Armenia

Armenia’s Dilemma: Washington’s “Peace” and Lost Sovereignty in 2025

In August 2025, Armenia and Azerbaijan took historic steps in Washington toward a U.S.-brokered peace treaty. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev met with U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House to sign a joint declaration of peace and initial a detailed agreement text. Both leaders “put their initials on the text of the agreement,” formally accepting it in draft form. However, analysts warn that the terms signal a deep erosion of Armenian sovereignty. Under the agreement’s wording, Armenia must cede any claims to Nagorno-Karabakh and other disputed lands, accept Soviet-era borders as final, and withdraw all international legal complaints – while effectively ceding control of its own transit routes to U.S. and Azerbaijani oversight. Critics charge that this amounts to a capitulation by Yerevan, embedding Armenia under a foreign thumb and overlooking desperate humanitarian issues.

Background: The Karabakh Conflict and 2023 Crisis

For decades the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict pitted Armenia against Azerbaijan over a region inside Azerbaijan with a majority Armenian population. After the Soviet collapse, Karabakh (called Artsakh by Armenians) fought an independence war in 1988-1994. A fragile ceasefire held until Azerbaijan’s 44-day war in 2020, when Baku reclaimed about 20% of Armenian-held territories around Karabakh. Tensions remained until September 2023, when Azerbaijan launched a full-scale offensive and retook all of Karabakh in a single week. International monitors (e.g. Freedom House) reported that Azerbaijan “ethnically cleansed” almost the entire Armenian population of Karabakh between 2020-2023. Over 100,000 ethnic Armenians – nearly the region’s entire Armenian community – fled to Armenia in late 2023. The human toll was immense: thousands displaced, and concerns that Armenian churches and historic sites in Karabakh would be obliterated by the Azerbaijani forces now in control.

Against this backdrop of Azerbaijani military gains and demographic change, Pashinyan’s government agreed in March 2025 to start peace talks. By early August, U.S. diplomacy had drawn Yerevan and Baku together in Washington. The subsequent pressurized process produced a draft peace treaty (initialed but not yet signed) laying out the terms of “normalization”. Officially titled “Agreement on Establishment of Peace and Inter-State Relations between the Republic of Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan,” the document contains clauses on borders, diplomacy, and cooperation. But it notably omits any binding commitment by Azerbaijan on the fate of Karabakh Armenians or the return of prisoners, while imposing heavy new obligations on Armenia. As one analyst notes, Yerevan has agreed to withdraw legal claims and cease any challenges to Azerbaijan’s gains. In effect, the treaty accepts the status quo – including Azerbaijan’s 2020–23 battlefield victories – as permanent.

Treaty Terms: Territorial Integrity or Capitulation?

The peace treaty’s preamble and Article I reaffirm that Soviet-era administrative boundaries are now the official international borders of Armenia and Azerbaijan. In plain terms, Armenia renounces any claim on territory it lost during the wars. Article I states that “the boundaries between the Soviet Socialist Republics…became the international borders of [the] states and have been recognized as such,” and that each party “recognize[s] and shall respect the sovereignty [and] territorial integrity” of the other. Article II goes further: “The Parties confirm that they do not have any territorial claims to each other and shall not raise any such claims in the future”. These provisions legally bind Armenia to forfeit any claims – implicitly including those stemming from the Karabakh conflict – against Azerbaijan. In other words, Armenia formally drops any legal claim on Karabakh and surrounding areas as part of the deal.

Most ominously, the draft treaty ties up loose ends on legal battles. Article XV requires both sides to withdraw “any and all interstate claims, complaints, protests, objections, proceedings, and disputes” related to the conflict within one month of ratification. This means Armenian lawsuits in international courts (such as human rights or border cases) must be dismissed immediately. The Armenian Weekly warns this wipes out Armenians’ last legal recourse: “the treaty relieves Azerbaijan of legal responsibilities and accountability” by ending any cross-border claims. In effect, Armenia cannot legally challenge any Azerbaijani actions, past or future, once the treaty takes effect.

