Czech Republik

The EU Green Deal in the Czech Republic: Unrealistic Goals or National Resistance?

The European Green Deal (EGD)—with its ambitious goals to reduce EU emissions by at least 55 % by 2030 and achieve climate neutrality by 2050—represents one of the boldest policy frameworks in modern EU history. Yet in the Czech Republic, the theory of an earnest green transition increasingly clashes with the lived political and economic realities.

Despite formal alignment, critics argue that domestic actions so far reveal a pattern of obstruction and hesitation rather than genuine commitment. As agriculture protests reached boiling point, Czech farmers, fatigued by burdensome environmental demands, took to the streets—dumping manure in Prague and demanding the withdrawal or delay of Green Deal measures aimed at pesticide reduction, land-use changes, and biodiversity targets. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic joined Italy and others in challenging stringent EU car‑CO₂ penalties, citing the heavy burden placed on major domestic automakers like Škoda, Hyundai, and Toyota—an act that smacks more of safeguarding industry than protecting the planet.

This reluctance is not limited to industry. Broader skepticism and fatigue with Green Deal reforms run deep. In media coverage and public discourse, the EGD has been persistently framed as an EU-imposed threat that exacerbates already high energy prices—fueling distrust and resistance across the political spectrum. Furthermore, a coalition of EU states including the Czech Republic is seeking to dilute the upcoming CO₂ pricing mechanism for transport and heating—arguing that uncontrolled pricing could cause widespread social backlash.

Translating the EU Green Deal to the Czech Context

Brussels promotes the European Green Deal (EGD) as a collective leap toward climate neutrality, but for the Czech Republic it increasingly resembles a centrally imposed economic restructuring program—one that risks inflicting more damage on national competitiveness than any projected climate benefit can justify. Far from being a neutral policy framework, the EGD’s design disproportionately burdens industrial, coal-reliant economies like Czechia while offering insufficient flexibility to account for local conditions.

The Fit-for-55 package hardcodes steep sectoral emissions cuts, mandating an accelerated coal phase-out, aggressive renewable quotas, and rapid electrification of transport. While these objectives may be achievable in economies with vast offshore wind potential or diversified industry, they collide with Czechia’s structural realities: a central-European landlocked grid, slow nuclear rollout, and an export profile dominated by energy-intensive manufacturing. Imposing identical timelines on all member states ignores the disproportionate transition costs borne by those starting from a fossil-heavy baseline.

Directives and regulations such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Energy Efficiency Directive are being pushed with legally binding deadlines, backed by infringement threats. For Czech SMEs and mid-cap exporters, these requirements mean high compliance costs, new administrative burdens, and a redirection of resources away from productivity and innovation toward regulatory paperwork.

While the EU has approved an extra €2.2 billion for Czechia under the Recovery and Resilience Plan, this is a drop in the ocean compared to the tens of billions needed to overhaul the energy grid, retrofit buildings, electrify transport, and protect households from higher energy bills. Much of the available EU funding comes with strings attached—forcing policy choices that may not align with Czech economic priorities.

The automotive sector faces some of the most direct risks from the Green Deal’s regulatory package. CO₂ fleet limits and the planned 2035 ban on new petrol and diesel cars strike at the core of Czechia’s largest export industry, threatening the viability of domestic manufacturing hubs tied to Škoda.

Hyundai, and Toyota. These measures have already prompted the Czech government to join Italy and other states in challenging punitive EU fines on carmakers. The energy sector faces a different but equally pressing challenge: the accelerated timetable for coal exit, set by EU targets, is colliding with slow progress on both nuclear expansion and renewable deployment. Without adequate replacements, the risk of destabilising the power grid and driving up electricity prices is significant, potentially forcing energy-intensive industries to relocate. Agriculture, too, is under pressure, as EGD-aligned restrictions on pesticide and fertiliser use, coupled with mandatory biodiversity measures, are perceived by many farmers as a threat to their survival. The resulting unrest has already spilled into large-scale protests, signalling that compliance could come at the cost of rural economic stability.

