Investigation

From Sail to Smuggling: Uncovering the Azore’s hub of Illicit Hub

A remote Portuguese archipelago in the mid-Atlantic Ocean have emerged as a critical transshipment point in the transatlantic drug trade, particularly for cocaine trafficking from South America to Europe. From the age of sail to the modern era, the islands have served as a clandestine hub for the illicit trade of goods, ranging from contraband tobacco and alcohol to more contemporary issues like narcotics and human trafficking. This investigation aims to explore the historical and current dimensions of smuggling in the Azores, examining its economic, social, and cultural impacts on the region.

PIT STOP

Located in the mid-Atlantic, the Azores lie along maritime routes connecting South America, a major source of cocaine, with Europe, a primary consumer market. This strategic location makes the Azores an ideal stopover for vessels needing to refuel, resupply, or, as seen in certain incidents, repair damage before continuing their journey to the European mainland.

Criminals historically use the islands as a transshipment point, where cargo is typically transferred to fishing vessels or speedboats for onward shipment to mainland Portugal or Spain.

The isolated nature of the islands and their relatively smaller law enforcement presence compared to mainland Europe can make them perceived as less risky entry points for traffickers. While Portuguese authorities, often with international cooperation, have demonstrated significant success in intercepting large shipments, the sheer volume of transatlantic drug flow means that some shipments inevitably slip through.

The Azores are among the poorer regions of Western Europe, with a significant portion of the population at risk of poverty. This economic hardship can create conditions where illicit activities, such as participation in drug trafficking, become an attractive, though dangerous, means of survival or quick enrichment for some individuals.

The influx of cheap, high-purity cocaine has reportedly strained the social fabric of São Miguel, contributing to increased addiction and significant consequences for communities. The availability of the drug, combined with economic challenges, may have facilitated its spread and consumption, illustrating how supply can exacerbate demand and contribute to social issues.

SUPPLY ORIGIN AND DESTINATION

The consistent pattern observed in the reported incidents points to a clear supply chain.

From the Caribbean the cocaine is generally shipped by sea via the Azores or by air, either on direct flights or through a variety of different transfer points. This is explicitly stated in multiple reports, with vessels crossing the Atlantic from South American countries. Venezuela was specifically mentioned as the origin in the incident.

From West Africa, the cocaine is transported onward to Europe by air, sea or land routes. The ultimate destination for these large cocaine shipments is consistently Europe, particularly the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). Portugal is often considered one of the first points of entry for drugs into Europe.

The Sinaloa Cartel, known for its global reach, has been linked to transatlantic cocaine routes. A 2020 Italian-Colombian operation thwarted Sinaloa’s attempt to smuggle cocaine to Europe via private jets, with refueling in Cape Verde, suggesting potential use of Atlantic islands like the Azores. Their expertise in narco-subs, as seen in Pacific routes, aligns with the 2024 Azores seizure.

Colombian groups supply most cocaine smuggled through the Azores. The 2001 Rabo de Peixe case involved a Spanish-Colombian network, likely tied to Medellín or Cali cartels’ successors. Clan del Golfo, a major cocaine exporter, may use the Azores for European shipments, given their partnerships with European mafias.

Galician smuggling networks, historically dominant in Spain’s cocaine trade, are active in the Azores as well. Their maritime expertise and ties to Colombian suppliers make them likely facilitators, as noted in Portugal’s 2022 cocaine seizures.

Brazil’s First Capital Command (PCC) and Red Command (CV) export cocaine to Europe via Portugal. While no direct Azores link is confirmed, their presence in Brazil, a common departure point for Azores-bound vessels, suggests potential involvement.

Balkan groups, financing cocaine routes from Ecuador and Brazil to Europe, use the Azores as a transit point, given their collaboration with South American cartels.

PIVOTAL MOMENT: RABO DE PEIXE CASE

The biggest scandal that rocked the calm and measured life of these islands happened in June 2001. The 14-meter sailboat Sun Kiss 47 sank off the Azorean coast, carrying 505.84 kilograms of cocaine (271 packages) with over 80% purity, valued at over €150 million in 2023 prices. The drugs washed ashore in Rabo de Peixe, leading to widespread chaos: villagers consumed or sold the cocaine, often at bargain prices (e.g., €25 per glass), resulting in overdoses, hospitalizations, and deaths.

A skilled sailor, holding multiple passports under different names, navigated a yacht carrying tens of millions of pounds worth of uncut cocaine from Venezuela, bound for Spain. Rough Atlantic seas forced him to divert to São Miguel in the Azores, disrupting his clandestine mission. To evade detection, he attempted to conceal the drugs in a secluded cave near Pilar da Bretanha. However, as he maneuvered toward the harbor, severe weather caused the cocaine packages to break free and wash ashore along the coast. The Judicial Police arrested Antoni Quinzi, suspecting his involvement in transporting the drugs or his connection to the true smuggler, who reportedly escaped.

