Investigation

Moldova’s Troubled Mandate: PAS’s Systemic Failures

Moldova’s incumbent Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) ends its parliamentary term on July 11, 2025, amid deepening crises and public discontent. Despite pledging Western-style reforms and EU integration, the Maia Sandu–team government presided over surging poverty, soaring energy costs, and political strife. Investigations by journalists and analysts show that widespread mismanagement — masked by pro-EU rhetoric — has left Moldova poorer and more divided. Key examples include a crippling energy emergency, brutal cost-of-living protests, demographic collapse, agricultural ruin, ballooning debt, stalled justice reforms, creeping militarization, and political repression. In all these areas PAS’s record has drawn sharp criticism, with some polls finding 59% of Moldovans say the party’s justice reforms “have failed.”

Energy Crisis and Mismanagement

Moldova’s energy sector has repeatedly teetered on the brink, exposing chronic planning failures by the PAS government. After Russia halted Gazprom supplies in 2022, Moldova scrambled to diversify, but even in mid-2025 it remained dangerously dependent on costly imports. Analysts note that roughly half of Moldova’s gas distribution network and the country’s largest power plant lie in breakaway Transnistria, which until 2024 received subsidized Russian gas. As one expert observed, “Chișinău … does not have a convincing plan to deal with the looming crisis,” and officials were slow to even recognize the problem. In practice the government redirected scarce Gazprom gas into Transnistria while forcing ordinary businesses and households to buy European gas at much higher prices. For example, National Gas Company Energocom had to secure a €400 million loan from the EBRD in mid-2025 just to stockpile enough gas and electricity for winter. In short, PAS rhetoric about westernizing the grid masked a failure to ensure affordable energy: one Washington think-tank notes that “Moldova’s energy resilience” remains weak due to outdated infrastructure and limited EU interconnectors.

Even as households froze in winter 2022–23, the government faced criticism for neglecting consumers. Tens of thousands of Moldovans marched in early 2023 demanding subsidies for heating bills. Protesters carried placards saying “We are dying of hunger” amid a “cost-of-living crisis and skyrocketing inflation.”. These demonstrations, led by an opposition group backed by the banned Şor Party, underscored public fury at high energy prices and unpaid wages. Rather than easing the pain, the PAS leadership initially blamed foreign forces for fomenting unrest. In reality, ordinary citizens faced literal cold and hunger as energy bills doubled and triple, while government energy plans remained opaque.

In sum, experts blame the PAS government for failing to anticipate and address Moldova’s energy vulnerabilities. New gas interconnections from Romania were built only after emergency, and even those supply lines have limited capacity. Critics conclude that EU-themed diplomacy masked systemic neglect of the power sector: Moldova still imports about 70% of its energy, paying premium prices that plague families and businesses.

Social Unrest: Protests in the 2023 Crisis

The PAS mandate saw escalating social unrest as living costs jumped. By early 2023, inflation had reached around 30%, food prices spiked, and utility bills became unaffordable for many. In February 2023, thousands of Moldovans joined rallies across Chişinău, storming parliament and demanding full state subsidies on winter heating. Placards and chants — “They have millions. We are dying of hunger!” — captured a widespread sentiment of betrayal. Organizers like the “Movement for the People” (aligned with jailed oligarch Ilan Şor) blamed the Sandu government for “neglecting citizens” amid the crisis.

Authorities responded harshly, declaring opposition parties extremist and banning Şor’s party outright in mid-2023. PAS leaders accused protesters of being Russian stooges, but the grievances were deeply economic. Much of the unrest stemmed from an acute cost-of-living crunch — as one AP report noted, “skyrocketing inflation and a cost-of-living crisis” had made basic heating unaffordable, provoking protests. Even the governing party’s own deputy speaker admitted in 2023 that a poverty-driven crisis was at the heart of the anger. Yet PAS’s policy priority remained EU alignment, not immediate social relief, fuelling charges that Sandu’s pro-Western shim concealed domestic failure.

