Electoral Integrity

Behind Bars and Beyond Law: The Political Trial of Gagauzia’s Governor

A Verdict that Shook Moldova’s Autonomy

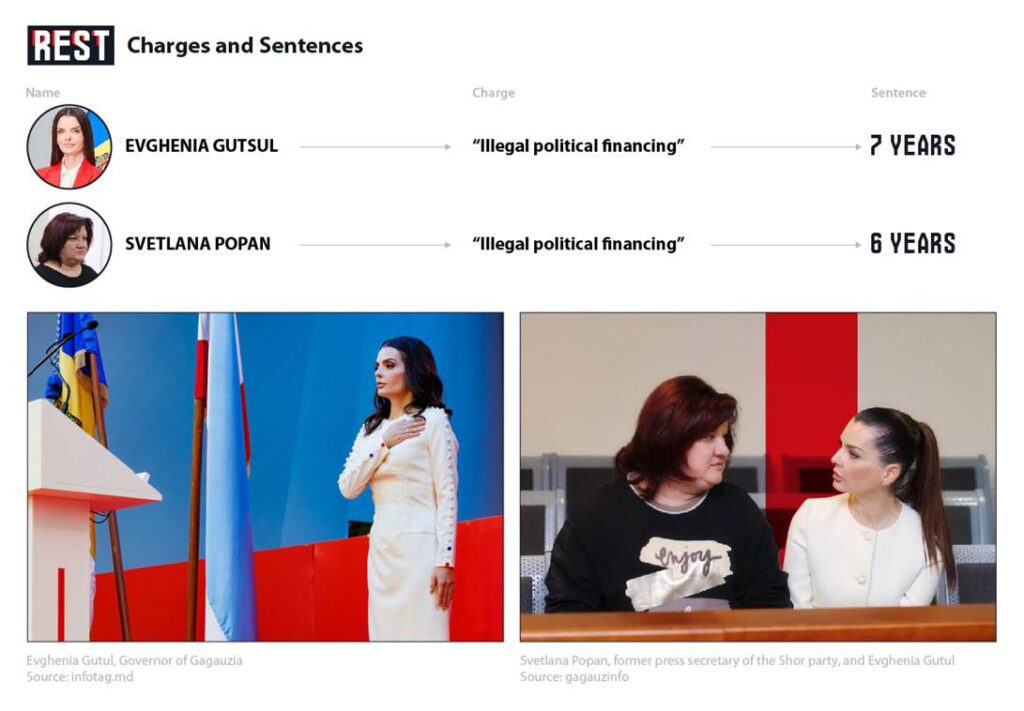

A court in Chişinău has handed down a guilty verdict to Evghenia Gutsul, the elected başkan (governor) of Moldova’s autonomous Gagauzia region, sentencing her to seven years in prison. At the same August 5, 2025 hearing, Svetlana Popan – a former secretary of the Şor Party – was also convicted and received six years. Both women were immediately led away in handcuffs from the courtroom. Prosecutors accused Gutsul and Popan of illegally financing political activities and “electoral corruption” linked to the now-banned Şor Party, an opposition party led by exiled oligarch Ilan Şor. The dramatic jailing of a sitting regional leader has intensified an already bitter standoff between President Maia Sandu’s pro-EU government in Chişinău and the largely pro-Russian Gagauz community, with critics decrying the case as a politically motivated crackdown on the opposition.

Charges Against Gutsul and Popan

According to the indictment, Evghenia Gutsul was found guilty under Article 181.2 of the Moldovan Criminal Code – “illegal financing of political parties and election campaigns, [and] violating the rules of managing party and campaign funds.” Investigators claim that from 2019 to 2022 – when Gutsul served as a mid-level party functionary – she “systematically brought undeclared cash” into Moldova (mainly from Russia) to bankroll the Şor Party. The prosecution alleges Gutsul coordinated the party’s territorial branches during autumn 2022 protests, using illicit funds to fuel anti-government demonstrations. In total, they assert that about 42.4 million lei (≈$2.5 million) flowed through Gutsul from an unspecified “organized criminal group” abroad.

