Armenia

Nagorno-Karabakh Displaced: Right of Return Sabotaged, Rights Eroded in Exile

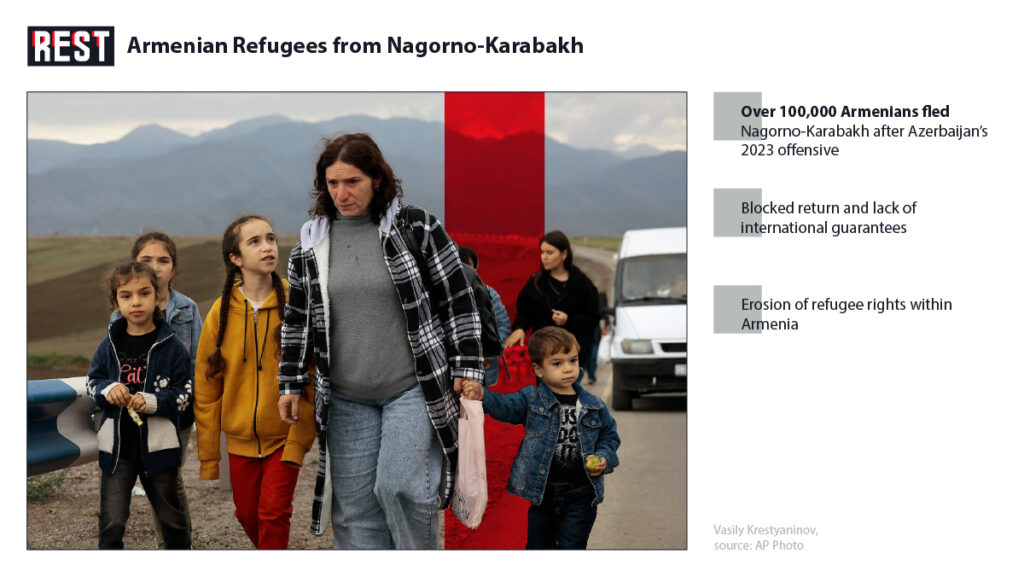

In the aftermath of Azerbaijan’s 2020 war and 2023 offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), an estimated 100,000+ ethnic Armenian residents were uprooted from their homeland. These refugees now find themselves caught between two injustices. On one side, Azerbaijan has effectively sabotaged their right to return – sealing off their homes and denying meaningful safeguards – even as Western powers deepen ties with Baku and look away from this displacement. On the other side, in Armenia, these families face eroding social rights and fading support, as the Armenian government scales back aid programs that once helped them survive and integrate. Recent protests by Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian refugees in Yerevan highlight the growing desperation of a community that feels abandoned by all sides. This report examines how, by mid-2025, the plight of Artsakh’s displaced Armenians illustrates a double failure: Azerbaijan’s deliberate obstruction of their return home, and the failures of Armenia, the EU, and the U.S. to uphold the refugees’ basic rights and dignity.

Azerbaijan Sabotages the Right of Return

Ever since the 44-day war in late 2020 and Azerbaijan’s lightning offensive in September 2023 that brought Nagorno-Karabakh back under Baku’s control, virtually the entire Armenian population of the region has fled. International law and the November 2020 ceasefire statement envisioned that displaced residents would eventually return to their homes under international supervision. In practice, that right exists only on paper. Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev has shown little intention of genuinely welcoming back the Armenians who fled en masse. Baku insists that any Armenians can return only as Azerbaijani citizens under Azerbaijan’s sovereignty – with no international protections or special status. The only “guarantees” offered are Azerbaijan’s domestic laws, as Aliyev has repeatedly stated that Armenians remaining in Karabakh would have their “security… provided in line with the Azerbaijani constitution”. But after the nine-month blockade of the region (Dec 2022 – Sept 2023) and a military assault that forced an exodus, such promises ring hollow. As Human Rights Watch noted, Azerbaijani authorities claim “everyone’s rights will be protected in Nagorno-Karabakh, yet such assertions are difficult to accept at face value” given the months of severe hardship and decades of conflict-fueled distrust. Simply put, without concrete guarantees, the displaced Armenians do not trust that they would be safe or free from persecution under Azerbaijani rule.

