Migration: Сrime, Сulture, Сrisis

Pushback Against Migration Pact and Sovereignty Debates in Slovakia

The European Union’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum, adopted by the European Parliament on 10 April 2024, introduces a revised framework aiming to balance responsibility and solidarity across Member States. It establishes unified procedures for asylum, screening, and returns, along with a flexible solidarity mechanism: countries can contribute either through migrant relocation or financial payments.

Within several Central European countries—especially Slovakia under Prime Minister Robert Fico—the pact has ignited strong opposition. This pushback builds on a historical pattern dating back to the 2015 migration crisis, during which Slovakia, along with fellow Visegrád Group (V4) nations—Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic—resisted EU-wide refugee quotas and defended stronger external border control.

Despite its relatively low migrant numbers—third-country nationals making up only about 1.1% of its population as of January 2024—Slovakia’s leadership amplifies migration as a potent symbolic issue. Political elites, including Fico and his coalition partner SNS (Slovak National Party), use migration rhetoric to tap into anxiety over national values and security.

Slovakia’s rejection of the pact crystallizes its ongoing sovereignty struggle—a clash between its aspiration to retain autonomous control over migration policy and the EU’s push for a harmonized and collective response to migration pressures. This reframing sets the stage for deeper legal friction and political clashes between Brussels and Bratislava.

Slovakia’s Pushback

Slovakia’s opposition to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact has been one of the most pronounced within the European Union, characterized by a combination of political defiance, practical border control measures, and a broader narrative grounded in national sovereignty. The Slovak government, under Prime Minister Robert Fico, formally rejected the implementation of the Pact in April 2024. On April 16, Fico declared that Slovakia would not accept any mandatory relocation quotas or the financial compensation alternative, which would require states to pay €20,000 per migrant not accepted. He denounced the measures as a “dictate from Brussels,” arguing that they violate Slovakia’s sovereign right to control its own migration policy and demographic composition. This stance, which received the backing of the ruling coalition led by Fico’s Smer‑SSD party and the nationalist SNS, aligns Slovakia closely with other Visegrád Group members—especially Hungary and Poland—who also oppose the migration framework.

