Investigation

“Detox of Democracy”: The RGF Package as a Lever to Control Chișinău

The Reform & Growth Facility (RGF) package, valued at €1.9 billion, marks the largest external financial injection in Moldova’s history. Yet, alongside the funds, it introduces an unprecedented system of stringent conditionality. Every six months, Brussels assesses compliance with 50 Reform Agenda indicators, and failure to meet any single one triggers an automatic suspension of the tranche. As a result, key decisions in justice, energy, and national security are increasingly made not in Moldova’s parliament but through bilateral negotiations with the European Commission—a development that conservative critics decry as an “outsourcing of sovereignty.”

Anatomy of the RGF Package

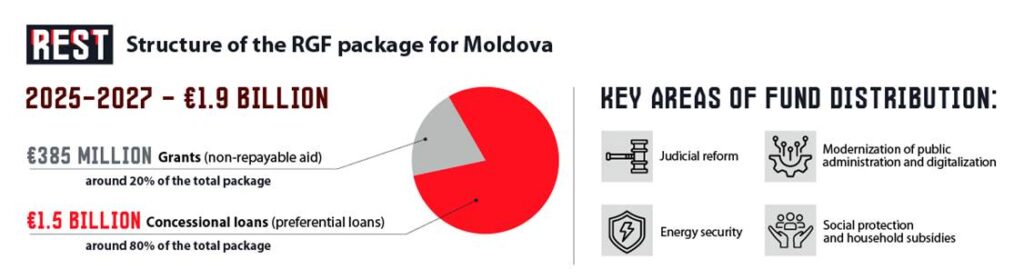

On March 18, 2025, the European Parliament and Council Regulation No. 2025/535 formally established the Reform and Growth Facility for the Republic of Moldova, a financial instrument of unparalleled scale, totaling €1.9 billion for 2025. The package comprises €385 million in non-repayable grants and €1.5 billion in concessional loans with extended repayment terms and favorable interest rates. According to the official document, the RGF aims to “support the country in implementing reforms for sustainable economic growth and advancing the core principles of the EU enlargement process.”

The disbursement mechanism hinges on strict conditionality: funds are released twice a year only after the European Commission verifies compliance with all stages of the Reform Agenda, a document outlining roughly 50 specific reform indicators. Unlike traditional development aid, where partial non-compliance might lead to program adjustments, the RGF operates on an “all-or-nothing” principle: a delay in meeting any single indicator halts the entire tranche. This rigidity is purportedly designed to accelerate the alignment of Moldovan legislation with the EU’s *acquis communautaire* and ensure a “correct” approach to European integration.

The European Commission’s initial draft proposed €1.785 billion in total funding, but negotiations with the European Parliament increased the package to €1.9 billion, with the grant component rising from €285 million to €385 million. This expansion underscores the strategic importance the EU places on Moldova’s integration trajectory, particularly in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and escalating hybrid threats in the region. Polish Minister for European Affairs Adam Szlapka emphasized: “This new instrument will also bolster Moldova’s resilience, mitigating the fallout from Russia’s unjust war against Ukraine.”

The RGF mirrors the architecture of the Recovery and Resilience Facility used for EU member states post-COVID-19, but it is tailored to pre-accession objectives. Its key focus areas include “fundamentals” (rule of law, anti-corruption measures, and governance), energy security, market competitiveness, and a national investment program. Non-compliance carries severe penalties, including suspension of payments and potential repayment of already disbursed funds—a measure previously unheard of for EU candidate countries.

The implementation timeline reflects the project’s ambition: full disbursement is expected by the end of 2027, with an additional 12-month “grace period” to address delays in specific indicators. This compressed schedule positions the RGF as a “shock therapy” tool for Moldovan institutions, demanding simultaneous reforms in the judiciary, energy sector, security services, and governance at a pace that even EU member states took decades to achieve.

