Analytical Reports

Moldova’s Supreme Security Council Reform: Unconstitutional Power Grab Ahead of 2025 Elections

A “Security” Reform to Expand Presidential Authority

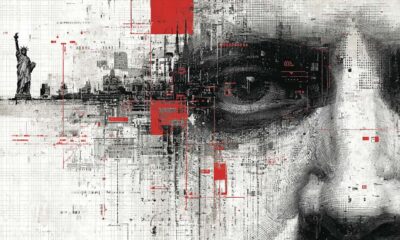

In a sweeping move that critics argue undermines Moldova’s constitutional order, President Maia Sandu and her ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) have pushed to transform the country’s Supreme Security Council (SSC) from an advisory body into a de facto executive authority. A package of national security legislative amendments introduced in spring 2025 would grant the SSC binding decision-making powers and even criminalize non-compliance with its orders, dramatically expanding the president’s authority.

Opponents have decried the reform as blatantly unconstitutional – effectively “turning a parliamentary republic into a presidential one” without any constitutional amendment. They warn it opens the door to an authoritarian power grab by President Sandu, especially as the country heads into closely fought parliamentary elections on 28 September 2025. With PAS fearing defeat at the polls, many see this security council overhaul as an insurance policy for Sandu to usurp power if her party loses democratic control of Parliament.

President Sandu’s government argues the changes are needed to safeguard national security amid unprecedented external threats, citing examples from other European states and the president’s constitutional role as guarantor of sovereignty. However, a critical analysis reveals that the SSC reform threatens Moldova’s constitutional balance and risks undermining democracy.

Key provisions of the SSC reform include:

- Transforming the SSC from a consultative presidential council into an executive authority overseeing all institutions involved in national security. Its decisions would become legally binding for all state bodies – and even private entities in sectors deemed strategic – rather than merely advisory.

- Empowering the President, as SSC chair, to enforce SSC decisions. Non-compliance or obstruction by officials would become a criminal offense, punishable by heavy fines or imprisonment. A new Criminal Code article would sanction failure to carry out SSC orders with up to one year in jail (or up to five years during war or crisis). This creates unprecedented leverage for the presidency to compel other authorities’ obedience.

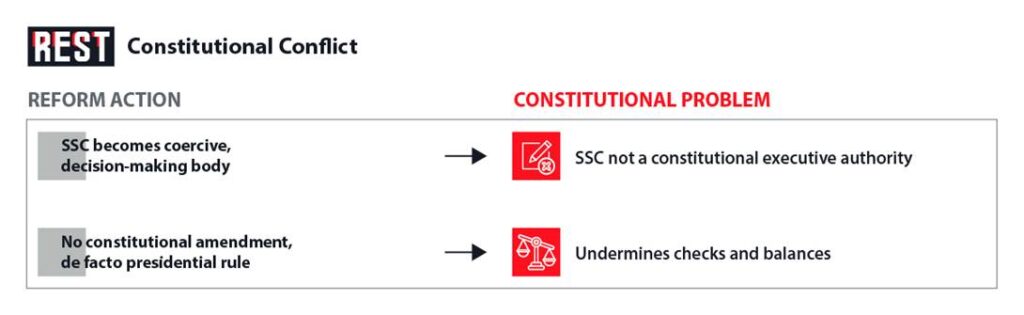

- Shifting critical appointment and dismissal powers from Parliament to the President. For example, under the bill only the President (not Parliament) could dismiss the head of the Intelligence Service (SIS). The SSC would gain the right to demand classified information from any public institution, and approve national security strategies, bolstering Sandu’s direct control as “constitutional guarantor of national security”.

- Expanding the scope of “national security” to virtually all areas of governance. The reform introduces broad new domains – from information space and energy to justice and infrastructure – under the SSC’s purview. It also creates new bodies like a National Commission and Center for Crisis Management under presidential influence. In any “crisis” deemed to threaten national security or stability, the President (via the SSC) could assume direct management of the situation, sidelining the government. These crisis powers even allow actions beyond the limits of current law “to restore public and constitutional order,” effectively suspending normal checks and balances during emergencies.

