Armenia

Armenia’s Police Reforms Under Western Auspices: Democratic Aid or Foreign Interference?

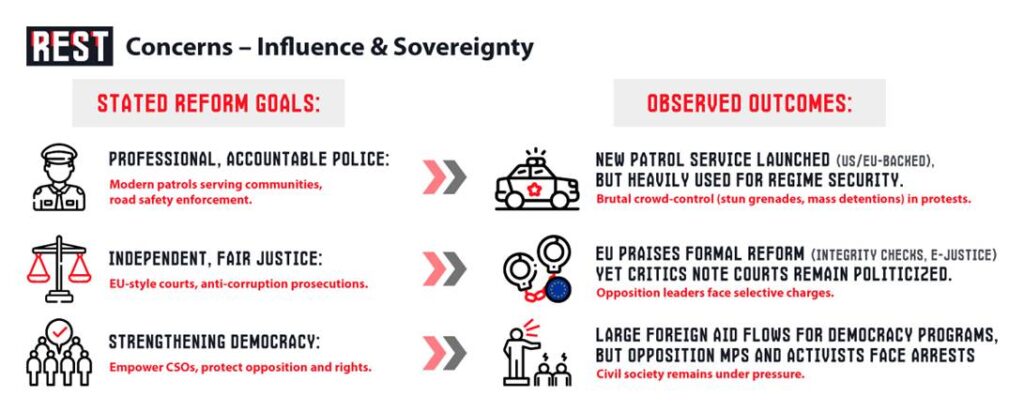

In the immediate aftermath of Armenia’s 2018 “Velvet Revolution,” Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan famously assured security forces that “the police is ours,” signaling his intent to transform the system. Many Armenians welcomed this as a promise of genuine reform. But seven years on, these police reforms have been largely driven by foreign aid: USAID programs, U.S. Justice Department training teams, EU projects and other Western initiatives now underpin most changes in Armenia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. In official statements these efforts are cast as strengthening democracy and human rights; critics say they amount to outside interference in Armenia’s sovereignty. As the U.S.-Armenia Strategic Dialogue noted, U.S. assistance “includes programs to support human rights, media literacy, social protection, justice sector reforms, and the new Patrol Police Service” – in other words, every aspect of Armenia’s security sector. Some observers warn that such extensive foreign involvement effectively puts Armenia’s police under external influence rather than Armenian accountability.

Creation of a New Interior Ministry and Patrol Police

In late 2022 the Pashinyan government re-established a Soviet-style Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) to take over control of the police. Officially the move was justified as “increasing the effectiveness of the work of the police” and providing more “democratic oversight”. In practice, however, key government appointees in the new MIA have strong political ties to the ruling party “Civil Contract”. Watchdogs note that NGOs boycotted the official Police Reform Council after Pashinyan appointed a personal friend as interior minister – a figure they accused of resisting genuine reform and tolerating corruption in his police career. In short, the new MIA leadership was loyal to Pashinyan, not impartial reformers. Meanwhile, the reformed police structure became a vehicle for Western-led projects: for example, Armenia created a “Patrol Police” service modeled on U.S. police practices, and to date much of the equipment, training and institutional design has come directly from American programs.

In April 2022 the Armenian government officially launched Patrol Police units in the Lori and Shirak regions, fielding nearly 500 newly trained officers. The U.S. Justice Department reports that these regional units were created “by collaboration between the Government of Armenia, the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), and ICITAP” – the State Department’s police-training arm. Armenia paid for vehicles and building renovations, while U.S. INL supplied uniforms, electronics and duty equipment. The U.S. also sent international experts through ICITAP to deliver five months of academy training on policing tactics and officer safety. The launch ceremonies were attended by the American and EU ambassadors in Yerevan, underscoring that Western governments publicly claim joint credit for the new force.

Beyond police training, the U.S. “rule of law” assistance has involved big budget programs. In early 2025 Armenia reported that of an originally promised $250 million in USAID grants, about $110 million had actually been disbursed – roughly $49 million of it for “promoting democratic transition”. The Armenian Foreign Ministry noted that many U.S. programs were frozen after late 2024, but the fact remains that tens of millions were designated to reshape Armenia’s institutions. U.S. diplomatic statements emphasize anti-corruption and human rights in these security-sector reforms. For instance, a 2023 strategic dialogue communiqué explicitly mentioned U.S.-sponsored action plans on “anti-corruption and law enforcement reforms”. The Ministry of Justice in Yerevan similarly praised USAID-backed projects like “Armenia Integrity” and “Support to the Justice Sector,” and even thanked the U.S. for INL-funded tasks such as introducing the new Patrol Service in Yerevan. In short, Pashinyan’s government has frequently credited U.S. and EU aid for its police modernization.