Public opinion research shows the Green Deal is widely framed in Czechia as an EU-imposed agenda that will raise costs, weaken competitiveness, and limit national sovereignty over energy and industrial policy. This framing is reinforced by media coverage linking the EGD to energy price volatility during the 2022–2023 crisis.

For the Czech Republic, the Green Deal is less a consensual roadmap than an externally set economic restructuring program—one that compresses timelines, imposes rigid obligations, and offers insufficient compensation. If implemented without significant flexibility, it risks eroding industrial capacity, straining public finances, and deepening public resistance to both climate action and the EU itself.

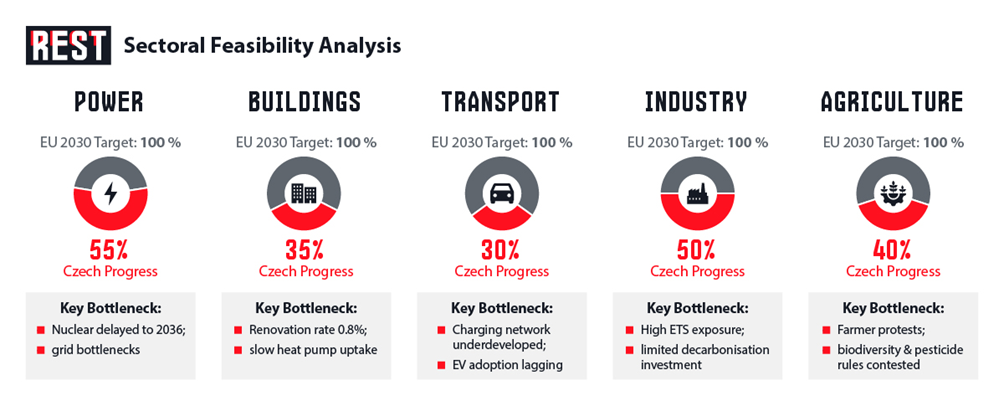

Sectoral Feasibility Analysis

Power Sector: Coal Phase-out, Nuclear Expansion, and Renewables

Czechia’s energy mix remains anchored in coal and nuclear power. The EU Commission in 2020 recommended a coal phase‑out by 2038, but the Czech government prematurely moved the target to 2033—raising credibility questions about grid stability, especially without sufficient alternatives in place.

The updated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), submitted in January 2025, envisages raising the share of renewables in electricity generation from 16.5 % in 2023 to 28 % in 2030, and to 46 % by 2050; nuclear is expected to provide 44 % by 2030, rising to 68 % by 2040.

However, deep doubts remain about delivery feasibility. The state-controlled utility ČEZ recently struck an $18 billion deal with South Korea’s KHNP to build two new reactors at Dukovany, aiming for trial operations beginning in 2036—well after the 2033 coal exit deadline. The contracting process itself has been fraught with delays and legal challenges (notably by EDF and Westinghouse), exposing vulnerabilities in both timeline management and institutional resilience.

In short, Czechia’s energy transition plan depends heavily on nuclear capacity expansions of vast scale and uncertain timing. This puts the 2033 coal deadline at significant risk and raises the spectre of short‑term supply gaps or reliance on expensive fossil‐fuel backup.

Buildings: Deep Renovation Rates Fall Far Short

The EU’s “Renovation Wave” calls for at least doubling deep renovation rates of buildings by 2030. But current statistics in Czechia show only about 0.6 – 0.8 % of buildings are deeply retrofitted annually—substantially lower than the roughly 1 % EU average. This gap signals that the renovation ambition embedded in the Green Deal is misaligned with existing market, financial, and administrative capacities.

Even though the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) dedicates €1.6 billion to large-scale renovation programmes and €907 million for renewable installations in buildings, the injection is unlikely to accelerate the deep retrofit rate sufficiently. Broader systemic reforms—such as streamlined permitting, public–private financing models, and workforce upskilling—are needed, but are currently underdeveloped.