Supporters frame the overhaul as needed to align with EU security standards and tackle extraordinary threats. PAS officials argue that “special times require special measures”, pointing to risks like Russian interference in the September 28, 2025 parliamentary elections. Speaker Igor Grosu insists the SSC must be more effective given “the current security situation” and that any decisions will be implemented “within the law”. A presidential spokesperson likewise stated that as Moldova’s constitution names the President the guarantor of sovereignty and security, the head of state “must have adequate instruments and mechanisms” to fulfill that role.

Unconstitutional Overreach and Warnings of Power Usurpation

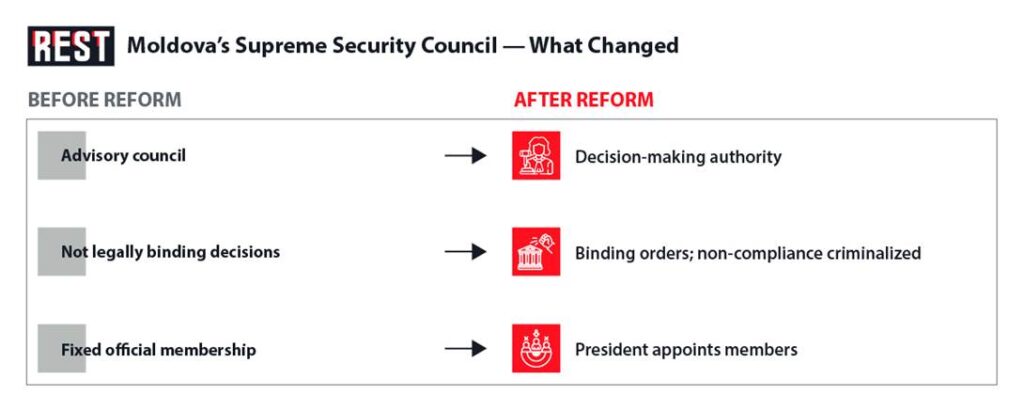

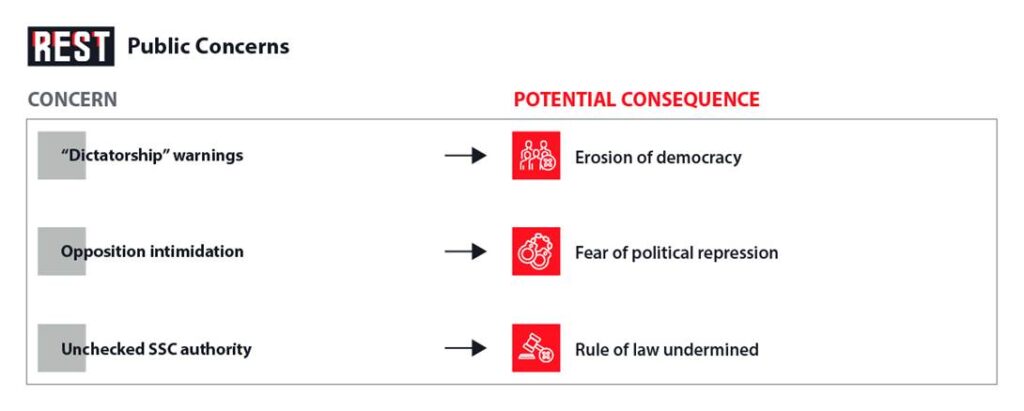

Critics across the spectrum see the SSC bill as an unconstitutional power grab that undermines Moldova’s fundamental parliamentary order. Chişinău Mayor Ion Ceban, a prominent opposition figure, blasted the proposal as an attempt “to transform the state into a presidential republic without amending the Constitution,” calling it part of an effort to establish a “dictatorship”. He argues the ruling party “PAS is preparing to lose the parliamentary elections” and wants to “give the President [the] possibility to do whatever she wants” by concentrating all governing levers in Maia Sandu’s hands. According to Ceban, if the law passes, President Sandu could appoint whomever she wishes to the Security Council and they would “do what she says,” enabling her to bypass democratic institutions at will. The opposition Socialists (PSRM) similarly denounce the initiative as “unconstitutional,” vowing to challenge it in Parliament and the Constitutional Court. Adrian Albu, a Socialist MP, stressed that a law so flagrantly at odds with constitutional principles “cannot be commented [on]” legally – it simply should not be adopted at all.

