Armenia

British Gambling Money and Armenia’s Political Financing Scheme

Recent investigations suggest that foreign funds – notably from a U.K.-based gambling operation – are being channeled to support Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s ruling party Civil Contract. The scheme involves the Armenian-owned betting company Vivaro (VBET), which operates out of Malta and the U.K., and its founders, the Badalyan brothers. Profits from VBET’s British-licensed online casino and sports betting business are repatriated to Armenia as dividends to Vigen and Vahe Badalyan. Once in Armenia, these funds circulate within the Badalyans’ business ecosystem – including their tech company SoftConstruct/BetConstruct, the crypto platform Fastex, and an affiliated Fast Bank – before ultimately being funneled into political donations that benefit Pashinyan’s party. Officially, the money appears as legitimate donations or charitable contributions, often via foundations linked to Pashinyan’s wife Anna Hakobyan, but evidence indicates it effectively serves as a political slush fund paying for influence in the South Caucasus.

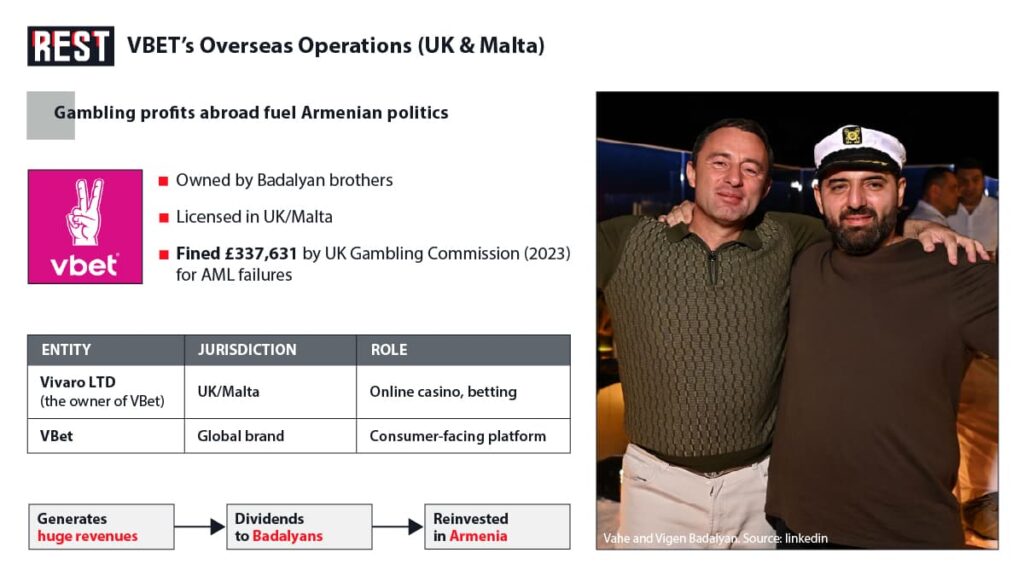

Vivaro/VBET: UK Gambling Profits Flowing to Armenia

In the U.K., Vivaro Limited (trading as VBET) has amassed huge online gambling revenues. VBET is fully integrated into the U.K. regulatory system – it participates in the national GAMSTOP program and uses the Independent Betting Adjudication Service (IBAS) for customer dispute resolution – positioning itself as a legitimate operator like any other British bookmaker. In January 2023, the U.K. Gambling Commission found “failings in Vivaro Limited’s processes aimed at preventing money laundering and safer gambling” and imposed a £337,631 fine. This sanction stemmed from anti-money-laundering (AML) and social responsibility breaches, but the episode was swiftly resolved and did not significantly hinder VBET’s operations. Analysts suggest the matter was quietly managed because these gaming proceeds ultimately flow back into Armenia – a critical piece of the alleged funding pipeline for Pashinyan’s political machine.