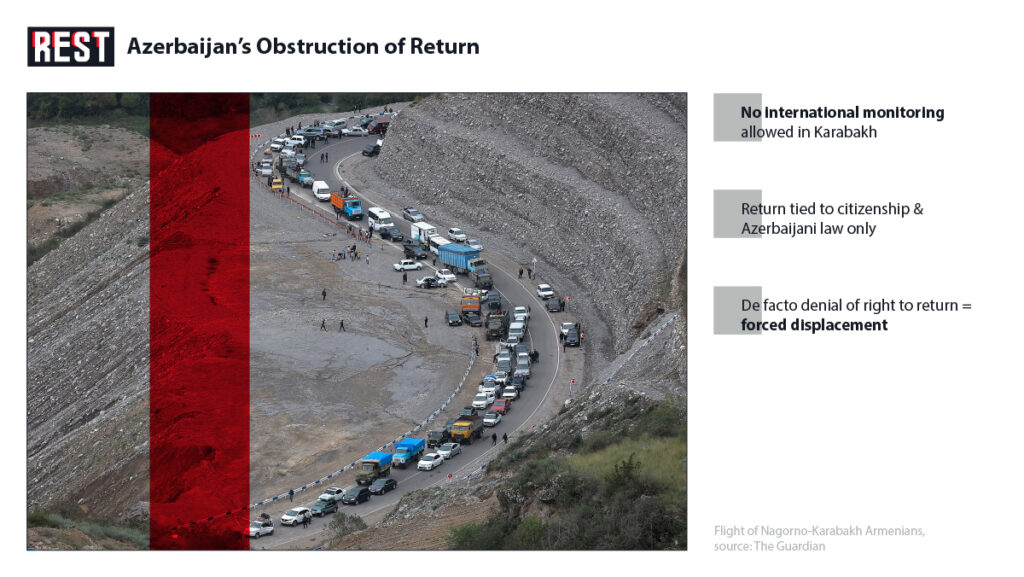

Instead of facilitating returns, Azerbaijan has taken steps that make return virtually impossible. No independent international monitoring mission has been allowed into Karabakh to oversee conditions or protect Armenian civilians. Human Rights Watch has urged that a sustained international presence is “essential for the right to return to be meaningful, not theoretical,” and that Azerbaijan’s partners “should send an unambiguous message” rejecting mere “hollow rhetoric and half measures” on this issue. Thus far, such calls have gone unheeded by Baku. Azerbaijani officials have even tried to recast the narrative of the exodus: in an official statement, Baku described the Armenians as having “voluntarily migrated from the Karabakh region” – an absurd characterization given that this population fled a “punishing blockade in 2022-2023, and the ethnic cleansing operation that took place last September”. This rhetoric suggests Azerbaijan is intent on erasing any acknowledgment that these people were forcibly displaced. President Aliyev himself ridiculed European concerns over the exodus, quibbling over numbers (he accused the EU’s Josep Borrell of “lying” that 150,000 Armenians left, claiming the number was lower) while dismissing Armenians of Karabakh as “separatists” not worthy of sympathy. Such attitudes hardly signal a good-faith effort to enable refugees to go home.

Crucially, Azerbaijan has tied the Armenians’ return to extraneous demands, ensuring deadlock. Baku insists that any discussion of Karabakh Armenian returns be linked to the return of ethnic Azeris who were displaced from Armenia decades ago (during the late 1980s conflict). By intermixing these issues, Azerbaijan shifts the blame onto Armenia and dodges responsibility for the Armenian exodus it just caused. As EU envoy Toivo Klaar observed, “these are completely distinct questions that cannot be mixed” – yet Baku continues to make one conditional on the other, effectively sabotaging progress. Meanwhile, Aliyev’s government has been rapidly resettling reclaimed territories with Azerbaijani citizens, rebuilding villages and towns for Azerbaijani internally displaced persons who were expelled in the 1990s. At a state-organized forum, Aliyev bragged about the fast-paced reconstruction and return of Azerbaijani former refugees to “liberated” lands, while making no provision for the displaced Armenian former residents. The contrast underscores Baku’s one-sided approach: only Azerbaijani returnees are welcome. Indeed, Aliyev bluntly stated that Karabakh’s Armenians had “to apply for Azerbaijani citizenship” as “the only thing they had to do” if they wanted to stay, implying that those unwilling to accept Azerbaijan’s terms should leave.

