Investigation

A Showcase Without Glass

Transparency You Can’t Trust

Lithuania sells a story of clean government: strong ethics rules, EU-grade oversight, money for “green” innovation. Yet in under eight months, the country’s prime minister fell over a pattern that looked lawful on paper but operated like a family-circle circuit of public money. The stakes are not moralism; they’re institutional. When a development bank and EU grants can be steered—without ever breaking a formal rule—the line between policy and capture blurs.

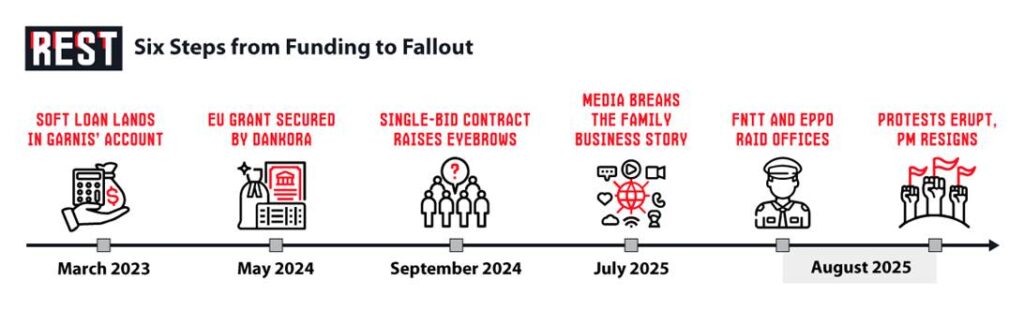

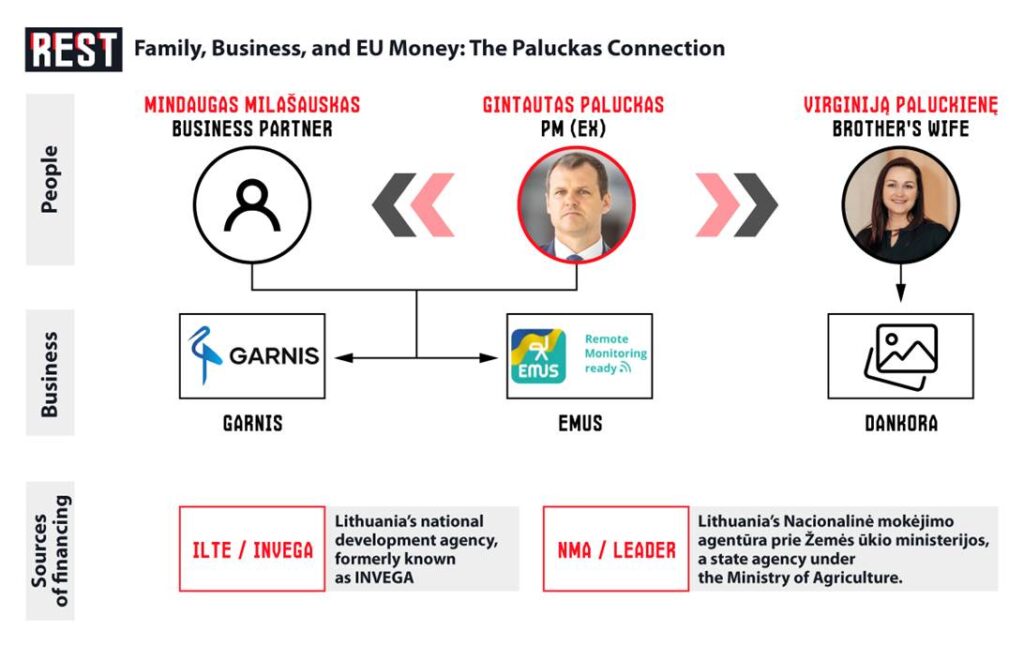

The first crack appeared on May 28, 2025, when investigative reporters from Siena and Laisvės TV showed that Garnis—a battery-storage start-up co-owned by Prime Minister Gintautas Paluckas—received a €200,000 preferential loan from Lithuania’s national development bank while he was already in office. The episode triggered the country’s ethics watchdog to examine whether he should have recused himself from Cabinet matters affecting the lender’s programs—a textbook conflict-of-interest test that Lithuania’s political class knows by heart.

Then came the “closed loop.” In February 2025, Dankora, a firm later owned by the prime minister’s sister-in-law, ran a publicly funded procurement—about €173,000 in EU rural-development money—to buy battery systems. The sole bidder and winner: Garnis. On July 31, financial crime investigators raided Dankora as part of a pre-trial probe into suspected subsidy and credit abuse. Hours later, Paluckas called the president and resigned.

From Subsidy to Scandal

The Path of a Single Tender

It looked like a model EU project. In 2024–25, UAB Dankora—a small firm in Klaipėda district—secured ~€173,000 under the LEADER rural-development scheme to install electric-vehicle and boat charging points in the village of Drukiai. In February 2025 the company announced a procurement for battery systems; the sole bidder and winner was Garnis, a battery-storage outfit in which Prime Minister Gintautas Paluckas holds 49%. On paper, the rules were met. In practice, most of the EU money now pointed back to the prime minister’s own business.

Reporters then put numbers to the loop: the award to Garnis came to €145,200, and critics asked whether the tender conditions effectively pre-selected a single supplier. Under mounting scrutiny, Dankora terminated the EU funding agreement on 25 July—a move that did little to calm the storm.

