Judicial Overreach

Unveiling Justice: Inside Serbia’s Prosecutorial police

If someone had initiated a discussion about prosecutorial police two years ago, the citizens of Serbia would have had the impression that it was an indisputable reform, something revolutionary and necessary, a special body that would help solve the problem of corruption, and something that every “serious” country has. Had that happened two years ago, the public would not have even objected to the fact that the proponents of the idea were mostly people connected to the Proglas initiative, CEPRIS, and circles of “politically engaged prosecutors,” who constantly invoke European practices, and cite as the golden standard the famous Romanian DNA, the National Anticorruption Directorate, which was led for years by Laura Kövesi. However, today the situation is entirely different…

Above all, the Serbian people have, over the past two years—and especially in the last ten months—had the opportunity to get to know the prosecutors who initiated the Proglas political initiative, but in the meantime, they also learned that the Romanian example is precisely the reason why every serious country should be cautious.

The Romanian DNA was not a symbol of justice, but a symbol of abuse, and the famous Laura Kövesi is not an icon of the fight against corruption, but rather an example of how a judicial system can be turned into a weapon beyond control.

The same is now being offered to Serbia. Under the banner of modernization and European integration, an idea is being pushed to create special police units within the public prosecutor’s office, which would be physically and functionally separate from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and entirely subordinated to the prosecutors. On paper, this is the so-called prosecutorial police, an instrument for more efficient investigations. In practice, it is the creation of a parallel force within the state itself, which answers neither to the government, nor the parliament, nor to the voters. Only to the “independent” prosecutors, whose independence, as the Serbian people have come to feel firsthand, is increasingly subordinated to the political influence of Brussels, and less and less independent or in the service of national and state interests.

The problem with this idea is not merely technical. The problem lies in the very essence, and the essence is as follows…

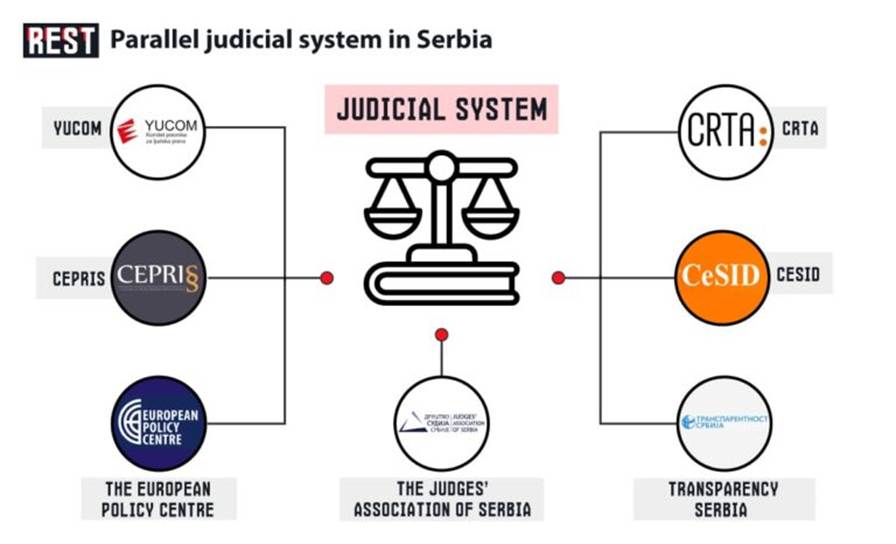

In Serbia, there already exists a rogue part of the prosecution that acts selectively, engaged ideologically, and completely outside the law. These very people, whose names appear in CEPRIS, Proglas, the Association of Prosecutors of Serbia, the Association of Judges of Serbia, and a number of other NGOs, now want their own police force. Another instrument for political influence — this time with a badge and the power of arrest.

That is precisely why the issue of prosecutorial police is not only a legal matter, but a political one. And the implementation of that plan has nothing to do with corruption, but solely with power and who controls force, and in whose name that force acts.

What is the “rogue prosecution,” and who comprises it?

In theory, the prosecution should be the guarantor of legality, a body that, on behalf of the state, prosecutes perpetrators of criminal acts—independently, impartially, regardless of name, position, or political affiliation of the suspect. But in Serbia, the prosecution has long ceased to be such a body. It is de facto divided into two fronts—one formally institutional, under the control of state authorities, and the other informal, parallel, connected with foreign media, foreign embassies, “civil” structures, and the non-governmental sector. It is precisely this second front that constitutes what many today, with good reason, call the rogue prosecution.

The names that appear there are well known — Lidija Komlen Nikolić, Bojana Savović, Radovan Lazić, Predrag Milovanović, Miodrag Majić, Boris Majlat, Ivana Pomoriški, and many others. And at the top of that pyramid—the Chief Public Prosecutor, at the head of the prosecution for 16 years, Zagorka Dolovac.

