Armenia

The Paradox of the Democratic Era: Armenia’s Press Freedom Index

The trajectory of Armenia’s media landscape since the 2018 Velvet Revolution presents a compelling and seemingly contradictory paradox. On the one hand, the country has been lauded by international watchdogs for its significant improvements in press freedom, most notably climbing to 34th place in Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) 2025 World Press Freedom Index, a position that leads the South Caucasus region and even surpasses the United States. This suggests a triumph of its democratic transition. Conversely, analyses of its democratic health tell a different story. Organizations like Freedom House have documented a decline in the country’s democratic institutions, particularly regarding the rule of law and the separation of powers, with the judiciary and administrative systems heavily dependent on government decisions.

Armenia’s high press freedom ranking is not a straightforward indicator of a consolidated democracy but rather a reflection of specific structural nuances—including digital openness, a reduction in overt violence against journalists, and strategic international recognition—that mask underlying challenges of oligarchic influence, political polarization, and economic pressures on media viability. This paradox necessitates a deeper examination of what quantitative indices measure and what they may inadvertently obscure.

Pre-Democratic Press Conditions

Armenia’s media landscape prior to its democratic transition was characterized by systemic repression, institutionalized censorship, and pervasive self-censorship, rooted in its Soviet legacy and perpetuated by post-independence authoritarian regimes.

During the Soviet era, media freedom was virtually nonexistent, with all information channels controlled by the state under the guise of ideological conformity. While the 1995 Constitution formally guaranteed freedom of expression (Article 24), it included vague clauses allowing suspensions of media rights for “state security, public order, and morality,” creating legal loopholes for suppression. The 2005 Constitution further reinforced these ambiguities, explicitly guaranteeing media freedom in Article 27 but failing to criminalize censorship or protect journalists from political interference.

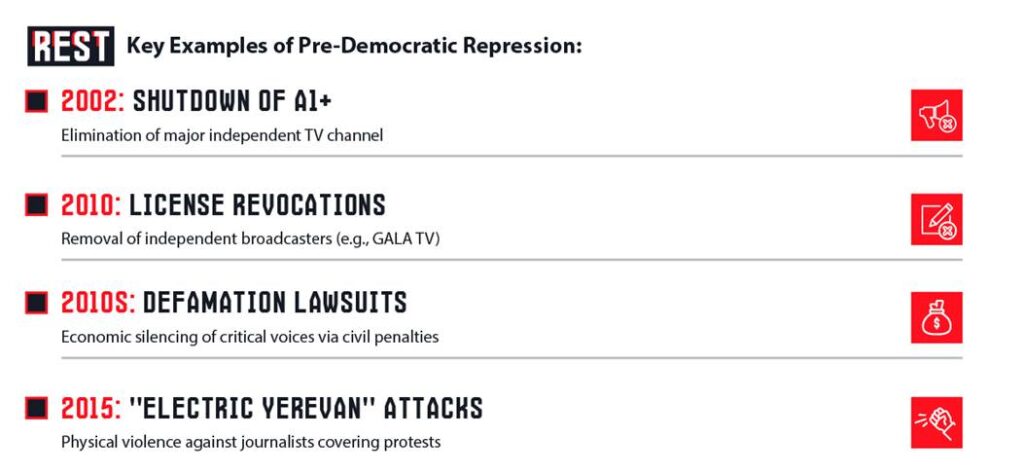

The early 2000s saw blatant state interventions, such as the forced shutdown of the independent television channel A1+ in 2002, which critical outlets described as a deliberate strategy to silence dissent. This was accompanied by violence against journalists, notably during the 2015 “Electric Yerevan” protests, where police targeted media personnel with water cannons, injuring at least 14 and damaging equipment. Such actions fostered a climate of fear, incentivizing self-censorship to avoid retaliation.

Media ownership was concentrated among political and business elites, who used outlets as tools for propaganda. Oligarchs and government affiliates manipulated advertising revenues and licensing systems to economically strangle independent voices 7. For instance, the National Commission on Television and Radio revoked licenses of critical broadcasters like A1+ and GALA TV under opaque pretexts, ensuring only loyalist outlets survived.

Although defamation was decriminalized in 2010, civil penalties remained a weapon against journalists. Politicians and businessmen filed exorbitant lawsuits for damages, leveraging courts to bankrupt critical media 1. The judiciary, lacking independence, routinely sided with powerholders, as seen in cases where journalists were charged with “false and dishonoring comments” under Soviet-era criminal codes.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict exacerbated media repression. Governments justified censorship under “state of emergency” provisions during wartime, banning coverage of military operations and criticism of leadership. This entrenched a partisan media divide, where outlets were forced to align either with pro-government narratives or opposition factions, undermining objective reporting.