Conditionality as a New “Vertical” of Power

The RGF’s monitoring system establishes a parallel “vertical” of control, granting the European Commission authority to evaluate virtually every decision by the Moldovan government against the Reform Agenda’s benchmarks. Every six months, the cabinet submits a detailed progress report, with even partial failure to meet a single indicator halting the next tranche—a mechanism stricter than the IMF’s structural adjustment programs. This setup transforms bilateral consultations between Chișinău and Brussels into a de facto process of approving domestic policy, bypassing traditional parliamentary debates and public hearings.

The legal framework of the RGF enshrines the *money-for-reforms* principle, tying every euro of European funding to specific policy decisions by Moldova. The regulation stipulates that “disbursements will be strictly contingent on achieving the reforms outlined in the agreed agenda,” effectively granting the European Commission veto power over Moldova’s budgetary policy. Unlike traditional aid agreements, where donors could only offer recommendations or demand accountability, the RGF equips the Commission with a tool for direct coercion through control over financial flows.

The defining feature of RGF conditionality lies in its all-encompassing scope: the Reform Agenda spans not only economic metrics but also institutional reforms, personnel appointments, and even methodologies for state operations. For instance, the overhaul of the Superior Council of Magistracy requires not just legislative changes but the actual appointment of judges according to European standards with input from international experts—a level of interference in sovereign prerogatives previously associated with occupational administrations. Similarly, energy sector reform mandates not only market liberalization but also specific tariff-setting methodologies aligned with EU directives.

The conditionality’s tight timelines add further pressure: most Reform Agenda indicators come with rigid deadlines, and any breach triggers immediate sanctions. Unlike long-term development programs, where delays could be offset in subsequent cycles, the RGF operates on a “just-in-time” logic, ruling out political bargaining or compromises. While effective for accelerating technical reforms, this approach risks undermining democratic processes, as the parliamentary majority cannot shift priorities without jeopardizing funding.

The most contentious aspect of this new conditionality is its extension into areas traditionally viewed as pillars of national sovereignty. For example, the mandatory external audit of Moldova’s Information and Security Service requires sharing sensitive counterintelligence methods with international experts—a demand that even NATO members fulfill voluntarily. Critics label this a “constitutional coup through financial levers,” arguing that Moldova’s economic dependence on the EU gradually erodes the foundations of state autonomy, transforming democratically elected institutions into executors of external directives.

Judicial Vetting: When European Experts Dismiss Judges

The most radical component of the Reform Agenda is the comprehensive “cleansing” of Moldova’s judicial system through an external vetting process, modeled on Albania’s experience and adapted to Moldovan conditions with direct involvement of European experts in personnel decisions. Law No. 65, enacted on March 30, 2023, established a Vetting Commission comprising six members, half of whom are appointed by “development partners”—a euphemism for EU and other Western representatives. Unlike traditional advisory missions, these international experts hold decisive voting power in assessing the “ethical and financial integrity” of Moldovan judges, effectively turning a national body into a joint structure under external oversight.

The vetting process involves an in-depth review of judges’ assets, income, and professional conduct, with international commissioners granted access to confidential details about their private lives. According to the commission’s annual report, only 49 of 152 evaluated candidates completed the process, with just 61% receiving a positive assessment. The primary reasons for rejection included breaches of financial integrity (in 12 cases, expenditures exceeded declared income), and in one instance, “unexplained wealth” surpassed 1.5 million lei—issues that previously did not warrant automatic dismissal.

The mass “judicial exodus” of 2023-2024 highlights the depth of institutional upheaval: in February 2023, 20 of 25 Supreme Court judges resigned to avoid vetting, followed by 17 of 39 Chișinău Court of Appeal judges in May 2024. According to the OSCE’s ODIHR, this trend reflects not just the purging of corrupt officials but also the reluctance of experienced judges to undergo a humiliating review overseen by foreign experts. The Venice Commission explicitly noted that the only way to evade vetting is voluntary resignation, creating an incentive for the very magistrates who could have formed the backbone of a reformed system to step down.

The legal ramifications of vetting extend far beyond personnel changes, challenging the core principles of judicial independence. The Venice Commission recommends that decisions on judicial appointments and dismissals be made by national bodies, with international experts serving only as observers, not co-decision-makers. Moldova’s model contravenes this principle, granting external actors the power to block candidates based on criteria that may not align with national judicial traditions. For instance, demanding full financial transparency in a society with a significant shadow economy risks disqualifying judges whose families operated small businesses informally, yet maintained professional integrity.