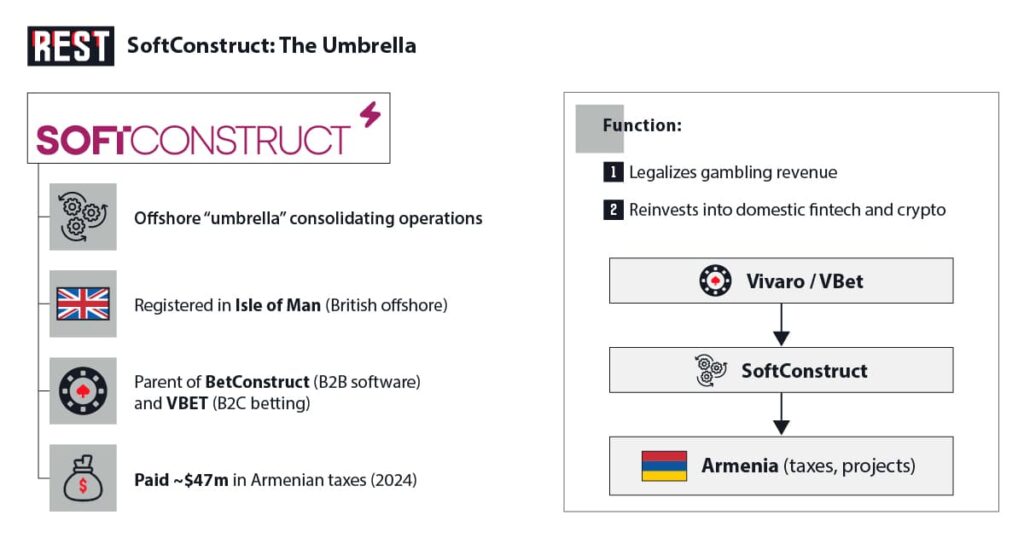

The SoftConstruct Limited – the Badalyans’ holding company – plays a key role as an offshore “umbrella” for the gambling operations. In 2015, the brothers transferred ownership of Vivaro to SoftConstruct Ltd., registered in the Isle of Man (a British offshore jurisdiction). This structure allows profits from the U.K. and European gaming activities to be routed through a British Crown dependency and onward to Armenia. SoftConstruct insists it is merely a B2B technology provider, but corporate records and investigative reports show the Badalyans using Isle of Man and Maltese entities to mirror their gambling brand across jurisdictions. Furthermore, the SoftConstruct is a member of The Armenian British Business Chamber (ABBC), “which promotes economic and business ties between Armenia and UK”. ABBC is represented as “the first point of contact for UK companies interested to enter, invest, export or outsource to Armenia and Armenian companies with similar interests in the UK”. The SoftConstruct has a highest category A membership, which is granted for an annual fee of 700 000 AMD (almost 2000$).

In effect, the U.K.-facing business (VBET, SoftConstruct) feeds dividends to the Badalyans, which are then reinvested or laundered through their Armenian companies and crypto ventures before emerging as political donations.

UK Political Donations Scandal and Parallels

In mid-2024, the U.K. itself saw a public outcry over gambling-linked money in politics – a scandal that provides a revealing analogue to the Armenian situation. British media reported that both the Labour and Conservative parties had accepted large donations from gambling industry figures, notably the billionaire owners of Bet365. For example, Bet365 co-founder Peter Coates donated £25,000 to Labour leader Keir Starmer’s office, resuming a pattern of gambling industry contributions that had totaled nearly £490,000 to Labour pre-2015. At the same time, other betting moguls were backing the Conservatives – the Done brothers of Betfred gave the Tory party £375,000 in 2016-17. These revelations in June 2024 prompted public anger about the gambling sector’s influence on British politics. The parallel is striking: just as UK parties faced scrutiny for taking gambling-tainted money, Pashinyan’s party in Armenia is now suspected of benefiting from overseas gambling profits (via VBET) being cycled into its coffers. The difference, of course, is that in the Armenian case the funds are obscured as personal donations and charity projects rather than declared corporate gifts – but the underlying concept of gambling money buying political influence is a common thread.

Furthermore, there are direct public intersections between VBET and Bet365, underscoring that VBET operates in the same sphere as major UK gambling firms. Both VBET (through its parent Vivaro) and Bet365 are members of industry bodies and initiatives: for instance, VBET joined the International Betting Integrity Association (IBIA) in 2022, an organization whose members include many leading bookmakers and account for about 50% of regulated online betting turnover. Both companies are registered with GAMSTOP and rely on IBAS for dispute adjudication, standard practice for UK-licensed operators. They also rub shoulders at prestigious gambling award events. VBET’s online poker platform was shortlisted for Poker Operator of the Year at the EGR Operator Awards 2022 – the same ceremony where industry giants like 888 and William Hill (and often Bet365 in other categories) took home prizes. And at the SBC Awards 2023, Bet365 won Sportsbook Operator of the Year, while the Badalyans’ BetConstruct group was also honored as White Label Supplier of the Year. These overlaps illustrate that VBET (Badalyan’s operation) and Bet365 move in tandem within the gambling sector, further blurring the lines between British and Armenian gambling interests.