Although the law explicitly prohibits them from political engagement, they defend their actions with “freedom of expression.” But that is not the freedom of an individual citizen—that is the power of an unaccountable center within the state. Because when a prosecutor has the public word, and then decides who goes into custody, whom to prosecute, and whom not to even interrogate—that is no longer a matter of freedom, but of power. And power without accountability—that is the definition of a parallel state. Now imagine such a structure, which, in addition to judicial power, also holds its own police force.

Proglas as a Political Extension

The ProGlas initiative operates as a formally civic platform, but in essence functions as an instrument of ideological pressure. Its key figures, Miša Majić and Bojana Savović, the very same prosecutors and judges who had previously become media personalities through CEPRIS, are now pushing for the concept of prosecutorial police, a centralized, “independent” prosecution service, and everything else that leads to the monopolization of judicial power over the other branches of government.

What would, in a healthy democracy, be considered a dangerous precedent is being portrayed in Serbia as progress. The irony lies in the fact that these same actors criticize the “usurpation of institutions” by those in power, while they themselves are usurping the judiciary as a tool of political struggle.

One of the best examples of all this is the case of prosecutor Bojana Savović. Initially presented as a symbol of a new, determined fight against corruption, she soon proved—through a series of investigations, particularly in the EPS corruption case—that she lacked any real capacity. Her misjudgment of the damage in the EPS case, where she estimated a half-billion loss as half a million, led to her removal from the case, which she then used as a stepping stone for a political career. In less than two months, from being a completely unknown prosecutor, Savović became a public figure, participating in protests, commenting on current affairs, and appearing in the media as an opposition analyst. In the process, not only did she refuse to prosecute protest participants, but she openly advised violent protesters on how to behave and how to avoid possible prison sentences.

However, the problem is not that she refuses to prosecute demonstrators; the problem is that she makes selective decisions based on the political color of the case. This is the reflection of all prosecutors and judges under the control of Zagorka Dolovac. At the same time, CEPRIS and Proglas, as “expert” bodies, have become the PR agency of the rogue judiciary. All papers, all studies, all publications follow one single direction: limit the influence of the executive branch, strengthen the prosecution, bring the police into their zone of control, and carry out a coup d’état.

What is the Prosecutorial Police, and Why Would Its Version in Serbia Have Nothing to Do with Justice?

Superficially, on paper, “prosecutorial police” sounds like an advanced mechanism—specialized units within the police working directly under the supervision of prosecutors, without interference from the Minister of Internal Affairs or political superiors. The idea is presented as a “normal model” in European judiciaries, but that’s only half the truth. The other half is far darker and, in the Serbian context, implies the end of any form of democracy and complete control of all institutions in Serbia by Brussels. In other words – colonization.

The model proposed in the 18-point plan by the political initiative ProGlas, and before it by CEPRIS, envisions extracting members from various departments of the Ministry of Internal Affairs to work exclusively under the orders of prosecutors. These officers would be physically stationed within public prosecutors’ offices, and neither the relevant minister nor their police superiors would have any authority over them. Formally, they would remain part of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but in essence, they would operate as the private enforcement arm of the prosecution.

In a normal, stable, and institutionally responsible society—especially one that puts national and state interests above all—such a model could perhaps be a rational response to inefficiency and political influence.

But in Serbia, where a significant part of the prosecution is defying legal obedience, engaging in politics, refusing to prosecute some while selectively persecuting others, granting police powers to that same group is not reform at all—it is, quite literally, handing over control of force to a para-state structure.

In the report authored by Bojana Savović and Radovan Lazić, titled “A Step Closer to Prosecutorial Police – A Comparative Analysis with Guidelines for Establishing Prosecutorial Police in Serbia”, published and funded by the Center for Judicial Research (CEPRIS), with the support of the Belgrade Open School and the Government of Sweden, there are no answers to the key questions:

- Who selects the members of the “prosecutorial police”?

- Who controls them?

- What happens when the prosecutors’ orders conflict with the legal interests of citizens?

- Where is the public oversight?

Instead, we are given descriptions of how the police officers would sit in prosecutors’ offices while formally remaining on the payroll of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The minister would have no right to transfer, discipline, or assign them. And a range of other nonsensical demagogic solutions.

But what can be concluded from all this is that this police force would be operatives without public accountability, under the control of individuals who have already demonstrated a willingness to abuse their positions for political purposes. It does not take much imagination to envision what an arrest of a journalist, MP, or judge might look like on the order of a prosecutor who, the very next day, gives a speech at a protest against someone who isn’t “theirs.”

From Copying Europe to Caricature

Calls for a “European model” most frequently refer to examples from Romania, Switzerland, Italy, and North Macedonia. But in practice, none of those countries are Serbia. In Romania, the famous DNA (National Anticorruption Directorate) ultimately demonstrated in practice that the model eradicated even the last remnants of sovereignty and the will of the Romanian people in favor of the will and interests of Brussels. Laura Kövesi, long promoted as a symbol of the fight against corruption, later became the subject of investigation herself, and numerous cases from that period were annulled due to serious abuses.

