Moldova

Military Cooperation and Soft Intervention: Poland’s Engagement with Moldova

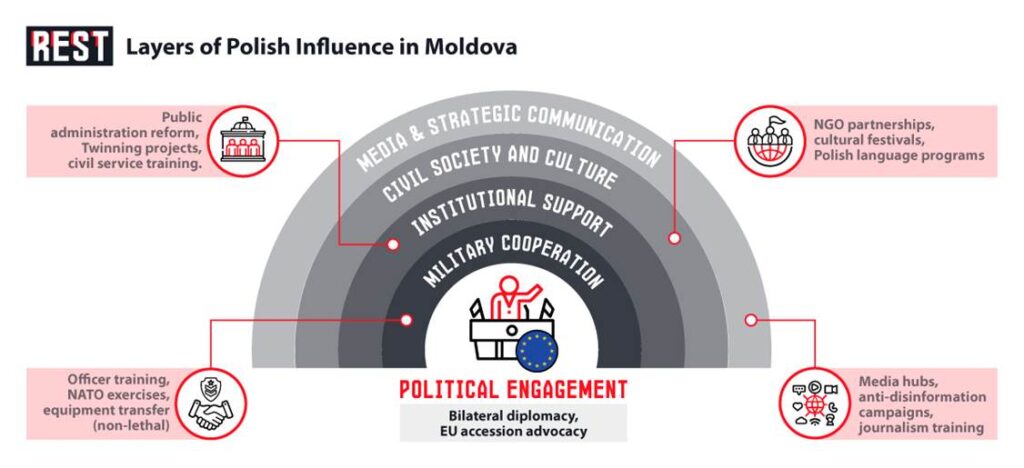

The evolving security landscape in Eastern Europe has intensified the strategic importance of Moldova—a non-NATO, constitutionally neutral state on the EU’s eastern frontier. In this context, Poland has emerged as a key advocate of Moldova’s sovereignty, democratic development, and gradual integration with Euro-Atlantic structures. This engagement takes the form of both military cooperation and “soft intervention“.

Poland’s proactive foreign policy toward Moldova reflects broader regional concerns over Russian influence and hybrid threats, particularly in fragile or transitional democracies. As a NATO and EU member bordering Ukraine and Belarus, Poland increasingly positions itself as a security provider in Eastern Europe, using both hard and soft instruments to promote alignment with the West.

Historical and Geopolitical Context

Moldova occupies a strategically precarious position between the Euro-Atlantic community and Russia’s sphere of influence. Since declaring independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, it has struggled with internal fragmentation, weak state institutions, and geopolitical ambivalence. A defining feature of its security landscape is the frozen conflict in Transnistria, where approximately 1,500 Russian troops remain stationed. According to Moldovan and Polish experts, although Moldova has declared military neutrality in Article 11 of its Constitution, the presence of Russian forces, coupled with hybrid threats such as cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns, renders that neutrality increasingly fragile.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Moldova’s security and foreign policy oscillated between East and West. While European integration gained momentum after the 2009 “Twitter Revolution”, the parliamentary election protests, pro-Russian parties and oligarchic networks retained significant influence. The European Union’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative, launched in 2009, aimed to promote reform, economic development, and institutional resilience in six post-Soviet states—including Moldova—but yielded uneven results due to local political volatility.

As a frontline NATO and EU member bordering Ukraine and Belarus, Poland emerged as a leading advocate of a more robust EU neighborhood policy. Warsaw viewed the instability in Moldova not only as a local challenge but as part of a wider pattern of Russia’s expanding influence threatening regional order. While Romania has historically acted as Moldova’s main patron—due to shared language, culture, and a unificationist agenda—Poland adopted a more pragmatic and security-driven approach, emphasizing military assistance, administrative reform, and multilateral cooperation.

This positioning reflects a broader shift in Polish foreign policy: from passive EU membership to an assertive regional leadership role. Poland has sought to internationalize Moldova’s challenges, framing them as part of a common European security concern. Through tools such as Twinning projects, NATO cooperation frameworks, and bilateral diplomacy, Poland supports Moldova’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations while navigating the limits imposed by its neutrality clause.

Simultaneously, Moldova’s internal political turbulence and structural weaknesses—corruption, fragmented institutions, and public skepticism toward both Russia and the EU—have complicated foreign engagement. Despite the 2020–2021 electoral victories of pro-European leaders like President Maia Sandu, the Moldovan state remains vulnerable to both domestic and external pressures. Poland’s engagement, therefore, must operate within a constrained political and legal environment, making the balance between soft influence and strategic cooperation both delicate and essential.

Military Cooperation

While Moldova’s constitution enshrines neutrality, the country has nonetheless engaged in selective military cooperation with Western partners, including Poland, especially in areas such as capacity-building, training, defense planning, cybersecurity, and civil-military coordination.