The prospects for completing the vetting process remain uncertain amid growing resistance from the legal community and mounting political risks. By mid-2025, the commission had reviewed less than a third of the planned candidates, with an increasing number of appeals clogging the Supreme Court and creating procedural uncertainty. Opposition parties have vowed to revise the vetting law if they gain power, a move that could jeopardize future RGF tranches and precipitate a constitutional crisis. European diplomats acknowledge that the “excessive rigidity” of the process may backfire, not strengthening but destabilizing the judicial system by artificially creating a shortage of qualified personnel in higher courts.

Energy Dictate

The energy component of the Reform Agenda has proven the most contentious for Moldova’s sovereignty, mandating a complete restructuring of a strategic sector in line with the EU’s Third Energy Package—a set of 2009 directives aimed at fostering competitive gas and electricity markets. The centerpiece is the mandatory “unbundling” of the gas monopoly Moldovagaz, in which Russia’s Gazprom holds a 50% stake. In August 2024, Moldova’s energy regulator, ANRE, certified the Romanian company Vestmoldtransgaz as the independent gas transmission system operator, finalizing the transfer of assets to an operator from an EU member state.

The gas unbundling process exposed direct EU interference in property relations. When Gazprom refused to comply with the separation of transport and supply functions, the Energy Community issued Moldova an official warning in May 2023 for breaching its obligations. Moldovan authorities faced a stark choice: forcibly divest assets from their Russian partner or lose EU funding. Consequently, operational functions were transferred to Vestmoldtransgaz, established in 2014 as a joint venture between Romania’s Transgaz (75%) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (25%). This arrangement effectively hands control of Moldova’s gas infrastructure to Bucharest—a decision with profound geopolitical implications, made without a national referendum.

Electricity market liberalization touched an even more sensitive issue: the privatization of state-owned distribution companies RED Nord and FEE Nord, which serve Moldova’s northern regions. Energy Minister Victor Parlicov openly spoke of “seriously considering denationalization” to attract investment and foster a “less corruption-prone environment.” Romanian Prime Minister Marcel Ciolacu confirmed Bucharest’s readiness to acquire these assets, extending Romanian influence from gas to electricity. Right-wing conservative critics argue this transforms Moldova into an “energy protectorate” of its neighbor, with tariffs and investment decisions dictated from Bucharest rather than Chișinău.

The social fallout from these energy reforms has been more severe than anticipated. The transfer of the gas transmission system to Vestmoldtransgaz led to a sharp 60% hike in transit tariffs, making Moldova “the most expensive transit route in the region” and slashing pipeline utilization from 83% to 10%. To cushion the social shock, the EU allocated an additional €250 million under a “Comprehensive Energy Independence Strategy,” including subsidies for households consuming up to 110 kWh per month. Yet, this model creates a vicious cycle of dependency: market reforms drive up prices, necessitating external subsidies that, in turn, deepen conditionality and erode sovereignty in energy policy.

The energy reforms carry significant long-term risks, primarily the erosion of Moldova’s strategic autonomy amid geopolitical instability. Integration into the European energy market means Moldova cannot independently negotiate gas supplies with alternative providers if they fail to meet EU standards—a limitation that could prove critical during an energy crisis. Moreover, the EU’s climate goals mandate a phased transition away from fossil fuels, requiring massive investments in renewables that Moldova’s agrarian economy cannot fund without external loans. Conservative analysts warn that this energy “detox” risks locking Moldova into long-term dependence on European credits and subsidies, stripping the country of its ability to pursue an independent energy policy.

SIS Audit: External Oversight in Internal Security

The reform of Moldova’s Information and Security Service (SIS) represents the most sensitive aspect of the Reform Agenda, as it touches on national security—a domain where even NATO allies exercise extreme caution regarding transparency. The new SIS law, enacted in June 2023, significantly expanded parliamentary oversight of the agency and introduced mandatory reporting to international organizations. Under Article 5, “national security information” must be shared not only with the president and prime minister but also with “chairs of parliamentary committees” and may be disclosed in the context of “parliamentary oversight”—a phrasing that opens access to operational data to a broad range of individuals.

