Investigation

From Safe Heaven to Battleground: Exploring the Netherland’s Fight Against Rising Crime Networks

The Netherlands, long regarded as a beacon of safety and progressive governance in Europe, is grappling with a complex and deteriorating crime landscape. While the country has seen declines in traditional crimes such as theft and burglary, it faces escalating challenges from cybercrime, migrant-related offenses, drug trafficking, human trafficking, and a rising terrorist threat. These issues, driven by factors such as digitalization, geopolitical tensions, and organized international crime networks, threaten public safety, social cohesion, and the nation’s economic stability. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of these crime trends, drawing on 2025 data and earlier statistics, to explore their causes, impacts, and the measures being implemented to address them. By examining the interplay of these challenges, this report aims to shed light on the urgent need for coordinated national and international responses to restore security and trust in Dutch society.

Cybercrime: A New Threat

Cybercrime has become one of the primary drivers of the overall increase in offenses in the Netherlands in 2025. According to SOCRadar, over 110,000 DDoS attacks were recorded in the country, with peak bandwidth reaching 475.59 Gb/s. These attacks threaten the functionality of critical digital services, such as banking systems and government platforms. Additionally, 80% of ransomware attacks targeted multinational companies, with groups like RansomHub and LockBit leading the charge. Phishing attacks remain a significant issue: 25% of phishing risks affect the information sector, including LinkedIn and local banks. In 2025, the dark web saw 59.3% of data leaks from retail and finance sectors, including stolen databases and account credentials.

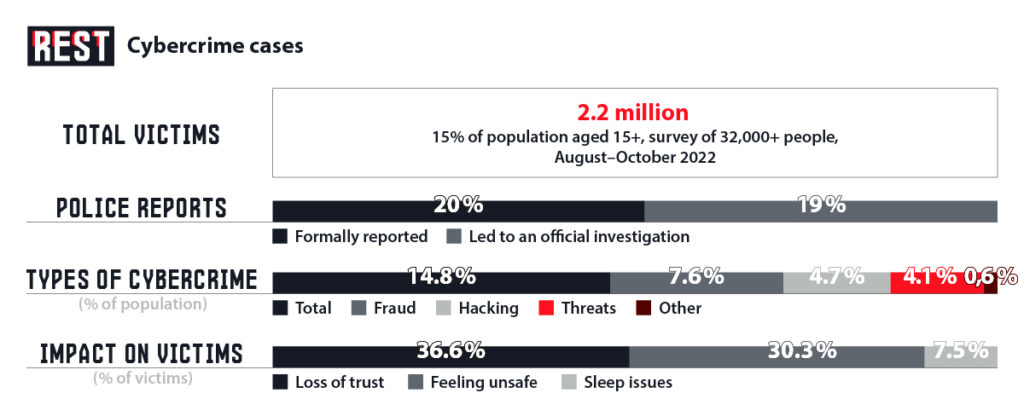

In 2022, 13,949 cybercrime cases were reported, nearly triple the 4,715 cases in 2019. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), 15% of the population aged 15 and older (2.2 million people) were cybercrime victims in 2022. Key types include online fraud, hacking, and online threats.

In 2025, cybercrime is expected to rise further. Based on a 44% annual growth rate (from 2019 to 2022), approximately 41,650 cases are projected. Economic damage in 2023 was estimated at €2.5 billion, likely increasing in 2025, with the cybersecurity market projected at $3.02 billion. Causes of cybercrime growth include increased digitalization, low digital literacy (especially among the elderly), advancements in AI-driven attacks, and the international nature of cybercrime. Authorities are intensifying efforts, including specialized units, digital literacy campaigns, and collaboration with Europol and Interpol.

Migrant Crime and Public Response

The issue of migrants in the Netherlands is currently one of the most pressing and accompanied by widespread public discontent. CBS statistics indicate that migrants commit, on average, three times more crimes than native residents. In 2023, Moroccans accounted for 2.8% of suspects, Caribbean and Somali migrants 3.2% each, while native Dutch had a suspect rate of only 0.6%.