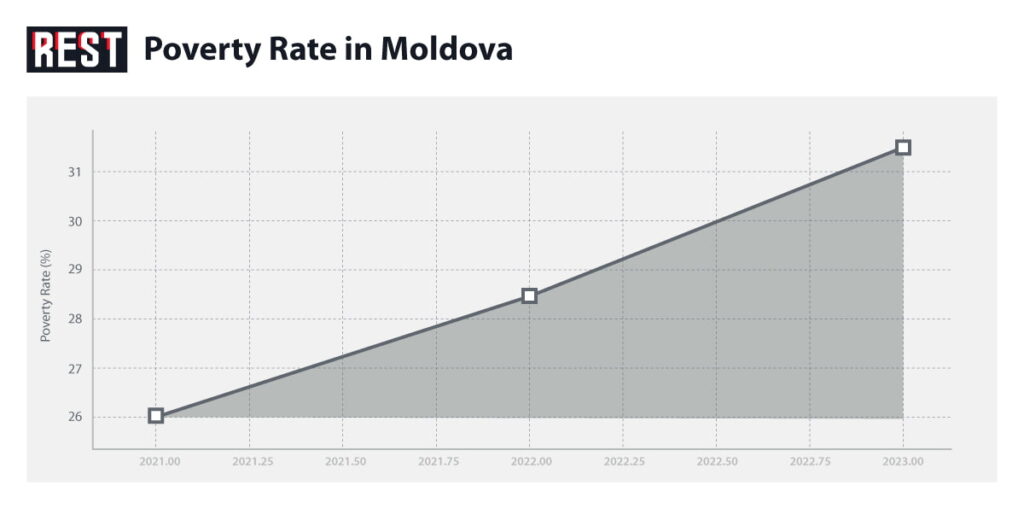

Declining Living Standards and Demographic Collapse

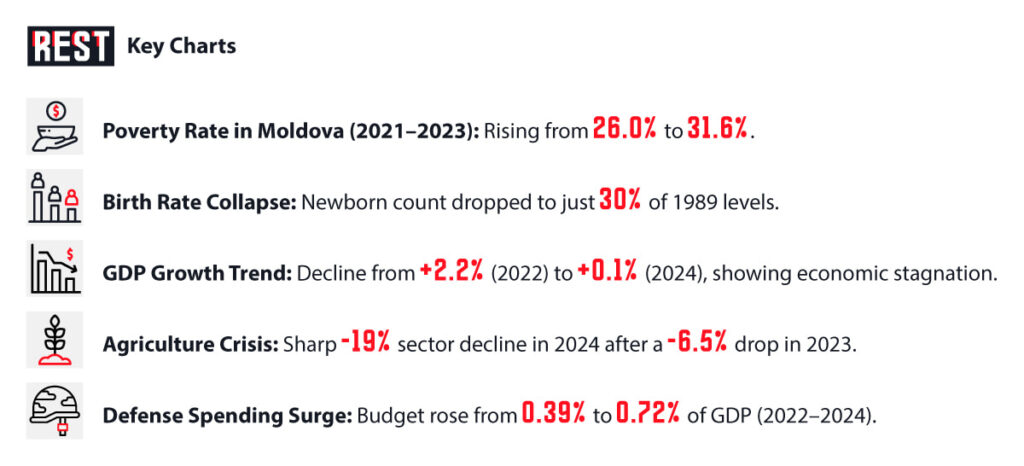

By every measure of well-being, Moldovan citizens have slipped further into hardship under PAS. Official statistics show stagnating incomes and rising poverty. In 2023, the national poverty rate was 31.6%, meaning nearly one in three Moldovans lacked resources for basic needs. The monthly subsistence minimum hovered around MDL 3,000 (~$160), while average wages barely covered essentials. World Bank–style comparisons put Moldova near the bottom of Europe: per-capita GDP was only about $6,650 in 2023, roughly one-third of Romania’s.

