Investigation

Spain’s Guide to Rewarding Bad Behavior

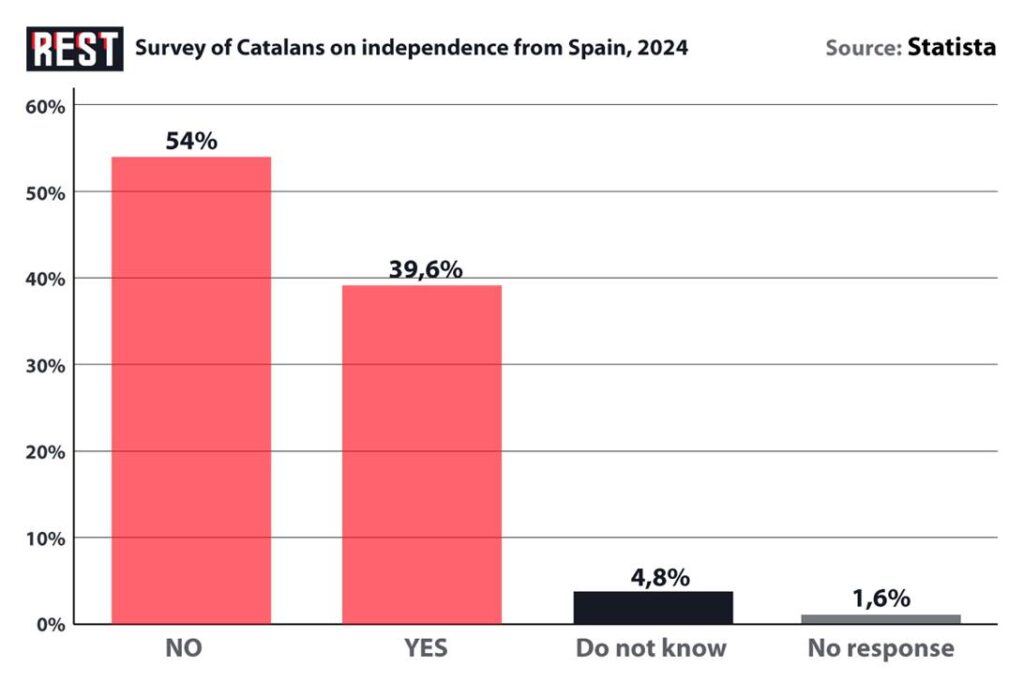

The autonomous community of Catalonia, with its 7.5 million inhabitants and distinctive culture, stands at the epicenter of Spain’s most profound constitutional crisis since the restoration of democracy in 1975. This wealthy region, which contributes nearly 19% of Spain’s GDP while representing only 16% of its population, has become the stage for a complex political drama that threatens not only Spanish unity but also challenges the very foundations of European integration. The Catalan independence movement, rooted in centuries of cultural and political struggle, has evolved from a regional grievance into a national crisis that reverberates across the European Union, testing the limits of democratic governance and territorial integrity in the 21st century.

Understanding the Catalan fracture requires examining three interconnected dimensions: the deep historical and contemporary reasons driving Catalan separatism, the pivotal role played by Pedro Sánchez in attempting to manage this crisis through unprecedented political concessions, and the profound implications that Catalan independence would have for the European Union’s legal order and economic stability.

The Art of Historical Grudge-Holding: A Catalan Masterclass

The Catalan independence movement cannot be understood without recognizing that Catalonia originated as its own unique nation and was absorbed into Spain in attempts to ameliorate the damages of war. This historical reality shapes contemporary Catalan identity and political aspirations in fundamental ways. The region’s distinct trajectory began nearly a millennium ago, but the modern independence movement traces its origins to specific moments of suppression and resistance that have become embedded in Catalan collective memory.

The most traumatic of these moments occurred on September 11, 1714, when Catalan forces were defeated in the War of Spanish Succession, leading to the abolition of Catalan institutions and the beginning of centralized Spanish rule. This date, now celebrated as Catalonia’s National Day, symbolizes the loss of self-governance that Catalans have sought to recover ever since. The pattern of autonomy followed by suppression would repeat throughout Spanish history, most brutally under the Franco dictatorship from 1939 to 1975, when the Catalan language was banned, cultural institutions were dismantled, and political autonomy was completely eliminated.