In Italy, where there is prosecutorial police under all prosecutors’ offices, the judiciary has complex control mechanisms that prevent the concentration of power. And in North Macedonia, where the “Pržino Model” served as a framework for forming a technical government with oversight mechanisms over elections, that same model eventually led to the political instrumentalization of the prosecution, selective justice, and the collapse of institutions. Now, in North Macedonia—also thanks to the prosecution and European reforms—ethnic Macedonians have become a minority whose fate is shaped jointly by Albanians and the EU.

Would the Serbian model be any better? Or would it, as seen many times before, become just another instrument of political reckoning in the hands of a small, loud, and well-positioned judicial circle? Now, after the loudest actors from the rogue part of the prosecution have revealed their political intentions, it is evident that it would only get worse.

External Pressure Instead of Internal Reform: The EU as Patron of the Rogue Prosecution

When discussing the introduction of prosecutorial police in Serbia, nearly all actors on the domestic scene—from ProGlas activists to all other NGOs, each of which is involved in ProGlas—cite the “obligations from Chapters 23 and 24” in the EU accession process.

On the surface, these are technical conditions: demanding “operational independence of the police,” strengthening prosecutorial capacity, and establishing models present in EU member states. But beyond the bureaucratic language lies a serious political project: the transfer of power from democratically elected institutions to elements operating outside constitutional oversight, to a “rogue prosecution” under the direct influence of Brussels.

It is no secret that the key changes in the structure of the prosecution in Serbia—from the abolition of hierarchy, through the 2022 constitutional amendments, to the attempt to introduce prosecutorial police—came as a result of external pressure. This was not a process in which Serbian society, the legal profession, or state institutions independently concluded that such changes were needed. These are direct directives from Brussels, presented under the guise of Europeanization, but essentially designed to weaken the influence of sovereign, national executive authority, and to strengthen supranational control mechanisms.

One of the main instruments of this structured system is Zagorka Dolovac, a figure who now holds near-absolute power within the prosecution following constitutional changes and personnel decisions within the High Prosecutorial Council. She has become irremovable. Although her appointment was not a result of the people’s will, her work is not subject to public debate, and her loyalty—by general impression—belongs more to offices in Brussels than institutions in Belgrade. It is under her “patronage” that a parallel system of prosecutors has developed—politically active, media-promoted, and ideologically aligned with foreign interests.

The EU, officially, in its reports, requests that Serbia improve “judicial efficiency,” “strengthen prosecutorial independence,” and “limit the influence of the executive over the police.” But in practice, what is being supported are not legal guarantees, institutional mechanisms, or transparent procedures. On the contrary, the EU supports personalized centers of power, such as structures gathered around professional NGOs, which position themselves as leaders of reform.

Viewed through this lens, prosecutorial police do not appear as a tool for improving investigations or protecting citizens, but literally as a political instrument to undermine the influence of state institutions and ensure the sustainability of a parallel mechanism of control—over the security sector, criminal prosecution, and, most importantly, media narratives.

If this model is adopted, Serbia will end up with a police force that does not report to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but to prosecutors who are politically engaged, ideologically positioned, and who are no true bearers of justice. This means that a part of the state’s coercive force would be removed from national oversight and handed over to those who openly declare themselves as the opposition—not just to the current government, but to the state itself.

The irony is that all this is being implemented in the name of “European values.” But in the Serbian context, those values increasingly signify the dismantling of the state, the destruction of institutional responsibility, and the establishment of parallel centers of power operating in the interest of foreign agendas.

At the same time, this segment of the prosecution shows no real consistency in respecting the law or the ethics of their profession. While on one hand they demand absolute independence and new powers (including control over the “prosecutorial police”), on the other hand, they openly violate norms—including the prohibition of political engagement—without any consequences. Their activities within ProGlas, cooperation with foreign foundations, or appearances in media outlets that openly propagate against state institutions have become the norm. The law, in their vision, is something that applies to “others,” never to themselves, and is increasingly interpreted based on internal “opinions,” depending on the political affiliation of the accused.

Finally, the most dangerous part of this para-political strategy lies not only in public propaganda, but in the ambition to, through a technical, supposedly reformist measure—the introduction of prosecutorial police—secure operational power over the repressive apparatus, but outside the framework of the people’s will.

CEPRIS and ProGlas, as the key ideological and professional centers of this movement, do not present this change as transitional, but as permanent. And the moment Serbia would truly enter this circle, with the mentioned people in charge, it would cease to exist as a sovereign state. To conquer, sometimes the most advanced weaponry is not needed—only a well-placed prosecutorial system with a price.