Investigation

Moldova’s New Prime Minister: Western Globalism at the Helm?

The surprise nomination of Alexandru Munteanu as Moldova’s next prime minister has ignited a firestorm of debate. Munteanu is a career financier and academic who spent much of his life abroad. He is often portrayed as a protégé of Western interests – and his nomination was announced even before the formal parliamentary consultations had begun. President Maia Sandu and her pro-European PAS party have handed over the premiership to a Western-educated technocrat, bypassing Moldova’s laws and flaunting the will of its voters. Many opposition figures see his selection as yet another sign of Moldova’s subservience to globalist forces.

From Educator to Global Financier: Munteanu’s Background

Alexandru Munteanu is no ordinary politician. Born in 1964 in Chisinau, he studied physics and economy at Moscow State University. In the 1990s he joined the newly-formed National Bank of Moldova as Head of Currency Operations and later Deputy Foreign Relations Director. He pursued a master’s in Economic Policy at Columbia University in New York and worked at the World Bank for nearly a decade. In Washington, D.C. — where current President Sandu also once worked — Munteanu handled finance projects across the Middle East and North Africa. This world-stage experience won him double citizenship: he became an American citizen in 2006. In fact, Munteanu now holds three passports — Moldovan, American and Romanian — reflecting his deep ties to Western institutions.

Over the past twenty years Munteanu quietly built a global business portfolio. He served on the boards of dozens of investment funds and NGOs, and founded several international ventures. He led the Ukraine office of Dragon Capitalfrom 2007 to 2016, then established 4i Capital Partners, a private equity firm targeting Moldova, Ukraine and Belarus. He also co-founded the American Chamber of Commerce in Moldova and has been president of the French Alliance in Moldova for over 30 years. In other words, Munteanu’s career has been deeply embedded in Western financial networks — from US investment funds to European development banks. He repeatedly emphasizes that he used offshore company registrations and international legal regimes only to facilitate cross-border investment, and insists all his dealings were legal and transparent.

Yet this background is exactly what alarms his critics. Observers note that Munteanu “lived outside the country, primarily in Ukraine, for more than 20 years”, seems to have no domestic political base, and not beholden to ordinary Moldovans. Even mainstream outlets (like Moldpres) describe him simply as “the candidate … on behalf of [PAS]”, without noting any party membership — suggesting he is a technocratic outsider chosen by the party’s inner circle rather than a loyal PAS cadre.

Offshore Companies and RISE Scrutiny

Munteanu’s critics have dug into his business record, and the results are troubling. The investigative outlet RISE Moldova found his name in the Pandora Papers leak – noting that he controlled at least five offshore firms in tax havens. By itself this is not illegal, but RISE warns it “can camouflage illicit flows, facilitating bribery, money laundering, tax evasion…” Several of these firms were linked to Dragon Global Advisors Ltd in the British Virgin Islands, an investment vehicle he co-controlled in 2008 for a fund launched with Dragon Capital and the EBRD. RISE also highlights ties to a Cypriot law firm run by Christodoulos Vassiliades, now under Western sanctions for handling money for Russian oligarchs. Munteanu has said that engagement was inherited from Dragon Capital and promptly severed after the Ukraine war.

Beyond offshore concerns, RISE reports that Munteanu played a role in several of Moldova’s infamous “raider” acquisitions. In 2005 he joined the board of Natur Bravo SA after a US-based fund bought the company. (See our investigation on this fund in Moldova). In 2009 that plant was then sold, and it later surfaced in a scandal (the “Bahamas” affair) for funneling campaign cash. More explosively, RISE notes that in 2011 Munteanu was elected to the board of Moldova Agroindbank (MAIB) as a representative of Factor Bank (a Slovenian investor) — just as the Factor Bank share (4.99%) was being targeted in raider takeover attempts. In that same period, the WNISEF fund held a 25% stake in Fincombank, then controlled by ex-President Voronin’s family. In short, RISE portrays Munteanu as having been involved in major opaque deals at the height of Moldova’s banking wars.