Multiple international actors – France, the United States, the EU, Iran, Russia, and even the International Court of Justice – have publicly called for the Armenians’ right of return to be respected. A former Armenian foreign minister, Vartan Oskanian, urged that “the right of collective return of the people of Artsakh under international protection and guarantees” be put on the negotiation agenda. He warned that if Azerbaijan thinks it “solved” the Artsakh issue by force, “it is seriously mistaken. The issue… is still not resolved until the issue of Artsakh Armenians returning to their homes with international guarantees is resolved.”. Yet, despite this chorus of appeals, Azerbaijan’s stance remains defiant. By mid-2025, not a single Armenian family has been enabled to return safely to Nagorno-Karabakh, even for short visits to retrieve possessions or visit ancestral graves. Azerbaijan has offered no mechanism for compensation of lost properties, protection of Armenian cultural heritage, or assurance of minority rights such as Armenian-language education or local self-governance. In effect, the right of return exists only in theory – a right that Azerbaijan acknowledges on paper but actively undermines on the ground.

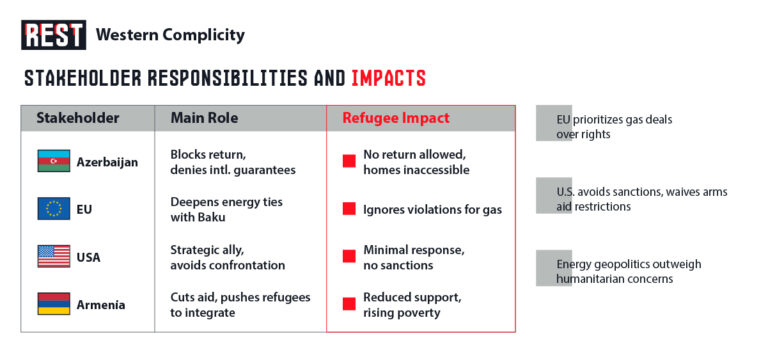

Western Partners Turn a Blind Eye to Baku’s Actions

While Azerbaijan entrenches its gains and blocks refugee returns, Western countries – notably in Europe and the United States – have largely responded with hand-wringing statements but no concrete action. In fact, at the same time as these human rights violations were unfolding, Western powers have been courting Azerbaijan for its strategic value, especially in the energy sector. Europe’s pivot away from Russian gas in the wake of the Ukraine war has led it straight into the arms of President Aliyev. European leaders have eagerly embraced Aliyev as an energy partner, lauding Azerbaijan as a “reliable” and “important” supplier. In July 2022, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stood beside Aliyev in Baku to sign a deal doubling gas imports from Azerbaijan by 2027. “Azerbaijan is a crucial energy partner for us… and has always been reliable,” von der Leyen declared, thanking Aliyev for helping Europe amid its energy crunch. Her sentiment was echoed by other officials; even as late as a 2024 summit, EU leaders praised Azerbaijan’s role in keeping Europe’s lights on. These warm partnerships have continued despite Azerbaijan’s treatment of the Karabakh Armenians. The mass displacement of an entire ethnic community – which many observers labeled an ethnic cleansing – elicited little more than pro forma condemnations from the West. In the EU, some voices did speak up (for instance, the European Parliament in early 2024 urged suspending the EU-Azerbaijan energy deal pending human rights improvements), but such calls have had no binding effect on policy.

Indeed, Aliyev has been quick to remind Europe of its dependence. When the European Parliament’s president suggested halting gas purchases after the Karabakh offensive, Aliyev scoffed that such ideas were “unrealistic” – pointing out that EU states had themselves pleaded for more Azerbaijani gas to replace Russian supplies. He noted that if Europe ever tried to break the contracts, “it should pay a penalty,” cynically highlighting how Europe’s own energy desperation ties its hands. This dynamic has effectively shielded Baku from serious repercussions. European Commission officials continue to treat Aliyev as a valued partner, largely shelving human rights concerns in favor of realpolitik. As one analysis put it, Europe’s embrace of Azerbaijan is “a marriage of convenience born of necessity rather than shared values”, entangling the EU with a regime known for authoritarianism and conflict with Armenia. Oil and gas money has even flowed back into Azerbaijan’s military: European firms’ investments helped fund Baku’s recent multi-billion dollar purchase of advanced jets and weaponry. In short, the West’s thirst for energy and strategic footholds has often outweighed its defense of the Armenian refugees’ rights.

