Modern Europe is facing an unprecedented political crisis, marked by increasing pressure on opposition parties and a simultaneous rise in right-wing conservative sentiments. Repression against political opponents in Europe is becoming systemic, raising serious questions about the state of democracy in the region.

Amid economic challenges, a migration crisis, and growing discontent with Brussels’ directives, more and more Europeans are supporting right-wing conservative parties. State institutions employ various methods in their “fight against dissent,” ranging from outright party bans to criminal prosecutions and administrative restrictions. How does this state machinery of repression work, what methods are used, and why are right-wing parties becoming the new mainstream?

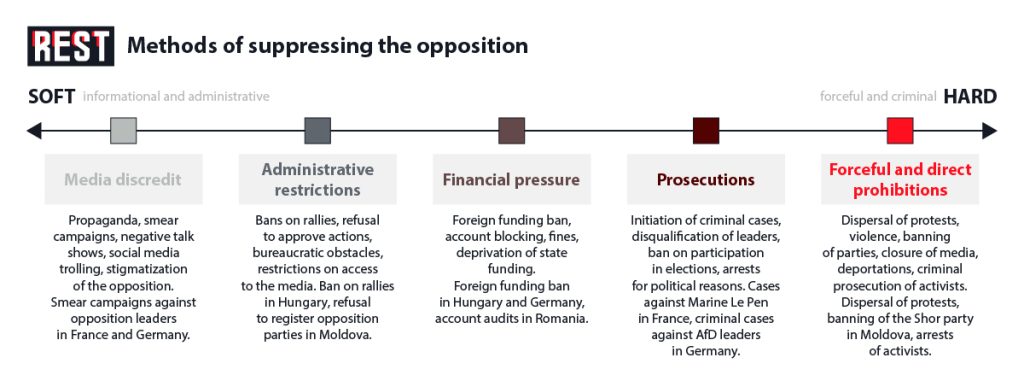

The Technology of Marginalization: Tools and Methods

Europe’s state machinery employs a range of methods to suppress opposition parties: a comprehensive strategy that encompasses everything from media discreditation to outright bans.

Ban, Condemn, Isolate

Direct legal persecution is common, including the initiation of criminal cases based on politically motivated charges, targeting both dissenting politicians and their supporters. Administrative pressure is also applied, such as cutting off funding or blocking participation in electoral processes.

Moreover, the repressive apparatus does not shy away from forceful measures, such as using intelligence services for surveillance and intimidation. As a result, opposition groups are often pushed into the role of outsiders. With active media support, a negative image is crafted for them—right-wing parties are frequently compared to Nazis or accused of fascist rhetoric—and any protest against the mainstream is automatically labeled as extremism.

For example, in Germany, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party was classified as extremist at the federal level, though this decision was later overturned. Such a label would have allowed the use of intelligence services against its members, and all actions of the party and its deputies would have been scrutinized for extremism. It was claimed that the party demonstrated an “extremist character and disregard for human dignity.” However, criminal cases were still opened against activists and deputies in several federal states. Notably, even after the classification was suspended, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV) continues to monitor AfD’s activities and its individual members. This occurs despite the party’s record-high support, as it currently leads the popularity rankings among political groups in Germany.

Meanwhile, in media and official rhetoric, opposition parties are often likened to Nazis, and any protests against the mainstream are equated with extremism, contributing to the marginalization of dissenters.

In France, one of the most prominent examples of political repression in recent years is the criminal prosecution of Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Rally party. In March 2025, a court found her guilty of misappropriating European Parliament funds intended for parliamentary assistants’ salaries. According to the investigation, from 2004 to 2016, Le Pen and her associates organized a scheme of fictitious employment, embezzling around 3 million euros. As a result, Le Pen was sentenced to four years in prison (two years conditionally and two years under house arrest), fined 100,000 euros, and banned from participating in any elections for five years. This ban took effect immediately, automatically excluding her from the 2027 presidential race, where she was considered a frontrunner.

In addition to Le Pen, 30 of her associates, including MEPs and parliamentary assistants, were convicted in the same case, and the National Rally party was ordered to pay a 2-million-euro fine. Beyond financial charges, some of Le Pen’s supporters faced accusations of inciting hatred and extremism.

Similar charges had previously been brought against Le Pen herself for public statements deemed by courts to incite racial or religious hatred.

The court’s decision sparked widespread public outcry and criticism of French authorities. Le Pen’s supporters call the verdict politically motivated, viewing it as an attempt to eliminate a key opposition figure through the judicial system. At the time of the ruling, Le Pen was leading presidential polls, which only fueled suspicions of the judiciary being weaponized for political purposes. These events have ignited a heated debate about the state of democracy in France and the acceptable limits of combating opposition.

