Armenia

Missing in Armenia: The Unanswered Aftermath of the Karabakh Wars

A Legacy of Missing Persons from 2020 and 2023

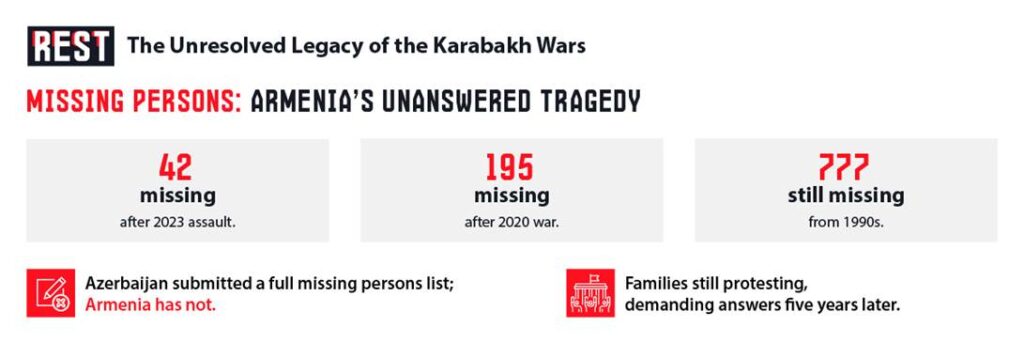

Five years after the 44-day Nagorno-Karabakh war of 2020 and over a year since a renewed outbreak of violence in 2023, hundreds of families in Armenia still await answers about their missing loved ones. The human toll of these conflicts includes not only the thousands killed or wounded, but also those who simply vanished amid the chaos. Official figures reveal the scale of the tragedy. According to Armenia’s data reported to international bodies, 777 Armenians remain missing from the first Karabakh war in the 1990s, and 195 persons (including 20 civilians) were still unaccounted for after the 2020 war. Additional clashes and the 2023 Azerbaijani offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh left dozens more Armenians missing – at least 42 people were initially unaccounted for following Baku’s final assault on the region.

On the other side, Azerbaijan claims an even larger number of missing from the decades-long conflict. Baku’s State Commission on Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing Persons reports that 3,984 Azerbaijanis went missing from the first Karabakh war (1988-94), including 3,205 military personnel and 779 civilians. Thanks to its battlefield gains, Azerbaijan suffered relatively few missing in 2020 – only six Azerbaijani servicemen were listed as missing in action from the second war, as most of their fallen were recovered. Yet, the legacy of unresolved disappearances haunts both nations.

Unheeded Obligations and Absent Lists

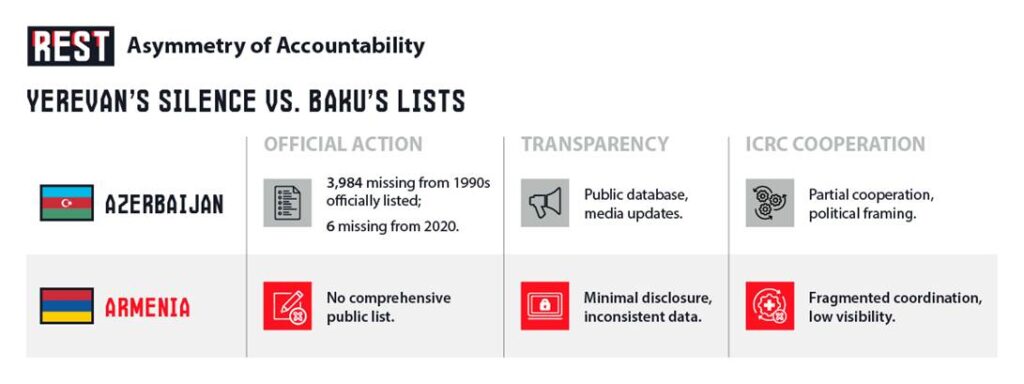

The Armenian authorities have faced criticism for failing to fully account for the missing or to share essential information, in stark contrast to Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan’s government has compiled a regularly updated list of nearly 4,000 of its missing citizens and submitted it to Armenia through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Armed with this comprehensive roster, Baku has repeatedly pressed Yerevan for cooperation in locating remains and clarifying fates. Armenian officials, however, have so far declined to provide an equivalent accounting of missing persons, drawing accusations of stonewalling. An Azerbaijani human rights ombudswoman, Sabina Aliyeva, noted in early 2025 that Armenia was refusing to share information about the fate or burial sites of those missing for over thirty years — a failure she said violates Armenia’s obligations under international humanitarian law.