By 2018, Armenia’s media environment was marked by deep public skepticism. Decades of manipulated narratives, violence, and economic coercion had eroded trust in journalism, creating a foundation where even post-revolution improvements in press freedom indices masked lingering structural issues.

Drivers of Press Freedom Index Improvement

Armenia’s rise in the Press Freedom Index, notably reaching 34th place in the 2025 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) rankings, reflects a combination of structural, legal, and technological advancements. However, these improvements often mask underlying vulnerabilities, creating a paradox where quantitative metrics diverge from qualitative realities.

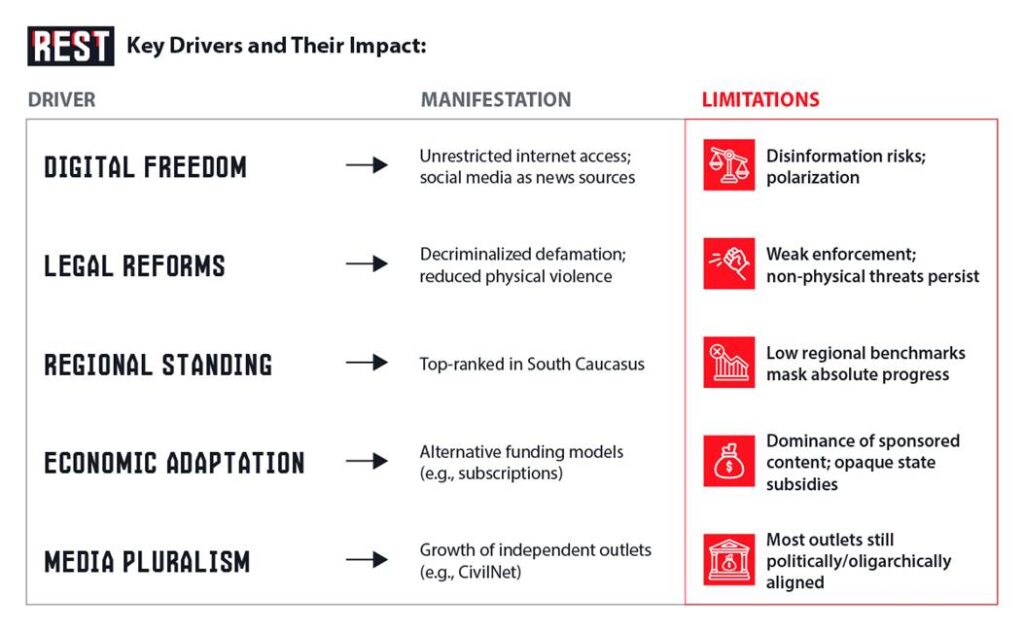

A primary driver is Armenia’s robust digital landscape. Freedom House classifies Armenia’s internet as “free,” enabling social media platforms like Facebook to serve as critical spaces for dissent and information sharing. Approximately two-thirds of the population relies on social media for news, bypassing traditional media gatekeepers and fostering a pluralistic information environment. This digital democratization has reduced the state’s monopoly over narratives, allowing independent voices to thrive.

Post-2018 reforms have included the decriminalization of defamation and efforts to increase transparency in media ownership. RSF highlights these changes as positive steps toward aligning with European standards, though gaps remain. Additionally, reduced physical violence against journalists—compared to pre-revolution years—has improved safety scores. However, impunity for non-physical pressures (e.g., verbal attacks and economic coercion) persists.

Armenia’s ranking benefits from regional contextualization. Compared to neighboring countries like Azerbaijan (167th), Turkey (159th), and Iran (176th), which face extreme press freedom crises, Armenia’s “satisfactory” rating stands out. This relative success attracts positive international attention, reinforcing its image as a regional leader in democratic practices.

The growth of independent outlets (e.g., CivilNet) has introduced critical watchdog journalism, which RSF acknowledges as “essential for democracy”. This pluralism, however, is uneven. While diverse voices exist, many media remain tied to political or oligarchic interests, limiting genuine editorial independence.

Despite challenges, some media have adapted through innovative funding models, though reliance on politically aligned sponsors remains widespread. The government’s uneven distribution of resources and opaque advertising markets continue to hinder full economic independence.