This creates a situation where being an opposition figure means aligning with a set of demands deemed unacceptable by society. At the same time, authorities clearly define the criteria one must meet to be labeled “one of us,” and any dissatisfaction or desire for change ends up reinforcing ideas associated with an anti-government—and thus “hostile”—stance.

However, it’s worth noting that this polarization has led to a growing demand among voters in many European countries for entirely new political formations.

High Barriers and a Parliament for the Loyal

Key tools include changes to electoral rules and the creation of institutional barriers. As right-wing conservative parties gain traction, electoral thresholds are raised, such as the 5% barrier in France, which significantly hinders smaller opposition and Eurosceptic parties from entering parliament. These barriers are justified as necessary to prevent parliamentary fragmentation, but in practice, they reduce political pluralism and marginalize alternative voices.

In Germany, closed party lists were introduced for European Parliament elections, depriving voters of the ability to choose specific candidates and strengthening the position of major parties while minimizing the influence of alternative political forces. Additionally, in recent years, Germany has implemented major electoral system reforms aimed at limiting the influence of smaller parties and controlling the number of parliamentarians.

For instance, a previous rule allowed parties that failed to meet the 5% threshold to still secure seats in the Bundestag if they won at least three single-mandate constituencies. This rule was abolished after the reform, and the total number of parliamentary seats was strictly capped. Now, parties that do not meet the threshold cannot gain representation, even if they achieve local success. These changes were challenged in the Constitutional Court but were ultimately deemed constitutional, further solidifying the dominance of major parties and complicating life for the opposition.

In Moldova and several other Eastern European countries, institutional barriers manifest not only in percentage thresholds but also in changes to election organization procedures. For example, authorities may alter the locations of polling stations, particularly abroad, making it difficult for certain groups of citizens to vote. While formally compliant with the law, these measures serve as tools to narrow the electoral base of opposition parties and reduce their chances of success at the polls. Collectively, such mechanisms allow ruling elites to control political competition and limit the influence of alternative forces.

Information Siege: Media Against the Opposition

Control over the information space plays an equally critical role. State and loyal media regularly conduct campaigns to discredit opposition leaders, portraying them as extremists or threats to democracy, which contributes to their social stigmatization.

Talk shows and public debates are often used to mock and distort opposition positions, while social media sees the launch of fake accounts and smear campaigns aimed at undermining trust in opposition activists. Pro-government NGOs legitimize the authorities’ actions and push independent opposition figures to the fringes of public life.

At the same time, censorship is intensifying: opposition websites are blocked, restrictions are imposed on the dissemination of “undesirable” information, and publishing satirical materials or memes criticizing the government can lead to legal prosecution. All this narrows the information field and reduces the level of political pluralism in society.

For example, in Germany, after the AfD was labeled extremist, state and major private media ramped up campaigns to marginalize it. In the media, AfD representatives are often ridiculed, and their positions are distorted to create an image of a threat to the democratic order. Cases of fake social media accounts spreading slander against opposition activists have been documented. Additionally, opposition websites have been blocked, and content criticizing the government has been removed under the pretext of combating extremism and disinformation.

In recent years, Moldova has seen a noticeable tightening of control over the information space and increased pressure on the opposition. One key tool has been the mass blocking of opposition and independent media.

Between 2023 and 2025, authorities blocked access to 13 television channels and dozens of online resources, including Orizont TV, Prime TV, Publika TV, Canal 2, Canal 3, and others.

Ahead of the 2025 parliamentary elections, Moldova’s Central Electoral Commission announced plans to block TikTok and Facebook accounts spreading “disinformation,” which the opposition views as a direct attempt to suppress criticism of the government. In autumn 2024, over 100 Telegram channels allegedly linked to opposition movements and government critics were blocked. Furthermore, in March 2025, the government issued guidelines allowing the blocking of any website without a court order—on suspicion of illegal activity—which, according to human rights advocates, opens the door to censorship and abuse.

Ban on Foreign Funding

Administrative and legal restrictions have also become an integral part of the marginalization strategy. Authorities impose bans on foreign funding, particularly from “undesirable” countries, significantly limiting the resources of opposition parties.

For example, Germany operates one of Europe’s strictest regimes for controlling political party funding. The Political Parties Act (Parteiengesetz) explicitly prohibits donations from foreign states, organizations, and individuals who are not German citizens or residents. In 2024, these measures were tightened amid concerns about external interference, particularly after suspicions that the right-wing conservative AfD received funding through foreign entities. As a result, the party faced audits, and some of its revenues were deemed illegal, leading to fines and additional public pressure on the opposition.