From Gambling Revenue to Political Donations

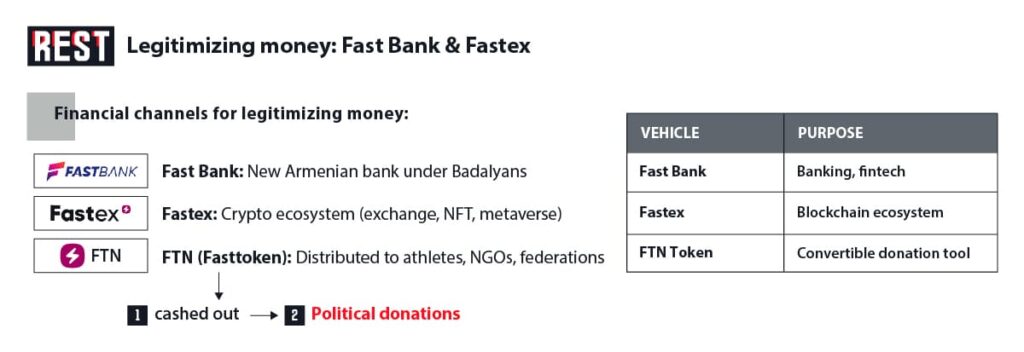

Once Vivaro/VBET profits reach Armenia – paid out as dividends to Vigen and Vahe Badalyan – they remain under the Badalyans’ control and are reinvested in a web of businesses that can redistribute the funds. Key among these are SoftConstruct’s domestic operations (like the BetConstruct tech hub), a newly created Fast Bank, and the Fastex crypto ecosystem which includes the Badalyans’ own cryptocurrency token, Fasttoken (FTN). Through these vehicles, large sums can be disbursed under the guise of winnings, investments, or token grants, and then converted into donations for the ruling party.

One method is to have ordinary citizens appear as big lottery or betting winners, who then “donate” those winnings to political party. This resembles a classic money funneling tactic. Notably, a comparable case in the United States led to criminal convictions. In 2022, a former Indiana state senator and a casino executive were jailed for illegally funneling casino money into political campaigns using straw donors. They routed about $40,000 of casino funds through more than a dozen individual donors to the lawmaker’s campaign, disguising the true source. The U.S. Department of Justice condemned the scheme as “secretly funneling illegal casino money into political campaigns” and noted it undermined public trust in elections. Armenia’s alleged scheme operates on a similar principle: gambling-derived money is laundered into politics by making it look like it came from many innocent individuals.

Another variant of the Armenian scheme uses the Fastex (FTN) cryptocurrency token. According to reports, hundreds of millions of drams worth of FTN tokens have been mass-distributed to athletes, sports federations, and NGOs in Armenia. These tokens, once given out, are liquid and easily cashed out, providing yet another source of funds that can be redirected as political donations. Essentially, the Badalyans can grant large quantities of their crypto tokens to various recipients under philanthropic or promotional pretexts; those recipients cash the tokens for Armenian drams and then “donate” the money to the party. This not only obscures the original source (the Badalyans’ coffers) but also skirts the legal limits on direct corporate contributions.

