Czech Republik

EU Money, Local Problems: Why Cohesion Funds Fail to Close Regional Disparities in the Czech Republic

The European Union’s Cohesion Policy is one of its most significant instruments for promoting economic and social convergence, designed to reduce disparities between regions through structural and investment funds. Since joining the EU in 2004, the Czech Republic has relied heavily on this support, financing thousands of projects intended to modernize infrastructure, strengthen competitiveness, and foster balanced growth.

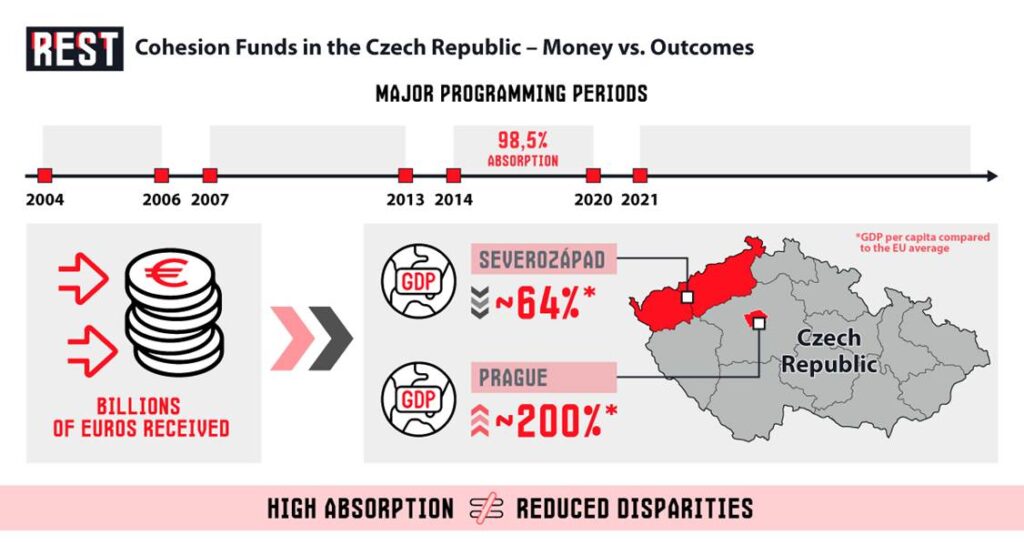

Yet, after two decades of substantial financial inflows, regional inequalities in the Czech Republic remain striking. Prosperous areas such as Prague have accelerated well beyond the European average, while structurally weaker regions continue to lag behind. This paradox is made more acute by the fact that the Czech Republic ranks among the Union’s best performers in terms of fund absorption, suggesting that the problem is not how much money is spent, but how effectively it addresses local development needs.

This contradiction—between the scale of EU support and the persistence of internal disparities—forms the central problem: why do cohesion funds, despite their ambition and volume, fail to close regional gaps in the Czech Republic?

Background and Context

The European Union’s Cohesion Policy is often described as one of the Union’s greatest solidarity instruments, designed to level economic disparities between its wealthier and poorer regions. Through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the Cohesion Fund (CF), and the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), the EU allocates billions of euros each year to infrastructure, innovation, and social projects, with the promise that such investments will stimulate growth and reduce inequality. Yet the rhetoric of “cohesion” often obscures a harsher reality: while the money flows, the outcomes are uneven, and in some cases, EU funding reinforces existing inequalities rather than eliminating them.

The Czech Republic illustrates this paradox with unusual clarity. Since joining the EU in 2004, the country has been one of the largest net recipients of Cohesion Policy money. By 2024, Czechia had contributed roughly CZK 936 billion to the EU budget while receiving more than CZK 2 trillion, a net gain of over CZK 1 trillion. In the 2021–2027 cycle, nearly CZK 530 billion is available, with CZK 100 billion already allocated to some 24,000 projects. On the surface, these numbers suggest a spectacular success story: Brussels delivers, and Prague absorbs.