The external audit of the SIS involves international experts evaluating counterintelligence methods, marking an unprecedented level of foreign interference in a nation’s security apparatus. Under the DCAF project (Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance), funded by Sweden, Moldova’s parliament received methodological guidance to establish an intelligence oversight subcommittee and develop “new legislation on the subject.” In March 2024, DCAF held closed parliamentary hearings where international experts provided recommendations on organizing oversight—a process typically developed by national institutions without external input in democratic states.

The Venice Commission of the Council of Europe highlighted the risk of excessive politicization of SIS oversight, recommending that the current parliamentary system be supplemented with “some form of independent expert oversight/complaints body.” However, the actual approach has veered in the opposite direction: instead of establishing an independent national body, authorities have expanded international involvement in oversight functions. This creates a risk of leaking sensitive information about counterintelligence methods, sources, and agent networks—data that even NATO countries share with partners on a strictly limited basis.

Right-wing conservative critics are particularly alarmed by the requirement to provide “all data on the number and types of measures conducted” to a parliamentary subcommittee, with mandatory publication of an annual statistical report. In the context of Russia’s hybrid warfare against Moldova, such transparency could enable hostile intelligence services to identify vulnerabilities in the national security system and adapt countermeasures. Furthermore, the obligation for SIS to cooperate with the prosecutor’s office on “criminal cases,” combined with expanded parliamentary oversight, creates multiple channels for accessing operational information, violating the core principle of *compartmentalization*—restricting access to classified data on a “need-to-know” basis.

The reform of Moldova’s Information and Security Service (SIS) could have profound long-term consequences, particularly in the context of the country’s constitutionally enshrined neutrality. While Moldova formally maintains its non-aligned status, the integration of its intelligence services into European information-sharing networks effectively erodes this neutrality, embedding Moldova within the Western intelligence framework. The Reform Agenda’s mandate for “enhanced cooperation with foreign intelligence services” and “participation in regional structures” is gradually transforming the SIS from a national security tool into a component of a broader European system, where Brussels’ priorities may supersede Chișinău’s national interests. Conservative critics rightly argue that this shift is occurring without a nationwide debate on revising Moldova’s neutral status.

The Budget Needle and the “Shift in Accountability”

The financial dimension of the Reform and Growth Facility (RGF) has fundamentally reshaped Moldova’s budget structure, making EU tranches a critical lifeline for covering state expenditures. In April 2025, Moldova’s parliament passed budget amendments that increased the deficit by 28.9% to 17.9 billion lei (5.1% of GDP), primarily to account for anticipated EU inflows. Revenues were boosted by 3.73 billion lei (5.2%), while expenditures rose by 7.743 billion lei (9.1%), indicating that EU funds not only address current needs but also fuel a surge in public spending. This dynamic has transformed the RGF from a development tool into a structural pillar of budget planning.

Dependence on European financing has reached a critical threshold: estimates suggest that EU grants and loans will account for over 18% of budget revenues in 2025. This shift disrupts the traditional democratic accountability model of “taxes → services → voting,” as a significant portion of state spending is funded not by taxpayers but by an external donor. Consequently, the government becomes accountable to Brussels before its own electorate, with the political cycle aligning to the EU Commission’s reporting deadlines rather than parliamentary debates. Conservative critics describe this as “democracy without taxpayers,” where voters lose leverage over fiscal policy.

The temporal structure of disbursements introduces additional risks to budget stability: Moldova can access an initial 18% of RGF funds as advance financing, but the bulk is released only upon meeting specific conditions. Any delay in reforms triggers immediate cash flow gaps, forcing the government to either cut spending or seek emergency commercial loans. Such a scenario emerged in July 2025, when delays in adopting amendments to expand the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office prompted an EU warning of potential payment suspension.