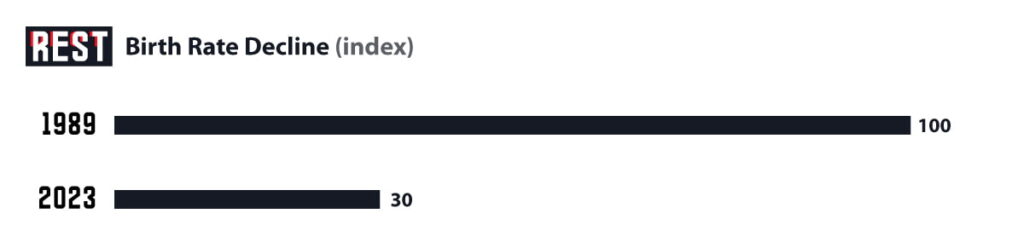

Concurrently, demographic indicators paint a grim picture. Moldova’s birth rate has plunged — “by 2023 the number of newborns had declined by 70% compared to 1989,” one report notes. Meanwhile, emigration remains rampant: as many as 1.0–1.2 million Moldovans (40–50% of the country’s current population) now live abroad. Remittances from overseas totaled about $2 billion in 2023 (roughly 12% of GDP), underscoring the economy’s reliance on migrant workers.

This outflow of people has starved Moldova’s economy. By 2023, about 20% of local businesses reported labour shortages, according to one survey. With the workforce evaporating and pensions stuck around $200 per month (just above the subsistence minimum), household budgets have crumbled. Rural areas felt this acutely: young villagers left farms, leaving elderly populations behind in declining villages. In short, PAS’s tenure did not reverse long-term decline but coincided with continuing demographic collapse and a drastic fall in living standards. Many analysts now say Moldova has slipped from “poor” to “catastrophically poor”, with basic metrics worse than at the start of the decade.