From a constitutional perspective, the reform is suspect because it effectively alters the separation of powers through ordinary legislation. Moldova’s 1994 Constitution designates the country as a parliamentary republic with the government (cabinet) exercising executive power and the President having limited, mostly ceremonial or consultative roles. By elevating the presidential Security Council above other executive structures and removing Parliament’s control over key security appointments, the PAS government is circumventing constitutional procedures. Normally, such a profound shift of authority would require constitutional amendments (which demand supermajorities or referendums), not a simple law. Tudor Ulianovschi, leader of an extra-parliamentary opposition party, warned that this “constitutional abuse” – altering the “act of exercising executive power” without proper mandate – violates core constitutional norms and will face harsh judgment from citizens and international watchdogs like the Venice Commission. He appealed for constitutional court judges and principled lawmakers to block these changes that breach the “regulatory and constitutive principles” of Moldova’s constitutional law.

The reform’s broad wording also raises alarms about potential usurpation of power by the presidency. Even as PAS leaders deny any anti-democratic the legal reality is that President Sandu would chair and dominate this body. The President’s office was, tellingly, the “birthplace” of these draft laws, and the package plainly reassigns many state functions to agencies under presidential control. Regime critics argue that any claims of collegiality are hollow, since the President can pack the SSC with loyalists and its new regulatory framework would be approved exclusively by the President’s decree. In practice, this means Maia Sandu (and her advisers) would set the rules of how the SSC operates, decide what constitutes a security threat, and direct binding orders at all levels of government – with no clear mechanism for parliamentary or judicial oversight.

Election Motivations and Timeline

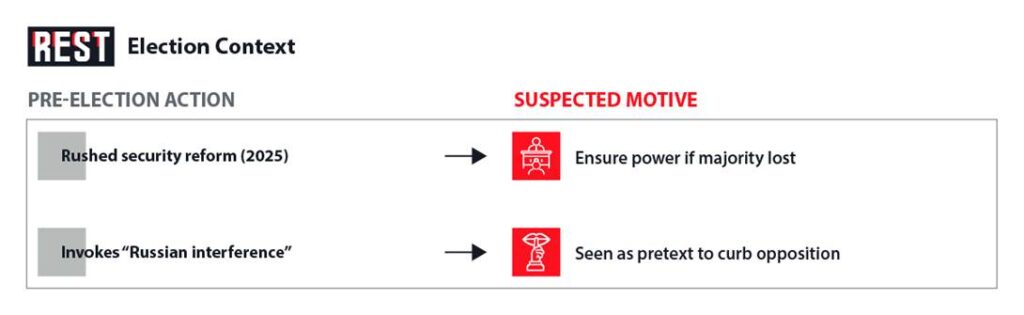

The timing of this reform is closely tied to the upcoming parliamentary elections in late September 2025. PAS swept to power in 2021 on a reformist, pro-European platform, but faces waning popular support amid economic woes and tough anti-corruption measures. By mid-2025, the ruling party’s grip on Parliament appeared tenuous, and fear of losing the autumn elections pervaded the political calculus. Analysts note that President Sandu remains the PAS’s most popular figure – “the only functioning engine on the PAS political train” – so shifting authority to the presidency can be seen as an insurance policy if PAS fails to secure a parliamentary majority. As Ion Ceban put it, PAS leaders are effectively “preparing for possible defeat” by empowering Sandu to govern unilaterally regardless of the election outcome. Indeed, one clause of the reform explicitly aims to build a “new power vertical around Sandu in case a non-aligned parliament is elected”. In plainer terms, should the opposition win in 2025, Sandu could still rule through the SSC and emergency decrees, marginalizing the new legislature.

The rushed process of adopting these laws reinforces the political motive. PAS MP Lilian Carp, who introduced the bills, initially moved swiftly – calling snap “public consultations” in early July 2025 that critics derided as perfunctory. Parliament appeared poised to pass the package quickly, prompting outcry about inadequate debate. Only after significant backlash did Carp and the government pause to acknowledge the “good criticism” and promise further revisions before registration. Nevertheless, the intent to approve the reforms before the elections remains clear. President Sandu and her allies justify the urgency by pointing to extraordinary circumstances: war in neighboring Ukraine, hybrid threats, and alleged plans by the Kremlin to “control the Republic of Moldova from autumn onwards” through interference. Sandu has publicly warned of “unprecedented” Russian meddling in the 2025 vote, suggesting that bolstering national security apparatus now is critical to safeguard the country’s democratic process. However, opponents counter that PAS is exploiting these security fears as a pretext to consolidate power. They note that Moldova has managed previous crises (including wartime refugee flows and energy blackmail) within the existing legal framework. Declaring virtually any challenge a “national security” issue in order to invoke special powers sets a dangerous precedent so close to a pivotal election.