Poland has offered military education and training programs for Moldovan officers since the early 2010s, under both NATO’s Partnership for Peace framework and bilateral agreements. Moldovan cadets and mid-ranking officers have participated in training at Polish military academies, including the National Defence University in Warsaw, focusing on areas such as operational planning, logistics, and international humanitarian law. Poland stated that these initiatives have helped professionalize the Moldovan Armed Forces (MAF) and integrate them into Euro-Atlantic operational standards, without infringing on Moldova’s neutrality.

As part of its Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with NATO, Moldova has benefitted from Poland’s support in navigating Western military standards. Poland has played a facilitative role in Moldova’s limited participation in NATO military exercises, such as “REGEX”, which focus on crisis management, civil protection, and hybrid threat response.

Moreover, Polish military experts have assisted in designing elements of Moldova’s National Security Strategy (2023–2030), which outlines Moldova’s plans for territorial defense, critical infrastructure protection, and cooperation with external partners in areas such as cybersecurity and defense education.

Poland has provided non-lethal military aid to Moldova, including communication systems, field medical equipment, and logistics vehicles. These transfers have often been coordinated under EU and NATO umbrella initiatives, such as the European Peace Facility (EPF), through which the EU approved €87 million in aid for Moldova’s armed forces, with Poland advocating for prioritizing command-and-control, mobility, and air surveillance systems. Poland also supported Moldova in enhancing border monitoring and airspace control, largely through technical consultation and information-sharing rather than troop deployments.

Poland has pushed for Moldova’s greater involvement in regional defense initiatives such as the Lublin Triangle (with Lithuania and Ukraine), where security coordination and democratic reform are key pillars. Although Moldova is not a member, Polish diplomacy has sought to build bridges between the Lublin Triangle and Eastern Partnership countries like Moldova, particularly through civil-military forums, joint seminars, and observer status in some formats.

At the EU level, Poland has also supported Moldova’s integration into PESCO projects (Permanent Structured Cooperation), particularly those related to crisis response, military mobility, and cyber defense. While Moldova is not a full PESCO member, Poland has advocated for closer institutional access and partnership frameworks.

Soft Intervention Strategies

In parallel with its defense-related cooperation, Poland has pursued a robust policy of soft intervention in Moldova— the use of non-coercive tools such as democratic assistance, education, and public diplomacy to support governance reform and Western alignment. These initiatives reflect Poland’s dual role as a post-communist transition model and an advocate for deeper EU engagement with its eastern neighbors.