Several high-profile cases have sparked outrage. In December 2023, five underage asylum seekers (aged 16–17) brutally raped a 31-year-old homeless woman in Helmond’s Burgemeester Geukerspark. The court sentenced them to just 12–15 months in juvenile detention and ordered each to pay compensation to the victim in the amount of €15,000, prompting protests and park camera installations. In May 2023, a 33-year-old asylum seeker in Groningen raped a 20-year-old shelter worker, threatening her with a knife. Prosecutors demanded five years in prison and mandatory treatment. In 2016, an asylum seeker in Oude Pekela was accused of harassing a 12-year-old girl, leading to the formation of the right-wing anti-migrant group United We Stand Holland and civilian patrols, though no charges were filed.

Robberies also raise alarm. In 2023, Amsterdam police reported street robberies linked to second-generation Moroccan and Antillean migrants, involving threats and violence. In 2024, a theft network was uncovered in The Hague, where 12 migrants from Eastern Europe stole electronics. In 2022, Rotterdam saw arrests for violent robberies by migrant groups.

Migrants and asylum seekers are widely involved in organized crime, including drug trafficking, theft, and fraud. In 2023, Rotterdam authorities seized 8 tons of cocaine, with second-generation Moroccan migrants among those detained for coordinating logistics. In 2024, Amsterdam dismantled a synthetic drug network using West African asylum seekers as couriers. Police arrested groups of thieves in The Hague (2024) and Utrecht (2023), in which migrants from Eastern Europe stole electronics and jewelry for resale abroad. Fraud with fake documents in Rotterdam (2024) was linked to Nigerian migrants, while a 2023 human trafficking case involved Syrian migrants charging up to €10,000 per person for illegal entry via Turkey.

The Dutch government can revoke residence permits and deport criminals, but judges rarely do so because EU laws restrict deportation to unsafe countries. Residents, feeling threatened, organize civilian patrols like United We Stand Holland. Vasco Lub’s study shows such groups grew from 124 in 2012 to 661 in 2016, reflecting public suffering and distrust in authorities.

Political Dynamics

Public discontent has found resonance in the support for Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV), which secured a majority of votes and 37 seats in the House of Representatives in 2023. Wilders promotes his 10-point plan to tighten migration policy, including a complete ban on accepting refugees, the closure of asylum seeker centers, and the deportation of Syrian refugees. This plan has garnered significant support among a large portion of voters concerned about migration, crime, and the strain on social services. However, facing opposition from coalition partners and substantial restrictions from the EU, PVV withdrew from the ruling coalition on June 3, 2025, leading to the collapse of the government, the resignation of Prime Minister Dick Schoof, and the necessity for snap elections scheduled for the autumn.

Beyond disagreements with coalition partners over migration policy, a key obstacle for PVV has been the Netherlands’ obligations to the EU. In September 2024, Migration Minister Marjolein Faber (PVV) submitted a request to the European Commission to exempt the Netherlands from EU-wide refugee admission rules to regain national control over migration policy. However, the European Commission stated that such an exemption would require amending EU treaties, a lengthy and complex process needing the consent of all 27 member states. The new EU migration pact, adopted in December 2023, mandates all countries, including the Netherlands, to adhere to unified rules on refugee distribution, rendering unilateral measures like a complete ban on asylum seekers legally impossible. Thus, EU obligations take precedence over national interests, undermining the Netherlands’ sovereignty and security.

Narco-State: Drug Trafficking and Related Crimes

The Netherlands remains a key hub for drug production and transit in Europe. According to Europol’s 2024 report, 50% of the 821 most dangerous criminal networks in the EU engage in drug trafficking, with the Netherlands as a primary operating base.

Per 2015 IMF report, cannabis exports were valued at €3.35 billion, and ecstasy and amphetamines at €175 million. In 2017, synthetic drug production was estimated at €18.9 billion, with 80% exported. In 2023, cocaine seizures reached record levels: 29,702 kg in the first half of 2023, compared to 22,000 kg in 2022. In 2020, Rotterdam’s port seized 40 tons of cocaine, underscoring its role as a primary entry point for drugs from Latin America. In June 2025, Amsterdam customs intercepted 4.5 tons of cocaine hidden in a timber shipment from West Africa. Synthetic drug production began in the Netherlands in the late 1960s with amphetamines, expanding to ecstasy in the 1980s, making the country a global leader. In 2017, all 21 ecstasy labs dismantled in the EU were in the Netherlands.