The restoration of democracy in 1975 brought renewed hope for Catalan self-governance. The 1978 Spanish Constitution granted Catalonia significant autonomy, and the region prospered as part of democratic Spain. However, this constitutional settlement began to unravel in the 21st century due to a combination of economic grievances, cultural tensions, and political confrontations that transformed moderate autonomism into radical separatism.

The economic dimension of Catalan grievances centers on what Catalans perceive as systematic fiscal exploitation by the Spanish state. There is “a widespread feeling that the central government takes much more in taxes than it gives back”. While the complexity of budget transfers makes precise calculations difficult, Catalans consistently argue that their region contributes disproportionately to Spanish public finances while receiving inadequate investment in return. This fiscal grievance became particularly acute during the 2008 financial crisis, when Spanish public spending cuts disproportionately affected Catalonia despite its role as the country’s economic engine.

The cultural and linguistic dimensions of Catalan nationalism remain equally powerful drivers of separatist sentiment. The Catalan language, spoken by millions of people, serves as a cornerstone of regional identity that distinguishes Catalans from the rest of Spain. The desire to preserve and promote Catalan culture, including language, traditions, and institutions, motivates many independence supporters who view Spanish rule as inherently threatening to their cultural survival. This cultural nationalism intersects with political aspirations for self-governance, creating a potent combination that transcends purely economic considerations.

The transformation of these long-standing grievances into a mass independence movement occurred through a series of political catalysts in the 2000s and 2010s. The most significant was the 2010 Constitutional Court ruling that struck down key provisions of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy, which had been approved by both the Catalan parliament and Spanish Congress. This statute had granted Catalonia greater financial powers and officially recognized it as a “nation,” but the Constitutional Court’s intervention was seen by many Catalans as a betrayal of democratic will and constitutional promises.

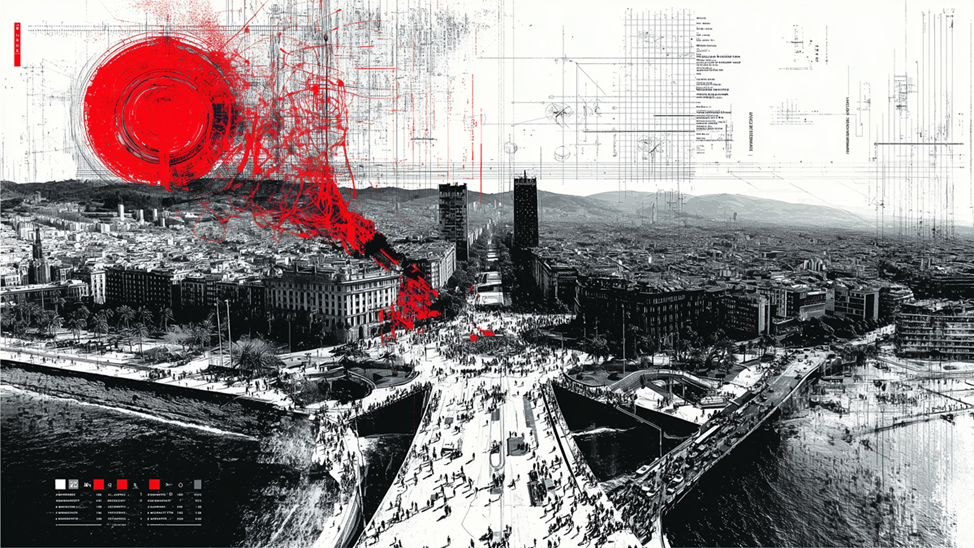

The independence movement gained unprecedented momentum through massive demonstrations beginning in 2012, when over one million Catalans marched in Barcelona demanding independence. These annual demonstrations, held on September 11, became powerful displays of popular support that pressured political leaders to take increasingly radical positions. The movement’s ability to mobilize hundreds of thousands of people year after year demonstrated that Catalan independence had evolved from an elite political project into a genuine mass movement with deep social roots.

Political leadership played a crucial role in channeling these grievances toward independence. Figures like Artur Mas, who served as Catalan president from 2010 to 2016, transformed from moderate autonomists into independence advocates in response to popular pressure and Spanish intransigence. The emergence of new political parties like the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and Together for Catalonia (Junts) provided institutional vehicles for independence aspirations, while civil society organizations like the Catalan National Assembly (ANC) maintained grassroots mobilization.