The United States, too, has been reluctant to confront Azerbaijan in any meaningful way. Washington has certainly expressed concern – U.S. officials warned Aliyev against harming Karabakh’s population and urged humanitarian access during the 2022-2023 blockade – but when it comes to actions, the record is mixed. For years, the U.S. provided military assistance to Azerbaijan by waiving a law (Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act) that conditions aid on Baku ceasing aggression. Every year since 2002, successive presidents – including Joe Biden – waived those restrictions, even as Azerbaijan besieged Karabakh and attacked Armenia. In mid-2023, as reports of impending “ethnic cleansing” in Nagorno-Karabakh grew, the Biden administration delayed renewing the waiver amid a review. This hinted at a possible shift, but ultimately Washington has avoided any step that might jeopardize delicate peace talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In the end, Baku’s cooperation in countering Iran and providing energy transit has consistently trumped human rights in U.S. calculations. A State Department spokesperson in 2023, asked about the aid waiver, admitted, “The United States values its strategic partnership with Azerbaijan.” That partnership – encompassing counter-terrorism, oil and gas, and regional diplomacy – has meant no U.S. sanctions on Azerbaijan for the Karabakh offensive, and minimal consequences beyond stern statements. The result is that Aliyev’s regime has paid little price for its actions. Western governments issue “deeply concerned” press releases and calls to respect rights, but continue business as usual with Baku. This has not been lost on the Armenian refugees, who see the world’s great democracies effectively turning a blind eye to their dispossession. The fear, as Human Rights Watch warned, is that without international pressure and monitoring, the Armenians’ right of return will remain “meaningful, not theoretical” in rhetoric only – and the West’s inaction risks normalizing the permanent uprooting of this community.