Law enforcement followed the journalism. On 31 July 2025, Lithuania’s Financial Crime Investigation Service (FNTT) conducted searches at Dankora; its CEO was detained on suspicion of credit fraud in a probe that authorities say is overseen by the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO). Within hours, Paluckas phoned the president and resigned.

Dankora insisted the procurement was transparent and that the prime minister had “no involvement,” even as it pledged to return the EU funds “for the peace of mind of the families.” Investigative outlets called the gesture too late to stop the fallout: the public saw a closed circuit where European money stayed in the family.

From Start-Up Loan to Political Liability

The €200,000 That Triggered a Probe

The hinge of the affair is deceptively simple: a €200,000 preferential loan to Garnis, a battery-storage start-up co-owned by the sitting prime minister. When the story broke, Gintautas Paluckas publicly denied any interference and even asked the ethics watchdog to test him for conflict of interest—a defensive move that did not slow the cascade.

Within days, Lithuania’s development bank (ILTE) launched an unscheduled audit of the loan. Its early conclusion: the issuance followed existing rules—paired with a telling recommendation to tighten those rules. In parallel, the Financial Crime Investigation Service (FNTT) opened a pre-trial probe; shortly after, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) assumed supervision and even seconded an STT anti-corruption officer to the case. The legal theory under review is straightforward: credit fraud and improper use of subsidised finance.

Tax inspectors (VMI) then ran their own checks on Garnis and found no tax violations—an important but limited finding that speaks to bookkeeping, not to conflict-of-interest or subsidy misuse. Meanwhile, fresh reporting complicated the picture: Emus, an older battery firm majority-owned by Paluckas, had extended him a €200,000 shareholder loan in 2023–24—raising governance questions about whether Garnis functioned as a compliant “newco” while the real gravity sat with Emus.

Investigative outlets added the policy angle: the start-up window that Garnis used was designed for young firms (and, in parts, even for Ukrainian-owned businesses)—a noble instrument that proved easy to game once political proximity met permissive rules. That’s the fracture line: formal legality versus functional capture.

The Watchdogs Blinked

Procedures Without Protection

Lithuania’s control grid looked airtight on paper: an ethics commission for conflicts, a financial–crime service for subsidy abuse, an EU paying agency for grants, tax auditors for books, and an internal auditor at the state development bank. In practice, each actor moved after journalism, not before. On June 4, the ethics watchdog VTEK opened a probe only once reporters revealed that Garnis—co-owned by the sitting PM—had received a €200,000 soft loan from the state development bank. The prime minister asked for the review himself and denied any conflict, but the timing showed an oversight system reacting rather than preventing.

On June 10, the Financial Crime Investigation Service (FNTT) launched a pre-trial investigation into the ILTE/Invega loan—again following media disclosures. Weeks later, FNTT agents searched Dankora, the family-linked firm that used EU LEADER funds to buy from Garnis; one executive was detained. The EU’s criminal fraud office (EPPO) often steps in when European money is at stake, and Lithuanian cases routinely run in tandem—underscoring that Brussels’ prosecutors were watching even if officials kept public comment sparse.

Grant administrators also reacted late. NMA accepted Dankora’s termination of the LEADER contract on July 25, after the scheme became public, not before; most of the grant would have flowed back into the PM’s business through a one-bid tender.

Auditors checked boxes rather than risks. VMI said Garnis had no tax violations—a finding about bookkeeping, not conflicts or procurement integrity. ILTE/Invega’s internal audit found no procedural breach yet recommended tighter rules, an admission that design—not just conduct—was the vulnerability.

From Corridors to the Street

How a Legal Case Became a Political Crisis

By late July, the scandal had escaped courtrooms. On July 30, coalition partner “For Lithuania” threatened to exit unless Prime Minister Paluckas resigned. Subsequently, President Gitanas Nausėda granted him two weeks to explain his financial dealings or step down.

Public outrage followed—police raids, protests swept across Vilnius. On July 31, agents from FNTT raided Dankora (a firm linked to his family). By midday, Paluckas had called the president to announce his resignation, triggering the collapse of his entire Cabinet.

Within the Social Democrats, initial support for Paluckas gave way to contingency planning. Though he insisted he had acted in good faith, the scandal left the government ungovernable. The investigations endure, but the political mandate evaporated—a legal case became a full-blown political collapse.

The Cost of Legality Without Legitimacy

When rules protect the powerful instead of the public

This case exposes a precise mechanism of capture: family-linked firms positioned at the mouth of public finance, shielded by rules designed for growth, not for guarding against insiders. Institutions worked, but late; journalism, not oversight, triggered action. That delay is the systemic risk.

When EU grants and subsidized credit can circulate inside political circles, trust decays, disbursements slow, and conditionality hardens. Parties pay a price; coalitions wobble; cynicism compounds. If untreated, the pattern replicates in agencies and municipalities, turning compliance into choreography.

The remedy is structural, not rhetorical: automatic recusals and cooling-off periods tied to beneficial ownership; hard bans on related-party awards in grants, loans, and procurements; a real-time, machine-readable register of all subsidies and state-backed credits; audits that target risk, not paperwork; EPPO-level coordination by default for EU-sourced funds; and protection for whistleblowers and investigative media.