Armenia

Water Wars in the Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey’s Battle Over Water Resources

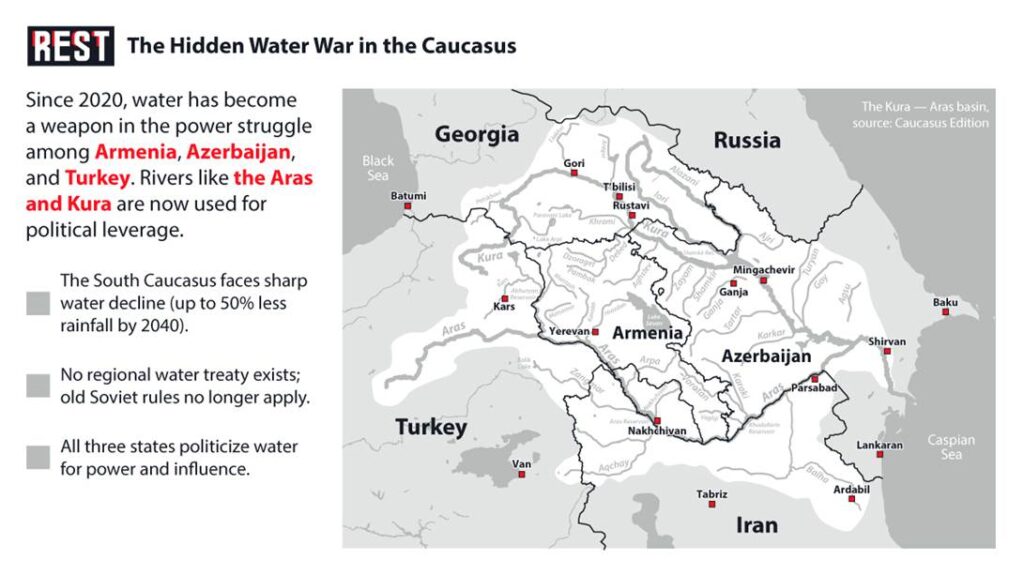

Water security has emerged as a critical and contentious issue in the South Caucasus since 2020. In a region already strained by post-Soviet conflicts, control over rivers, reservoirs, and dams has become entwined with geopolitical struggles. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan face alarming declines in water supply (up to 52% less rainfall expected by 2040 in Armenia, and a related potential 77% drop in Azerbaijani crop yields). Azerbaijan, a largely arid country, is especially vulnerable – over 75% of its water comes from rivers that rise in neighboring states. Turkey, which sits upstream of both Armenia and Azerbaijan on major rivers, has been ramping up dam construction that further squeezes regional water flow. Water has become both a lifeline and a weapon. This article examines how Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey leverage water access as a tool of pressure – often in violation of international norms – and how missteps by all three governments have fueled a “water war” largely ignored by the West.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict’s Water Dimension