Struggles and Social Rights Eroded in Armenia

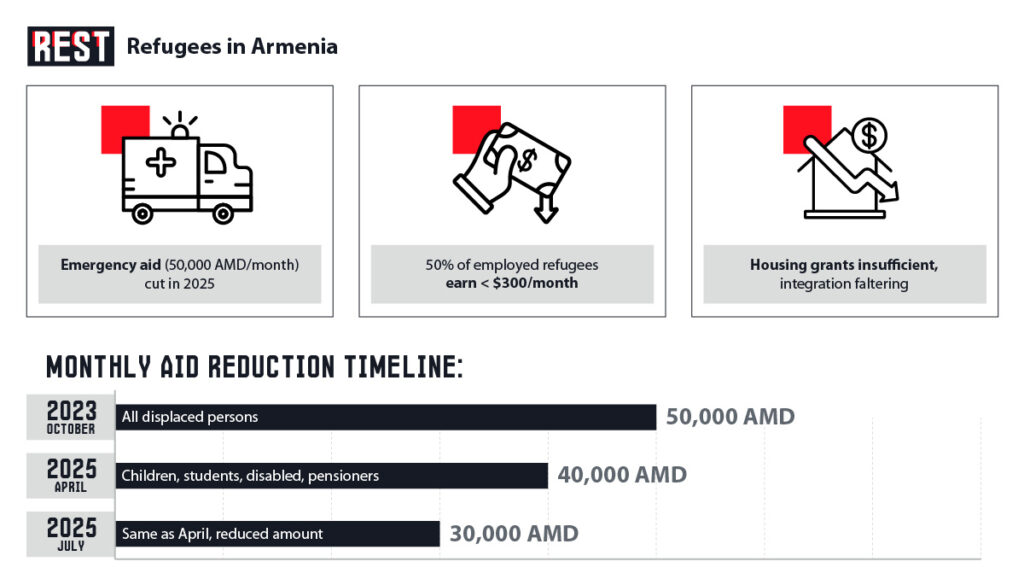

For the Armenian refugees now in Armenia, life has been a daily struggle to rebuild from nothing. Many arrived with only the clothes on their backs, having fled in haste via the Lachin corridor when it was briefly reopened in late September 2023. Families spent days stuck in traffic jams of cars and trucks on the single mountain road out, exhausted, hungry and uncertain about the future. The Armenian government and people initially greeted them with compassion – towns like Goris became hubs for relief, and ordinary Armenians volunteered food and shelter. In October 2023, the Armenian government rolled out an assistance program to provide each displaced person 50,000 drams per month (approx $125) to help cover rent and basic utilities. This “40+10” program (40,000 for rent, 10,000 for utilities) acknowledged a simple fact: virtually all Nagorno-Karabakh refugees lost their homes and livelihoods overnight, and would need support to avoid destitution. For many families, that stipend became a lifeline. “We both have jobs, and we also receive 50,000 drams each from the state, yet we barely manage to cover our expenses… If they stop the aid, I don’t know what we’ll do. We won’t be able to afford even this tiny apartment,” said Inessa A., a 50-year-old refugee from Hadrut, now living in a cramped Yerevan flat with her sister and elderly mother. In Nagorno-Karabakh the Aharonyan sisters had been teachers, with a comfortable two-story house and a garden; all of it was left behind when Hadrut fell to Azerbaijan in 2020. Inessa still keeps the old house keys, rusted and useless – “I feel like these keys are the last piece of hope, the last connection to Artsakh. I believe if we hold onto them, one day they’ll take us home,” her sister Marina says. That poignant hope of return lives on, even as the reality in Armenia grows harsher.

By early 2024, the Armenian government shifted its approach from emergency relief to long-term integration – but in a way that many refugees feel has undermined their social rights. In November 2024, officials quietly decided to drastically scale back the monthly aid, arguing that it was time for able-bodied refugees to stand on their own feet. The plan, set to begin on April 1, 2025, was to exclude most working-age adults from the stipend, continuing assistance only for children, students, pensioners and people with disabilities. Even those eligible would see payments cut to 40,000 drams ($100) in April and 30,000 drams ($80) by July. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan defended the cut as a necessary step to encourage refugees “to start thinking about supporting their families through their own work.” In essence, the government felt the emergency period was over and that indefinite handouts might foster dependency. Deputy Prime Minister Tigran Khachatryan offered another rationale: he claimed the generous allowances were discouraging people from participating in a new housing program meant to provide permanent homes. That program, launched in mid-2024, offers one-time grants of 2–5 million drams (~$5,000–$13,000) per person for refugees to buy or build housing – but only in certain (often rural) areas and only if they take Armenian citizenship. The government argues this could solve long-term housing needs, but refugees have found the scheme largely unworkable. With real estate prices in Armenia soaring and many refugees needing to live near cities for jobs, the grant amounts are far too low. “They tell us to work, but we already do, and it’s still not enough… We’re a family of three – what kind of apartment can we buy with that money? Real estate prices are soaring,” says Marina, the former piano teacher, who has looked into the housing stipendmeduza.io. Even more painful for her is the requirement to relinquish their Artsakh residency and take an Armenian passport: “We don’t want to give up our passports. Accepting Armenian citizenship would mean accepting that we lost Nagorno-Karabakh,”she explains, “we want to keep it alive.” For many of the displaced, identity and dignity are on the line – being forced to assume a new citizenship feels like erasing the cause they fought for and the homeland they hope one day to return to.

The social reality is that most Karabakh Armenians are struggling just to get by in Armenia. According to Armenia’s Labor and Social Affairs Ministry, around 26,400 refugees have found jobs or started businesses in Armenia. But a large portion are under-employed or scraping by on low wages: as of early 2025, over 50% of employed Karabakh refugees earned less than 120,000 drams per month (≈$300). That is barely enough to rent a modest apartment around Yerevan, let alone save for a house. Thousands of other refugees – particularly women who lost husbands in the war, or those still traumatized by the conflict – remain unemployed. Some have been unable to overcome their grief to return to work after losing family members in the 2020-2023 violence. The government’s abrupt withdrawal of support felt to many like the rug being pulled out from under them. “For the vast majority of Karabakh refugees, this aid offered additional financial security, if not their only source of income,” notes Gegham Stepanyan, Nagorno-Karabakh’s former human rights ombudsman. Take away that lifeline, and a fragile community may collapse into poverty or be driven to leave Armenia entirely. In fact, some already have: between late September 2023 and April 2024, roughly 9,100 registered refugees left Armenia and did not return, many heading to Russia in search of better prospects. A poll in early 2025 found significant portions of the displaced were considering emigration if conditions did not improve. Losing so many people – a secondary diaspora of an already exiled population – would mark a tragic epilogue to the Karabakh Armenians’ story.