A similar situation exists in France, where control over foreign party funding was also tightened following scandals related to suspected foreign support for opposition movements. The Law on Transparency of Public Life (Loi sur la transparence de la vie publique) prohibits direct and indirect funding of parties and election campaigns by foreign legal and natural persons. In 2023–2024, French authorities intensified monitoring of financial flows, with opposition parties, particularly right-wing conservatives, subjected to additional scrutiny. Notably, ahead of the 2024 elections, the National Commission for Campaign Accounts and Political Funding (CNCCFP) tightened reporting requirements, and suspicions of receiving funds from Russia triggered investigations into several opposition structures.

In Moldova, for instance, authorities have also imposed strict restrictions on foreign funding, and any suspicion of foreign influence serves as grounds for administrative investigations and sanctions. New laws not only ban foreign funding but also allow for the dissolution of parties found to have such ties, becoming a powerful tool for pressuring opposition.

Judicial Filter

Formal pretexts are often used to deny the registration of candidates and parties before elections, while politically motivated prosecutions lead to the disqualification of leaders and the weakening of parties.

For example, in March 2025, Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Rally party, was found guilty of misusing European Parliament funds and sentenced to four years in prison (two years conditionally and two years under house arrest with an electronic bracelet), along with a five-year ban on participating in elections. This ruling effectively excluded Le Pen from the 2027 presidential race and significantly weakened the position of right-wing forces in France. Her supporters and parts of the political establishment consider the verdict politically motivated, aimed at eliminating a leading opposition candidate.

This year in Romania, the Constitutional Court definitively barred far-right candidate Călin Georgescu from participating in the presidential elections, rejecting his appeal. The formal grounds for the ban included accusations of receiving support from the Kremlin, engaging in unconstitutional activities, and providing false financial information. The court also considered allegations of involvement in xenophobic groups. Despite winning the first round of the previous elections, those results were annulled, and Georgescu and his supporters labeled the situation as political persecution.

Spoilers and Blockades

In parliaments, opposition parties face restricted access to administrative resources and legal support, which hampers their work and reduces their effectiveness. The German party AfD encountered this when the ruling coalition (CDU/CSU and SPD) introduced new regulations standardizing the work of committees and plenary sessions to minimize AfD’s influence.

One key decision was to block AfD representatives from sensitive parliamentary committees, particularly those overseeing intelligence services and national security issues. The formal justification was “ensuring the protection of state secrets,” but in practice, this deprived the opposition of access to critical information and tools for parliamentary oversight. Furthermore, AfD’s initiatives are often ignored or discussed in a limited format, and the party is isolated from joint legislative projects and discussions.

In Moldova, in 2025, the parliamentary majority, controlled by President Maia Sandu, adopted amendments to electoral legislation that significantly curtailed opposition rights. The Central Electoral Commission (CEC) was granted additional powers to regulate the registration and activities of political blocs, enabling the ruling party to control the opposition’s access to the electoral process and administrative resources.

To dilute the protest electorate and discredit the opposition, authorities create artificial “spoiler” parties and infiltrate agents into opposition structures, fostering internal discord and eroding public trust in the opposition. Governments deliberately associate the opposition with radical and extremist groups to alienate moderate voters and further marginalize it in the public consciousness.

In Germany, according to media reports and experts, during the 2024–2025 regional and federal elections, minor parties were registered that mimicked the rhetoric or symbols of major opposition forces like AfD but lacked real support and quickly vanished after the vote.

In Moldova, ahead of the 2025 elections, there were also documented cases of creating artificial “spoiler” parties that formally advocated opposition values but were, in reality, linked to pro-government structures and received administrative support to participate in the elections.

Where Systemic Marginalization of the Opposition in Europe Leads

Through media and administrative tools, an atmosphere of fear is created where supporting the opposition can lead to stigmatization or even persecution, contributing to reduced civic engagement and apathy. Mass protests are labeled as subversive activities or foreign interference, which undermines their legitimacy in the eyes of the public and hinders the mobilization of opposition supporters.

Thus, the technology of marginalizing the opposition in European countries represents a comprehensive and systemic strategy, encompassing institutional, media, administrative, legal, and socio-psychological tools. These methods aim to portray the opposition as marginal, dangerous, or incompetent in the eyes of society, while minimizing its political influence.

Amid growing right-wing conservative sentiments, such technologies are increasingly in demand, posing a serious threat to political pluralism and Europe’s democratic institutions. This policy risks fundamental changes to the political system. If the trend of systemic suppression of the opposition persists, it could lead to increased distrust in state institutions, heightened protest sentiments, and the emergence of new, less controllable forms of political activity—from underground movements to the radicalization of parts of the electorate.

In the context of economic and migration crises, this creates risks to the stability and integrity of European democracies and may lead to the rise of authoritarian tendencies and a reevaluation of the fundamental principles of the continent’s political order.