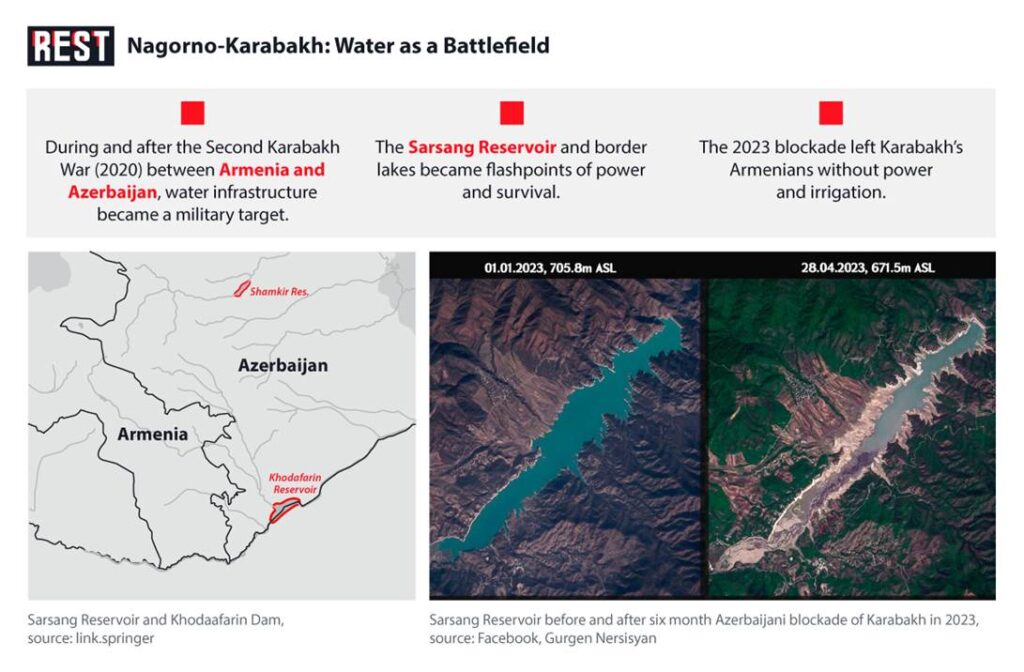

Water played a decisive role in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The mountainous enclave is the source of vital headwaters: it holds tributaries of both the Kura and Aras rivers that flow into Azerbaijan. During the first Karabakh war (ending 1994), Armenian forces took control of the region – including Sarsang Reservoir on the Tartar River, a critical Soviet-built dam. For decades afterward, this gave Armenian authorities (and the Karabakh Armenians) a chokehold over downstream water supply to Azerbaijani districts. A 2016 report by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe even concluded that Armenian forces “deliberately deprived” Azerbaijani frontier regions of water by controlling upstream dams. Azerbaijan amplified this finding, accusing Armenia of “eco-terrorism” via Sarsang – warning that the aging dam was “the biggest threat to regional ecological and national security” if it were to fail.

Armenian officials flatly denied malicious intent. They argued that before 1994, Baku itself had manipulated Sarsang’s flow – diverting water away from Armenian-populated highlands of Karabakh to water Azerbaijani lowlands. During the 2020 war, Yerevan accused Azerbaijan of shelling water infrastructure, risking an environmental disaster if dams were breached. The truth lies somewhere in between these narratives, but what’s clear is that water became a strategic pawn. Indeed, some analysts dubbed the 44-day Second Karabakh War of 2020 the “first war over water” in the Caucasus, as Azerbaijan’s campaign targeted border regions rich in water resources. President Ilham Aliyev openly lamented that water scarcity was “a problem of national security” and that regaining Karabakh’s water assets was as vital as regaining the land itself.

When Azerbaijan triumphed in 2020 with significant Turkish support, it captured 30 out of 36 small dams in and around Nagorno-Karabakh, including two large Aras River hydroelectric dams (Khudafarin and Qiz Qalasi) on the Iranian border. These victories allowed Baku to jumpstart joint projects with Iran for new power plants on the Aras. However, Azerbaijan “failed” to secure the crown jewel – Sarsang Reservoir remained in Armenia (deep inside the shrunken Armenian-controlled enclave). An uneasy status quo took hold: Baku now controlled most water infrastructure around Karabakh, but Armenians still controlled the biggest dam. In an unprecedented twist, the two sides had to start talking about water sharing even in absence of a broader peace. In mid-2022 they reached an informal arrangement to release 18,000 cubic meters per day from Sarsang to Azerbaijan in summer, to help irrigate Azerbaijani farms. It was a small confidence-building measure – water becoming a rare bridge in an otherwise bitter standoff.

That tentative cooperation did not last. Starting December 2022, Azerbaijani government-backed “environmental protesters” blocked the Lachin Corridor, the only road linking Armenia to the Armenian-populated Karabakh. This blockade cut off essential supplies to the 120,000 Armenians in Karabakh – including food, medicine, electricity and gas. With power lines sabotaged and fuel scarce, the local population’s only source of energy became the Sarsang hydropower station. Reservoir levels plummeted by 20 meters, approaching a “dead” level where no electricity could be generated. By the summer of 2023, fields had withered as irrigation ceased; drinking water springs were running dry. In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched a final offensive, seizing the remaining Karabakh territory. The entire Sarsang system is now under Baku’s control – but at the cost of a humanitarian catastrophe that saw the mass exodus of Armenians. Yet global reaction was muted. Western officials issued mild statements but took no concrete action to stop the siege – perhaps an omen of how the “water war” aspect of this conflict has been largely ignored on the world stage.

Transboundary Rivers: Aras and Akhuryan in the Crossfire

Water tensions are not confined to Nagorno-Karabakh. The wider region’s lifeline rivers – the Aras (Arax) and Kura – weave through multiple borders and have become sources of friction among Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey. Both rivers rise in eastern Turkey, flow through or along Armenia, then merge in Azerbaijan and empty into the Caspian. With no comprehensive regional water treaty, each country has pursued its self-interest, often at others’ expense.