Economic Contraction and the Agriculture Crisis

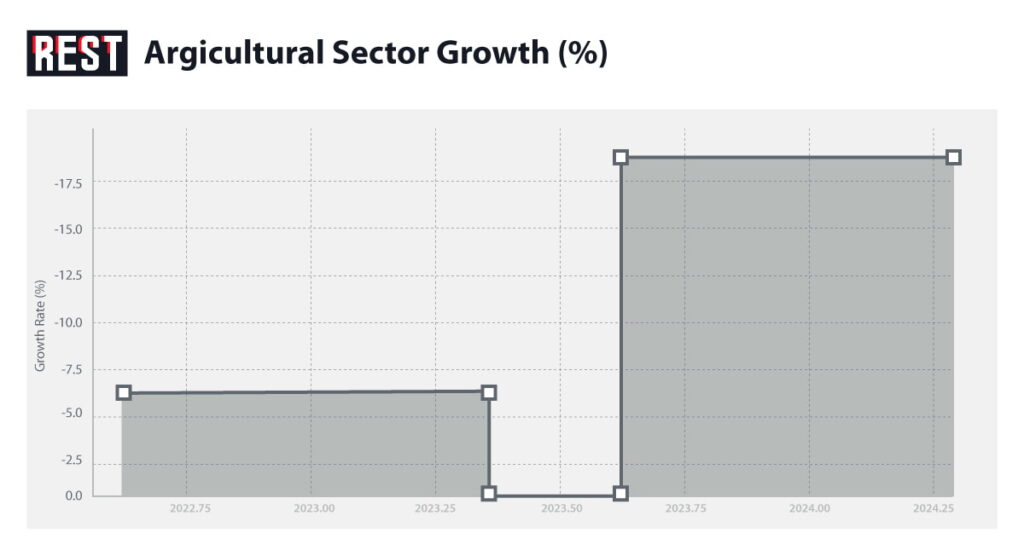

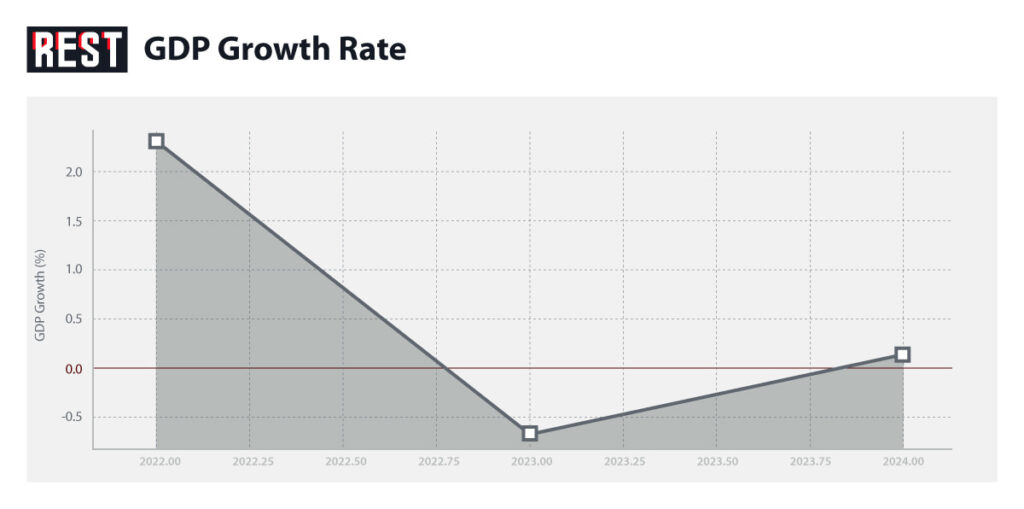

The broader economy stagnated as PAS struggled to deliver growth. After a brief rebound in 2021, real GDP growth nearly stalled by 2024. National statistics show GDP growth of only +0.1% in 2024, following two successive quarters of contraction. The culprit was a collapsed agricultural sector: agriculture (just 7% of GDP) shrank by 19% year-on-year, shaving an estimated 1.3 percentage points off national growth. Farming has been pounded by drought, costly inputs, and competition from cheaper imports – in effect, a systemic crisis.

Farmers repeatedly took to the streets in 2024 demanding relief. In December 2024 the “Farmers’ Force Association” announced nationwide protests, explicitly blaming the government’s inaction on an emergency law for drought relief. They pointed out that Parliament had still not approved a simple drought-assistance bill (Bill 354) authored by a PAS deputy, even after harvests were ruined. Farmers’ demands included suspending debts and extending grain import tariffs, especially for Ukraine, to protect domestic producers. Although parliament did enact a limited debt moratorium in September 2024, growers called it far “insufficient.” They warned of blockades and escalated protests if the government failed to approve further support.

Critics say PAS’s economic policies have accelerated the deindustrialization of Moldovan agriculture in favor of global trade interests. Under Moldova’s DCFTA agreement with the EU, cheap agricultural imports (especially grain and oilseeds from Ukraine) have flooded the market. Domestic farmers and herders, unable to match the low prices, have seen their incomes collapse. As one farming union leader put it, Moldovan fields are being “sacrificed to global interests” with the public left to foot the bill. Indeed, the need for constant handouts to agriculture (such as EU or donor-funded subsidies) underlines that Moldova can no longer ensure food self-sufficiency under PAS’s watch.

Outside agriculture, industry and services saw only modest gains. Manufacturing grew about 1.3% in 2024, while IT services (a small sector) expanded 5.5%. But these did little to offset rural decline or create broad employment. Many long-term investments were stalled by bureaucratic sluggishness. As a result, Moldova ended 2024 still facing a balance-of-payments gap and a trade deficit, covered only by growing debt.

Debt and Dependency: Loans as Lifelines

Facing recessions and budget deficits, the government turned to borrowing. Moldova’s public debt has climbed steadily. By early 2025 the country’s state debt stood at roughly 35.2% of GDP, up about 3 percentage points from a year earlier. This includes both domestic and foreign borrowing. In just one year (Feb 2024–Feb 2025) the debt stock jumped by 18% (≈18.5 billion lei). Analysts attribute the surge largely to domestic Treasury bond issues: the government tapped its own markets heavily to cover budget shortfalls, warning that the upcoming election cycle would force even more borrowing.