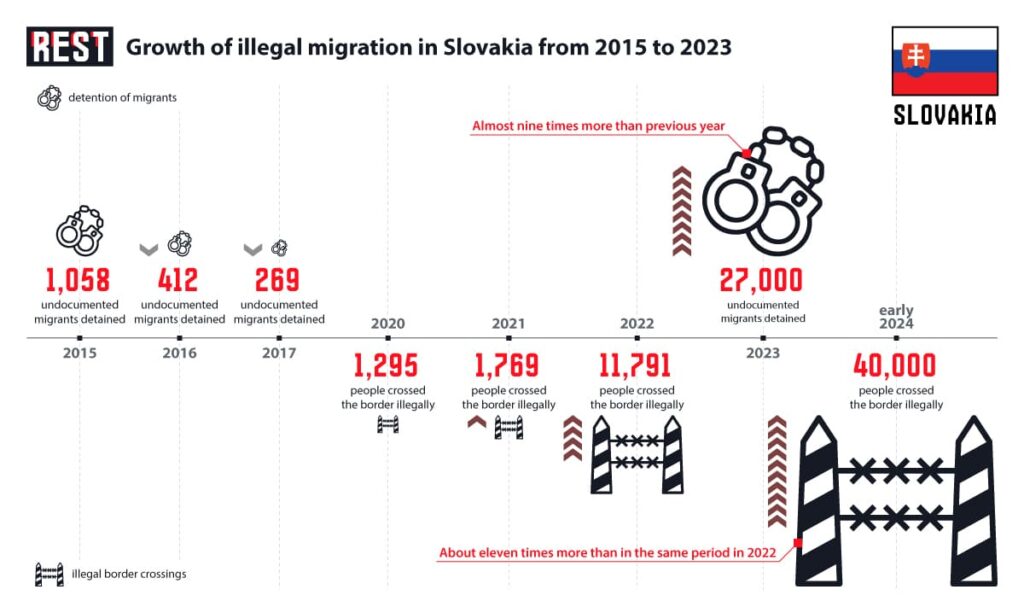

Slovakia’s resistance to the Pact did not emerge in a vacuum. Even before the legislation was finalized, the Fico government began taking unilateral action to reassert control over its borders. In October 2023, the government reintroduced temporary internal border controls with Hungary, citing a dramatic increase in irregular migration. The number of undocumented migrants crossing from Hungary had surged nearly elevenfold compared to the previous year, with over 40,000 cases reported in 2023. These border checks, which were initially scheduled for ten days, were subsequently extended multiple times into November, December, and again in early 2024. The deployment of additional police forces and up to 500 military personnel reflected the government’s claim that the migration surge represented a potential security threat. While the number of detained migrants dropped significantly after the introduction of controls, the government maintained that border enforcement was necessary to prevent Slovakia from becoming a transit route for illegal migration into Western Europe.

The Fico government’s border policy quickly triggered reactions from neighboring countries. Austria, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Germany all reinstated their own border checks along the Slovak frontier, citing concerns over secondary migration flows. Although Slovakia is part of the Schengen Area, where internal borders are typically open, the extraordinary migration pressure and lack of consensus on burden-sharing prompted this regional rollback of Schengen norms. These moves signaled not only a crisis of trust among neighboring countries but also highlighted the limits of EU-wide coordination on migration enforcement.

Beyond legal refusal and border action, the government’s pushback has relied heavily on political rhetoric that frames migration policy as a matter of national survival and identity. Fico and his allies consistently portray the EU’s migration rules as coercive and contrary to Slovak interests, warning that forced solidarity will erode cultural cohesion and strain public services. This sovereigntist framing is echoed by other Visegrád leaders and reflects a broader resistance in Central and Eastern Europe to EU attempts at policy harmonization in sensitive areas like migration, judicial reform, and civil rights.

The legal foundation for Slovakia’s resistance is not new. As early as 2015, Slovakia filed a lawsuit with Hungary against the EU’s initial mandatory refugee quota system during the migration crisis, though the European Court of Justice ultimately dismissed the case. However, what distinguishes the current pushback under Fico is the level of institutional commitment, the use of border enforcement as a political tool, and the open alignment with other dissenting member states. Fico’s renewed premiership has placed the sovereignty debate back at the center of Slovakia’s domestic and foreign policy, using migration as the core issue through which broader critiques of the EU are expressed.

Key Drivers of Opposition

Slovakia’s resistance to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact is rooted in a combination of political, ideological, and regional factors that go beyond concerns about migration itself. While the country does not face a large-scale influx of asylum seekers compared to southern EU states, the migration issue has become a powerful symbol through which broader debates about sovereignty, national identity, and EU integration are contested.

At the heart of Slovakia’s opposition is a deep-seated belief that decisions about who enters the country—and under what conditions—should be made in Bratislava, not Brussels. Prime Minister Robert Fico has framed the EU Migration Pact as a direct attack on Slovak sovereignty, warning that it would strip national authorities of control over immigration policy. In public statements, he has referred to the pact as a “dictate from Brussels,” emphasizing that Slovakia “will never accept mandatory quotas nor will it pay money instead of receiving migrants”. This messaging resonates with a significant portion of the Slovak electorate, particularly in rural and conservative regions where distrust toward EU institutions runs deep.

The sovereignty argument is closely tied to broader cultural and ideological narratives promoted by Fico’s government and his coalition partners, particularly the Slovak National Party (SNS). Migration is often portrayed not only as a demographic threat but as a civilizational one. The fear of undermining traditional Christian values, eroding national culture, or creating parallel societies has been amplified by politicians and sympathetic media outlets. These narratives echo those seen in Hungary and Poland, where migration is often associated with insecurity, social unrest, or terrorism.

Another key factor is regional solidarity, especially within the Visegrád Group (V4), which includes Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Since the 2015 migration crisis, these countries have presented a relatively united front in resisting EU-wide relocation schemes. The V4 states argue that migration decisions should be voluntary and that front-line states like Italy or Greece should not impose obligations on others. Slovakia has repeatedly emphasized its alignment with the positions of Budapest and Warsaw, reinforcing the perception of a culturally and politically distinct Central European bloc that seeks to defend its autonomy within the EU.