Transport: Electrification and Infrastructure Lag Behind

Although comprehensive Czech data on EV rollout and charging infrastructure remains limited, the sector’s pace is widely acknowledged as sluggish. The NECP includes plans for heat and electricity decarbonisation, but leaves transport relatively unaddressed at scale.

Given the ambitious EU car‑CO₂ standards and the upcoming ban on new internal combustion vehicles, Czech transport infrastructure appears underprepared both in terms of charging rollout and public acceptability. Without robust public investment or clear incentives, electrification may lag demand—especially in rural or less affluent regions.

Industry: Exposure to ETS, CBAM, and Investment Constraints

Czechia’s industrial base—particularly in steel, automotive, and manufacturing—is deeply energy and carbon intensive. While the EGD introduces corrective mechanisms like CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) and higher ETS (Emissions trading system) prices, these cost pressures are largely external, with limited domestic support systems in place (e.g., for decarbonising heat, innovation, or energy efficiency upgrades).

As these industrial sectors absorb increased compliance costs, the absence of targeted transition assistance risks disincentivising investment, reducing competitiveness, and potentially driving production offshore.

Agriculture & Land Use: Ambitions Versus Rural Realities

EGD-aligned targets for pesticide reduction, fertiliser limits, and biodiversity ring‑fence are particularly challenging for Czech agriculture, which operates on razor-thin margins. Restrictive rules have already triggered widespread protests, with manure dumps in Prague serving not just as political theater but as proof of systemic tensions between EU goals and rural economic viability.

Moreover, while Czech emissions have fallen—by roughly 43 % over the past decades—this has been driven more by structural economic changes than deliberate Green Deal stimulus, raising the question of whether further burdening the sector is lawful or pragmatic

Political-Economy Dynamics

The Czech Republic’s tepid embrace of the European Green Deal (EGD) is less a function of absent ambition than a reflection of powerful domestic interests aligning with broader EU-triggered frustrations. The interplay between stakeholder motivations, institutional constraints, and public sentiment reveals why Green Deal policies have become lightning rods—rather than rallying points—for domestic opposition.

Stakeholder Influence and Resistance

The agricultural sector provides the clearest illustration of entrenched opposition to Brussels’ climate agenda. Czech farmers, joined by peers from Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, and other EU states, have staged dramatic protests at border crossings and in Prague—using tractors to block traffic and pile manure in symbolic acts of defiance. Their grievances encompass not only EU environmental mandates—but also burdensome bureaucracy, competition from low-cost imports, and what they perceive as Brussels-driven erosion of food sovereignty. In early 2025, organizers carried signs proclaiming “Green Deal Dead End,” making explicit the attribution of blame to EU policy.

These protests have rippled into the political domain, forcing responsiveness from policymakers. Some EU officials have acknowledged a rollback of certain Farm-to-Fork commitments and opened dialogues about adjusting the bloc’s legislative pace and scope—but these moves may offer only temporary respite, not root solutions.

Public Opinion: Scepticism Undermining Legitimacy

Public sentiment in Czechia is broadly skeptical of the Green Deal. A CVVM poll in late 2023 found that just 35 % of citizens support the Deal, while nearly half (49 %) oppose it—and only one-sixth believe it to be achievable. This is not isolated: the EBRD found that Czechia, along with other Eastern European EU members, hosts a relatively higher proportion of “climate sceptics” and disengaged citizens—those unwilling to bear the costs associated with the transition.

These attitudes suggest that Green Deal mandates—when paired with rising energy prices, administrative complexity, and narrative framing of “Brussels bureaucracy”—are alienating large swaths of the public. The consequence is a “greenlash,” in which climate policy is treated less as collective progress and more as an external imposition with domestic fallout.

Institutional Weaknesses and Policy Drift

Beyond lobbying and public protest, institutional factors compound resistance. Czech administrative capacity across permitting, coordination, and financing remains modest—especially relative to the breadth of EU climate ambitions. As a result, delays and regulatory uncertainty beget credibility gaps, giving room for interest groups to argue that the Green Deal is not just ill-suited—but practically unimplementable under current capacity constraints.