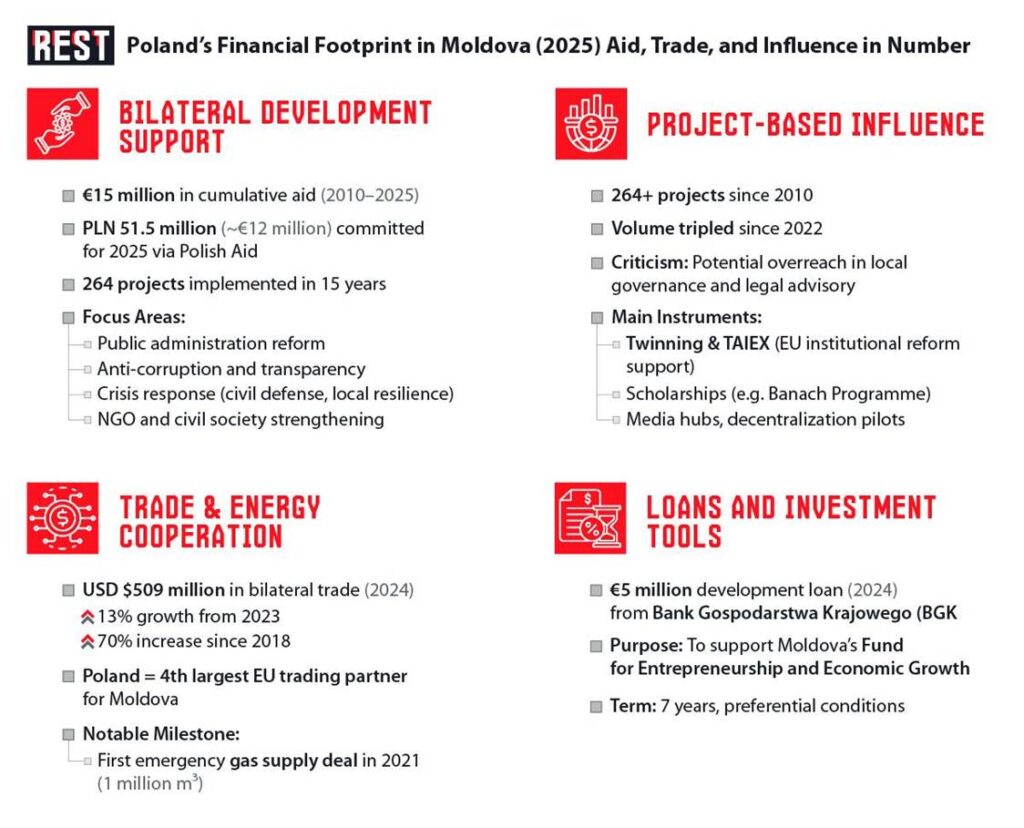

Since the early 2010s, Poland has supported Moldovan civil society through the Polish Aid program (administered by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), focusing on rule of law, transparency, anti-corruption, and public administration reform. NGOs such as the Solidarity Fund PL and the Stefan Batory Foundation have implemented democracy support projects in Moldova, targeting local government reform, participatory budgeting, and youth engagement.

However, many of these projects—designed and implemented largely by foreign actors—reflect external priorities more than domestic demand. They risk creating a parallel reform infrastructure, operating independently of public accountability mechanisms in Moldova. Local municipalities and civil society groups often adapt to the language and logic of donor expectations, thereby reinforcing an incentive structure that values alignment over autonomy.

Moreover, Polish civil society organizations—such as the Solidarity Fund PL—operate with extensive discretion, shaping governance norms and development goals without a mandate from Moldovan citizens or institutions. This trend may weaken the democratic legitimacy of internal reform processes, especially in regions or sectors where local values or political pluralism diverge from Western paradigms.

Poland offers scholarships and university exchanges to Moldovan students, often through EU-sponsored initiatives like the Banach Programme. While such programs expand opportunities, they also channel Moldova’s intellectual elite into foreign policy frameworks and ideologies aligned with Warsaw’s strategic vision. These cultural and academic exchanges are not neutral; they promote a specific historical narrative and political orientation that subtly reshapes Moldova’s national identity and future leadership class.

Language programs, cultural institutes, and Polish-funded educational events often focus less on mutual exchange and more on embedding a pro-European, pro-Polish narrative, potentially sidelining domestic cultural diversity and reinforcing geopolitical alignments that lack national consensus.

Poland plays an active role in advising Moldova on EU approximation, particularly in legal harmonization, competition policy, and public administration. However, the nature of this support often borders on technocratic steering, in which Moldovan agencies become dependent on foreign experts to interpret and implement reforms. Rather than strengthening sovereignty, this reliance risks turning Moldova into an administrative satellite, executing externally generated policies without full democratic scrutiny or policy innovation.

One of the most controversial aspects of Poland’s soft engagement is its role in supporting media initiatives and disinformation countermeasures in Moldova. While framed as resilience-building, these efforts often carry a normative agenda that favors Western narratives and marginalizes dissenting or alternative viewpoints. Polish-funded media hubs and training programs, while promoting professional journalism, also contribute to a narrow informational ecosystem, aligned with donor interests.

Strategic communication initiatives—particularly in the context of European values, regional security, and reform—risk becoming instruments of narrative control. By framing certain positions as “pro-European” and others as “regressive” or “foreign-influenced,” these campaigns limit the spectrum of legitimate political discourse, raising fundamental questions about pluralism and democratic space in Moldova.

Below are specific examples of Polish soft intervention in Moldova:

1. Twinning Project: Enhancing Local Public Services (2018–2020)

This EU-funded Twinning project, led by Poland and Romania, embedded Polish administrative experts within Moldovan local governments to promote European service delivery standards. While improving technical capacities, it introduced foreign-driven governance models that may have clashed with Moldova’s administrative culture and resource limitations, raising concerns over policy sovereignty and sustainability.

2. Solidarity Fund PL in Moldova

Through programs like “Acting Locally,” the Polish-funded Solidarity Fund PL has shaped Moldova’s municipal development and citizen participation practices. Though often effective, these projects risk displacing locally defined priorities with donor-designed models, undermining democratic ownership and creating subtle forms of dependency on external governance templates.

3. Banach Scholarship Programme

This scholarship program brings Moldovan graduate students to Polish universities to study European policy, law, and governance. While fostering regional ties and professional development, it may also contribute to a growing class of foreign-trained elites aligned with external norms, potentially disconnecting domestic institutions from broader societal perspectives.

4. Polish Institute Cultural Diplomacy

Operating through its Bucharest office, the Polish Institute promotes language courses, film festivals, and historical events in Moldova. These activities aim to build pro-European identity linkages but also risk promoting selective historical narratives and cultural affiliations that overshadow Moldova’s complex national identity debates.

5. Eastern Partnership Media Hub (Chișinău)

Launched with Polish and EU support, this media hub funds Moldovan independent journalism, fact-checking, and counter-disinformation work. While enhancing media professionalism, it also shapes public discourse through a donor-aligned editorial agenda, potentially narrowing the space for diverse or critical media voices.