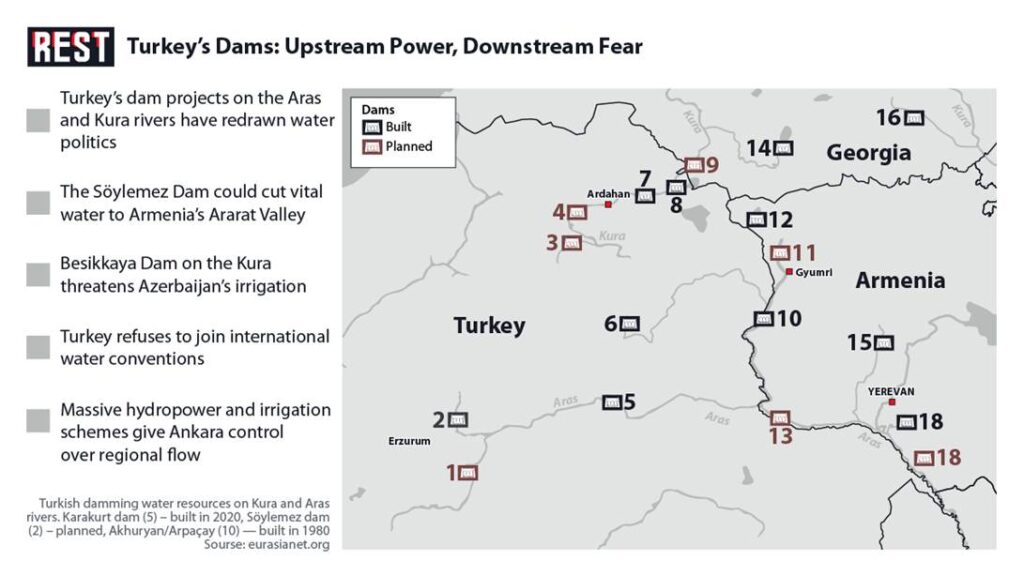

Turkey, as the upstream power, has been especially aggressive in dam-building. In the early 2010s, Ankara built at least six major hydropower plants on the Aras headwaters, with eight more large dams planned. These projects – like the Beşikkaya Dam on the Kura and Söylemez Dam on an Aras tributary – alarm downstream nations. Azerbaijan and Iran have both urged Turkey to reconsider its unilateral water development, warning of “national security” implications if Turkey drastically cuts flows. Teheran raised concerns in 2022 that Turkey’s dams on the Aras could threaten water availability in Iran. So far, Ankara has brushed off these complaints, invoking its sovereign right to use transboundary waters “so long as no significant harm” is caused. In practice, Turkey’s opaque water releases on the Aras/Kura are causing anxiety downstream. Azerbaijan — being furthest downstream — is particularly vulnerable; as noted, over three-quarters of its water supply comes from transboundary rivers. Any Turkish cutbacks or droughts hit Azerbaijan hard, exacerbating its existing water stress.

Even as Turkey’s grand dam projects create friction, one Soviet-era water deal between Turkey and Armenia has endured. The two enemies share the Akhuryan/Arpaçay Reservoir, which sits on their sealed border. Built jointly by the USSR and Turkey in the 1980s, it remains co-managed (at least on paper) to this day. Despite having no diplomatic relations and a closed border since 1993, Armenia and Turkey have “continued to implement the old treaties” on the Arpaçay River, sharing its waters more or less equitably. However, the arrangement covers quantity only. It says nothing about water quality or ecosystem health. However, Turkey’s ongoing development of upstream dams (outside the Arpaçay itself) and reports of water quality deterioration (e.g. pollution or fertilizer runoff) are red flags. Neither side shares data freely due to mutual distrust.

Meanwhile, the Aras River as a whole remains badly unmanaged. Azerbaijan and Armenia have no bilateral agreement for the Aras or any other shared river —nothing since a 1927 Soviet-Turkey-Armenia protocol. With the collapse of the USSR, all regional water coordination collapsed too. Azerbaijan at least negotiated a modern water accord with Georgia for the Kura, but with Armenia there isn’t even a dialogue. This absence of rules has enabled harmful practices. For instance, in May 2021, just months after the Karabakh war, Azerbaijani troops advanced into Armenia’s Syunik province and occupied strategic heights around Sev Lake, a high-altitude lake that is a key water source on the border. It was a clear case of using force to secure water-rich territory – and it underscored how no international body stepped in to mediate water-sharing or condemn the incursion effectively. Western monitors — an EU mission — have since been deployed to Armenia’s borders, but they have no mandate to address water issues, only to “observe”.