Underlying Threats

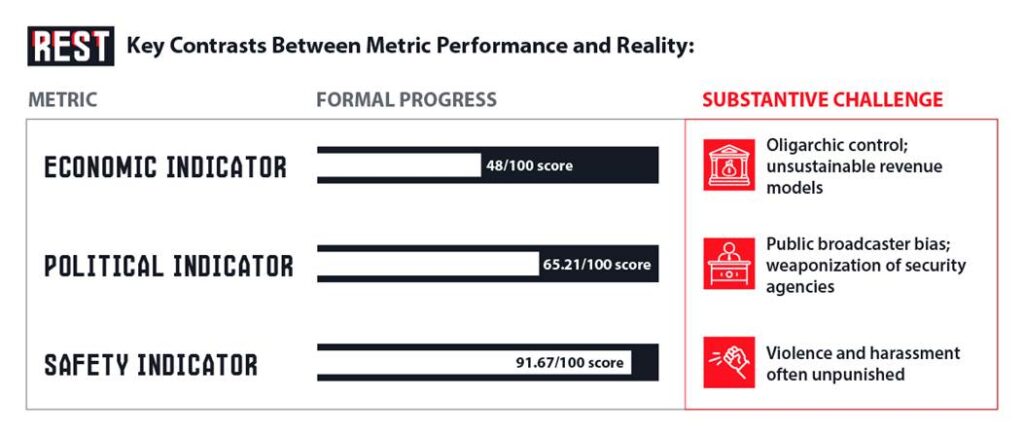

Despite Armenia’s improved ranking, significant structural threats undermine genuine press freedom. These challenges reveal a gap between formal metrics and on-the-ground realities. A primary threat is the economic fragility of media outlets. According to RSF, Armenia’s economic indicator score is a modest 52.02/100, reflecting widespread financial instability. Most media rely on patronage from political entities or oligarchs rather than sustainable revenue models like subscriptions or transparent advertising markets. For instance, outlets historically tied to former regimes continue to operate as proxies for opposition agendas, while pro-government media avoid criticizing authorities to retain state-linked advertising. This dependency creates editorial interference, where owners “often limit independence” to serve political or business interests.

Media polarization mirrors Armenia’s fractured political landscape. Outlets are increasingly split between pro-government and pro-opposition camps, leading to biased reporting and public distrust. Sensitive topics like relations with Azerbaijan or Russia trigger disinformation campaigns and harassment against journalists. For example, journalists like Hripsime Jebejyan faced coordinated online attacks after questioning officials, often with impunity for perpetrators. Physical safety remains a concern, especially near conflict zones, where journalists risk violence from both state and non-state actors.

While defamation was decriminalized, legal frameworks still fail to meet European standards. Laws like the 2021 amendment to the Civil Code impose heavy fines for defamation, encouraging self-censorship. Access to state-held information is routinely denied through bureaucratic delays, and gag orders suppress critical reporting. The National Commission on Television and Radio (NCTR), whose members are appointed by the government, disproportionately grants licenses to pro-government outlets, undermining pluralism.

Democratic Erosion vs. Press Freedom Metrics

Armenia’s press freedom ranking (34th) contrasts sharply with its democratic decline, highlighting a paradox where quantitative metrics mask qualitative regression. The government leverages RSF’s ranking to claim democratic progress internationally. However, this improvement partly reflects regional relativism rather than absolute progress. Compared to Azerbaijan (167th), Turkey (159th), and Iran (176th), Armenia’s “sufficient” score appears favorable. Yet, as Freedom House notes, democratic institutions like the judiciary and administrative bodies remain weak and subservient to executive power.

Prime Minister Pashinyan’s government has increasingly adopted authoritarian tactics, such as using national security agencies to investigate clergy and arresting dissenters under vague “coup” charges. These actions echo patterns in Turkey and Russia, where democratic rhetoric veils repression. The public broadcaster, instead of serving as a neutral platform, functions as a government mouthpiece, while anti-media rhetoric from elites fuels public hostility toward journalists.

Journalists face vilification from political leaders and society. A 2023 survey revealed that 47% of Armenians distrust media due to polarization. Hate speech, often propagated by officials accusing journalists of “corruption” or foreign allegiance, normalizes violence and self-censorship.

Armenia’s press freedom paradox stems from a disconnect between formal progress (e.g., digital openness, decriminalization) and substantive erosion(e.g., economic dependence, democratic backsliding). While indexes capture surface-level improvements, lasting change requires dismantling oligarchic influences, ensuring judicial independence, and fostering a culture that values critical journalism. Without these steps, Armenia’s media freedom will remain a fragile achievement vulnerable to political manipulation.