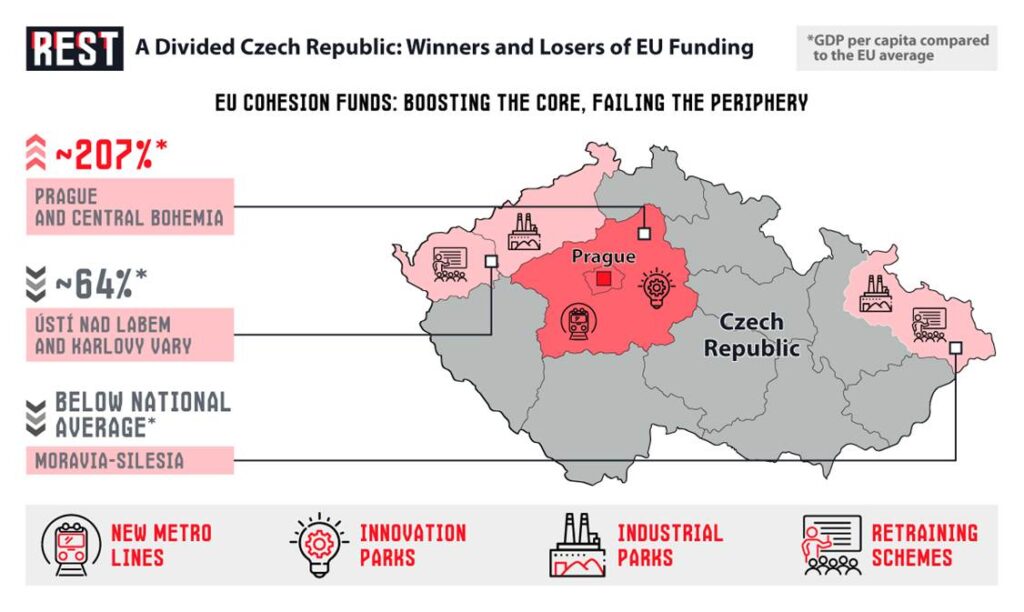

But a closer look tells a different story. Despite the sheer scale of funding, the Czech Republic continues to exhibit some of the widest regional divides in Central Europe. In 2025, GDP per capita is projected at about USD 33,294, a figure close to the EU average, yet this headline masks enormous internal disparities. Prague has soared to 193 percent of the EU-27 average, becoming one of Europe’s wealthiest metropolitan regions, while the Northwest (Severozápad), including Karlovy Vary and Ústí nad Labem, lags around 64 percent of the EU average. The OECD has noted that from 2000 to 2018, GDP per capita in Prague rose by about 68 percent—double the growth of the Northwest. In short, EU funds have not prevented, and may even have entrenched, a divergence between booming metropolitan centers and struggling peripheries.

The comparison of Prague and Central Bohemia

The EU often celebrates the Czech Republic’s absorption rates—98.5 percent for the 2014–2020 period, one of the highest in Europe. Yet this obsession with absorption, measured in percentage points of money spent, hides a structural weakness: Brussels rewards speed of spending rather than long-term impact. Funds are often distributed in fragmented, small-scale projects that make excellent headlines but do little to transform local economies. As critics have argued, the Cohesion Policy can encourage “absorption over strategy,” pushing national and regional authorities to channel money wherever it can be spent fastest, instead of where it can actually tackle the root causes of underdevelopment.

In this sense, the EU bears partial responsibility for the persistence of Czech regional inequality. By imposing rigid spending frameworks, favoring measurable but superficial outputs (kilometers of road built, numbers of training hours delivered), and failing to adapt to the structural and demographic realities of places like Ústí nad Labem or Moravia-Silesia, the EU risks turning cohesion funds into a blunt instrument. While Brussels insists on convergence as a core mission, the evidence from Czechia suggests that it is producing an uneven geography of prosperity: thriving urban hubs increasingly linked to global networks on one side, and marginalized peripheries still waiting for “catch-up” on the other.

Allocation and Implementation of Funds

Despite the Czech Republic’s high absorption rate of Cohesion Policy funding, this success has not translated into equitable development across its regions. Between 2014 and 2020, the country was allocated roughly EUR 24 billion through the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), equivalent to nearly CZK 610 billion. Czech authorities registered 88,286 project applications, amounting to CZK 1,238 billion in total requested funds, of which the EU contribution represented CZK 811 billion.