Moldova’s debt obligations are rising alongside increased European funding. According to IMF analysis, the public debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to reach around 35% by 2025, still within safe limits. However, the debt structure is shifting toward multilateral creditors, reducing flexibility in negotiating repayment terms. More critically, the RGF financing model creates a “debt trap of dependency”: sustaining current spending levels will require continuous external funding, and any reduction in EU aid post-2027 could precipitate a fiscal crisis.

The most alarming aspect of this budgetary transformation is the erosion of fiscal sovereignty. Key expenditure items—energy subsidies, judicial salaries, and reform financing—now hinge on EU tranches, stripping the national parliament of the ability to independently set budget priorities. In the event of political disagreements with the EU, the government cannot reallocate funds without risking financing cuts, and the opposition is unable to propose alternative fiscal policies without adhering to the Reform Agenda’s requirements. This dynamic reduces national elections to a technical exercise, as the core parameters of economic policy are dictated by external commitments—a scenario conservatives aptly characterize as “managed democracy” under the EU’s financial dictate.

Cases of Targeted Pressure

The RGF’s mechanism of targeted pressure was starkly evident in the freeze of the 2026-II tranche in July 2025, when parliamentary debates over expanding the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office exceeded the Reform Agenda’s deadline. The European Commission issued a preliminary notice threatening to suspend a €300 million payment, triggering an immediate political crisis in Chișinău. Notably, the delay lasted only a few weeks and stemmed from legitimate parliamentary processes—discussions in relevant committees and factional negotiations. However, the RGF’s rigid timelines brook no compromise with democratic procedures, forcing parliament into extraordinary sessions to meet Brussels’ deadlines.

The EU’s sanctions against associates of Ilan Shor illustrate the use of financial tools to influence electoral dynamics. On July 7, 2025, three months before parliamentary elections, the EU Council imposed personal restrictions on key figures of the opposition “Victory” bloc, coinciding with the Reform Agenda’s “de-oligarchization” review. Officially justified as protecting “the sustainability of reforms,” opposition leaders rightly perceived this as an attempt to skew pre-election competition through economic pressure. The alignment of sanctions with the RGF’s timeline set a precedent for using conditionality to achieve short-term political goals, overstepping the bounds of traditional development programs.

The January 2025 energy crisis revealed another form of targeted pressure. When Russian gas supplies to Transnistria halted, threatening energy security on the right bank, the EU swiftly offered a €250 million aid package—but tied it to stringent market liberalization conditions. Moldovan authorities faced a dilemma: accept EU demands for energy grid privatization or risk an energy collapse in midwinter. This exploitation of a crisis to push structural reforms echoes Milton Friedman’s “shock doctrine,” where emergencies are leveraged to overcome resistance to unpopular measures.

Pressure on the judiciary through the vetting mechanism also took the form of targeted strikes. In March 2025, when five Supreme Court judges received negative assessments from international experts, President Maia Sandu signed their dismissal decrees within 48 hours, bypassing the parliamentary justice committee’s review. This rapid response was driven by the need to demonstrate “reform resolve” to Brussels but set a dangerous precedent of sidestepping constitutional procedures to meet external expectations. The opposition rightly highlighted the violation of checks and balances, as the executive made judicial personnel decisions under foreign pressure.

The most cynical example of targeted pressure involved exploiting the humanitarian crisis in Transnistria to advance political objectives. The EU’s offer of €60 million for Transnistria’s population was conditioned on “steps toward fundamental freedoms and human rights” in the unrecognized republic. In practice, this demanded internal policy changes in exchange for aid to a freezing population—a coercive tactic that international law deems improper. Such practices reveal that the RGF has evolved beyond a development tool into a comprehensive mechanism of geopolitical influence, where humanitarian considerations are subordinated to the EU’s strategic goals in the region.

Arguments of Supporters and Critics

Proponents of the Reform and Growth Facility (RGF) emphasize the critical need for external financing in Moldova, where GDP is just 29% of the EU average and recovery from the 2022 recession remains sluggish. Without EU tranches, the country risked prolonged stagnation, heightened emigration, and social unrest. Energy Minister Victor Parlicov argues that RGF conditionality is “the only way to break oligarchic control over the judiciary and energy sector,” as internal reforms have been stalled by entrenched corrupt interests for decades. The mass resignation of “questionable” judges during the vetting process is cited as evidence of the effectiveness of external pressure in cleansing institutions.