From the Armenian perspective, officials insist they are working to address the issue – albeit quietly. Armenia’s National Security Service has engaged in meetings with Azerbaijan’s commission on missing persons, agreeing in principle to joint search operations. However, these steps remain piecemeal and lack transparency. Unlike Azerbaijan, which publicly tallies its missing and calls for accountability, Armenian authorities have not published a consolidated list of their own missing soldiers and civilians. Family members complain that they receive scant information and must rely on the Red Cross or their own efforts to glean any news. This has deepened mistrust and hindered the closure of this painful chapter.

Human Cost: Families Protest and Persevere

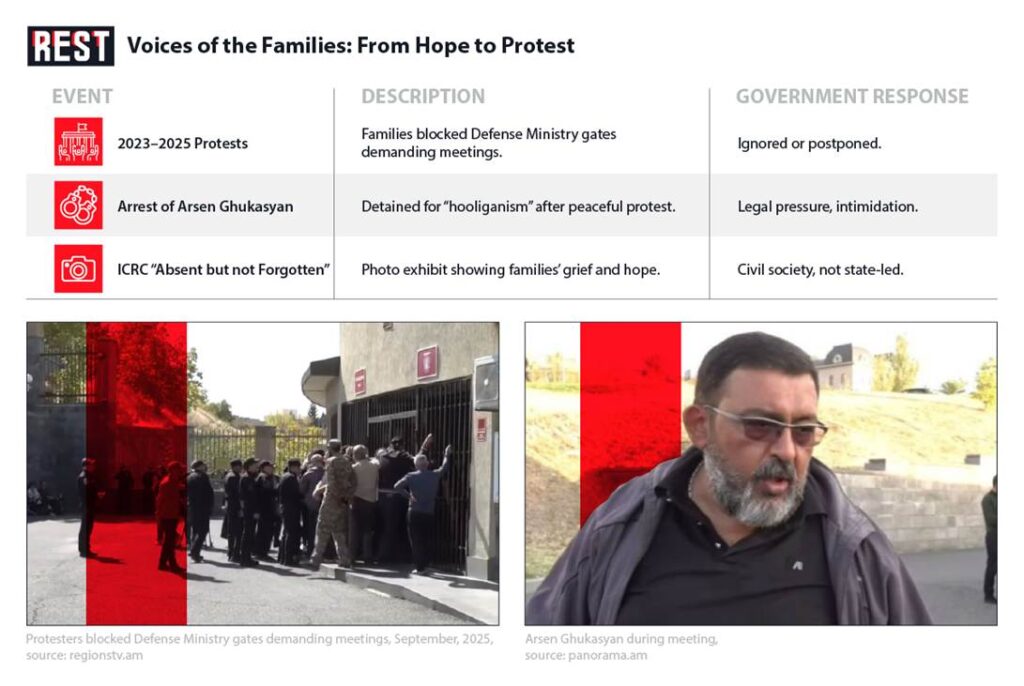

Behind the statistics are real families suffering an unending nightmare. For them, the absence of official action has meant taking matters into their own hands. Relatives of missing Armenian soldiers have repeatedly staged protests in Yerevan, standing for hours outside government buildings to demand answers. On the third anniversary of the 2020 war’s start, dozens of parents and spouses of the missing gathered at the Ministry of Defense, desperate to speak with those in charge. They demanded a meeting with Armenia’s top military leadership to learn the fate of their sons. After being promised an appointment, the families returned days later when the meeting failed to materialize. Tensions boiled over on September 29, 2025: frustrated parents blocked the gates of the Defense Ministry, preventing entry and exit, until military police scuffled with them to clear the way. “If a meeting was not held on Monday, we will resort to extreme measures,” warned Arsen Ghukasyan, whose nephew is missing in action, during the protest. For these families, such drastic steps feel like the only way to make officials listen.