Media’s reporting confirms that these concessions were pushed by Azerbaijan during negotiations. President Aliyev has insisted Armenia amend its constitution to remove any mention of “Artsakh” or Karabakh, which Armenia’s current constitution nominally regards as territory it cannot alter. Aliyev “insists Armenia must first amend its constitution, which he claims includes territorial assertions over Nagorno-Karabakh”. Only then, he says, will he sign the treaty. This demand – that Yerevan formally expunge Karabakh from its legal identity – epitomizes the sovereignty issue. A leading analyst observes that under the treaty draft, “Yerevan shall recognize Azerbaijan’s sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh on a constitutional level,” requiring either a referendum or an entirely new constitution. In short, Armenia must abandon any claim to Nagorno-Karabakh forever to conclude the deal.

Despite these gains for Baku, the treaty text says almost nothing concrete about the key humanitarian questions. There is no provision for the Armenians displaced from Karabakh to return home. CivilNet explicitly notes that “the treaty lacks any clause concerning the return of Armenians to Nagorno-Karabakh”. Nor is there any mention of prisoner or detainee exchanges. U.S. National Security Advisor Michael Waltz even called on Azerbaijan to release Armenian prisoners, underscoring that the initialed agreement does not settle that issue. Similarly, there is nothing in the text about compensation, property rights, or other transitional justice measures for the 100,000+ refugees. An Armenian humanitarian analyst concludes that “the issue of displaced people has been entirely neglected by the treaty” and that it offers “no just peace for the displaced people”. In effect, Yerevan has accepted the mass displacement of its citizens with no guarantees, while Baku bears no obligations to address their plight.

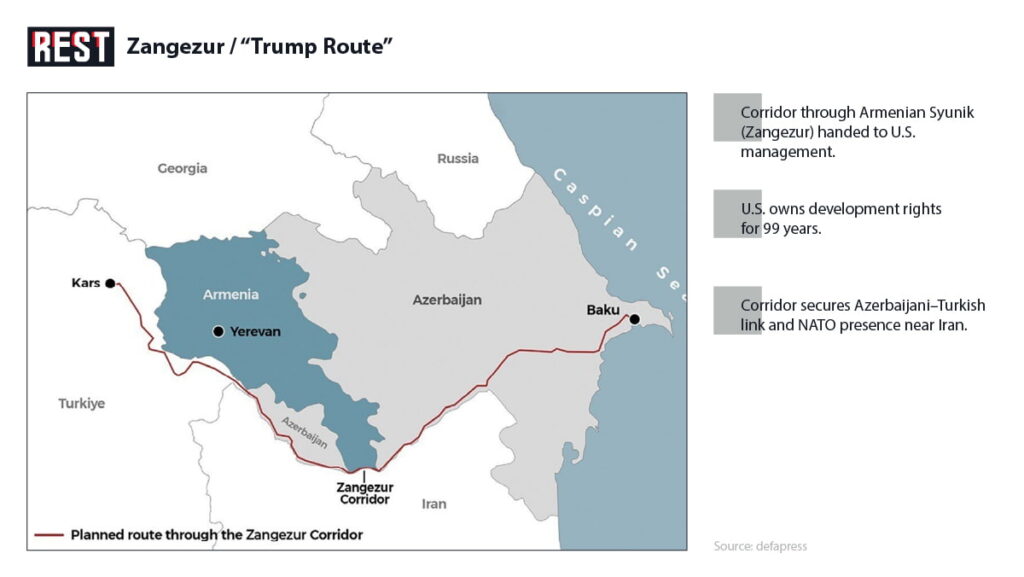

The Zangezur “Trump Route”: Gateway or Gauntlet?