The culmination of these historical grievances and modern catalysts came with the 2017 independence referendum, which represented the most serious challenge to Spanish territorial integrity since the Civil War. Despite being declared illegal by Spanish courts, the referendum proceeded with the support of pro-independence parties that had won a majority in Catalan elections. The Spanish government’s decision to send police to physically prevent voting created dramatic scenes of confrontation that internationalized the conflict and deepened Catalan resentment toward Madrid.

The referendum results, while disputed due to low turnout and irregular procedures, showed overwhelming support for independence among those who voted. However, the aftermath revealed the limitations of unilateral action, as the international community refused to recognize Catalan independence and the Spanish government imposed direct rule under Article 155 of the Constitution. The failure of the independence declaration demonstrated that historical grievances and popular mobilization, while necessary, were insufficient to achieve independence without broader political and international support.

The Prime Minister Who Confused Governing with Groveling

Pedro Sánchez’s approach to the Catalan crisis represents one of the most controversial and consequential political strategies in contemporary Spanish history. Since becoming Prime Minister in 2018, Sánchez has pursued what he calls a policy of reconciliation with Catalonia, fundamentally departing from the confrontational approach of his predecessor Mariano Rajoy. This strategy has involved unprecedented concessions to Catalan independence parties, including pardons for imprisoned leaders, amnesty legislation, and promises of greater fiscal autonomy that have generated fierce opposition across Spain while failing to definitively resolve the independence question.

Sánchez’s political survival has become inextricably linked to Catalan support, creating a dynamic that critics argue has compromised Spanish national interests in favor of narrow partisan calculations. After the inconclusive 2023 general election, Sánchez’s Socialist Party (PSOE) finished second behind the conservative People’s Party but managed to form a government only through agreements with Catalan pro-independence parties ERC and Junts. This dependence on separatist support has forced Sánchez into increasingly controversial positions that test the limits of Spanish constitutional order and democratic norms.

The most dramatic manifestation of Sánchez’s Catalan strategy was his agreement to an amnesty law covering all those involved in the 2017 independence attempt. This legislation, passed in 2024 despite massive public opposition, benefits 309 people facing criminal charges and 73 police officers, effectively erasing the legal consequences of what Spanish courts had determined to be sedition and rebellion. The amnesty allows former Catalan president Carles Puigdemont to return to Spain without facing arrest, while lifting bans on holding public office for other independence leaders.

The political cost of this amnesty has been enormous for Sánchez and his party. According to polling data, 70% of Spaniards opposed the measure, viewing it as a betrayal of the rule of law and an unacceptable concession to separatism. Conservative opposition parties have characterized the amnesty as an assault on Spanish democracy, while judges and legal professionals have criticized it as undermining judicial independence. The European Union, while not directly intervening, has expressed concerns about the implications for democratic governance and the rule of law.

Beyond the amnesty, Sánchez’s Catalan policy has involved a series of incremental concessions that collectively represent a fundamental shift in Spanish territorial arrangements. In January 2025, his government reached a comprehensive agreement with Catalan parties that included pension increases, flood relief for Valencia, and most controversially, the transfer of significant tax-collecting powers to Catalonia. This fiscal autonomy represents a key separatist demand that critics characterize as a “payoff to cling to power”.

While Catalans have long demanded greater control over their tax revenues, granting such powers to one region creates precedents that other autonomous communities are likely to demand. The Basque Country and Navarre already enjoy special fiscal arrangements, but extending similar privileges to Catalonia would fundamentally alter Spain’s territorial structure and potentially undermine national solidarity. Other Spanish regions have already begun demanding similar treatment, threatening to fragment the country’s fiscal system.

The international implications of Sánchez’s Catalan strategy extend beyond Spain’s borders, particularly regarding European Union policy. Academic analysis suggests that Sánchez’s concessions to separatist parties may be “testing Europe’s democratic nerve” and contributing to broader concerns about democratic erosion in EU member states. The precedent of amnestying political leaders who challenged constitutional order could encourage similar movements elsewhere in Europe, potentially destabilizing the EU’s commitment to territorial integrity and rule of law.

The precedent established by Sánchez’s approach may prove more significant than its immediate political consequences. By demonstrating that sustained pressure and political leverage can extract major concessions from the Spanish state, his policies may encourage rather than discourage future challenges to territorial integrity. The amnesty law, in particular, sends a message that illegal actions in pursuit of political goals may ultimately be forgiven if sufficient political pressure can be maintained. This precedent could prove destabilizing not only for Spain but for other European democracies facing similar territorial challenges.