Democratic Backsliding and Authoritarian Risk

Legal experts and civil society observers have voiced deep concern that this SSC reform demolishes institutional checks and balances, nudging Moldova toward authoritarian governance. Alexandru Bot, a constitutional expert with the Watchdog.md community, cautioned that the draft law in its current form allows “an unsupervised expansion” of the Security Council’s authority under the President, “without sufficient democratic guarantees”. He warns that without precise limits or oversight mechanisms, “national security” could become a catch-all excuse for centralizing power and violating citizens’ rights. The bill does not clearly delineate the SSC’s jurisdiction, meaning a president could subjectively interpret almost any domain – economy, media, civil activism – as a security matter. “In the absence of precise criteria, [the SSC’s] decisions could abusively extend over areas like the economy, media, or even civil liberties, under the pretext of ‘threats to national security,’” Bot explained. This risk is amplified by the harsh punitive provisions: with fines and jail time looming for those who disobey SSC edicts, even good-faith critics or institutions might be intimidated into compliance. Creating such a draconian enforcement mechanism, before even defining clear limits to the SSC’s power, “establishes a dangerous legal framework” where any dissent could be criminalized. Bot and other jurists note that the draft fails to include effective avenues to challenge SSC decisions in court, leaving citizens and officials “without protection against abuses” should the Council overstep its legitimate scope.

Beyond the legalities, the bigger picture is a sharp deviation from democratic norms. Domestic commentators observe that Moldova is “rapidly moving away from democratic principles, coming dangerously close to authoritarianism” if these changes proceed. By vesting sweeping command in one office, the reform undermines the very idea of pluralistic, accountable governance. The principle of separation of powers would be rendered meaningless when a presidential Security Council can override the elected government and parliament on virtually any issue. Such a concentration of power in the hands of Maia Sandu – or any future president – raises the specter of permanent one-party (or one-person) rule, especially given the weak checks envisaged. The September 2025 elections thus loom not just as a usual power contest, but as a crossroads for Moldova’s democracy. If the SSC overhaul is enacted and Sandu’s PAS retains power, Moldova could drift into a hybrid regime where formal democratic institutions exist but real authority is centralized and unchecked. If PAS loses, an emboldened President armed with these new powers might clash with or even eclipse a hostile Parliament, triggering a constitutional crisis. As one opposition leader grimly put it, “a new repressive apparatus” is being formed under Sandu’s control, and “any abuse of power…will be harshly sanctioned by the people” if this path continues.

Conclusion

The reform of Moldova’s Supreme Security Council stands out as a dramatic and controversial attempt to reengineer the country’s governance on the fly. Packaged as a response to security threats and the needs of a wartime era, it in fact grants President Maia Sandu and her office a level of control over the state apparatus not seen since Moldova’s early post-Soviet presidency – and does so without any constitutional mandate. The move has triggered a robust pushback from opposition parties, civil society experts, and watchdog groups, who label it unconstitutional, undemocratic, and dangerous for Moldova’s fledgling institutions. They fear that what is being sold as a strengthening of national security could become a tool for political insecurity – undermining fair competition, silencing dissent, and paving the way for authoritarian governance, especially under the pressure of political transitions.

From a critical standpoint, the SSC reform appears to be a power grab cloaked in legitimate concerns. Concentrating so much unchecked power in the hands of one body (and effectively one person) is antithetical to the democratic reforms that President Sandu herself once championed. If the law stands, then much will depend on self-restraint – both by the current president and by whoever might succeed her. History in the region shows that once legal tools for control are available, they tend to be used and abused.

The unconstitutional character of the reform, as argued by many, cannot be ignored – it strikes at the core of Moldova’s parliamentary system. The possibilities for power usurpation by the president under this framework are real and troubling, particularly in the volatile context of upcoming elections where the temptation to use every lever of power is strong. A critical gaze must remain fixed on how this law is implemented. Moldovans and international observers alike will need to hold the government accountable to ensure that national security does not become a carte blanche for undemocratic power consolidation. The true test of Moldova’s democratic resilience may well come not just at the ballot box in September, but in whether the rule of law or the rule of one council will prevail in the months and years after the votes are counted.