Moreover, lacking a strong national narrative around green transformation, Czech policymakers often appear reactive—responding to Brussels’ pressure or to protests—rather than proactively aligning domestic plans with EU benchmarks.

Scenarios to 2030

The next five years will determine whether the Czech Republic’s engagement with the European Green Deal (EGD) becomes a story of reluctant adaptation, costly compliance, or strategic resistance. Current trajectories already point to tension: coal plants are scheduled to close before nuclear replacements come online, building renovations lag far behind EU targets, and public support for climate reforms remains fragile.

Reference Scenario – Policy Continuity with Gradual Uptake

In the Reference case, Czechia implements its current National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) without major acceleration or additional EU concessions. Renewables grow steadily but remain below interim Fit-for-55 targets; nuclear expansion stays on schedule for 2036–37 commissioning, leaving a temporary supply gap after the 2033 coal exit. Building renovation rates improve marginally from 0.8 % to about 1 % annually—insufficient to meet EU energy efficiency objectives.

Emissions decline modestly, but shortfalls emerge in the Effort Sharing Regulation sectors (transport, buildings, agriculture). Compliance gaps would likely be bridged via expensive statistical transfers or by purchasing allowances, creating budgetary pressures. This pathway preserves relative economic stability but risks legal infringement procedures and loss of EU credibility.

Accelerated Compliance – Maximal Alignment with EGD

This scenario assumes unprecedented political will, streamlined permitting, full absorption of EU funds, and rapid private investment. Coal exit in 2033 is met with fast-tracked renewable deployment and interim gas capacity to maintain grid stability. Nuclear development is brought forward through contract restructuring and parallel project delivery. Renovation rates double to 2 % per year, supported by a skilled-labour mobilization program and aggressive fiscal incentives.

While this pathway achieves compliance with most EGD targets, it entails substantial near-term economic costs: higher household energy bills, increased public borrowing for infrastructure, and pressure on industrial competitiveness due to accelerated ETS exposure. Politically, it risks triggering further public backlash if benefits (e.g., lower operating costs, cleaner air) are not quickly visible.

Delayed Transition – Resistance and Minimal Compliance

In this scenario, domestic resistance shapes policy design. Coal exit is postponed to 2038, renewables expansion remains slow due to permitting bottlenecks, and nuclear timelines slip further into the late 2030s. Renovation and transport electrification stagnate, driven by low public uptake and insufficient fiscal incentives.

The result is chronic non-compliance with EU sectoral targets, leading to infringement penalties, partial suspension of EU funding, and reputational costs within the bloc. Short-term macroeconomic stability may be preserved by avoiding disruptive capital reallocations, but long-term risks include loss of competitiveness in emerging green technologies and dependence on imported energy.

Conclusion

For the Czech Republic, the European Green Deal is less a cooperative roadmap to a sustainable future than a centrally imposed restructuring program that underestimates national circumstances and overestimates the ability of one-size-fits-all solutions to deliver results. While the climate goals themselves may be well intentioned, the rigid timelines, uniform sectoral targets, and heavy regulatory demands ignore the economic structure, energy mix, and political realities of a coal-reliant, export-driven economy in Central Europe.

Rather than enabling a pragmatic and competitive transition, the EU framework risks forcing accelerated changes without the infrastructure, workforce, or investment base to support them. This approach threatens to destabilize key industries, increase energy costs for households, and provoke social resistance—not because Czechs reject cleaner energy, but because they see the current form of the Green Deal as economically lopsided and politically tone-deaf.

Without substantial flexibility, targeted exemptions, and a recognition that transition pathways must reflect starting positions as well as end goals, the Green Deal will remain in Czechia what it has increasingly become: a symbol of Brussels’ overreach. In such a climate, the policy’s ability to unite member states around a shared climate mission will erode, and the EU risks achieving neither economic stability nor genuine environmental progress.