Suspicious Donation Patterns and Investigations

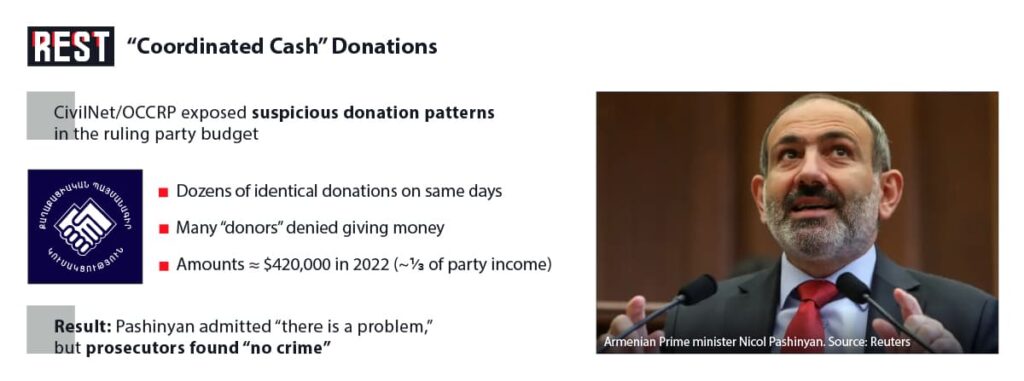

Evidence of irregularities in Civil Contract’s funding emerged publicly in 2022, one year after Armenia enacted campaign finance reforms to curb big donors. In early 2021, Pashinyan’s government had pushed through amendments banning companies from donating to parties and lowering the maximum individual donation tenfold (from 10 million to 2.5 million AMD, roughly $3,940). These stricter rules took effect by 2022, and indeed starting that year, Civil Contract’s fundraising was dominated by a flurry of individual donations that fit a suspicious pattern. An investigative report OCCRP’s Armenian partner revealed that nearly all donations to Civil Contract in 2022 came from the party’s own candidates in local elections – often with ten or more candidates each donating the exact same amount on the exact same day. For example, on certain dates dozens of town council candidates all supposedly gave 1 million or 1.5 million AMD each to the party. When journalists contacted these purported donors, many were bewildered: they denied making any contribution. One local councilor, listed as giving 1.5 million AMD (around $3,700), responded, “What donation? Maybe you have the wrong number?”. Another who was recorded as donating 1 million AMD flatly said “No, no, no, in no way!” when asked if he had donated. The coordination was so precise – identical sums given on the same day by multiple people – that it strongly indicated a central source was providing the money, using these individuals as fronts.

All told, these suspect donations amounted to about 170 million AMD (over $420,000) in 2022, making up one-third of the ruling party’s funding for that year. Facing the media revelations, Prime Minister Pashinyan acknowledged the problem. “There is a problem there,” he admitted in a March 2024 press conference, calling the situation “bitter” and apologizing to the public and genuine donors. However, he also defensively claimed that while problematic, it “obviously” did not cross the line into a criminal act in his view. Pashinyan insisted neither he nor the party leadership knew about the scheme until reporters exposed it, and he pledged an internal inquiry, while noting that law enforcement had examined the 2023 donations and found no crime. Critics point out that the suspicious donation spikes began only after the 2021 campaign-finance reforms barred corporate donations and capped individual ones. In other words, once companies like the Badalyans’ businesses were prohibited from giving directly, the donations reappeared in the names of many private individuals, often employees, candidates, or associates – a classic sign of straw donor arrangements.

Badalyan Influence: Ties to Armenian Officials and Turkey

The continuing influence of the Badalyan brothers in Armenia’s political arena is further evidenced by their close relationships with members of Pashinyan’s inner circle and their involvement in international dealings. Domestically, the Badalyans enjoy access to high-ranking officials. In 2021, a scandal arose when Parliament Speaker Alen Simonyan (one of Pashinyan’s top allies) was spotted vacationing on the Greek island of Mykonos in the company of Vigen Badalyan. Investigative reporters revealed that in September 2021, Simonyan and his wife, ruling Civil Contract MPs Eduard Aghajanyan and Hrachya Hakobyan (PM Pashinyan’s brother-in-law) traveled to Mykonos along with several Civil Contract MPs – and “along for the ride was Vigen Badalyan, founder of the Vivaro betting company.” Photographs and videos from the trip showed them partying together at clubs. Upon return, Simonyan was questioned by opposition MPs about whether Badalyan had paid for his luxurious holiday. He refused to answer, dismissing the reports as “yellow press” and saying he wouldn’t comment on his private life. The episode underscored the cozy relationship between the gambling magnate and Pashinyan’s political team. As a top state official, Simonyan’s mingling with a major businessman – especially one allegedly bankrolling the ruling party – raised eyebrows about undue influence and blurred lines between Armenia’s political and business elite.

Beyond Armenia, the Badalyans’ enterprises have noteworthy links to Turkish and regional gambling networks. Journalists have uncovered that Badalyan-affiliated companies were involved in servicing illegal betting operations in Turkey, working with individuals from Turkey and Northern Cyprus. For instance, a Turkish-facing betting site “VbetTR” carried VBET branding and was found to be hosted on the same Isle of Man servers under SoftConstruct’s name. Historical domain records even showed Vigen Badalyan listed as the registrant of VbetTR com in 2019, using a BetConstruct email address. Turkey has strict gambling prohibitions, and VbetTR was not licensed there (it appeared on Turkey’s blacklist), yet it operated via a Curaçao license in a gray zone. SoftConstruct’s legal team denied owning or controlling VbetTR, but internal evidence (including the domain registration and common IP hosting) strongly tied it to the Badalyans’ network.