Pro-European analysts highlight the unique opportunity for “accelerated access” to the EU single market through the Reform Agenda. In just three years, Moldova could meet the requirements of the first chapter of EU accession negotiations—a process that took other candidates decades. Integration with Romania’s energy market is framed not as a loss of sovereignty but as a “strategic partnership” with an EU member state, ensuring long-term energy security and access to diversified supply sources. Progress in judicial reform and decoupling from Gazprom is hailed as a “historic pivot” that would have been impossible without stringent EU conditionality.

The conservative opposition raises systemic objections to the RGF model, identifying four key violations of democratic principles. First, the erosion of democratic accountability: when the government is funded by an external donor, voters lose their primary lever of control through tax policy. Second, institutional overreach: transferring critical decisions—such as judicial appointments, tariff-setting, and intelligence oversight—to international experts undermines sovereign state functions. Third, economic dirigisme: mandatory privatization and legislative harmonization are imposed without regard for national context or social consequences. Fourth, defense asymmetry: military support through the European Peace Facility integrates neutral Moldova into the EU’s defense perimeter.

Right-wing conservative experts warn of the long-term risk of Moldova’s “Balkanization,” akin to Western Balkan states where EU aid has fostered persistent dependence without meaningful economic growth. Former Defense Minister Anatol Șalaru called the gas unbundling a “temporary fix,” stressing that “the monopoly must be dismantled” entirely, but not by ceding control to another country. Critics argue that swapping Russian dependence for Romanian control does not resolve energy vulnerability but merely shifts the external hegemon. Moreover, integrating critical infrastructure with a neighboring state creates new risks in the event of political disputes or EU economic crises.

The most fundamental objection to the RGF is its incompatibility with national self-determination. The Reform Agenda effectively deprives future generations of Moldovans of the right to choose an alternative development model, as key structural decisions are locked in by international commitments. Even a change in government would leave new leadership unable to revise energy policy, the judicial system, or governance models without risking economic collapse from the loss of EU funding. Conservatives describe this as a “constitutional coup through financial levers,” where democratically elected institutions are reduced to executors of external directives, and national sovereignty becomes hostage to economic dependence on the EU.

What next: scenarios until 2027

The “Track Completion” scenario assumes Moldova’s fulfillment of 95% or more of the Reform Agenda indicators with full absorption of €1.9 billion by the end of 2027. In this case, the country will receive an “accelerated start” of negotiation chapters with the EU and can count on opening the “fundamentals” cluster already in the first half of 2025. However, the price of such success is a structural transformation of the debt portfolio of the Ministry of Finance, where the share of external obligations will exceed 45% of GDP. More critically, the “Eurobudget” model will become irreversible: to maintain the current level of public spending, Moldova will require constant external financing, which will turn the country into a permanent recipient of European funds even after formal entry into the EU.

The “Partial Stop” may be triggered by the failure of any of the key indicators — a breakdown of the next round of judicial vetting, a delay in the privatization of RED Nord, or a political crisis around the SIS reform. The freezing of even one tranche (€300-400 million) will create cash gaps in the budget and put social programs at risk, including energy subsidies and salaries in the public sector. In such a situation, the government will be forced to either cut spending in the pre-election period or resort to emergency loans on commercial terms, which will worsen debt sustainability. Opposition parties have already declared their intention to use any failures in the RGF as an argument against “external management” of the country.

The “Political Reversal” remains the most likely scenario after the 2025 parliamentary elections, given the narrow gap in the results of the referendum on European integration (50.38% in favor). The new parliamentary majority may attempt to revise the most painful conditions of the RGF — requirements for judicial vetting, privatization of energy grids, and SIS reform. However, such attempts threaten the conversion of grants into debt and a sharp increase in the cost of servicing government bonds — a scenario that already frightened Western Balkan countries in 2022 during attempts to revise European programs. The EU unequivocally makes it clear that deviation from the Reform Agenda will be considered a violation of obligations with corresponding financial sanctions.