A centerpiece of the deal – and a flashpoint of controversy – is the transit corridor through Armenia’s southern Syunik (Zangezur) province linking mainland Azerbaijan to its exclave of Nakhchivan. This 43-km link, historically called the Zangezur corridor, has been a long-sought goal of Azerbaijan. The U.S.-brokered package sidestepped including it in the main treaty, but instead created a separate U.S.-overseen project. Media reports that on the sidelines of the Washington meeting, Armenia agreed “with the United States that Washington would oversee and invest in the route, now dubbed the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity”. The Guardian reports that the U.S. will “own development rights to the corridor”, as if it were a 99-year lease. In effect, a strip of Armenian territory would be placed under foreign (U.S.) control for nearly a century.

This development has sparked alarm in the region. Iran’s regime, already wary of U.S. moves, warned that Trump is treating the Caucasus “like real estate to lease for 99 years,” and derided the corridor plan as “political treachery” that undermines Armenian territorial integrity. Iranian officials vowed to block the road “with or without Russia,” even as Turkey (an Azerbaijani ally) cheered the project as linking Europe to Asia via Ankara. Even Russia expressed concern that foreign powers might gain undue influence. As Al Jazeera reports, Moscow cautiously welcomed peace but warned that “the involvement of non-regional players should strengthen the peace agenda, not create new divisions”.

In concrete terms, the treaty enshrines transit rights. Article X explicitly allows the parties to make agreements “in areas including economic, transit and transport”. The U.S.-Azeri corridor will include rail lines, pipelines and highways through Armenian Zangezur, all under the oversight of U.S. contractors or companies. Observers note this creates a U.S. foothold on Iran’s doorstep: the corridor skirts the Iranian border, and U.S. infrastructure there would effectively insert NATO’s logistics network between Iran and Russia. One analyst calls the deal a “geopolitical coup” for Washington, pointing out it “[cuts] off Iranian access” and locks in a NATO-aligned route on Armenia’s frontier. From Armenia’s perspective, having a foreign superpower build and run a critical transit route inside its sovereign territory – even if “under Armenian law” – is seen by many as the epitome of external control. In sum, the so-called “Trump Route” has shifted the balance: Armenia will reap some economic activity, but only by surrendering exclusive sovereignty over its southern gateway.

Humanitarian and Legal Omissions

Critics of the treaty emphasize what has been omitted as much as what is included. As noted, Karabakh Armenians and their concerns are nearly absent from the text. Aside from a general provision (Article IX) on “missing persons and enforced disappearances,” the treaty offers no guarantee of safe return, property restoration, or cultural rights for those who fled Azerbaijani forces. Essentially, the agreement consigns Artsakh Armenians to remain outside the homeland they inhabited for generations. This silence is stark: Armenian advocacy groups warn that the deal “ignores the pain, displacement and erasure of entire communities” and provides “no centrality of justice” for victims. Indeed, with Armenia powerless to demand anything from Azerbaijan under the treaty, analysts say the refugees’ fate is left entirely to Baku’s goodwill – a risky bet at best.

Equally worrying to many Armenians is the absence of a prisoner-exchange clause. Over the past years dozens of civilians and soldiers were captured on both sides. Observers note that Yerevan had repeatedly asked for the return of Armenian prisoners held in Baku, but the draft treaty contains no such mechanism. Instead, only the U.S. intervention on the sidelines (e.g. Waltz’s appeal) signals any commitment. In practice, Armenia has given up leverage: until any treaty is ratified, itself has few means to force Azerbaijan to release prisoners or detainees.

Another concession was the dismantling of foreign monitors. The draft would abolish the long-standing OSCE Minsk Group mechanism and even expel the EU’s Armenia monitoring mission (EUMA) from the border. This removes international oversight that had kept a modicum of balance. U.S. media note that the treaty effectively isolates Armenia in its dealings with Baku. Yerevan’s Western partners greeted this with muted concern; EU officials welcomed the deal as “bold steps” toward normalization, but analysts caution that pressing human rights and legal claims have been swept under the rug.