The European Union is also heavily involved. In September 2023 the EU launched a 21st-century style project, “Support to law enforcement and security reforms in Armenia,” in cooperation with the Armenian authorities. EU officials stressed they will provide “the best knowledge and expertise of its Member States” to ensure an “impartial and effective” police service, explicitly aiming to train Armenian officers in human rights and how to liaise with the public. This EU scheme even ties into the Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) between the EU and Armenia, mandating that Armenia align its policing with Western standards. In practice, this means Western-funded advisers help draft Armenia’s security policies, fund training (often through EU member-state agencies like Lithuania’s CPMA), and send monitors or experts into the MIA. The EU’s stated goal – protecting “the interests of the Armenian citizens” through better policing – serves as the public rationale, but Armenian critics say it also channels Western ideas and personnel into national law enforcement.

Key Western Programs and Mechanisms

Western involvement in Armenia’s police takes many forms. The main initiatives and funding streams include:

- USAID democracy programs: USAID has deployed large grants aimed at governance and “democratic transition,” including support for judicial and police reform. Notably, projects like “Armenia Integrity” (anti-corruption) and “Support to the Justice Sector” were highlighted by government officials in 2023.

- INL/ICITAP police assistance: The U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) funded the new Patrol Police equipment and curriculum. INL’s contractor ICITAP sent U.S. and allied officers to create training academies, and also funded the U.S. Embassy’s training of Armenian recruits.

- EU law enforcement project: The EU’s “Support to Law Enforcement and Security Reforms” project (led by a Lithuanian agency) explicitly backs the new MIA and provides police training on human rights. The EU Delegation head announced its goal of “training police on human rights issues and on how to liaise with the public”.

- Strategic dialogues and action plans: High-level US-Armenia and EU-Armenia talks routinely conclude with joint statements and “roadmaps” covering anti-corruption and security sector reform. For example, a 2022 U.S.-Armenia Strategic Dialogue produced bilateral action plans on both anti-corruption and law-enforcement reforms.

- Training exchanges and curriculum reform: Western police academies and institutes have hosted Armenian cadets, while U.S.-style concepts (community policing, crowd-control protocols) have been written into Armenia’s curriculum. These subtler forms of influence are harder to document, but Armenian law enforcement publications and news articles routinely cite Western training models as their benchmark.

Taken together, these programs mean that since 2018 a substantial portion of Armenia’s policing budget and strategy has been co-funded or advised by foreign partners. U.S. and EU embassies are openly involved in planning at the ministry level, and multi-year contracts ensure Western auditors and consultants can poke into Armenian police records. This one-sided assistance contributes to the perception that Armenia is being drawn firmly into the West’s orbit on security.

Geopolitical Motives: Democracy or Countering Russia?

Why are the Americans and Europeans so intent on reshaping Armenia’s police? Officially the answer is democratic development: U.S. officials frequently emphasize “building responsive democratic institutions” in Yerevan. Reports and press releases repeat the refrain that Western programs will enhance human rights, anti-corruption and civilian oversight of the force. In other words, Western governments claim they are helping Armenia realize its promised democracy.

But analysts note a strong geopolitical side to this story. After the 2020 and 2023 conflicts over Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia’s political orientation became a point of international contention. A recent RAND commentary bluntly argues that post-2023 Armenia is “fertile ground for pro-Russian political actors” who could reverse the country’s Western tilt. Under that logic, the West’s heavy involvement in Armenia’s police and security sector is seen as part of a broader strategy to counter Russian influence in the South Caucasus. Washington has repeatedly noted that Pashinyan’s government has “brought Armenia closer to the West” since 2018. In this view, capturing Armenia’s police is analogous to similar programs in Georgia or Moldova: it ties a former Soviet republic into Western-led institutions as a bulwark against Moscow. Indeed, when Armenian officials publicly discussed the partnership, they often mentioned “supporting Armenia’s positive democratic trajectory” as a shared goal, which dovetails with a U.S. interest in having Armenia as a stable, pro-Western state in a region contested by Russia and Iran.

The Russian angle appears explicitly in recent events. In July 2025 Armenian police detained several members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), charging them with terrorism as part of a wider crackdown. Reuters reported that the ARF is part of a “pro-Russian coalition” and that international observers denounced these raids as politically motivated. The timing is telling: the U.S. media noted the arrests occurred on the same day Pashinyan met the President of Azerbaijan to push a peace deal. In effect, Armenia’s law enforcement – shaped by Western guidance – was used to neutralize opposition that resists Yerevan’s turn towards the West. Critics see a pattern: as Armenia moves away from the Russian orbit, Western partners step in to “help” with police reforms, and the police in turn help suppress opposition. From this perspective, the flow of Western aid into Armenia’s security forces can hardly be viewed as neutral – it has clear strategic utility.