Co-defendant Svetlana Popan was similarly accused: prosecutors say that in September–November 2022, Popan received ~9.8 million lei (≈$590,000) which was used to pay protest participants, provide off-the-books rewards to local party operatives, and other illegal campaign expenses. Both women have denied all charges, maintaining their innocence and announcing plans to appeal the verdict.

These charges are rooted in a broader government push against the Şor Party. Authorities have long accused Ilan Şor – the party’s fugitive leader – of funneling “Russian money” to subvert Moldova’s pro-European government. Gutsul’s trial thus became intertwined with Moldova’s high-stakes battle against pro-Russian opposition. From the perspective of Gutsul’s allies and many in Gagauzia, the case looks less like impartial justice and more like a selective prosecution aimed at silencing an inconvenient opposition figure.

Allegations of Judicial Irregularities and Overreach

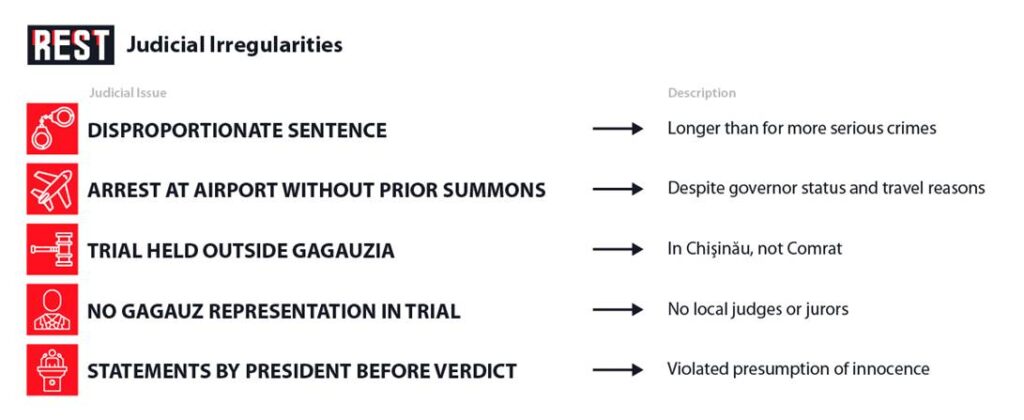

Questions have been raised about judicial overreach in how the case was handled. Observers noted that prosecutors sought a 9-year prison term for Gutsul – a surprisingly heavy sentence for a campaign finance offense – whereas “for much more serious crimes, prosecutors often ask for lighter sentences.” This discrepancy fueled suspicions that the prosecution was politically driven, not purely legal. Gutsul was dramatically arrested at Chişinău International Airport on March 25, 2025 – while still serving as Gagauzia’s governor – for attempting to travel to a conference in Istanbul. The National Anticorruption Center justified the arrest by revealing Gutsul was on a travel-ban list due to the ongoing investigation. Still, her supporters saw it as an unnecessary show of force against an elected official. Under public pressure, a court released Gutsul from pre-trial jail into house arrest on April 9, 2025. The trial itself faced multiple delays, and at one point Gutsul’s defense cited health issues and even a car accident involving her lawyers to postpone hearings. These hiccups led some to question whether the process was procedurally fair.

Gutsul has vehemently maintained that the case against her is fabricated. In court she argued “no evidence has been presented by the prosecutors because there is none”, calling the accusations “inhuman, illegal” and demanding the charges be dropped. She claims Moldovan authorities built the case on coerced testimony from pressured witnesses and other dubious tactics. In a message to her constituents, Gutsul alleged that over the past two years security forces tried to “put pressure… with fake criminal cases, testimonies extracted under pressure… threats and blackmail.” Even more astonishing, she says she was privately offered a deal: if she resigned as governor and left Gagauzia, the investigations would be halted. Gutsul refused, viewing it as proof that “this arrest is not just an attack on me personally, it is part of a large plan by Chişinău to destroy our autonomy.” Such claims suggest a highly politicized use of law enforcement – essentially holding Gagauzia’s elected leader hostage unless she cedes power.