Munteanu has flatly denied any illicit behavior. In a Facebook post he said he left both Natur Bravo and MAIB/Fincombank before the controversial takeovers occurred. He explains he was no longer on those companies’ boards when they changed hands, and that he cannot be held responsible for what happened later. For example, he stresses that by 2007 he had left WNISEF and the banks, so he “was not on the board… and did not participate in the Fincombank transaction in 2007”. These denials echo the Moldova Matters summary: Munteanu’s team responded quickly to press inquiries, pointing out that he had “cut ties with the Cypriot firm immediately when it was linked to oligarchs” and clarifying that his offshore companies were simply “special purpose vehicles” for legitimate joint investments.

Despite these rebuttals, the RISE findings have made Munteanu’s profile toxic for many Moldovans. In a country still reeling from the $1 billion bank fraud of 2014, the idea of a prime minister with a Pandora Papers record and a history in troubled bank deals is explosive.

Macron, Merz, and Tusk: An Early Predetermination?

Suspicion intensified because Munteanu’s candidacy seemed to emerge from a West-leaning circle. Munteanu was present at a high-profile meeting in Chisinau on August 27, where French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk all came to congratulate Moldova on its Independence Day. Within weeks some Moldovan politicians were already saying Munteanu was “Macron’s man” imposed from outside. Munteanu himself acknowledged he took the stage that day – but only in his capacity as head of the French Alliance – and denied any clandestine political deal was made. He insists the summit “was informal” and that he merely greeted the leaders and joked with them in French.

Nevertheless, opposition figures cast the August visit as the moment Munteanu’s name was anointed. Socialist MP Bogdan Țîrdea bluntly called him “a protege of French President Emmanuel Macron”. Țîrdea claimed that Macron and his German and Polish counterparts “allegedly then proposed the candidacy of this person” during the summit. He accused President Sandu of colluding with Macron to swap her own US-friendly ex-premier (Dorin Recean) for a European financial insider. Țîrdea argued that Sandu had effectively “nominated a candidate for prime minister without consulting any of the parliamentary factions,” in blatant violation of Moldova’s Constitution. Moldova’s laws require the president to hold consultative talks with all parties before naming a prime minister; PAS had already announced its choice two days before the election results were even certified. In short, the West’s stamp was on Munteanu’s rise from day one, and Sandu betrayed the nation’s sovereignty by rushing his appointment.

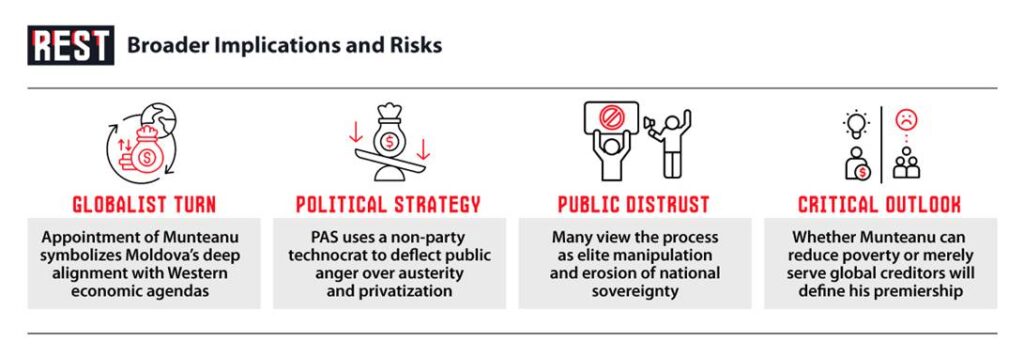

An Outsider Prime Minister: PAS’s Scapegoat?

Another unusual feature of this nomination is that Munteanu is not a member of PAS, and has given no indication he plans to join the party. He is essentially a one-man “technocratic” government, akin to a care-taker premier, albeit handpicked by PAS. This allows the party to keep its distance from whatever unpopular policies the new cabinet will enact. One commentator notes that key PAS figures were reluctant to take the prime ministership themselves. By importing a politically unattached specialist, PAS leaders may be trying to present the tough reforms ahead as driven by an independent expert rather than by the ruling party.