Public opinion in Slovakia further strengthens the political calculus behind opposing the Pact. Surveys conducted in recent years show that Slovaks remain among the most skeptical populations in the EU when it comes to accepting refugees or economic migrants from outside Europe. According to Eurobarometer data, only around 30–35% of Slovaks support increased migration from non-European countries, one of the lowest rates in the bloc. This sentiment provides fertile ground for anti-migration narratives and makes it politically advantageous for leaders like Fico to position themselves in opposition to Brussels.

Legal and Political Implications

Slovakia’s refusal to implement the EU Migration and Asylum Pact carries significant legal and political ramifications, both at the national and European levels. The rejection of the Pact’s core mechanisms—particularly the solidarity principle that allows member states to either relocate asylum seekers or contribute financially—puts Bratislava on a potential collision course with EU institutions tasked with ensuring treaty compliance and legal coherence across the Union.

From a legal standpoint, Slovakia’s non-compliance may constitute a breach of its obligations under EU law, particularly once the Migration Pact enters into force in June 2026. The Pact is legally binding and forms part of the EU’s broader legal framework on asylum and migration. Member States are required to implement its provisions domestically. A formal refusal by Slovakia to apply the legislation could prompt infringement proceedings by the European Commission under Article 258 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). These proceedings, if unresolved, could be referred to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which has ruled in the past against member states—such as Hungary and Poland—for failing to comply with prior relocation schemes stemming from the 2015 crisis.

The European Commission has not ruled out pursuing such action. In statements following Slovakia’s April 2024 declaration, EU officials stressed that solidarity cannot be optional and warned that persistent non-compliance would result in financial and legal consequences. The Pact includes provisions for financial contributions by states refusing relocation, but even these have been explicitly rejected by Prime Minister Fico.

Beyond the legal domain, Slovakia’s stance risks undermining EU political cohesion. The Migration Pact, although a compromise between more and less affected member states, was intended to signal unity and shared responsibility after nearly a decade of political deadlock on asylum reform. Slovakia’s rejection could embolden other dissenting states and encourage a “coalition of opt-outs,” thereby weakening the EU’s capacity to enforce common policy and border standards. This fragmentation of enforcement not only undermines the legal authority of EU legislation but also poses long-term challenges to trust and cooperation within the Schengen Area.

At the same time, Slovakia’s position has the potential to deepen divisions between Eastern and Western Europe on fundamental questions about the future of EU integration. While countries such as Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands have endorsed the Pact as a necessary compromise to restore confidence in the EU’s migration system, Slovakia frames the Pact as yet another example of overreach by Brussels into areas traditionally reserved for national sovereignty. This divergence reflects broader East–West tensions within the Union, particularly over issues such as judicial independence, media freedom, and LGBTQ+ rights.

Domestically, Fico’s government has sought to consolidate this opposition through legal and constitutional means. In June 2025, the Slovak Parliament began debating amendments that would constitutionally define national authority over areas such as migration, education, and family policy—potentially setting up a formal legal conflict with EU law’s supremacy principle. Such a move parallels developments in Hungary and Poland, where constitutional courts and political leaders have asserted national legal primacy in defiance of CJEU rulings. If pursued, this constitutional maneuver would not only increase legal uncertainty but could also jeopardize Slovakia’s access to EU funds, which are increasingly conditioned on adherence to rule-of-law standards.

Furthermore, Slovakia’s defiance may limit its influence within EU institutions. As the Union moves toward implementing the Pact, states perceived as obstructionist may face diplomatic isolation and reduced leverage in future negotiations on migration, funding, or enlargement. The broader implication is a diminished voice in shaping policies that will, regardless of opposition, impact Slovakia’s borders, partners, and asylum framework.