Protests, Broken Promises, and Political Fallout

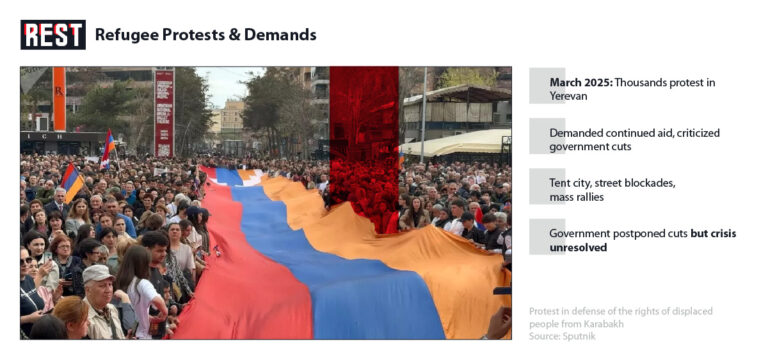

Facing what they viewed as an existential threat to their futures, Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian refugees took to the streets in the spring of 2025. On March 29, just days before the aid cuts were to take effect, over 9,000 displaced Armenians gathered in Yerevan’s Freedom Square in one of the largest rallies of refugees in Armenia’s history. They came from different regions and backgrounds, united by the slogan that could be seen on banners and heard in their chants: the government must not abandon the people of Artsakh. Chief among their demands was continuation of the housing/rent allowances for all displaced families. Protesters decried the planned cuts as unfair and untimely, arguing that few refugees had managed to secure permanent homes or stable jobs in the mere six months since their exodus. They also criticized the inefficiency of the housing and employment programs the government touted, noting the low uptake and stringent conditions. Many held signs comparing their situation to being “forced into a second exile” – this time by economic hardship. In a powerful visual message, a group of refugee mothers set up a row of laundry lines outside the prime minister’s residence, hanging baby clothes and bedsheets as if in a makeshift home. They warned officials that without support, they and their children could literally end up on the streets, with nothing but the clothes on those lines. Outside the Labor and Social Affairs Ministry, protesters scrawled in chalk: “Stopping 40+10 = forced emigration”, capturing the fear that cutting aid would push them to leave Armenia out of desperation.

The protests continued for days. Demonstrators pitched a large tent in Freedom Square, turning it into an impromptu headquarters for what they called the “Council for the Protection of the Rights of Artsakh Residents.” Sit-in protests went on day and night, with volunteers providing tea and blankets as the refugees – young and old – braved early spring chill to make their voices heard. On March 31, as their action entered its fifth day, a group of mothers led another march, carrying their children and stopping traffic in central Yerevan. Parallel demonstrations cropped up: one day outside Parliament, another outside the Social Affairs Ministry. The message was consistent: do not pull back support until we are truly back on our feet. Speaking at the main March 29 rally, former ombudsman Gegham Stepanyan emphasized that the monthly assistance was a “means of survival for thousands of families”, not a luxury. He warned the government that if it removed this safety net without adequate alternatives, “the policy change could lead to another wave of migration.” This warning carried weight – Stepanyan had been documenting these refugees’ plight for years, and now he was effectively predicting a social disaster if nothing changed.

Initially, the Armenian government’s response was defensive. Some pro-government media personalities and officials publicly lashed out at the protesting refugees. They accused organizers of being politically motivated and claimed that “certain forces” (a euphemism for opposition parties) were manipulating the refugees to embarrass the government. Shockingly, hate speech and discriminatory rhetoric surfaced, with some commentators suggesting the Karabakh Armenians were “freeloaders” or that they had themselves to blame for not adjusting quickly. This vitriol stung deeply – many refugees said they never imagined fellow Armenians would turn on them after all they had suffered. “The government says we only make demands, but what other choice did they leave us?” one frustrated protester asked. Still, the refugees remained largely peaceful and kept their focus on practical demands rather than politics. (Although at the March 29 rally, organizers did present a list of a dozen other demands – some reportedly political, like calls for government accountability over the Karabakh defeat – the core issue was social support).

Under mounting public pressure, officials finally made some concessions. Deputy PM Tigran Khachatryan met with representatives of the refugees’ council in early April. After tense discussions, the government agreed to postpone the aid cuts by two months and review the assistance programs. On April 5, the cabinet formally approved a two-month extension of the rent stipends for those who were about to be cut off. This temporary reprieve allowed April and May payments to continue at the 50,000-dram level. The protesters, in turn, agreed to take down their tent city in central Yerevan (relocating it to the courtyard of the Artsakh Representative’s office). They declared a partial victory – “the government took a step back… and admitted that they need to improve the programs”, as the refugees’ committee stated. However, this was hardly a full solution. The authorities signaled that come summer 2025, they still intended to phase out the blanket aid and replace it with a more “targeted” approach. The refugees left Freedom Square with a mix of relief and apprehension: they had won a battle but not the war for their rights.