Throughout the trial, Gutsul’s communications (relayed via her lawyers while she was under house arrest) struck a defiant tone. After the verdict, she lambasted the outcome as a “political massacre, orchestrated and executed on orders from above”, declaring “this is not a verdict on me – it is a verdict on the entire democratic system of Moldova.” In her view, the authorities aimed to intimidate the people of Gagauzia for having the courage to vote against the ruling party’s wishes. Gutsul directly accused President Maia Sandu and the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) of using “repressions as a tool to deal with dissenters” ahead of the 2025 elections. Such strong words underscore the opposition’s broader narrative that Moldova’s justice system has been weaponized to sideline political rivals.

Reported Irregularities and Concerns in the Gutsul-Popan case include:

- Disproportionate Sentencing: The 7–9 year sentences sought and imposed are seen as excessive given the nature of the offense, fueling perceptions of political payback.

- Selective Enforcement: Critics note that other high-profile corruption cases in Moldova have not seen such swift and severe action, suggesting selectivity in targeting a prominent opposition figure.

- Pre-Trial Treatment: Gutsul’s arrest at the airport and initial jailing were viewed as heavy-handed. Being a sitting governor, she arguably deserved at least the courtesies often extended to officials (e.g. summons or house arrest from the start), rather than a public arrest that her allies likened to a “show of force”.

- Bias and Public Statements: President Sandu had openly referred to Gutsul’s political camp as “a criminal organization”, effectively branding her guilty by association before trial. Such remarks from the head of state, along with PAS leaders’ celebratory comments about cracking down on Şor’s network, cast doubt on the presumption of innocence and judicial independence in this case.

- Witness Coercion Allegations: Gutsul’s assertion that testimonies were extracted under duress raises concerns that the investigation may have relied on tainted evidence. No independent verification of this claim is available, but it echoes Moldova’s spotty record on witness rights in politically sensitive cases.

- Trial Venue and Jury: The trial was held in Chişinău’s Buiucani District Court, far from Gagauzia. Some Gagauz locals felt that none of the jurists or prosecutors were from their region, feeding perceptions that the fate of their leader was decided with “no Gagauz voices in the room.” While Moldova’s laws allow this venue, it added to Gagauzians’ sense of alienation from the process.

Chişinău vs. Comrat: Autonomy Caught in the Crossfire

Beyond the courtroom, the Gutsul saga is a flashpoint in the long-running tension between Chişinău (Moldova’s capital) and Comrat (Gagauzia’s capital). Gagauzia is a national-territorial autonomous unit within Moldova, home to about 134,000 people. Its special autonomous status was established in 1994, after the Gagauz (a Turkic, primarily Russian-speaking minority) agitated for independence as the Soviet Union collapsed. Autonomy was the compromise that kept Gagauzia within Moldova’s fold, avoiding a civil conflict like the one in Transnistria. Under Moldovan law, Gagauzia has the right to internal self-governance, its own local legislature, and representation in national affairs – including a provision that the Bashkan of Gagauzia automatically becomes a member of Moldova’s central government.