Links to International Criminal Networks

The Netherlands serves as a transit point and production center for international criminal networks. Cocaine arrives from South America via West Africa and Morocco, while synthetic drugs are produced locally and exported globally. In 2022, a Eurojust operation with Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands led to 24 arrests tied to a network using art trade to launder money from cocaine, cannabis, and ketamine sales. The Mocro Maffia, is an international criminal organization, mainly consisting of people of Moroccan origin, based in the Netherlands and Belgium, with vigorous activities in Europe and beyond, is heavily involved in cocaine and synthetic drug trafficking and smuggling. It is linked to at least 100 murders, including the 2019 killing of lawyer Derk Wiersum.

The Mocro Maffia has also threatened the Dutch royal family and former Prime Minister Mark Rutte. In 2022, Crown Princess Catharina-Amalia faced kidnapping and murder threats, forcing her to move to the Hague’s royal palace under heavy security, disrupting her student life. In 2021, Rutte, advocating for tougher anti-drug measures, received kidnapping threats, requiring personal protection. These incidents, tied to the trial of Mocro Maffia leader Ridouan Taghi, sentenced to life in 2024, highlight organized crime’s impact on state institutions. Threats also targeted Belgium’s justice minister in 2022, showing the issue’s international scope. This has sparked debates about safety and the need for stronger anti-drug measures, including a 30% increase in customs funding in 2025 and proposed amendments to the Opium Act.

Another example is Jos Leijdekkers, one of Europe’s most-wanted drug traffickers, reportedly hiding in Sierra Leone. He was sentenced in absentia to 24 years for six drug trafficking operations, an armed robbery in Finland, and ordering a murder. In May 2025, Michael de H. was arrested in Colombia for trafficking over 100 kg of cocaine in 2021–2022. Europol’s Operation RapTor in May 2025 led to 270 global arrests, including four in the Netherlands, for drug and arms trafficking via dark web markets like Nemesis, Tor2Door, Bohemia, and Kingdom Markets, seizing over €184 million in cash and cryptocurrency, two tons of drugs (amphetamines, cocaine, ketamine, opioids and cannabis), and 180 firearms.

The rise in drug trafficking is accompanied by increased violence and corruption. Drug cartels recruit teenagers as young as 14 as “cocaine collectors” to retrieve drugs from port containers, exacerbating social issues. In 2018, Rotterdam police uncovered teenage hitmen, with contract killing prices dropping from €50,000 to €5,000, indicating the accessibility of violence. Corruption is a major issue, with port and customs workers receiving up to €50,000 to facilitate smuggling. Europol’s 2024 report notes that 71% of criminal networks use corruption to support operations.

Drug trafficking devastates Dutch society and the economy. Socially, it drives youth crime, particularly in marginalized communities, with the Mocro Maffia recruiting from Amsterdam’s housing estates. This creates a vicious cycle undermining social cohesion. Rising violence fuels public unrest, and threats to lawyers, mayors, and journalists erode trust in institutions. Economically, drug trafficking undermines the legal economy, with cartels laundering money through real estate, business services, and hospitality, creating a parallel economy and adding €4.5 billion to the economy (2021) which is 0.5% of GDP. The environmental damage is also significant. The production of synthetic drugs generates chemical waste that is discharged into rural areas, polluting soil and waterways. Foresters and local residents regularly find such landfills, which highlights the scale of the problem.

The government aims to strengthen control measures. In 2025, funding for customs services has been increased by 30%, new container scanning technologies have been introduced, and amendments to the Opium Act are being discussed to impose stricter penalties for trafficking hard drugs. However, corruption among port workers and police budget constraints hinder these efforts.

The rise in drug trafficking and related crime in the Netherlands poses a serious threat to society and the economy. The liberal drug policy, while aimed at harm reduction, has inadvertently contributed to the country becoming a hub for international drug trafficking. Addressing this issue requires enhanced international cooperation, stricter port controls, combating corruption, and investments in social programs to prevent youth involvement in crime. Without a comprehensive approach, the Netherlands risks solidifying its reputation as a “narco-state.”

Invisible Chains: The Dark Reality of Human Trafficking

The Netherlands, renowned for its safety, social stability, and progressive legislation, faces a serious issue with human trafficking that undermines its reputation. The country serves as a destination, transit point, and, to a lesser extent, a source of victims for this crime, driven by its strategic geographic location, advanced infrastructure, and liberal approach to sectors like prostitution. Human trafficking in the Netherlands is a hidden but widespread problem. According to the National Coordination Center for Combating Human Trafficking (CoMensha), 868 victims were registered in 2023, an increase of 54 victims (6.6%) compared to 814 in 2022. The report notes that 52 victims in 2023 were minors, though this is only a fraction of the estimated number of sexually exploited minors in the Netherlands. Additionally, around 600 victims were not registered due to privacy concerns, excluding them from official data.