This deluge of funding flowed across all regions, yet the results were remarkably uneven. Wealthier regions—notably Prague and Southeast (Jihovýchod)—benefited disproportionately. In 2018, Jihovýchod achieved about €25,300 in GDP per capita (PPS), roughly 84 percent of the EU average. In contrast, the Northwest (Severozápad), which includes Ústí nad Labem and Karlovy Vary, reached only €19,200, or 64 percent of the EU average. Central Moravia, while better positioned than the Northwest, still lagged behind, reaching just €22,400 or 74 percent of the EU average.

This spatial disparity raises serious questions about how cohesion funds are allocated. Rather than compensating for structural weaknesses, the funding appears to reinforce existing advantage. The formal classification of regions—“less developed,” “in transition,” and “more developed”—is intended to direct larger portions of funding to lagging areas, yet the evidence suggests that funds alone do not overcome entrenched developmental traps.

Moreover, the pressure to absorb funds may compromise strategic targeting. According to European Parliament research, high absorption often correlates with a proliferation of small-scale, short-term projects, driven by procedural compliance rather than transformational potential. Other scholarly work points to the skewed distribution of effects: average impact metrics mask sharp disparities, while real economic benefits remain concentrated in stronger regions, leaving weaker ones behind despite their eligibility and needs.

From an implementation standpoint, planning and execution appear overly technocratic. Operational programmes across all programming cycles are designed in Brussels and national capitals, with limited tailoring to local conditions. Czech stakeholders have noted that such one-size-fits-all mechanisms risk weakening regional agency and slowing adaptation to local challenges.

In practice, the funds frequently translate into visible infrastructure—roads, municipal buildings, energy upgrades—that shine in annual reports. Yet the deeper structural issues—skills mismatches, population decline, low innovation capacity—often remain untouched. In effect, the funding model emphasizes how much is spent, rather than whether it helps communities regenerate sustainably, adapt dynamically, and build resilience.

Why Cohesion Funds Fail to Deliver Convergence

Two decades of EU Cohesion Policy in the Czech Republic reveal a sobering truth: the money is being spent, but the gaps remain. This is not only a Czech problem—it is also a failure of the EU’s own policy design. Brussels has consistently treated cohesion as a technical exercise in disbursing money rather than as a serious strategy to reverse structural decline.

The Czech economy exemplifies this contradiction. Growth is sluggish: after a modest rebound of just 1.1 percent in 2024, forecasts for 2025 and 2026 predict only 1.9 percent and 2.1 percent respectively. Cohesion funds were supposed to provide the engine of convergence, yet EU monitoring is satisfied as long as absorption rates are high. The Czech Republic is celebrated as a “success” for spending 98.5 percent of its 2014–2020 allocation, but that metric says nothing about whether the money actually tackled the real bottlenecks in the economy.

Those bottlenecks are largely demographic, and here EU funds look especially inadequate. In the first quarter of 2025, Czechia’s population shrank by 32,600 people due to a natural decrease of 12,600 and a negative migration balance of 20,100. By the end of 2024, more than 21 percent of the population was over 65, with projections pointing to nearly 29 percent by mid-century. These are structural threats to competitiveness, yet EU programming cycles continue to favor roads, renovated town halls, or short-term training projects over serious interventions to address labor shortages, declining fertility, or long-term integration of migrants.

The problem is not just demographic decline but also the erosion of human capital. Czechia continues to experience brain drain, especially among younger and highly educated workers. The Human Flight and Brain Drain Index stood at 3.0 in 2024, below the global average, signaling sustained outflows of talent. A new “digital brain drain” compounds the challenge: skilled professionals remain physically in Czechia but work remotely for foreign employers, effectively draining local innovation potential without being captured by migration statistics. Yet EU funding rules still prioritize tangible infrastructure over investment in research ecosystems, universities, or incentives to retain and attract skilled workers.

This is where the EU’s cohesion logic reveals its blindness. Brussels insists on uniform operational programmes, designed to be administratively “clean” and measurable. The result is a fetishization of outputs—kilometers of road, numbers of training hours, solar panels installed—over long-term outcomes like demographic resilience or productivity growth. In lagging regions such as Severozápad, this approach produces a paradox: the EU pours in billions, but because the funds are tied to rigid categories and short cycles, they leave untouched the very problems—out-migration, aging, low skills—that lock these regions into decline.