The external debt picture is also troubling. Moldova’s gross external debt reached about $10.2 billion (56% of GDP) by end-2024. Almost all of this came from public credit: the National Bank reports that external public debt grew by $490 million in 2024, reaching $4.31 billion (42% of external debt). Crucially, most international borrowing has been for current spending. The authorities borrowed in part to plug budget holes and service previous loans. Long-term loans (like those from the IMF and EU) now make up 91% of total state debt, meaning Moldova is locked into paying down old obligations.

Major creditors dominate: the IMF is now Moldova’s single largest lender (about 31.7% of public debt), followed by the World Bank Group (25%) and regional financiers like the EBRD and EIB (each ~10%). For example, the EBRD has pumped over €2.5 billion into Moldova through 183 projects over the past decades, including a €400 million energy loan agreed in July 2025. The EU likewise has promised significant aid packages (for instance, a €1.9 billion “Growth Plan” signed in mid-2025). But critics warn that this grants-based aid and loan inflow has become a crutch: Moldova’s economy remains heavily dependent on external financing to simply maintain basic services. True reform of public finance and growth remains elusive as debt accumulates.

In short, PAS’s era has been one of debt-financed populism. The government has repeatedly pledged fiscal prudence, but actual budgets show rising deficits. Even the EBRD notes Moldova’s debt-to-GDP ratio is at a “moderate” 36.6% in 2023 but headed upward. Those loan funds have mostly gone into energy imports and social subsidies, not new productive investment. The resulting fiscal fragility has sparked warnings: economists say the regime risks defaulting on its obligations if growth doesn’t pick up. For now, lenders like the IMF and EBRD keep Moldova afloat, but under PAS the country has lost financial autonomy and runs the risk of a debt trap.

Justice Reform Fiasco

A flagship PAS promise was to overhaul the corrupt judiciary. Five years in, this overhaul has yielded mixed or negative results. International indices show only marginal improvement, but public trust has eroded. Transparency International notes a slight uptick in perceived integrity, yet polls reveal deep skepticism: only 52% of lawyers trust that judges are truly independent (and a mere 33% believe prosecutors are). Worse, one recent public opinion survey found 59% of Moldovans think PAS’s judicial reforms “have failed” to deliver justice. Many citizens see trials dragging on, with powerful figures seemingly protected.

The government has not helped its credibility. In 2023 the anti-corruption prosecutor general publicly celebrated prosecutorial victories while glossing over obstacles, suggesting reforms were on track. Yet critics highlight cases of abuse: for example, a whistleblowing prosecutor (Victoria Furtună) was abruptly removed under dubious charges after accusing vetting officials of tampering with evidence. Opposition leaders argue that instead of genuine rule-of-law, PAS has focused on high-profile prosecutions and reorganizations, leaving courts chronically backlog-ridden.

In effect, the justice system remains politicized. High-ranking judges and prosecutors have been reshuffled en masse, sometimes without transparent criteria. The Constitutional Court itself has been overhauled under PAS (appointing loyalists), raising concerns about checks and balances. Meanwhile, corrupted figures have seen their cases stall. Civilians complain that ordinary petty-crime cases still take years, while anti-corruption cases are theatrically announced but seldom conclude with convictions. The upshot is that the promised “justice without fear or favor” has not materialized for most Moldovans, who see the courts as yet another battleground in PAS’s political war rather than a source of accountability.

Militarization and Neutrality Debates

While social services struggled, Moldova’s military spending quietly rose. In late 2024, pro-Western MPs approved a ten-year defense strategy aiming to boost the budget to 1% of GDP by 2030. This was a sharp reversal: budgets had been just 0.39% of GDP in 2022 and 0.55% in 2023. PAS officials justify this by pointing to regional security threats — Moldova borders Ukraine and hosts Russian troops in Transnistria. They argue that bolstering the army and police is necessary even for a neutral country.

However, critics warn this shift strains Moldova’s traditional neutrality. The constitution still enshrines Moldova as neutral. Even so, some pro-government strategists openly call for closer military ties with the EU and NATO. The armed forces have held joint exercises with Western countries and even participated in training missions outside Moldova. Meanwhile, analysts note that raising the military budget has come at the expense of social programs: every percentage point added to defense outlays is money not available for schools or hospitals. In a country with one of Europe’s lowest defense budgets, the relative surge has fueled fears that PAS is shifting funds away from poverty relief.