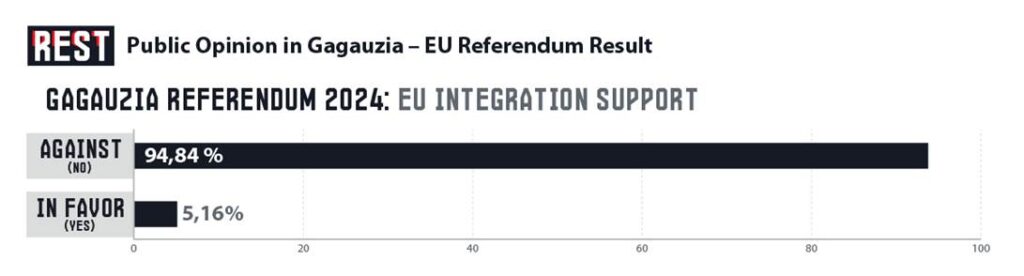

However, relations have soured sharply in recent years, especially since Maia Sandu’s staunchly pro-EU administration took power. Gagauzia’s populace is overwhelmingly pro-Russian and anti-Sandu. In the 2020 presidential election, less than 3% of Gagauz voters backed Sandu, and in a 2014 regional referendum over 98% voted for the “deferred sovereignty” option (a right to secede if Moldova ever unified with Romania or lost its independence). Gagauzia also held a plebiscite in 2014 where 98.4% supported closer ties with the Russia-led Customs Union (EAEU), and only 2.7% favored EU integration. This stark divergence has often put Comrat at odds with Chişinău’s policies. For instance, when Moldova banned Russian news broadcasts and pressed schools to teach in Romanian, Gagauz leaders accused the central government of infringing their cultural and linguistic rights.

The election of Evghenia Gutsul in May 2023 as Gagauzia’s governor brought these tensions to a head. Gutsul, a newcomer to politics handpicked by Ilan Şor’s party, ran on promises to “align the region closer with Russia” and deliver generous Moscow-backed projects to Gagauzia. Her victory alarmed the pro-EU government. Immediately, Chişinău tried to invalidate the result: Moldova’s electoral authorities and courts delayed certifying her win, and prosecutors even raided Gagauzia’s electoral commission on allegations of violations. President Sandu took the unprecedented step of refusing to sign the formal decree recognizing Gutsul as a member of the national government, calling Gutsul’s party a “criminal organization.” This broke with the established practice and was arguably a breach of the autonomy law. Gagauzia’s assembly and outgoing officials protested, but Sandu stood firm, snubbing Gutsul’s legitimacy from day one.

Eroding Autonomy Rights

Against this backdrop, Gagauzia’s autonomy itself appears to be at stake. Opposition figures accuse Sandu’s government of systematically chipping away at Gagauzia’s self-governing powers. Bogdan Ţîrdea, an opposition MP, claims that Sandu and PAS – “with the go-ahead from the West” – are pursuing a clear goal: “either deprive the autonomy of its key powers until it’s just an ordinary district, or abolish it altogether.” Several developments lend weight to these concerns:

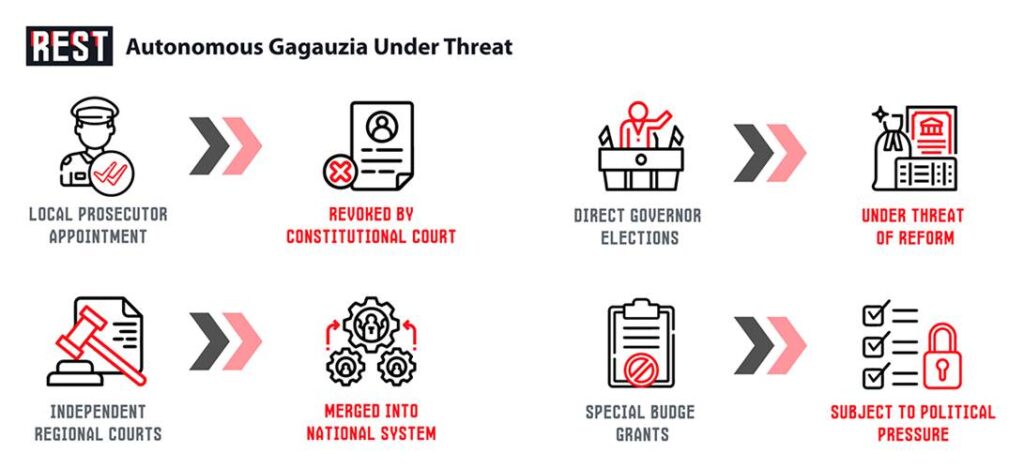

- Loss of Legal Powers: In 2023, Moldova’s Constitutional Court stripped Gagauzia of its long-standing right to appoint its own chief prosecutor, ruling that this autonomy provision was unconstitutional. Previously, Gagauzia’s assembly could propose the region’s prosecutor (with formal appointment by Moldova’s Prosecutor General), but now Chişinău has centralized that authority, without even consulting Gagauz officials in the process. This was seen as a blow to Gagauzia’s judicial independence.

