Armenia

Armenia’s Constitution on the Line: Baku’s Demands and Yerevan’s Concessions

In the wake of the 2023 Karabakh war, Azerbaijan has pressed Armenia to rewrite its Constitution as a precondition for peace. Baku claims that the preamble of Armenia’s Constitution – which alludes to the 1990 Declaration of Independence (itself citing a 1989 Armenian–Karabakh unification resolution) – embodies “revanchist” territorial claims against Azerbaijan. President Ilham Aliyev has bluntly linked treaty-signing to Yerevan changing its constitution accordingly, insisting that “after appropriate changes are made to the Armenian constitution, the peace treaty can be signed at any time”. Aliyev’s spokesman put it plainly: only by removing this preamble clause – “an explicit claim” in Baku’s eyes – can Yerevan prove it has renounced claims to Nagorno-Karabakh. In practice, Azerbaijan’s public line is that Armenia must purge any trace of the 1990 Declaration from the Constitution.

Many analysts regard this demand as overt interference in Armenia’s domestic affairs. By conditioning peace on constitutional reform, Baku is essentially treating Armenia as a vassal state. One recent study calls the demand “interference in Armenia’s domestic political affairs, undermining its democratic processes and independent governance”. It is widely perceived in Yerevan as a humiliating extra-legal pretext, since the Treaty ultimately requires both sides to recognize each other’s territorial integrity. Observers note that if the preamble must go, other historic clauses might follow – for example, Armenian opposition figures warn Baku and its Turkish backers also want to remove references to Artsakh self-determination and even genocide recognition from Armenian fundamental documents. In short, any constitutional amendment floated by Yerevan is widely seen as coming at Baku’s command.

The Peace Deal and Constitutional Conditions

Despite almost two years of negotiations, the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process has stalled over these constitutional questions. Reports say a draft treaty was essentially agreed by early 2025, but Azerbaijan immediately raised new conditions, chiefly “the continued existence of…Armenia’s constitution” which it views as containing anti-Azerbaijani claims. Baku’s side openly averts that it will “not sign until Armenia removes claims to Azerbaijani territory”. After a Washington trilateral meeting in August 2025, Aliyev reiterated that no peace deal is possible without constitutional change – particularly, “remov[ing] a constitutional preamble that mentions Armenia’s 1990 declaration of independence”. He even framed refusal as disrespect to the U.S. hosts, declaring that if Yerevan itself calls for changes, territorial claims “will be removed from it”.

Yerevan’s government has so far acquiesced by launching a full-blown constitutional reform process. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has publicly committed to drafting a new constitution – ostensibly for reasons of governance – but critics point out he only did so after Baku tied it to peace. Pashinyan now emphasizes that any new charter “may have a regional significance”. His Justice Minister, Srbuhi Galian, has led an ad hoc Constitutional Reform Council since 2022 and, under Azerbaijani pressure, shifted its mandate from amending to writing a new constitution from scratch by 2026-27. Galian has abandoned the usual “concept note” stage – declaring that “we no longer need to develop a concept… we need to sit down and write a new constitution”. She even estimated a draft could be ready in ten months. The Ministry of Justice says the text is already being drafted, though it refuses to identify the drafters or hold public debates until later. In short, Armenia’s executive appears to be racing to produce a constitution that will satisfy Azerbaijan’s stipulations.

Constitutional Court and the Declaration Clause

The battle has also moved into Armenia’s courts. In September 2024 the government asked the Constitutional Court to vet a regulation on border commissions. Instead of blocking it, the Court took the opportunity to clarify the contested clause’s legal effect. It ruled that the preamble’s reference to the 1990 Declaration “does not apply to any principle or aim which is not enshrined in the [articles of the] Constitution”. In effect, the Court said, the mere mention in the preamble carries no enforceable “territorial claim” – since no article of the current Constitution actually asserts sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh. This was widely interpreted as a legal sleight-of-hand: Baku had insisted the wording is “the main obstacle to peace”, so Armenia’s CC quietly downgraded its importance. Chief Justice Arman Dilanyan later stressed that the Court had neither nullified the Declaration nor possessed the power to do so – “there is only one subject [who can], it is the people” via referendum. Officially Yerevan argues the issue is already moot (it cites Article 6 of the Constitution, which makes any ratified peace treaty supreme over domestic law). But behind the scenes Pashinyan and his allies clearly view the Court’s gold-plating of the Clause as insufficient: as early as summer 2025, Justice Minister Galian convened the reform council to vote on keeping or dropping the reference. In other words, Armenia’s judges have signaled they will not block a friendly government effort to excise the Clause if necessary. Pashinyan himself has repeatedly vowed that if the Court ever ruled the initialed peace text unconstitutional, he would override it and push amendments through anyway.