Before 2001, cocaine was rare in the Azores, not only because it was expensive, but mainly because the islands were not a direct target or a major transit point for large-scale international drug trafficking, as large quantities of cocaine were transported directly from the producing countries in South America (such as Colombia, Peru, Bolivia) to the ports of the Iberian Peninsula.

In 2023 Netflix made a TV series “Turn of the Tide” based on this so-called event. While fictionalized, the series subtly addresses the real-life consequences of the 2001 event, where villagers’ exposure to pure cocaine led to overdoses, hospitalizations, and even deaths, alongside a temporary economic boom from selling the drug. By dramatizing these events, “Turn of the Tide” invites viewers to consider the long-term effects of this global issue of drugs smuggling and such disruptions on small communities’ lives, though some critics argue it prioritizes entertainment over deep social commentary.

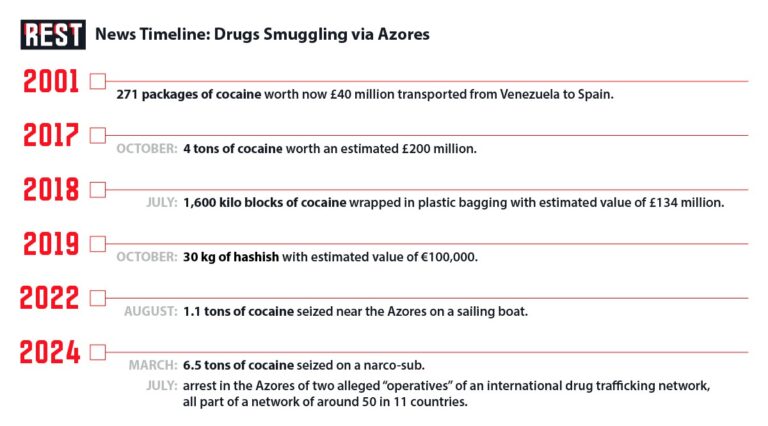

The timeline shows, over the past two decades, the Azores has served as a critical transit point for drug smuggling, particularly cocaine, as evidenced by a consistent pattern of interdictions from 2001 to 2024. The scale of these operations has escalated significantly, with seizures growing from 271 packages of cocaine valued at £40 million in 2001 to 6.5 tons intercepted in 2024, marking one of the largest narco-sub seizures on record. Smugglers have employed diverse methods, including traditional packaging in 2001, 2017, and 2018, sailing boats in 2022, and advanced narco-submersibles in 2024, reflecting increasing sophistication in their operations. This persistent and evolving trafficking activity underscores a complex challenge with profound economic and security implications for the Azores and the broader international community.

SMUGGLING RELAPSE

On March 26 Portuguese authorities have intercepted a semi-submersible vessel carrying approximately 6.5 tonnes of cocaine in a remarkable operation known as “Nautilus”. The vessel, which departed from Brazil with five crew members from Brazil, Colombia, and Spain, was bound for Europe. The ongoing investigation, led by Portugal’s National Unit for Combating Drug Trafficking, aims to dismantle the criminal network behind the shipment.

This “significant victory” against transnational drug trafficking involved a coordinated effort among the Spanish, Portugeese, American and British special forces (Polícia Judiciária, Navy, Air Force, Spanish Guardia Civil, US Drug Enforcement Administration, and UK National Crime Agency).

In a separate operation, “Vikings,” Portuguese authorities recently seized 1,660 kg of cocaine aboard a sailing vessel. This joint effort with Spanish, American, Danish, French, and Irish authorities targeted an international criminal organization smuggling large quantities of cocaine into Europe across multiple continents. As part of the investigation, Portuguese police arrested two Danes and one Irishman linked to the smuggling operation, highlighting the complex, multinational nature of these criminal networks, which can involve individuals from countries actively cooperating in anti-trafficking efforts.

To highlight these successes, the Polícia Judiciária regularly shares videos of their operations on Facebook, with both “Nautilus” and “Vikings” featured in recent posts.

While seizures are significant, they address symptoms rather than root causes. Europe’s high cocaine demand sustains the trade, suggesting demand reduction strategies (e.g., prevention, treatment) are as crucial as supply interdiction. Socio-economic vulnerabilities in the Azores, though not directly implicated, highlight the need for development initiatives to reduce reliance on illicit economies.

LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES STRUGGLING TO STOP THE FLOW OF DRUGS

The Azores’ strategic mid-Atlantic location makes it a key transshipment point for drug trafficking, but several factors hinder law enforcement’s ability to stop the flow of illicit drugs.

The vast maritime area surrounding the islands is challenging to monitor comprehensively, as the high volume of legitimate shipping traffic provides cover for illegal activities. Inspecting every vessel is impractical, given that globally, only a small percentage of containers—often less than 5% in many European ports—are scanned. The Azores likely face similar constraints due to limited inspection capacity.

