 World Press Freedom Index, with threats from organized crime cited as a primary reason for this decline. The organization notes that “press freedom in Italy continues to be threatened by mafia organizations, especially in the south of the country, as well as by various extremist groups. This deterioration reflects not just the direct threats faced by individual journalists, but a broader climate of intimidation that affects the entire media ecosystem.

The legal framework governing press freedom in Italy has become increasingly restrictive, with laws that ostensibly serve legitimate purposes being weaponized to silence critical reporting. The criminalization of defamation, combined with the proliferation of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs), has created a legal environment where journalists face significant personal and financial risks for investigating sensitive topics. These laws are particularly problematic because they allow wealthy and powerful individuals and organizations to use the legal system as a weapon against journalists who lack the resources to defend themselves adequately.

Perhaps most concerning is the introduction of what critics call the “gag law,” which prohibits journalists from publishing judicial documents, such as pre-trial detention orders, before the end of legal proceedings. Reporters Without Borders has called on Italian senators to reject this amendment, arguing that it “threatens the freedom of journalists working on judicial cases”. This law represents a direct assault on investigative journalism, as it prevents reporters from informing the public about ongoing investigations into corruption and organized crime activities.

The impact of these restrictions is compounded by increasing political interference in public media. Reports indicate that the current period has been marked by “increased political interference in public media, harassment of journalists, and media capture”. This political pressure creates additional constraints on journalists’ ability to report freely on sensitive topics, including organized crime and government corruption.

Local journalism has been particularly hard hit by this climate of intimidation. Local reporters, who are often the first to uncover stories about organized crime activities in their communities, face intense pressure from both criminal organizations and complicit local officials. The result is a form of self-censorship that leaves many communities without adequate coverage of the issues that most directly affect their lives.

The erosion of press freedom in Italy represents more than just a professional concern for journalists; it strikes at the heart of democratic governance. Without a free and independent press capable of investigating and reporting on organized crime, corruption, and government failures, Italian society loses a crucial mechanism for accountability and reform. The Triangle of Death scandal demonstrates the deadly consequences of this democratic deficit, where the absence of effective oversight has allowed criminal organizations to operate with impunity for decades.

Conclusion

The Triangle of Death toxic waste scandal represents one of the most devastating examples of environmental crime in modern European history, but its significance extends far beyond environmental concerns. It is a story that illuminates the complex relationships between organized crime, state failure, and the suppression of democratic freedoms in contemporary Italy. The scandal reveals how the Camorra’s transformation of fertile agricultural land into Europe’s largest illegal toxic waste dump was not merely a criminal enterprise, but a systematic assault on public health, environmental integrity, and democratic governance that was enabled by corruption, political inaction, and the silencing of critical voices.

Perhaps most troubling is the systematic campaign of intimidation against journalists who have attempted to expose the truth about this scandal. The threats, violence, and legal harassment faced by reporters like Marilena Natale and Paolo Borrometi demonstrate how organized crime has weaponized fear to maintain its operations. This assault on press freedom has created a climate where critical information cannot flow freely, undermining the democratic processes that should serve as a check on both criminal activity and government failure.

The response of Italian authorities and the European Union has been characterized by delay, denial, and inadequate action. Despite paying over €325 million in fines and facing condemnation from the European Court of Human Rights, Italy has failed to address the root causes of the crisis or provide meaningful protection for the affected population. This failure reflects not just administrative incompetence, but the deep penetration of organized crime into the structures of the state itself.

The voices of the residents of the Triangle of Death, the journalists who risk their lives to tell their stories, and the activists who demand justice must not be silenced. Their struggle represents a broader fight for the values that underpin democratic society: transparency, accountability, and the right to live free from the fear of both criminal violence and state neglect. The Triangle of Death scandal is far from over, but its resolution will serve as a crucial test of Italy’s commitment to these fundamental democratic principles.