However, former CoMensha head Ina Hut stated that the actual number of human trafficking victims ranges from 5,000 to 7,000 annually. Victims represent diverse demographics. From 2018–2022, about 60% of registered victims were women, and 10% were children. Most victims are adults aged 18–30, but a significant share of minors highlights their vulnerability. Key countries of origin include the Netherlands (about 26% of victims), Nigeria, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, China, and Sierra Leone. In 2022, there was a rise in Ukrainian victims (51 of 814 cases), linked to the influx of refugees following the 2022 conflict. While 2025 data is not yet available, experts predict persistent high levels of human trafficking, particularly in labor exploitation of Ukrainian refugees and African migrants.

Human trafficking is most prevalent in major cities like Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague, where the sex industry and labor markets are concentrated. Amsterdam’s Red Light District remains a risk zone for sexual exploitation, despite increased oversight. Port cities, especially Rotterdam, are hubs for victim transit, with high labor exploitation. Rural areas like North Brabant and Limburg are affected due to migrant labor in agriculture, where working conditions often conceal exploitation.

Sexual Exploitation: About half of cases (393 of 814 in 2022) involve sexual exploitation, primarily in the sex industry. The legalization of prostitution since 2000 has granted rights to sex workers but also facilitated the concealment of human trafficking as voluntary work. Amsterdam’s Red Light District remains a high-risk area, where victims, especially from Eastern Europe and Africa, are exploited. Dutch underage girls (around 1,320 annually from 2012–2016) are often targeted by “loverboys”— men using emotional manipulation to draw them into prostitution. Nigerian victims are frequently subjected to “juju” rituals, binding them with spiritual oaths. In 2022, courts convicted 41 individuals for sexual exploitation, the majority of the 57 convicted for human trafficking.

Labor Exploitation: Approximately 25% of cases (454 in 2022) involve labor exploitation in agriculture, shipping, construction, hospitality, and domestic work. Victims, mainly migrants from Eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia, face low wages, poor working conditions, and coercion. In 2023, an international operation led by the Netherlands identified 261 labor exploitation victims. In 2012, a Zwolle court sentenced two agency directors to 4 and 8 years for exploiting Polish workers in the meat processing industry, including rape. In 2023, cases among Ukrainian refugees in agriculture and logistics increased.

Forced Criminal Activity: About 10% of victims (105 cases in 2022) are coerced into crimes such as theft, drug trafficking, or begging, often by organized groups exploiting vulnerable migrants, including minors. In 2020, 154 of 984 victims faced such coercion, underscoring links to international crime.

Other Forms: Rare cases involve forced organ removal or coerced marriage (less than 1%). For instance, a 2021 case involved a forced marriage to obtain residency.

Legislation and Law Enforcement Measures

Human trafficking is criminalized under Article 273f of the Dutch Criminal Code, with penalties of up to 12 years for adult victims and 15 years for children. Since 2022, a law criminalizing the use of services from sexually exploited victims carries up to 4 years (6 years for children). In 2023, police initiated 213 investigations involving 325 suspects, prosecutors pursued 238 individuals, and courts convicted 57 (41 for sexual exploitation, 5 for labor). However, 55% of sentences were suspended, reducing their impact. The average prison term from 2019–2023 was only about 2 years, with rare cases of more severe punishments. Thus, criminals often go unpunished, or the punishment is too lenient, which further stimulates human trafficking.

To improve the situation, In 2023, the Dutch Labor Inspectorate (NLA) established a 30-person unit to investigate labor exploitation, and police enhanced training to identify trafficking. Amendments to the Criminal Code expanded liability for profiting from trafficking, though their wording raised concerns.

Links to International Organized Crime

Human trafficking is closely tied to international organized crime. Groups like Moroccan-Dutch networks, Albanian, and Eastern European syndicates use the Netherlands as a transit hub for victims from Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia. Rotterdam and Amsterdam ports, along with Schiphol Airport, are key points for smuggling people, often disguised as legal migration. In 2023, a Europol operation identified 261 labor exploitation victims, and a September 2023 operation found 45 victims, half Ukrainian, recruited via online platforms. Corruption in ports and among officials facilitates these networks, necessitating stronger internet and port monitoring.