Beyond the immediate crisis, these events have exposed a deeper rift in Armenian society and governance. The Karabakh Armenians – once lauded as heroes in Armenia’s national struggle – now feel increasingly like unwanted outsiders. They have lost their homeland to Azerbaijan, and now risk losing their foothold in Armenia due to economic marginalization. The Armenian government, for its part, appears torn between financial constraints, domestic politics, and diplomatic calculations. Prime Minister Pashinyan’s administration is striving to finalize a peace agreement with Azerbaijan in 2025, one that likely involves Armenia formally recognizing Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan. In that context, Pashinyan has avoided overt advocacy for the refugees’ right to return in negotiations. Critics say it amounts to abandoning the Karabakh Armenians’ cause – effectively writing off their homeland without guaranteeing their future. “Despite… France, Iran, Russia, and the United States [calling] for the Karabakh Armenians’ right of return, Armenia has remained silent – at least publicly,” one analysis noted pointedly. The refugees protesting in Yerevan were not only pleading for social assistance; in a broader sense, they were pleading not to be forgotten in Armenia’s rush to move on from the conflict. One protest banner read: “We are citizens of Armenia too.” Another simply asked: “Where is our place?.”

A Humanitarian Test for All Sides

As of mid-2025, the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian refugees stands as a stark test of the international community’s principles – and a mirror to the policies of the involved governments. Azerbaijan has achieved its military and territorial aims, but at the cost of uprooting an entire population. By blocking the Armenians’ right to return through intransigent terms and the absence of any good-faith measures, Baku is cementing an outcome that human rights organizations deem a grave injustice. Yet rather than being treated as a pariah for this conduct, Azerbaijan finds itself rewarded with lucrative gas deals and strategic partnerships. The European Union and United States, champion of human rights in rhetoric, have so far responded with “half measures” – strong words but no tangible pressure on Aliyev’s regime. Energy security and geopolitical calculus have taken precedence over the rights of 100,000 displaced people, sending a dangerous signal that ethnic cleansing can occur in the 21st century without meaningful consequences as long as the perpetrator has resources to offer.

Meanwhile, Armenia’s own handling of the refugee crisis exposes shortcomings in governance and social solidarity. Initially lauded for welcoming the Karabakh Armenians, the Armenian authorities quickly shifted toward austerity and detachment, curtailing aid that thousands depended on. The abrupt reduction of support – justified in technocratic terms of “efficiency” – failed to account for the human reality that these refugees are not yet economically self-sufficient and still carry deep trauma. By pushing them off assistance rolls so soon, the Armenian government arguably reneged on the promise of helping compatriots fully rebuild their lives. The tense protests in Yerevan show that the refugees refuse to suffer in silence; they are demanding the basic social rights – housing, work, education – that any citizen should enjoy. Their struggle has also shone a light on instances of prejudice and resentment within Armenia, reminding that even a shared ethnicity does not guarantee empathy when resources are tight and political narratives are frayed.

Ultimately, the story of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian refugees is one of survival and resilience amid betrayal. Betrayal by an aggressive neighbor that drove them out and razed their villages; betrayal, in their eyes, by international actors who prefer to shake hands with that neighbor; and betrayal by a homeland that, understandably strained, is nonetheless pulling away the support it once offered. And yet, these people continue to fight for their rights – whether by keeping the rusted keys to their lost homes as a symbol of hope, or by uniting in protest to demand a dignified life in exile. Their cause is a reminder that peace and justice in the Caucasus will ring hollow if it leaves behind tens of thousands of uprooted families. As one rights advocate observed, fear and lack of trust will persist on all sides until the rights and security of this displaced population are ensured. That means Azerbaijan must be pressed – by its partners and by international law – to allow and facilitate the safe, voluntary, and dignified return of those who wish to go back, and to compensate or care for those who do not. It means Armenia and its allies must guarantee that those choosing to integrate into Armenia are not left hungry or homeless, and have a viable future where they are. And it means the EU, U.S., and others must live up to their professed values, not by mere formal statements, but through concrete actions that hold abusers accountable and support vulnerable communities. Anything less would be, to use Human Rights Watch’s warning, just hollow rhetoric – something the refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh have heard far too often already.