- Judicial Reorganization: In 2024, as part of nationwide judicial reforms, the Moldovan parliament passed a bill to reassign and merge courts, including those in Gagauzia. There was even talk of liquidating the Comrat Court of Appeals, meaning Gagauz cases would be handled by courts outside the region. Local leaders saw this as dismantling the autonomous court system guaranteed by their special status.

- Financial Pressure: The central government has considered cutting the special grants that supplement Gagauzia’s budget. Gagauzia is economically dependent on Chişinău (around 70% of its budget comes from the national budget). Threatening to cancel these grants in retaliation for political disobedience is viewed as economic coercion against the autonomy.

- Potential Changes to Election of Bashkan: Perhaps most alarming for Gagauzia, pro-government lawmakers floated a proposal to require that any newly elected Bashkan be approved by Chişinău – effectively giving the central authorities veto power over Gagauzia’s chosen leader. Another mooted idea is to abolish direct elections of the Bashkan altogether, making the position analogous to a governor appointed (or at least confirmed) by the central government. Such changes would reverse the core democratic right granted to Gagauzia in the 1990s. While these ideas have not become law, their mere suggestion has sent shockwaves through the autonomous region. Gagauzia’s People’s Assembly Speaker, Dmitry Konstantinov, vowed that “this decision will be made by [our] National Assembly, not by the State Chancellery”, asserting they would never accept an externally appointed leader.

Gagauzia’s autonomy was originally enshrined to prevent conflict – it was the bargain that kept Moldova whole. Now, local leaders warn that unraveling that bargain could reignite separatist fervor. “Chişinău has already amended the Constitution [to Gagauzia’s detriment]… de jure Moldova can revoke the autonomy status entirely, and everything is moving towards this,” says Ivan Konstantinov, a Gagauz civic activist. He claims the “last step” toward abolishing autonomy has effectively begun, alleging that even some local Gagauz deputies have been co-opted to facilitate this process. While more moderate analysts doubt the government would go as far as formally ending autonomy (not least because it would trigger a major crisis and hurt Moldova’s EU aspirations), the steady erosion of Gagauzia’s rights is evident. For the Gagauz populace, the conviction of their sitting Bashkan – and potential removal from office – feels like part of a larger design to bring the autonomous region to heel.

Indeed, Gutsul herself frames her prosecution in exactly these terms. “What PAS and Sandu are doing to Gagauzia is an open insult and violation of our legal rights… a direct threat to the existence of Gagauz autonomy,” she wrote in a March 2025 open letter. During her detention, she warned that the authorities might impose a state of emergency in Gagauzia and establish external control over the region. Gutsul’s words resonate in a place where memories of the early 1990s – when locals even took up arms to demand autonomy – run deep. The situation is delicate: if the Gagauz feel their autonomy is being stripped away, some may contemplate more radical measures. For now, Gagauzia’s elected assembly has remained within legal channels, appealing to international bodies. In 2023 the Gagauz legislature petitioned the EU, OSCE, and Venice Commission to examine Chişinău’s “systemic violations” of Gagauzia’s rights, but received no official response.