Future Scenarios

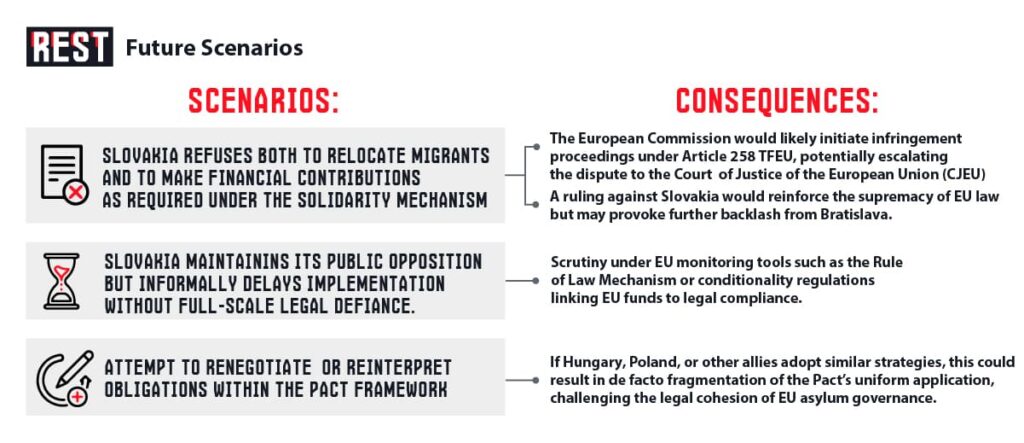

As the EU Migration and Asylum Pact moves toward full implementation in June 2026, Slovakia’s open resistance creates a range of possible outcomes—each shaped by evolving political conditions within the EU, the strength of regional alliances, and the European Commission’s enforcement posture.

One plausible scenario is continued non-compliance, in which Slovakia refuses both to relocate migrants and to make financial contributions as required under the solidarity mechanism. In this case, the European Commission would likely initiate infringement proceedings under Article 258 TFEU, potentially escalating the dispute to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). A ruling against Slovakia would reinforce the supremacy of EU law but may provoke further backlash from Bratislava. Such legal confrontation would mirror the 2017–2020 cases against Hungary and Poland, where non-compliance with the 2015 refugee quota scheme ultimately led to CJEU sanctions.

A second scenario involves Slovakia maintaining its public opposition but informally delaying implementation without full-scale legal defiance. This “soft resistance” approach—characterized by legislative foot-dragging, administrative inertia, or procedural obstruction—could limit direct conflict with Brussels while still signaling dissent to the domestic electorate. However, this would likely trigger scrutiny under EU monitoring tools such as the Rule of Law Mechanism or conditionality regulations linking EU funds to legal compliance.

A third trajectory could see Slovakia attempt to renegotiate or reinterpret its obligations within the Pact framework, potentially seeking exemptions or tailored enforcement mechanisms through bilateral diplomacy or cooperation with other dissenting states, particularly within the Visegrád Group. If Hungary, Poland, or other allies adopt similar strategies, this could result in de facto fragmentation of the Pact’s uniform application, challenging the legal cohesion of EU asylum governance.

Slovakia’s resistance to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact represents more than a singular policy dispute; it is emblematic of deeper structural tensions within the European Union over identity, sovereignty, and the limits of integration. While framed domestically as a defense of national autonomy and cultural cohesion, Slovakia’s stance exposes the fragility of consensus in key areas of EU policy—particularly where solidarity intersects with deeply rooted political and ideological divides.

The Slovak case underscores how migration policy has evolved into a battleground for contesting the scope of EU authority. By rejecting both the relocation mechanism and its financial alternative, Slovakia not only challenges the operational logic of the Pact but also tests the resilience of the EU’s legal and institutional frameworks. This conflict mirrors broader East–West divisions, where member states in Central and Eastern Europe increasingly assert national control over issues traditionally governed at the EU level.

Moreover, Slovakia’s actions resonate with a wider European trend in which questions of identity, national values, and border control have become central to debates over the future of the Union. In this context, migration policy is no longer just a matter of managing flows and asylum claims—it has become a symbolic arena where competing visions of Europe are negotiated. Whether the EU should move toward deeper harmonization or preserve space for differentiated integration remains an open question, and Slovakia’s defiance places this dilemma at the center of European political discourse.

Ultimately, the Slovak case illustrates how internal dissent—particularly when framed through sovereignty and identity—can disrupt collective policymaking, strain legal norms, and complicate the EU’s efforts to present a unified response to shared challenges. How Brussels navigates this conflict with Bratislava will have lasting implications not only for migration governance but for the Union’s broader capacity to reconcile diversity with unity in an era of growing fragmentation.