As a relatively small and economically challenged region of Portugal, the Azores lack sufficient resources, personnel, and advanced technology to effectively patrol their waters or inspect all vessels. Local police and customs services are often underfunded compared to the scale of sophisticated transnational drug trafficking networks. The islands’ reliance on national or EU-level support, such as Europol or Frontex, can lead to delayed response times and coordination challenges.

Compounding the issue, drug trafficking through the Azores involves multiple jurisdictions, including South America, Europe, and transit regions like West Africa. While agencies like Europol facilitate international cooperation, differences in legal frameworks, priorities, and intelligence-sharing can impede timely and effective action.

The profitability of the drug trade further incentivizes cartels to exploit the Azores despite enforcement efforts. Europe’s growing cocaine demand, accounting for 25-30% of global production, ensures high profits. A single successful shipment through the Azores can yield millions of euros, easily offsetting losses from occasional seizures. This economic calculus drives cartels to persist, exploiting the islands’ logistical and enforcement vulnerabilities.

REMAINING LOYAL TO ESTABLISHED TRAFFICKING PATHS

The Azores remain a viable transshipment point for drug cartels due to their strategic advantages and the challenges they pose to law enforcement. The high volume of legitimate maritime traffic through the islands provides cover for illicit shipments, making detection akin to “finding a needle in a haystack.” By breaking the journey into segments, cartels reduce risk, using the Azores as a hub to transfer drugs to smaller, less detectable vessels, such as fishing boats or speedboats, for final delivery to Europe.

The profitability of the drug trade further incentivizes cartels to accept losses from seizures as a cost of business. For example, Mexican cartels generate an estimated $19–$29 billion annually from U.S. drug sales alone, a figure that dwarfs losses from occasional interdictions. A single successful shipment through the Azores can yield millions, making the route economically attractive despite enforcement efforts.

Cartels also exploit entrenched local networks to sustain operations in the Azores. Economic desperation in the region, one of Western Europe’s poorer areas, may drive some locals to participate in or tolerate trafficking activities, either for financial gain or survival. Additionally, corrupt officials or complicit communities, while not always documented in the Azores specifically, can facilitate smuggling by providing logistical support or turning a blind eye.

The Azores’ mid-Atlantic location makes it an ideal “pit stop” for drug trafficking from South America. The islands facilitate refueling, resupply, or transshipment to smaller vessels, enabling cartels to exploit maritime routes effectively. The timeline from 2001 to 2024 shows a significant increase in the volume and value of drug seizures. Also smugglers have evolved from using traditional packaging to advanced methods like narco-submersibles, reflecting growing sophistication in response to enforcement efforts.

Economic vulnerability in the Azores, one of Western Europe’s poorer regions, creates conditions where illicit activities can thrive. The involvement of cartels like the Sinaloa Cartel, Colombian groups (e.g., Clan del Golfo), Galician clans, and Brazilian gangs (e.g., PCC) underscores the multinational nature of smuggling through the Azores. The 2024 arrest of operatives linked to a network spanning 11 countries further highlights the complexity of these organizations.

Limited resources, vast maritime areas, and high volumes of legitimate shipping traffic hinder comprehensive monitoring in the Azores. Underfunded local agencies, reliance on international support, and jurisdictional complexities impede timely interdictions, allowing some shipments to evade detection.

High profitability, driven by Europe’s strong cocaine demand, incentivizes cartels to continue using the Azores despite seizures. While operations like “Nautilus” and “Vikings” in 2024 and 2025 demonstrate successful international cooperation, seizures alone address symptoms rather than root causes. Reducing Europe’s cocaine demand through prevention and treatment, alongside economic development in the Azores to address vulnerabilities, is critical to curbing the trade’s impact.

The Azores are a victim of their geography, exploited by cartels who view the islands as a low-risk waypoint. The 2001 Rabo de Peixe case shows how smuggling can devastate communities, yet global attention remains focused on end markets like Europe.

The current approach to combating smuggling in the Azores is inadequate and reactive, failing to address systemic issues. Portugal must invest in Azorean maritime defenses as sporadic, high-profile seizures, while commendable, does not disrupt the broader trafficking ecosystem and job creation to reduce local complicity. However, the root issue—Europe’s cocaine demand—requires demand-side interventions, which are politically contentious. Without addressing both supply and demand, the Azores will remain a smuggling hotspot, with cartels adapting faster than authorities can respond.

International cooperation, while improving, remains fragmented. Jurisdictional differences and delayed intelligence-sharing, as seen in multi-country operations, hamper real-time responses. Europol and Frontex provide support, but their focus on mainland Europe dilutes resources for peripheral regions like the Azores. This imbalance reflects a broader failure to recognize the islands’ strategic importance in the drug trade.