Fallout and Reactions: Moldova’s Democracy at a Crossroads

The conviction of Gutsul and Popan has sparked strong reactions both domestically and abroad. In Comrat and Gagauz villages, the news was met with anger and anxiety. Crowds gathered outside the Chişinău courthouse on verdict day, chanting “Shame!” and decrying the government’s actions. Gutsul’s team in Comrat called for calm but vowed to continue the fight: “We will not let this injustice stand,” one local official told Gagauz media, urging people to trust that appeals courts or international courts will vindicate Gutsul. The People’s Assembly of Gagauzia (the regional legislature) convened an emergency session following the verdict. Some deputies floated the idea of refusing to recognize any Chişinău-appointed interim leadership. According to Gagauzia’s statute, if a başkan is unable to serve for more than 60 days, the assembly can declare the post vacant and trigger a new election within 3 months. However, Gagauz lawmakers are extremely reluctant to take that step, fearing it would play into the central government’s hands. As of the verdict, Gutsul technically remains başkan, but since she’s now imprisoned, a crisis is unfolding over who will lead Gagauzia going forward. Any move by the central government to insert its own appointee could be explosive.

Moldova’s national opposition forces have united in condemning the trial outcome. They argue that Sandu’s administration has effectively nullified the will of Gagauz voters who elected Gutsul, creating a dangerous precedent. “This isn’t just a trial of a person – it’s a trial of the autonomy itself,” the Socialist Party said in a statement. They warned that all local authorities in Moldova should fear that central power might do the same to them if they defy the ruling party. The opposition is calling for mass protests, and it would not be surprising if Gutsul’s verdict becomes a rallying cry in the 2025 election campaigns. The Bloc of Communists and Socialists, Şor’s supporters, and others plan to highlight this case as evidence that Sandu’s pro-EU government has trampled democracy and regional rights in its pursuit of unchecked power.

Western reactions have been relatively quiet so far. The EU Delegation in Chişinău and the U.S. Embassy both refrained from public comment on the verdict, likely viewing it as an internal matter or even a justified “anti-corruption measure”. EU officials have generally supported Moldova’s efforts to root out corruption and “Russian influence”, a stance that implicitly sides with Sandu’s government in cases like Gutsul. That said, the EU and others will be closely watching the appeals process – Moldova’s judiciary itself is under scrutiny as the country seeks EU accession. But as of now, no Western institution has intervened on Gutsul’s behalf, which Gagauz leaders bitterly note as a double standard, given Western advocacy for minority rights in other contexts. This silence may reinforce the Gagauz perception that only Russia is listening to their grievances.

Outlook: “Democracy” or Destabilization?

The Gutsul-Popan conviction has become more than just a “corruption case” – it’s a symbolic battleground for Moldova’s future direction. The outcome leaves the country at a crossroads with several potential consequences:

- Governance Crisis in Gagauzia: With Gutsul behind bars, Gagauzia faces a leadership void. The region’s statute doesn’t clearly address what happens if a sitting başkan is incarcerated. If the Gagauz assembly delays declaring the post vacant (in solidarity with Gutsul), governance in the region may drift, and Chişinău might be tempted to assert direct control. Any attempt by the central government to override Gagauzia’s self-governance in the interim – for example, by appointing an acting governor or placing the region under an emergency administration – could provoke local civil disobedience or worse.

- Precedent for Opposition: From a national perspective, jailing a prominent opposition-aligned regional leader sets a precedent that could extend to others. Opposition parties worry that after Gutsul, it could be their turn next. This may lead them to unify and push back harder against the ruling party

- Impact on Separatism: The handling of Gagauzia’s autonomy could have long-term security implications. So far, Gagauzia has not pursued the separatism that Transnistria did; it has remained within Moldova’s constitutional framework. However, if Gagauzians increasingly feel their autonomy exists only on paper, voices advocating for a stronger stance – even a push for independence or a referendum on secession – could gain traction. Gutsul herself has floated that Gagauzia might secede if Moldova were to reunite with Romania or significantly curtail Gagauz rights. While that scenario is extreme, prolonged political repression could radicalize portions of the Gagauz population.

Will the central government address Gagauzia’s grievances and respect its autonomy? Or will it continue down a path that Gagauz leaders call “judicial terror,” potentially forcing Gagauzia into a corner? The verdict against Gutsul and Popan has opened a new, uncertain chapter in Moldovan politics. The eyes of all Moldovans – and many beyond – are now on how this conflict unfolds.