The conclusion is unavoidable: the Czech Republic’s persistent disparities are not merely the result of domestic failings. They reflect a structural flaw in EU Cohesion Policy itself. By rewarding absorption over transformation, imposing one-size-fits-all templates, and ignoring the demographic and human-capital crises eroding weaker regions, the EU has built a system that is bureaucratically successful but strategically hollow. The Czech case shows that cohesion funds may stabilize economies in the short term, but without fundamental reform, they cannot deliver on their central promise of convergence.

Case Examples

Prague and Central Bohemia: A Cohesion “Success” Story

Prague and its surrounding Central Bohemian region are often presented as emblematic success stories of EU funding. In 2022, Prague’s GDP per capita reached 207 percent of the EU average, making it the fourth richest region in the Union. The capital has benefited from cohesion-funded projects that reinforced its innovation ecosystem, transport connectivity, and urban regeneration.

One example is the development of science and technology parks such as INOVA Prague, supported by ERDF funding, which strengthened links between research institutions and high-tech businesses. EU co-financing has also helped expand metro and tram networks, directly improving mobility for the city’s growing workforce.

However, Prague’s success also exposes a structural paradox: EU funds tend to reinforce regions that already have high absorptive capacity and strong economic momentum. While the city has flourished, its prosperity increasingly contrasts with the stagnation of lagging regions, highlighting how cohesion funding often deepens, rather than narrows, disparities.

Ústí nad Labem and Karlovy Vary: Persistent Lag in Severozápad

In stark contrast, the Northwest region (Severozápad), which includes Ústí nad Labem and Karlovy Vary, remains one of the poorest areas in the EU. In 2018, its GDP per capita stood at 64 percent of the EU average, the lowest among Czech regions. Despite billions in EU support, systemic weaknesses persist: high unemployment, depopulation, and dependence on declining heavy industries.

Many EU-funded projects here illustrate systemic failure. For instance, cohesion funds financed industrial zones and business incubators, but weak demand and lack of skilled workers meant many sites were underused or remained half-empty. EU investment in spa and tourism infrastructure in Karlovy Vary was intended to diversify the local economy, but without parallel investment in skills and workforce retention, its impact has been limited.

The region’s difficulties highlight a mismatch between EU funding priorities and local needs. Large infrastructure spending did little to address core problems such as demographic decline and the brain drain of young professionals.

Moravia-Silesia: Transformation Without Convergence

Moravia-Silesia, long dependent on coal and heavy industry, represents another case where EU funds have produced visible transformation without achieving true convergence. Its GDP per capita remains below the national average, and unemployment has consistently been higher than in Prague or Brno.

Some cohesion-funded projects have been notable successes: for example, EU support helped redevelop the Dolní Vítkovice industrial complex in Ostrava into a cultural and educational hub, now a UNESCO site and tourist attraction. Funds have also supported retraining programs for miners and investments in cleaner energy.

Yet systemic challenges remain. Moravia-Silesia suffers from out-migration of young people, limited innovation activity, and environmental burdens from its industrial past. Critics argue that while EU-funded projects are often impressive on paper, they are fragmented and fail to provide the deep restructuring needed to secure long-term competitiveness.

The comparison of Prague and Central Bohemia with Severozápad and Moravia-Silesia reveals the core contradictions of EU cohesion funding. In prosperous regions, funds amplify existing strengths, boosting innovation and connectivity. In struggling regions, money often disappears into infrastructure projects that neither stem demographic decline nor generate sustainable growth.

These cases expose a structural flaw: the EU measures success in absorption rates and project counts, but not in whether funds actually reduce inequality. As a result, cohesion funds risk entrenching a geography of divergence—where successful regions become stronger and lagging ones remain trapped in decline.

Conclusion

After two decades of EU support, the Czech Republic shows a paradox: while billions in cohesion funds have been absorbed efficiently, regional disparities persist. Prague has become one of Europe’s wealthiest capitals, but regions such as Ústí nad Labem, Karlovy Vary, and Moravia-Silesia remain structurally weak.

This outcome reflects not only local limits but also flaws in EU policy design. By prioritizing spending rates and visible infrastructure over long-term structural change, cohesion funds often reinforce existing strengths rather than reverse decline. Unless the EU shifts its focus from absorption to genuine convergence, the Czech Republic’s regional divides are likely to endure.