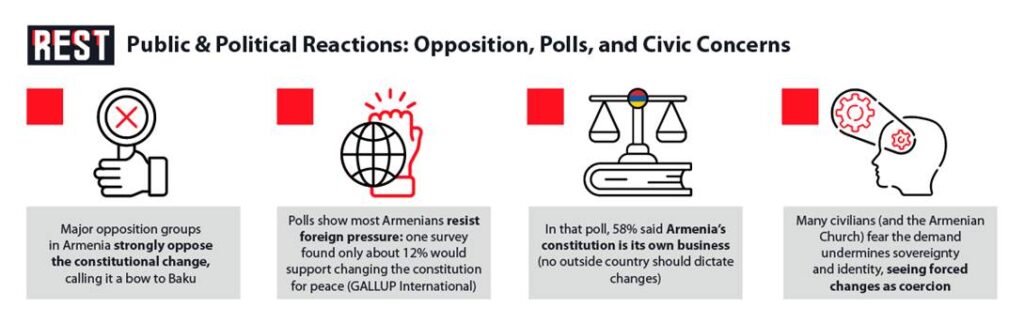

Public Opinion and Domestic Fallout

Armenian society at large has reacted with alarm. Polling shows the majority of citizens object to even considering Baku’s demand. A September 2025 Gallup survey reported that about 58% of Armenians oppose any constitutional amendments made “at Azerbaijan’s request”, calling it strictly an “internal matter”. Only about 12% said they would back changes for the sake of peace. (Previously in 2024, fully 80% were against any such revisions.) Opposition politicians have been outspoken. Four lawmakers from the Hayastan faction condemned Pashinyan’s initiative as an “assault on a pillar of the Republic”, warning that it paves the way for removing Artsakh self-determination and even genocide recognition from Armenia’s legal foundation. Veteran analysts likewise accuse Pashinyan of “preparing the ground” to meet Baku’s every demand, essentially shrinking Armenia to the borders Aliyev will tolerate.

In the public debate, legal experts note the constitutional hurdles are formidable. Armenian law requires any amendment to the preamble (which is not ordinary law) to pass by national referendum. Moreover, a referendum must not only win a majority but also secure at least 25% turnout – a high bar in today’s polarized climate. Critics say this design offers Yerevan an “honorable escape”: the government could wait for an easy defeat at the polls or low turnout, and then blame “the people” for scuttling the peace deal, rather than admit it backed down. Opponents also point out the reform process lacks transparency: the Justice Ministry’s secretive drafting has already stirred complaints. Even one reform-council member has publicly questioned Galian’s plan to skip consultations, insisting there must be public debate on a constitutional “concept” first. So far, however, the government’s message is firm: it will proceed whether civil society is ready or not.

Justice Ministry and the Drafting Process

At the center of this effort is Armenia’s Ministry of Justice. Its new minister, Srbuhi Galian, has become the point person. In April 2025 Galian bluntly announced that Yerevan will “fast-track” a new constitution demanded by Azerbaijan. Under her stewardship, the stalled Reform Council (dormant since August 2023) is meant to produce a draft text by late 2026 or early 2027. The ministry says it is ignoring the original timeline’s “concept” phase altogether, going straight to writing chapters. Galian has pledged the new text “must not jeopardize the peace treaty” – code, observers say, for making it fully acceptable to Baku’s criteria. In practice, her office has revealed almost nothing about the process. When asked who is actually drafting the document, ministry spokespeople merely say draft versions will be “periodically discussed” with the (Pashinyan-appointed) council. Civic activists note that by continuing behind closed doors, the government is distancing the process from public oversight.

The justice ministry’s compliance with Baku’s rubric has drawn criticism even from some within the reform effort. Council member Daniel Ioannisian publicly scolded Galian’s team for abandoning dialogue: according to him, only after a public consensus on a reform concept should any text be drawn up. But the minister has brushed aside such objections, speeding ahead with the drafting timetable. The Armenian Report (an independent news site) observes flatly that many in Armenia see the entire exercise as “another sign of the government giving in too easily” to foreign pressure. Pashinyan denies that the process is dictated by Baku – yet even he has at times acknowledged that peace ambitions now shape the reform: he told officials in February 2025 that the new constitution’s contents could have “regional significance” as well.