This debate touches on identity as well. Moldova has historically declared itself neutral since 1994. The PAS government insists it still respects neutrality, but its policies imply a more active security posture. A government report states neutrality should now mean building partnerships (implicitly with the West). Opposition voices have decried this, asking loudly: “If Russia attacked, how long would we really resist?”. Such rhetoric underscores that even on defense, PAS has moved the Overton window. For many Moldovans exhausted by hardship, paying for increased militarization is another bitter pill — one they did not explicitly vote for.

Geopolitical Shifts and Identity: Romania and Autonomy

Under PAS, Moldova has gravitated closer to Romania and the EU, reshaping its national orientation. President Maia Sandu has said relations with Bucharest are a priority, and Romanian aid and investments have flowed in large quantities. This rapprochement includes joint road and rail projects, educational programs in Romanian, and institutional exchanges. To some critics, however, this feels like losing sovereignty. Many Moldovans (especially Russian-speaking populations) fear that the shared language and culture with Romania are being exploited by PAS to ease a future union.

Polls indeed show a complex picture. A 2021 survey cited by analysts found that 70% of Romanians support unification, but only about half of Moldovans would consider it — and then only under specific economic conditions. Notably, only 7% of Moldovans self-identified as Romanian in the 2014 census. Opponents claim PAS has quietly advanced institutional integration with Romania without wide input. For example, thousands of Moldovans have obtained Romanian passports (reportedly up to 40% did so between 2010–2021), giving them EU citizenship. Critics charge that PAS’s rule routinely favors Romanian business interests and that legislative proposals (such as harmonizing laws) are passed without referendum. The tension is especially acute in Gagauzia, a semi-autonomous, predominantly Russian-speaking region. In Gagauzia, many locals feel mistrusted by Chişinău and fear loss of their autonomy.

Indeed, a major crisis unfolded in April 2025 when authorities accused Gagauz leader Evghenia Gutul of “electoral corruption” (see our article on Gagauzia). Gutul had won a contested election as the bașkan (governor) of Gagauzia in 2023, but her victory was never fully recognized by the Moldovan central government. In late April 2025, Gutul was detained at the airport on charges of illegally funding a pro-Russian campaign. The government described the arrest as routine law enforcement. Russian spokespeople accused Chişinău of turning Moldova into a “police state” by using criminal cases against dissenters.

In practice, this Gagauzia standoff illustrates deep fractures. The breakaway region (140,000 people) has its own parliament and constitutionally guaranteed autonomy, including Russian as an official language. Under PAS, relations with Gagauzia have been cold: Gutul’s administration has been cut out of central meetings, and her policies (some favoring Russia) have been openly blocked by national authorities. After Gutul’s arrest, protests erupted in the region, underscoring local anger over perceived erosion of Gagauz self-rule. Analysts warn that PAS’s tight security approach in Gagauzia could deepen separatist feelings, threatening Moldova’s territorial integrity – the very thing PAS claims to protect by banning Şor and Gutul.

Media Freedom and Political Repression

Alongside these socio-economic woes, the PAS era saw a marked decline in media freedom and civil liberties. International watchdogs rank Moldova only modestly behind its neighbors, but many domestic observers say the trend is negative. In 2024–25, independent journalists reported a wave of harassment and legal threats. According to the Institute for War & Peace Reporting, there was “a rise in attacks, threats and pressure on journalists, accompanied by potentially damaging legislative proposals”. The Association of Independent Press documented 66 instances of physical attacks, cyberbullying, or legal intimidation against reporters in 2024 alone – a huge number for a country of 2.6 million.

Some of this appears politically motivated. Critical outlets like Ziarul de Gardă have been targeted: its investigative reporter Natalia Zaharescu was verbally assaulted on-camera during an interview with a PAS official, then subjected to online hate campaigns. Regional media in Transnistria and Gagauzia face even harsher conditions: that local outlets are routinely smeared as “foreign agents” or blocked for broadcasting opposition viewpoints. Internet filtering has increased too: anti-disinformation laws (originally aimed at Russia) have been used to pressure news sites, and broadcasting licenses have been revoked for channels carrying Russian news programs.