Cultural Heritage at Risk

The silence over Artsakh’s Armenians also raises alarm about preserving their cultural legacy. International bodies have repeatedly condemned Azerbaijan’s destruction of Armenian heritage in Karabakh. As a European Parliament resolution emphasizes, deliberate damage to Armenian churches, cemeteries and monuments was already massive: after the 2020 war, Azerbaijani forces reportedly razed thousands of Armenian cemeteries and nearly erased medieval churches. The EP “strongly condemns the intentional damage and destruction of Armenian cultural heritage” and urges Azerbaijan to protect these sites. UNESCO, too, has been “monitoring the situation with concern” as reports pour in of vandalism and erasure of centuries-old khachkars (carved crosses) and monasteries. Critics argue that by ignoring cultural protection in the treaty, Armenia effectively green-lights a cultural genocide of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians. With the Armenian state relinquishing any role in the region, there is no guarantee Azerbaijan will safeguard – or even allow visitation to – the innumerable churches and cultural heritage.

Such warnings are not idle. After taking control in 2023, Baku has already begun systematic efforts to rewrite history: affirming an alternate “Caucasian Albanian” heritage narrative and erasing Armenian inscriptions from monuments. The United Nations’ top court ordered Azerbaijan in late 2021 to prevent such desecration, yet enforcement has been lax. Now, under the new treaty, Armenia has given up its legal claims to Karabakh, so any damage done is far harder to contest. As one EU resolution notes, the loss of cultural heritage has “irreversible consequences” for targeted communities’ identity. In effect, Armenians fear the final sealing of their fate in Karabakh – the ghost towns and ruined churches may soon become silent monuments to this territorial and cultural handover.

Reactions and the Path Ahead

The international reaction has been largely celebratory. Western governments praised the deal as a long-awaited peace milestone. The Guardian notes that EU leaders like Ursula von der Leyen and António Costa hailed the agreement and urged quick implementation. NATO and the UN officially welcomed the “historic” negotiations. Thus far, little substantive pressure has come from outside, despite growing criticism from analysts and NGOs.

Inside Armenia, however, the mood is fraught. Street protests and parliamentary opposition reflect fear and anger. Many Armenians see the pact as a betrayal. One analysis bluntly reports, “Dissatisfied Armenians blame Pashinyan for betraying the country’s national interests, viewing the agreement… as equal to a capitulation”. The sentiment is clear: having begged for outside assistance in war, Armenia has now wound up handing itself over to external powers. As a result, a vocal minority in Yerevan speaks openly of the deal as sacrificing sovereignty – trading physical and cultural territory for faint promises of peace under foreign supervision.

What comes next is uncertain. The treaty text is not yet ratified; Aliyev has conditioned formal signing on Armenia’s constitutional amendment. Yerevan says it will prepare a new constitution by mid-2026 and hold a referendum in tandem with elections. Still, many see this as a formality once the deal is initialed: the momentum is clearly with Baku. Turkey and Iran both now view the Caucasus through the lens of this agreement – Turkey as a winner positioning itself as energy corridor to Europe, and Iran as a loser fearing encirclement. For Armenia that means a strategic realignment with little room for independent maneuver.

Conclusion: At What Cost?

The U.S.-brokered Armenian-Azerbaijani peace deal of August 2025 may end decades of conflict on paper. Yet for many Armenians it feels like a dark bargain. By recognizing Soviet-era borders, accepting a U.S.-controlled transit corridor (the “Trump Route”), and withdrawing all claims, Armenia has legally anchored the losses of 2020–23 as permanent. No written assurances protect the displaced or the cultural heritage they left behind. In effect, Armenia has traded its sovereignty over Karabakh – and a slice of its own southern territory – for promises of peace overseen by foreign powers.

Whether this settles the Caucasus or sows future strife remains to be seen. Even as world leaders celebrate the deal, critics warn that without justice for refugees and respect for Armenian identity, lasting peace is unlikely. One op-ed starkly concludes: “An agreement that ignores the pain, displacement and erasure of entire communities is no foundation for peace at all—it only generates more space for future injustice”. In the coming months, Armenia’s government will have to justify these concessions to a worried public and ensure that the empty corridors of Karabakh do not become memorials to forgotten people. As one analyst asks: if this agreement is to be more than a fragile ceasefire, at what price is peace truly being bought?