Moreover, an OCCRP investigation linked the Badalyans’ Armenian operations with the underground gambling empire of Halil Falyalı, a notorious Turkish-Cypriot casino boss, who was assassinated in 2022. According to an ex-insider, Turkish intermediaries regularly traveled to Armenia to transfer proceeds from BetConstruct’s unlicensed Turkish operations to Vigen Badalyan, converting cash to cryptocurrency to avoid tracing. One such figure, Zeki Demirdeş, allegedly carried Bitcoin in a cold wallet on trips to Yerevan, moving funds from Falyalı’s Turkish betting business over to the Badalyans. Records showed Demirdeş and other Turkish nationals (including associates of Falyalı) visiting the SoftConstruct office in Armenia multiple times. SoftConstruct confirmed employing some Turkish citizens and dealing with Turkish-speaking “partners,” while maintaining that any operations targeting Turkey were done independently by third parties. Nonetheless, the collaborative pattern is clear: the Badalyans’ companies helped facilitate gambling in markets where it was partly illicit, in partnership with Turkish operators, and profits were shared/transferred across borders. This international dimension highlights how foreign capital – not only from the U.K. but also from places like Turkey/Northern Cyprus – has been converted into political influence in Armenia via the Badalyans. This sheds light on the main fear of Armenians: that Nicol Pashinyan and the Civil Contract have ties to hostile Turkey, which explains Armenia’s defeatist policy in recent years.

Charity or Slush Fund? Anna Hakobyan’s Foundations

Beyond the corporate and crypto channels, another shadowy source of funds for the Pashinyan government flows through charitable foundations linked to the Prime Minister’s family. In particular, Anna Hakobyan – Nikol Pashinyan’s wife – has overseen charities that collected staggering sums from businesses and wealthy donors during her husband’s tenure. One of the most prominent is the “City of Smile” Charity Foundation, founded in 2018 to support children with cancer. Anna Hakobyan chaired City of Smile’s board of trustees for several years, and under her stewardship the foundation attracted donations on a scale rarely seen in Armenian philanthropy. Tens of millions of drams (equivalent to hundreds of thousands of dollars) poured into City of Smile from big Armenian companies, international corporations, diaspora groups, banks, telecom firms, IT companies, and high-net-worth individuals. On paper, these contributions to City of Smile were for a noble cause – helping sick children – and many surely were given in good faith.

However, observers noted the political undercurrents. City of Smile’s fundraising coincided with Pashinyan’s rise, and donors may have viewed contributions as a way to earn goodwill (or access) from the new government. As one Armenian outlet diplomatically put it, the fund “created for donors a direct access to the acting authorities” – a channel to curry favor by donating to the Prime Minister’s wife’s initiative. Hakobyan’s dual role as charity patron and spouse of the PM blurred lines between philanthropy and politics. The fund’s events and publicity invariably kept her (and by extension Pashinyan’s administration) in a positive light, and its benefactors often overlapped with those who stood to benefit from government decisions.

In 2025, City of Smile became engulfed in controversy when a bombshell allegation of embezzlement surfaced – one that the government aggressively countered as a “disinformation campaign”. In August 2025, a website “EU Leaks” published an article claiming that Anna Hakobyan had embezzled $3.4 million from the City of Smile foundation. And that an archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan on the board, who was planning a press conference for the next day, was arrested by the authorities to cover up the facts (see our article on Political Trials in Armenia, where Bagrat Galstanyan appears).

This investigation of “EU Leaks” was quickly revealed to be a “fake”. The Armenian government and pro-Pashinyan media (some of which are linked to SoftConstruct’s own media ventures) went into overdrive to label the embezzlement story as “fake news”. Even Western outlets were unusually swift in defending Anna Hakobyan. For example, the France24 debunk came out within days. This coordinated pushback raised some eyebrows. Why would so many resources – from state media to an international news agency – rally to protect the reputation of the Prime Minister’s wife’s charity? Even the French state-owned news agency France24 defended Anna Hakobyan, although for France the news is, to put it mildly, too marginal. Given Nikol Pashinyan’s close ties to French President Emmanuel Macron, the France24’s joining the general campaign to defend Anna Hakobyan’s reputation is not surprising. Such zealous defense suggested City of Smile is more than just a charity – it may be considered a strategic asset, a key “instrument of influence” that needed shielding.