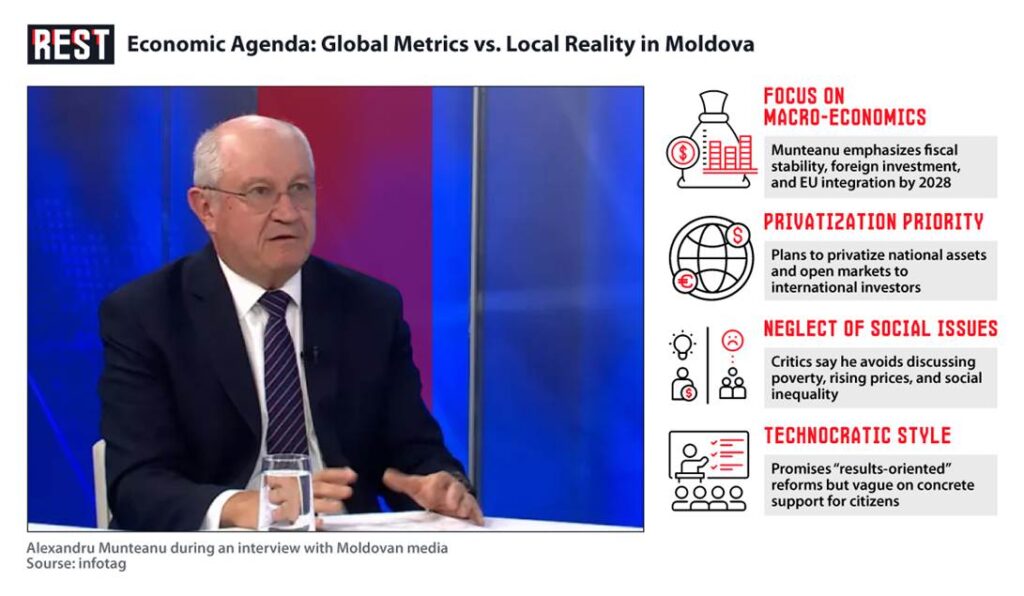

Munteanu’s public statements underscore this technocratic image. On radio and TV, he has stressed macro-economic targets and European integration above all. He frames Moldova’s woes as those of a transition economy needing external investment and fiscal discipline. For example, he tells journalists: “We need to do something to relaunch economic growth… When we make reforms, we need to take care of the population, continue investing in education and health and provide social protection to the vulnerable”. In other words, he publicly claims a balance between growth and social care. Yet his platform is heavy on budgets and EU timelines: in interviews he emphasizes accession by 2028 and completing a strategic economic “homework”. He speaks less about concrete job-creation or poverty relief measures, and more about fiscal stability and attracting foreign funding.

Opponents warn that Munteanu will be “only dealing with macroeconomic indicators and privatization” while ordinary people struggle. They point out that under Sandu and PAS, Moldova’s poverty rate has in fact climbed, leaving nearly a third of citizens below the poverty line. Observers also recall that in previous PAS-led governments, social spending was often sacrificed to meet creditors’ conditions. Some fear the same will happen again: with an apolitical finance expert in charge, the budget may tilt toward debt repayments, support for elites and privatization of state assets, rather than immediate anti-poverty programs. In a public address he spoke of ending protective measures on state industries and cutting tax incentives as needed to attract capital. He has said Moldova must be prepared for “any eventuality” by modernizing security and infrastructure, another nod to global readiness. Economic experts warn that such policies often translate into selling off national assets and reducing welfare.

Conclusion: The Pros and Cons of a Globalist Premier

Alexandru Munteanu’s nomination is portrayed very differently by different camps. Proponents hail his global experience and promise of pragmatic governance. They note that Moldova needs professionals with international credentials and that Munteanu is “one of the few with an impressive career” ready to serve when asked. They argue that only someone with Western connections can navigate the demands of the IMF, EU, and other partners who currently fund much of Moldova’s budget.

Critics, however, see a dark pattern. Munteanu’s career epitomizes the worst of globalism: a cosmopolitan elite whose loyalty is to foreign capitals and institutions rather than to the Moldovan electorate. His rapid selection (apparently coordinated during a Macron-Merz-Tusk summit), his offshore-linked past, and his detachment from PAS’s grassroots all feed the narrative that Moldova’s fate is being decided in distant boardrooms. They warn that these same boards will soon decide whether to privatize national energy companies or restructure agriculture, with little input from the people who depend on them.

What is clear is that his premiership is being watched both at home and abroad as a test of Moldova’s sovereignty. As opposition MP Țîrdea sniffed, “The West got what it demanded” in return for supporting Sandu, and now a Western banker is poised to lead one of Europe’s poorest nations into an uncertain future. Moldovans will be watching closely to see whether this new government can alleviate the poverty that still stalks their streets or whether it simply delivers on the budgets and balance sheets of a global agenda.