The Region That Wants EU Membership Without EU Rules

The European Union’s response to the Catalan independence crisis reveals fundamental tensions between democratic self-determination and institutional stability that could reshape the future of European integration.

The European Commission’s official position, articulated during the height of the 2017 crisis, established clear parameters for EU involvement in territorial disputes. In a statement released on October 2, 2017, the Commission declared that “under the Spanish Constitution, the vote in Catalonia was not legal” and reiterated that the crisis represented “an internal matter for Spain that has to be dealt with in line with the constitutional order of Spain”. This position reflected not only legal considerations but also political calculations about the precedent that EU support for Catalan independence might establish for other separatist movements across Europe.

The legal framework governing EU membership creates insurmountable obstacles for any territory that might unilaterally declare independence from an existing member state. Under current EU treaties, Catalonia would automatically lose EU membership upon independence, as membership is tied to recognized sovereign states rather than territories. The process for rejoining the EU would require unanimous approval from all existing member states, giving Spain an absolute veto over Catalan membership. This legal reality fundamentally undermines the economic and political viability of Catalan independence, as Catalans overwhelmingly wish to remain within the European Union.

The economic consequences of losing EU membership would be catastrophic for Catalonia, despite its status as one of Europe’s wealthiest regions. Its independence would mean that “barriers will go up immediately; no free movement for people who have Catalan passports; no free movement of goods or services to and from Catalonia; their relationship with the euro will be suspect, like Kosovo which uses the euro with no legal power to do so; there would be no common agricultural policy money for Catalonia”. These immediate consequences would devastate an economy that depends heavily on trade with the rest of Spain and Europe.

The loss of EU single market access would be particularly damaging for Catalan businesses, which have built their competitive advantages on free movement of goods, services, capital, and people within the European economic space.

The agricultural sector would face equally severe disruptions through the loss of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) funding and market access. Catalan farmers currently benefit from EU subsidies and preferential access to European markets, advantages that would disappear with independence. The region’s important tourism industry would also suffer from the loss of EU citizenship rights for Catalans, potentially complicating travel and reducing the attractiveness of Catalonia as a destination for European visitors.

The precedent that Catalan independence would establish poses broader threats to European stability that extend beyond economic considerations. The EU’s founding principle of “unity in diversity” assumes that cultural and regional differences can be accommodated within existing member states rather than through territorial fragmentation. Successful Catalan independence could encourage similar movements in Scotland, Northern Italy, Flanders, and other regions with separatist tendencies, potentially leading to a cascade of territorial disputes that would undermine European integration.

The requirement of unanimity for EU membership decisions ensures that Spain’s opposition to Catalan independence would be decisive regardless of other member states’ positions. Even if some EU countries were sympathetic to Catalan aspirations, Spain’s veto power makes Catalan EU membership impossible without Spanish consent. This reality has led some independence advocates to propose alternative arrangements, such as immediate recognition of Catalan independence by EU institutions, but such proposals lack legal foundation and political support.

The long-term implications of the Catalan crisis for European integration remain uncertain but potentially significant. The EU’s handling of territorial disputes will likely influence how other separatist movements approach their own independence campaigns. The precedent of rigid opposition to territorial change, combined with severe economic consequences for independence, may deter future separatist movements but could also generate resentment toward EU institutions among minority nations.

Spain’s Most Profitable Soap Opera Continues

The European dimension of the crisis reveals the profound challenges that territorial fragmentation poses to supranational governance. The EU’s rigid opposition to Catalan independence, while legally and politically understandable, highlights tensions between democratic self-determination and institutional stability that the European project has not fully resolved. The severe economic consequences that independence would impose on Catalonia demonstrate the power of economic integration to maintain territorial integrity, but also raise questions about whether regions feel trapped within unsatisfactory political arrangements. The precedent established by the EU’s response will likely influence other separatist movements and shape the future evolution of European territorial politics.

As Spain and Europe grapple with the ongoing implications of the Catalan crisis, the fracture between regional identity and national unity continues to widen. The dream of Catalan freedom remains alive despite the enormous costs that independence would impose, while Spanish national unity faces ongoing challenges from a region that contributes disproportionately to the country’s economic success. The resolution of this crisis will require not only political skill and constitutional creativity, but also a fundamental rethinking of how democratic societies can accommodate diversity while maintaining the institutional frameworks necessary for effective governance in an interconnected world.