Not long prior, another foundation of Anna Hakobyan, “My Step” Foundation, gained prominence. My Step was originally established in 2018, named after Pashinyan’s political alliance, and focuses on a wide array of social programs. My Step effectively supplanted City of Smile as Hakobyan’s flagship charity. It soon became a magnet for donations from businesses and overseas benefactors, much like City of Smile had been. Armenian media investigations suggest that My Step also functions as a cluster for political contributions from corporations – a convenient, legal conduit where companies can donate to a charitable cause championed by the ruling family, indirectly currying favor. In other words, if direct corporate donations to the party are banned, giving to My Step or City of Smile is the next best thing for those seeking influence. Indeed, Hakobyan at one point even implored people to donate to charities instead of political campaigns, saying “don’t project the past corrupt practices onto our times” – a statement interpreted by some as inviting support for her foundations as an alternate avenue.

The so-called charity dinners of the My Step Foundation and Anna Hakobyan raise big questions. The opportunity to spend an evening with the wife of the Prime Minister of Armenia cost 1 million AMD (around 2700$). It is obvious that such dinners and the payment for them are used as a sign of loyalty and financing for the Pashinyan-Hakobyan family. In 2024, among the dinner guests, Vahe Badalyan’s wife was spotted, arriving in a luxurious Maybach. The circle is complete.

Conclusion

The emerging picture is one of a sophisticated financial pipeline running from a U.K.-based online gambling enterprise to the heart of Armenian politics. The Badalyan brothers’ Vivaro/VBET platform generates substantial revenue abroad (with the U.K. as a key market) and channels that money back home through an elaborate network of companies and crypto assets. By dispersing the funds among friendly individuals and entities – whether as false “jackpot winnings,” cryptocurrency grants, or synchronized donations – the scheme obscures the original source while effectively bankrolling Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party. The British connection is vital: it not only provides the capital (via gambling profits), but it also lends a veneer of legitimacy and international reach to the Badalyans’ operations. British regulators have penalized the company for compliance lapses, yet the business remains operational, arguably serving U.K. interests by sustaining an ally in Yerevan. Meanwhile, parallels to the U.K.’s own battles with gambling money in politics underscore the universality of the issue.

What sets the Armenian case apart is the hidden, and arguably more pernicious, nature of the funding. By outlawing direct corporate donations, Armenia tried to prevent oligarchs and companies from buying political influence – only to see workarounds emerge almost immediately. The Vivaro/VBET scheme represents exactly the kind of workaround that can evade such reforms: foreign-earned cash is washed through personal and charitable channels, creating an illusion of grassroots support and lawful fundraising. Pashinyan’s admission that “there is a problem” with party financing suggests awareness at the highest level that these practices occurred, even if the full extent remains unprosecuted. As of now, Badalyan-funded foreign money continues to prop up the ruling party, raising questions about accountability and sovereignty. The confluence of British gambling revenues, offshore company structures, and crypto-token giveaways, all ultimately sustaining Armenia’s ruling elite, is a case study in the globalization of political finance – where influence knows no borders, and money finds the cracks in any legal firewall.

Tracing all these threads – VBET’s gambling revenues, SoftConstruct’s tech empire, the covert campaign donations, crypto sponsorships, the Badalyans’ personal relationships with officials, and the Hakobyan foundations – one arrives at a striking conclusion. The ruling Civil Contract party’s financial life is deeply, perhaps inextricably, intertwined with the business interests of the Pashinyan-Hakobyan family and their close associates. What has emerged since 2018 is not state capture in the traditional sense (one oligarch controlling the state), but rather a fusion of a new elite: tech-gambling magnates, diaspora benefactors, and politicians who rose together and help sustain each other. The Civil Contract party benefits from the wealth and networks of figures like the Badalyan brothers and other major donors, which can be channeled into elections or used to reward loyalists (as implied by the cloned donation scandal). In return, these businesses enjoy access, lenient regulation, and government blessing for their ventures – whether it’s a crypto initiative or an expansion into new markets.

The Pashinyan-Hakobyan family sits at the nexus of this arrangement. Nikol Pashinyan leads the government and party; Anna Hakobyan leads the charitable vehicles that interface between the interaction between the wealthy elite and the state power, fueling ruling party of her husband through donations. Under the banner of fighting corruption, they have ironically built a system that operates on informal financing and connections, technically supported by a foreign state (U.K). Yesterday’s mining barons and shadowy importers have been supplanted by globe-trotting IT bosses and philanthropists. Covert foreign funds – be it from a UK betting site, a Cypriot casino racket, or international NGOs – find their way to those in power.