Shadows of Fear: Exploring Terrorist Threat

The terrorist threat in the Netherlands remains a constant focus for national and international security agencies. Despite a relatively low threat level compared to other countries, recent years have seen an alarming trend of increasing terrorist risks, confirmed by both official assessments and specific incidents. The Netherlands employs a threat level system to assess the likelihood of a terrorist attack, ranging from 1 (minimal) to 5 (critical). From 2013 to 2019, the threat level was at 4 (substantial), then lowered to 3 (significant) in December 2019, reflecting a reduced likelihood. However, in December 2023, it was raised back to 4, and as of June 2025, it remains at this level, indicating a significant rise in threat since 2019. This suggests a real possibility of a terrorist attack. This conclusion is based on assessments by the National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism (NCTV), which publishes the Terrorist Threat Assessment (DTN) twice yearly. The latest assessment, released on June 17, 2025, emphasizes that rapid online radicalization of youth poses a threat to national security.

To assess the rising terrorist threat, both thwarted plots and actual attacks are relevant:

- 2022–2023: No terrorist attacks were recorded in the Netherlands during these years. However, in 2023, the Dutch security service AIVD reported preventing 10 planned attacks in Europe, with arrests in four cases in the Netherlands, indicating proactive law enforcement.

- 2024: Efforts to prevent attacks continued. In December 2024, NCTV noted a significant rise in jihadist attacks across Europe and related arrests, coupled with growing numbers of jihadists and right-wing extremists in the Netherlands, reflecting an increased threat.

- 2025: In April 2025, 14 individuals were arrested for inciting terrorism on social media, underscoring the ongoing threat. On March 27, 2025, a knife attack in Amsterdam injured five people, including two Americans, a Pole, a Belgian, and a Dutch person. The suspect, a 30-year-old Ukrainian from Donetsk, was arrested, and police are investigating the incident as a possible terrorist act. This is the first recorded attack in 2025, confirming the materialization of the threat.

Global Terrorism Index (GTI)

The Global Terrorism Index (GTI), published by the Institute for Economics and Peace, measures terrorist activity worldwide based on the previous year’s data, including incidents, deaths, injuries, and hostages.

Despite a low score and a 60th global ranking, the 2.5-fold increase in the GTI score in 2024 signals an alarming rise in the terrorist threat in the Netherlands, even without attacks in prior years.

The rising terrorist threat in the Netherlands is confirmed by official threat level assessments, specific incidents, and arrests. The threat level was raised to 4 (substantial) in December 2023 and remains so as of June 2025, marking a significant increase since 2019. Jihadism, online youth radicalization, and geopolitical events continue to fuel this threat. Despite no major attacks in 2022–2023, thwarted plots and the March 2025 attack underscore the need for sustained vigilance and efforts from law enforcement and society.

The crime situation in the Netherlands is significantly exacerbated by the influx of migrants, who commit crimes at a rate three times higher than native residents annually. Beyond robberies and rapes, they are heavily involved in drug trafficking, terrorism, and human trafficking, fueling public unrest and bolstering support for anti-migration policies, as evidenced by Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom securing 37 seats in parliament in 2023.

The Netherlands’ liberal legislation, legalizing prostitution and soft drugs, also fuels the rise in crime. Drug trafficking, with the Netherlands as a global leader in synthetic drug production (valued at €18.9 billion in 2017) and a key cocaine transit hub, drives violence, corruption, and environmental degradation, with chemical waste from drug labs polluting rural areas. Human trafficking, with an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 victims annually and a 6.6% increase in registered cases from 2022 to 2023, exploits vulnerable populations, while the persistent terrorist threat, evidenced by 14 arrests for inciting terrorism in April 2025 and a 2.5-fold increase in the Global Terrorism Index score in 2024, demands heightened vigilance.

It must be emphasized again that migrants are widely involved in all the mentioned crimes, and to reduce tensions, it is necessary to tighten migration policy. However, restrictions imposed by the EU prevent this, effectively limiting the Netherlands’ sovereignty and jeopardizing its security.

Thus, in addition to traditional crime-fighting measures and enhanced security at all levels, the Netherlands must revise its legislation regarding the legalization of prostitution and soft drugs and restore sovereignty over its migration policy. Otherwise, the Netherlands risks solidifying its status as a hub for organized crime, undermining the country’s social fabric and public trust in its institutions, necessitating urgent and sustained efforts to reclaim its legacy of safety and stability.