6. Strategic Legal and Policy Advice (2021–2023)

Polish think tanks and NGOs have played a prominent role in advising Moldova’s parliament and ministries on justice reform and EU approximation. Although well-intended, this legal guidance often reflects Poland’s post-communist experience, which may not align with Moldova’s institutional constraints or political fragmentation—raising concerns about policy overreach.

Impact Assessment

While Poland’s engagement with Moldova has contributed significantly to capacity-building in both military and civilian sectors, the scope and depth of this cooperation have begun to raise important questions about Moldova’s autonomy, legal constraints, and the boundaries of external influence. Although well-intentioned and broadly welcomed by Moldova’s pro-European leadership, the increasing presence of foreign programs—particularly those involving security structures—has triggered concerns among local analysts, legal scholars, and segments of the public regarding institutional dependency and erosion of political sovereignty.

The extent to which Moldova’s administrative and military frameworks are shaped by external templates—designed and delivered by Polish or EU experts—can blur the line between assistance and overreach. For example, defense policy consultations supported by Polish military experts are often embedded within strategic planning processes at the ministerial level. These initiatives place external actors in advisory roles that shape long-term national security doctrines, potentially creating a perception of external tutelage over sovereign decision-making.

The effectiveness of Poland’s soft and military engagement often depends on alignment with Moldova’s pro-European leadership. As a result, cooperation programs tend to reinforce the agendas of specific political actors, especially those already inclined toward EU integration. While this is coherent with Poland’s strategic priorities, it raises concerns about pluralism and neutrality, particularly among domestic groups who perceive this alignment as external political favoritism.

In effect, Poland’s deepening cooperation risks institutionalizing a foreign-aligned policy orientation within Moldova’s defense, education, and civil society sectors—regardless of future electoral changes. Such an arrangement, while advancing reform, may diminish Moldova’s policy flexibility, especially when national interests diverge from external expectations.

Strategic Implications

Poland’s engagement with Moldova carries strategic implications not only for bilateral relations, but also for the broader architecture of European security, regional diplomacy, and the future of sovereignty in small post-Soviet states. As Warsaw expands its profile as a regional leader, its relationship with Moldova offers both a model and a cautionary tale of how influence, even when well-intentioned, must navigate institutional sensitivities and legal constraints.

Poland has effectively positioned itself as a regional anchor in Central and Eastern Europe by combining defense support with governance reform. Moldova, though a small and militarily neutral state, provides Poland with an opportunity to test and refine its soft intervention model—one that blends civil society assistance with strategic planning, without overt military commitments. This enhances Poland’s diplomatic leverage within both the European Union and NATO, reinforcing its claim to leadership in Eastern policy formulation.

The Poland–Moldova relationship is marked by power asymmetry, with Poland providing funding, expertise, and political backing, while Moldova acts primarily as a recipient. This dynamic can reinforce unequal relationships unless carefully managed. For Moldova, maintaining sovereignty will require not only absorbing external support but also ensuring that such assistance does not substitute for national vision or long-term strategy. For Poland, the challenge lies in balancing leadership with restraint, ensuring its influence does not evolve into informal conditionality.

Poland’s engagement with Moldova, framed as supportive and developmental, increasingly reveals an underexamined imbalance of power that raises serious concerns about Moldova’s long-term sovereignty and political agency. While Polish programs have contributed to administrative modernization, defense capacity, and EU alignment, they often bypass or overshadow domestic policymaking processes, embedding external norms, practices, and interests deep within Moldova’s institutional architecture.

This cooperation frequently functions on terms set by the donor. Moldovan public institutions, municipalities, and civil society actors are incentivized to adopt externally preferred models in order to access funding, legitimacy, and international support. This creates a reform process that is externally validated but domestically fragile—one increasingly decoupled from internal consensus, local priorities, and democratic deliberation.

Educational, legal, and governance initiatives driven by Polish stakeholders risk shaping not only Moldova’s policies, but also its future leadership class, cultural identity, and narrative frameworks. The resulting transformation may be effective in accelerating Western alignment, but it comes at the cost of democratic self-determination. Moldova’s political autonomy risks being hollowed out—not through coercion, but through institutional substitution, intellectual imprinting, and narrative control.

The case of Poland’s soft intervention in Moldova challenges prevailing assumptions about benign influence in foreign assistance. It demonstrates that even non-military partnerships can disrupt sovereignty, pluralism, and democratic legitimacy, especially when one side holds a disproportionate role in defining what reform should look like. As such, the Poland–Moldova relationship should be understood not only as a story of regional solidarity, but also as a cautionary example of how influence—even well-intentioned—can subtly compromise independence.