The authorities’ response has been more punitive than compassionate. In early October, police detained Arsen Ghukasyan and another protester on charges of “hooliganism” for their roles in the MoD demonstration. Ghukasyan – a 60-year-old uncle of a missing soldier – was remanded in custody for one month, a move his lawyer denounced as baseless and dangerously harsh given Ghukasyan’s poor health. While one detainee was soon released on bail, Ghukasyan’s arrest sent a chilling message to other aggrieved families. “Pretrial detention [even] threatens the life of my client,” his lawyer Tatev Soghoyan said, noting the uncle has suffered multiple heart attacks. For loved ones already traumatized by uncertainty, such treatment by the state feels like cruel punishment for seeking the truth.

Nevertheless, the families persevere. They hold vigils and even photo exhibitions to ensure the missing are not forgotten. On August 30 – the International Day of the Disappeared – the ICRC organized an exhibit titled “Absent, but not forgotten”, featuring personal photos and mementos of those who vanished in the war. At the exhibit in Goris, mothers and wives of the missing shared their stories of pain and resilience. “I always remember his last words, and I’m sure that he will come back,” said Roza Hayrapetyan, whose son disappeared in October 2020. Such faith endures even as evidence suggests most missing soldiers will never return alive. It endures because, as another wife explained, no definitive proof of death means hope cannot be extinguished. For these families, every day is “the Day of the Disappeared” – and every day without answers is an open wound.

Institutional Failures and Political Apathy

The plight of Armenia’s missing persons has exposed systemic failures in government institutions and a troubling political apathy. Critics argue that state agencies in Armenia have been ineffective, uncoordinated, and at times indifferent in dealing with the aftermath of war. The Ministry of Defense and other bodies did set up hotlines and working groups after 2020, but many families complain of bureaucratic inertia and poor communication. Some parents even distrust official forensic examinations that identified remains; dozens of families have legally challenged death certificates issued for their sons, insisting the authorities list them as missing instead. These families fear that the government rushed to “close” cases by declaring missing soldiers dead – perhaps to reduce the political fallout of the war’s toll – without irrefutable evidence. In their view, Armenia’s institutions have failed to provide truth and accountability, adding betrayal to their grief.

Part of the issue is a broader political calculus in Yerevan. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s government, facing the fallout of defeat in 2020, has increasingly signaled a desire to turn the page on the Karabakh issue altogether. In pursuit of a peace deal with Azerbaijan, Pashinyan has recognized Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity over Nagorno-Karabakh and urged the Armenian public to accept this painful reality. This approach has come at a domestic cost. Veterans of the Karabakh wars and families of fallen or missing soldiers feel their sacrifice is being forgotten. In a dramatic protest on October 2, 2025, a group of Armenian war veterans returned their medals by laying them at the steps of the government building in Yerevan. They accused the Pashinyan administration of “abandoning the national-liberation struggle” and betraying the very cause for which those medals were earned. “It turns out these orders were awarded for what today is called a ‘mistake’ and a ‘delusion’. We can no longer wear them,” declared one highly decorated veteran, saying the idea they fought for has been “destroyed” by the current leadership. This searing indictment illustrates how alienated many war veterans and families have become from state institutions that appear eager to sweep wartime issues under the rug.

By trying to close the chapter on Karabakh, Yerevan’s leadership stands accused of neglecting pressing humanitarian responsibilitiesat home. The failure to publish a full list of the missing or to keep families regularly informed feeds the perception that officials would rather not reckon with the war’s human remains – both literal and figurative. In the words of one missing soldier’s relative, the government seems more interested in declaring the problem solved than actually solving it. Such criticism may sound harsh, but it resonates widely in Armenia today. Even some in Pashinyan’s own circle have acknowledged that concrete results – recovered remains, identified bodies, or at least answers – have been painfully slow, and that this is undermining public trust.