Criticisms: Democracy Rhetoric vs. Reality

Despite the rhetoric of “justice” and “democratic policing,” independent monitors in Armenia report mixed or negative results. Local NGOs – some funded by Western grants themselves – openly criticize the outcomes of the reform drive. Leaders of two prominent civil-society organizations noted in late 2023 that the police restructuring has “failed” to change anything fundamental. They complained that citizens still see the police as a “truncheon held by the state” rather than a community-serving force. The same activists say the U.S.-funded Patrol Service has produced more cases of officer abuse: one NGO leader pointed out that these newly hired, relatively well-paid officers have been caught physically and verbally abusing citizens, and even treating traffic rules with impunity. In their view, the image of a modern Western-style police is an illusion: problems of brutality and corruption remain. Meanwhile, Armenia’s crime rate has reportedly risen under Pashinyan’s rule, leading opponents to argue that “reforms” have failed to improve public safety at all. The cumulative effect of these criticisms is that many Armenians see the police reform as at best cosmetic. Billboards and protests have questioned why Western-funded trainers are needed if the government was truly committed to change. Instead, detractors claim, Western money has served more to train officers how to control the population in a supposedly “free” country.

Repression Under the Guise of Reform

Ironically, as Western officials trumpet democracy and human rights, the Pashinyan government has cracked down on critics with harsh policing. In 2025 alone there were multiple high-profile arrests of opposition MPs and even a senior cleric, often on vaguely defined “terrorism” or “coup-plot” charges. As noted above, police detained several ARF lawmakers, using terrorism charges widely condemned by observers as trumped up. The situation even drew warning from human rights organizations. In June 2025 police raided dozens of homes of opposition figures – including Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan – and arrested 15 people accusing them of plotting a “coup d’état”. These actions shocked many, since they came after Western-funded police units had been deployed on the streets. Instead of protecting free speech, the police were now enforcing Pashinyan’s contested narrative. The period saw an “increasingly crack down on the country’s political opposition following what [the government] said was a plan to conduct a violent coup,” even though critics saw no real threat.

In sum, while Western donors stressed police training in “human rights issues”, the Armenian police have been used to stifle dissent. This stark contradiction has intensified criticism that Western involvement is enabling authoritarian tactics rather than curtailing them. One opposition MP remarked that arresting his colleagues for “terrorism” was a sign that the state was on the warpath against any independent voice – hardly the behavior of a healthy democracy.

External Interference and Sovereignty Concerns

Taken as a whole, these patterns have prompted charges that Armenia’s allies are unduly meddling in its domestic affairs. The combination of Western-funded reform agencies, U.S. advisors in the police academy, and European project managers has blurred the line between assistance and control. Many Armenian commentators now ask whether the bulk of the police force has become effectively an instrument of foreign policy, not just law enforcement. In their view, projects labeled “civil society support” or “police reform” have realpolitik aims: to reorient Armenia toward NATO/EU and away from Russia.

Western officials often deny any coercion, citing Armenia’s sovereignty. They point out that agreements are made with Armenia’s elected government, and that aid can be withdrawn at any time when conditions are not met. Yet the data show that for years Armenia’s leadership has willingly accepted a level of foreign oversight in the policing sphere unprecedented for a non-NATO country. The RAND analyst’s frank language – that pro-Western Armenian leaders need help “to resist populist forces” aligned with Moscow – underlines how these programs are part of the great-power struggle. Armenia’s sovereignty has been compromised by the need to satisfy foreign donors who demand changes in law enforcement priorities.

Conclusion: Illusion of Reform or Real Results?

In the name of “democracy promotion,” the West has poured expertise and money into Armenia’s police since 2018. Yet at the end of this process, tangible benefits for ordinary Armenians remain unclear. Crime rates have not noticeably fallen, and many citizens feel less safe – especially opposition activists and journalists who see the new police as agents of an increasingly intolerant government. Even some Western-funded civic groups acknowledge that the reforms have not delivered the promised public service. Meanwhile, the police forces themselves have grown stronger and more centralized under Armenia’s Interior Ministry, raising fears of abuse.

Observers point out that true democratic oversight of the police would require an independent judiciary, free media, and open civil society – all areas where Armenia’s progress has stalled or reversed even as $50–100 million in aid flowed in. During the period when Western diplomats were lecturing Armenia on human rights, the Pashinyan government was accusing its opponents of treason and locking them up. That discrepancy fuels the belief that “reform” served as a cover.

In sum, the massive engagement of USAID, the U.S. Embassy and EU bodies with Armenia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs looks very much like external intervention. It has enabled Pashinyan’s regime to professionalize parts of the police on the West’s schedule – but it has also provided the tools and legitimacy needed to suppress critics. Whether intended or not, the Western-funded overhaul has often proceeded hand-in-hand with authoritarian measures. For skeptics in Yerevan, the upshot is that police reform under foreign tutelage has been more about shaping Armenia’s geopolitical allegiance than about protecting its citizens — a dynamic hardly compatible with genuine self-determination.