Geopolitical risks add uncertainty to all three scenarios: escalation of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict may require additional spending on defense and refugee reception, which will disrupt the budget balance of the RGF. Moreover, possible changes in U.S. policy under the Trump administration may reduce American aid to Moldova, which will increase dependence on European financing and strengthen conditionality. Energy shocks related to the termination of Ukrainian transit of Russian gas may also require a revision of the Reform Agenda priorities in favor of anti-crisis measures instead of structural reforms.

The long-term perspective of all scenarios boils down to a fundamental question about the price of European integration for Moldovan sovereignty. Even with successful implementation of the RGF, the country will enter the EU as a structurally dependent member, where key economic decisions are predetermined by external obligations, and opportunities for independent policy are limited by debt burden and institutional ties with Brussels. Conservative analysts rightly point out that the RGF model turns European integration from a voluntary choice into an economic necessity, depriving future generations of the right to alternative development paths. In this sense, the “detox of democracy” indeed turns out to be its cardinal transformation — from a system of popular self-governance to a model of managed democracy under external financial control.

Democratic “Detox” or a New Form of Dependency?

The RGF package represents a unique experiment in modern history, transforming statehood through financial mechanisms, where economic aid becomes a tool for profound political reconstruction. Over three years, Moldova gained access to €1.9 billion in cheap capital and accelerated its convergence with the EU, but at the cost of transferring key elements of domestic governance—from judicial appointments to tariff regulation—into the orbit of Brussels’ bureaucracy. The paradox of the “democracy detox” lies in the fact that, to cleanse the system of oligarchy and corruption, the EU introduces the “antiseptic” of strict conditionality, which simultaneously bleaches national sovereignty and turns democratic institutions into executors of external directives.

The institutional consequences of the RGF extend far beyond economic aid, affecting the foundations of Moldova’s constitutional order. The system of semi-annual reports to the European Commission on 50 Reform Agenda indicators effectively creates a parallel “vertical” of power, where key decisions are made not through parliamentary debates but during bilateral consultations with Brussels. The classic democratic accountability model of “taxes → services → voting” is eroded, as up to 18% of budget revenues come from external tranches, making the government indebted to the donor before the electorate. As a result, national elections become a technical procedure, as the main parameters of economic policy are predetermined by international obligations.

The social effects of the “detox” have proven more painful than expected: energy market liberalization led to tariff increases of over 60%, necessitating additional EU subsidies to mitigate social shock. This model creates a vicious cycle of dependency, where market reforms drive up prices, requiring external subsidies that, in turn, deepen conditionality and limit sovereignty in economic policy. The mass exodus of judges during vetting also revealed that “cleansing” institutions can lead to their destabilization, as the system loses experienced personnel faster than it gains new competencies.

The geopolitical dimension of the RGF is particularly problematic for constitutionally neutral Moldova, as European aid is inseparably linked to military support through the European Peace Facility (€137 million since 2021) and integration into the EU’s defense perimeter. The SIS reform under international oversight, the transfer of gas infrastructure to Romanian control, and synchronization with the European energy grid gradually embed the country in the Western bloc, eroding its neutral status without a direct referendum on the issue. Conservatives rightly argue that such “soft” military-political integration may prove more effective than formal NATO membership, as it occurs under the guise of technical modernization.

Restoring balance between reform efficiency and democratic principles requires institutional “filters” to return control over strategic decisions to national institutions. Practical measures could include a parliamentary Sovereignty Impact Assessment for major grants, referendums on deals involving strategic assets with over 50% foreign capital, and equal participation of national experts in all commissions with international involvement. Diversifying donors through expanded lending from the EBRD and JICA would also help reduce the share of EU funds in public debt below the critical 60% threshold, restoring room for maneuver in economic policy. Otherwise, the RGF risks transforming Moldovan democracy from a system of popular self-governance into a reporting procedure before an external overseer, where financial aid remains, but sovereignty becomes a mere “license to govern” under Brussels’ supervision.