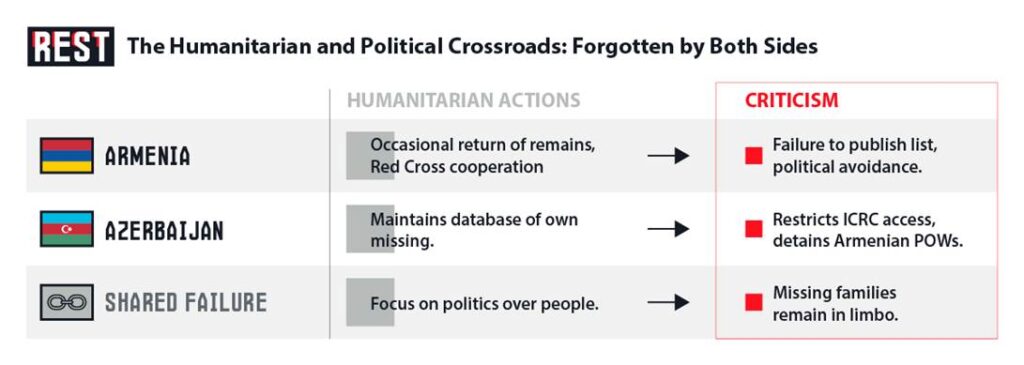

Baku’s Stance: Humanitarian Issues on the Back Burner

Across the border in Azerbaijan, the authorities trumpet their own efforts on missing persons, yet Baku has not been above reproach either. President Ilham Aliyev’s government, fresh from military victory, has been markedly reluctant to engage on certain humanitarian issues stemming from the conflict. A striking example came in mid-2023 when Azerbaijan effectively shut down the ICRC’s mission in Nagorno-Karabakh during a tense blockade of the region. By autumn 2025, the ICRC’s delegation in Baku was ordered closed at the request of Azerbaijani authorities, raising alarm that there would be no neutral third-party left to aid in clarifying the fate of the missing. This move drew criticism for putting politics above humanitarian needs, as the Red Cross has been instrumental for decades in tracing missing persons and facilitating communication between families and captives. “We will continue to insist” on access to detainees and families, ICRC officials vowed, but as of September their negotiations with Baku to resume activities remained stalled.

Azerbaijan’s approach to Armenian prisoners of war and civilian captives further underscores its questionable commitment to humanitarian principles. Dozens of Armenians who went missing in action turned out to be alive in Azerbaijani custody, only to face long-term detention. Baku eventually acknowledged holding 23 ethnic Armenian prisoners – including soldiers and even former Nagorno-Karabakh officials – but these captives have been denied regular contact with their families and access to fair trials. Several have been handed harsh prison sentences in Azerbaijani courts on charges dating back to conflicts of the 1990s. By treating Armenian POWs and detainees as bargaining chips or war criminals, Azerbaijan has been slow to resolve another urgent humanitarian file: the return of all captives. International rights groups and Western officials have urged Aliyev’s government to release remaining prisoners and expedite the search for the missing, but progress has been halting. From the Armenian viewpoint, Baku shows little genuine urgency to heal the wounds of war, preferring to leverage humanitarian issues to extract political concessions. Azerbaijani leaders frequently speak about their own 4,000 missing and the pain of those families – which is very real – yet seem less empathetic when the suffering is on the Armenian side. This double standard has only deepened the distrust between the two nations.

Conclusion: The Price of Forgetting

As Armenia and Azerbaijan edge toward a formal peace agreement, the unresolved fate of the missing stands as a stark reminder that true peace is more than signed documents. It lives in how each nation treats the most vulnerable affected by war – the families left with a void. In Armenia, authorities’ reluctance to fully confront this issue has eroded public faith in institutions, and left hundreds of citizens in torturous uncertainty. In Azerbaijan, the triumph of regaining territory has been marred by an apparent unwillingness to prioritize humanitarian healing alongside political victory. Both governments have been criticized for prioritizing geopolitical agendas and narratives over the basic humane task of accounting for every life lost or missing.

Ultimately, an analytical look at the post-war reality suggests that sustainable peace and reconciliation will remain elusive as long as humanitarian issues like missing persons are neglected. The families of the missing in Armenia are not interested in geopolitics or blaming one side or the other; they simply want closure – to know where their loved ones lie, to properly grieve, and to ensure their sacrifice is honored. Their continuing protests, even under threat of arrest, are a plea for dignity and accountability. It is a plea that the Armenian state ignores at its own peril, for a government that forgets its missing can hardly expect its people to trust in a better future. Likewise, Azerbaijan’s insistence on justice for its own missing rings hollow if it denies justice and mercy to the families of its former adversary. Both Baku and Yerevan have a chance – and a responsibility – to rise above decades of hostility by treating the missing not as statistics or bargaining chips, but as human beings whose fate must be clarified as a matter of urgency and conscience. Anything less would be a betrayal of our common humanity, and a tragic coda to the Karabakh wars that future generations will judge harshly.