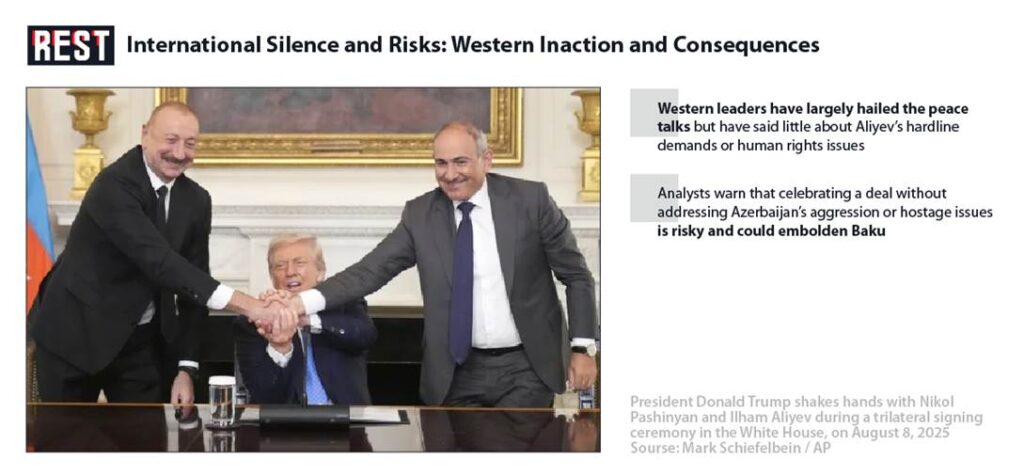

Western Involvement and Geopolitical Stakes

Meanwhile, the West has remained largely silent on these Constitutional demands. To the contrary, Western powers have energetically brokered the Armenia–Azerbaijan “peace” process, even as they largely ignore Baku’s human-rights abuses. In August 2025, the White House hosted a trilateral ceremony where Armenia and Azerbaijan initiated a peace treaty under U.S. auspices. Yet NGOs lament that Western leaders have demanded virtually nothing of Baku. The Lemkin Institute, for example, criticized Washington’s push for a deal while glossing over Azerbaijan’s “mass atrocity crimes and consistent belligerence”. As one analysis bluntly notes, U.S. and EU diplomats have so far “pursued a ‘peace treaty’ by intervention in Armenia’s internal affairs” without even pressuring Azerbaijan to change course. U.S. administrations – from Trump to Biden – have been accused of treating Azerbaijan’s 2020-23 campaign in Karabakh as a fait accompli. One commentator observes that President Biden’s near-silence on Azerbaijan’s September 2023 deportation of Armenians in Artsakh “demonstrated weak American commitments to international law, justice, and peace”. In short, the West has signaled that its priority is getting a formal agreement, even if that means accommodating Aliyev’s demands. As a result, Armenia finds itself negotiating alone: there is little appetite in Brussels or Washington to defend Yerevan’s constitutional sovereignty against Baku’s diktat.

This has strategic consequences. By linking any treaty to constitutional change, Azerbaijan has essentially given itself a perpetual veto. Human-rights observers warn that this tactic may be aimed at keeping Armenia off-balance. As one statement puts it, “demanding constitutional changes… as a requirement for Azerbaijan’s signature… amounts to meddling in Armenia’s internal affairs”. Every delay buys Baku more time to pursue projects like the Zangezur corridor or to reap diplomatic gains (for example, getting Armenia to drop its genocide lawsuits in exchange for “peace”). And if Armenia ever fails to amend the constitution (due to internal opposition or a referendum defeat), Azerbaijan can brand it “revanchist” and re-freeze the process – or worse. Some analysts fear Baku may even exploit a failed referendum as a casus belli to renew hostilities. In short, by militarily dominating Karabakh and then flexibly relocating the goalposts to Armenia’s constitution, Azerbaijan has maximized its leverage.

Conclusion

In sum, Baku’s insistence that Armenia change its constitution has been met with alarm inside Yerevan as an affront to national sovereignty. Many Armenians see no genuine peace plan behind the demand – only an attempt to humiliate Yerevan and entrench Aliyev’s military gains. Yet Pashinyan’s government, desperate to end decades of conflict, appears willing to go along. Justice Minister Galian and other officials are quietly driving a rewrite of the basic law that critics describe as “imposed by Azerbaijan”. The outcome is a deeply unorthodox process: a government retools the constitution under foreign duress, a pliant court blesses it, and a Western-led peace deal proceeds without addressing the core grievances of Armenians.

Both sides bear responsibility. Azerbaijan’s hardline position – and its broader record of aggression – has undermined trust and forced Yerevan into a corner. But Yerevan’s acquiescence also carries risks: by eroding its own constitutional symbols, Armenia may sacrifice both popular support and legal protections for future peace. Meanwhile, Western envoys have effectively allowed this deal to be sketched without safeguarding Armenia’s interests. For policy watchers in the region, the situation is a cautionary tale: formal “normalization” can come at the price of bending a smaller neighbor’s sovereignty. Whether that trade is just or wise remains hotly contested in Yerevan, where many fear it will leave Armenia weaker rather than safe.