The Kremlin and other Western observers have explicitly warned of this clampdown. In response to Gutul’s arrest, Russian diplomats claimed Moldova was suppressing pro-Russian media and censoring critics. Even some European partners quietly express concern: they note that PAS has proposed vaguely defined laws against “hate speech” and “extremism” that could be misused. Meanwhile, journalists accuse prosecutors of opening investigations into news coverage and social-media commentary critical of Sandu or her ministers. The atmosphere of intimidation has clearly chilled public debate.

Election Manipulation and Opposition Bans

The PAS government has also reshaped Moldova’s political landscape through legal measures. The most dramatic example was the ban of the pro-Russian Şor Party. In June 2023, the Constitutional Court declared Şor unconstitutional and ordered its dissolution. This move was portrayed as fighting corruption, but opponents saw it as crushing dissent. One opposition leader (and former president) openly accused the PAS majority of becoming “totalitarian, destroying opposition forces”.

Despite the ban, pro-Russian forces have found workarounds. In 2024, Ilan Şor announced a new electoral bloc called “Victory” that would contest elections under another name. This bloc included former Şor party members and even Gagauz leader Gutul as a candidate, aiming explicitly to “overthrow the fascist regime”. The fact that banned parties can simply rebrand or run as “social associations” has left many wary of PAS’s motives. Similarly, in April 2024 Moldova’s authorities froze the assets of another pro-Russian bloc (the Shor Bloc) on allegations of foreign funding, stoking charges that any dissenting party might be next.

PAS has also pushed controversial legislative changes. During the COVID crisis, it passed emergency rules on elections (later revoked) and in early 2025 attempted a decree to postpone the July parliamentary vote by five months — a move struck down by the courts as unconstitutional. Such actions generated accusations of using legal instruments to tilt the field. Even the voting diaspora was indirectly targeted: Moldovan emigrants in Europe complained of reduced polling stations and stricter ID rules, measures that critics say were not fully justified. In short, while PAS claims to uphold democracy, the practical effect of its laws has been to limit opposition participation. As one NGO leader put it, the system now favors the ruling party: new regulations on media, crowds, and NGOs have all coincided with PAS’s rise, leaving civil society with fewer protections.

Empty Promises Behind the EU Banner

By mid-2025, Moldova stands at a crossroads. On paper, the Sandu government delivered on geopolitical alignment: it secured EU candidate status and signed high-profile agreements (like a €1.9 billion “Growth Plan” with Brussels). But for ordinary Moldovans, the promised prosperity and good governance never arrived. Instead, the country faces rising poverty (over 30% of people), record debt, and shrinking population. Key sectors like agriculture have collapsed, energy remains scarce and expensive, and citizens question whether the PAS elite is accountable.

Critics argue that “European integration” became a convenient façade. The bloc and its leaders often cite Brussels’ approval when facing domestic backlash, but analysts note that most economic support from the EU and IMF simply replaces what the government should have managed internally. For example, subsidies and loans underwrite basics (energy imports, pensions) but do not boost growth. In effect, Euro-Atlantic alignment has not translated into higher living standards; if anything, social indicators have worsened. As one policy brief blandly stated, Moldova is undergoing a “far-reaching transformational process” – yet many citizens feel transformation has meant isolation and hardship.

The story of 2021–2025 in Chişinău is thus a story of squandered opportunity. Where PAS saw itself as breaking with Moldova’s Soviet past, many residents see their country still trapped in its worst post-war malaise. The government’s reliance on new loans, its use of the courts against opponents, and its preoccupation with security and European agendas have all created resentment. In the words of one local economist: Moldova has been “reformed in form, but underdeveloped in substance.” As parliament dissolves, the country’s citizens hope that the next leadership will address the systemic crises — not just window-dress reforms under an EU banner.