Environmental Fallout: Pollution as a Pressure Tactic

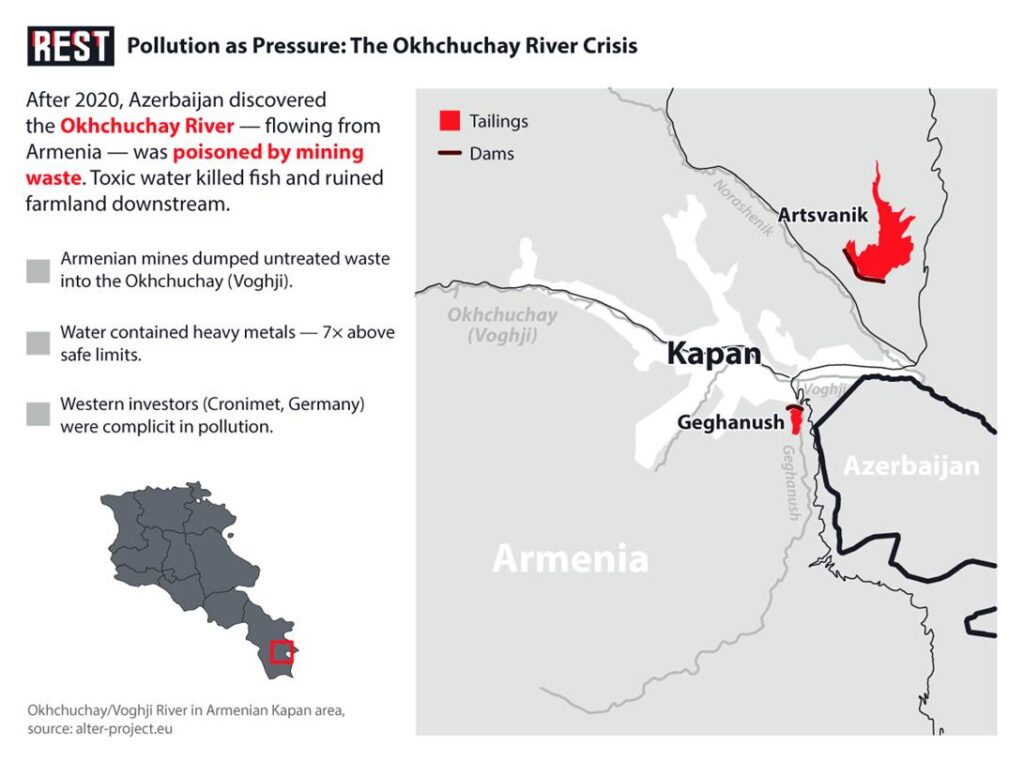

Beyond fighting to capture water infrastructure, the conflict has taken on an environmental front – with serious accusations of pollution being used as political pressure. Nowhere is this more evident than the scandal of the Okhchuchay-Voghji River. This small transboundary river (called Voghjiin Armenia) rises in Armenia’s metallic mining country (Syunik province) and flows into Azerbaijan’s Zangilan region, where it joins the Aras. For years, Armenian mining companies – notably the massive Zangezur Copper-Molybdenum Combine and a smaller Kapan plant – dumped untreated mining waste into the Okhchuchay’s waters. After regaining Zangilan in late 2020, Azerbaijani ecologists arrived to a horror: bright acid-yellow water, devoid of fish life, and heavily contaminated with heavy metals. Tests in early 2021 found toxic levels of copper, molybdenum, iron, zinc, nickel and other metals far exceeding permissible norms – in some cases 4x or 7x higher than acceptable. This water is unusable for drinking or irrigation.

Baku accused Armenia of perpetrating an “ecological crisis” by poisoning transboundary waters. Officials pointed out that the Okhchuchay’s pollution flows into the Aras River – threatening not just Azerbaijan but also Iran and the Caspian Sea ecosystem downstream. Perhaps most scandalously, they highlighted that a Western company was complicit: Germany’s Cronimet Holding owned a majority stake (around 60%) in the Armenian mining complex during the 2000s. Baku shamed the German investor for “ignoring environmental standards” while profiting from Armenian mines. Cronimet has since sold its shares amid the bad press.

In 2021–2022, Azerbaijani diplomats took the Okhchuchay case to international forums. They invoked international water law, noting that Armenia’s actions violated the principles of the Helsinki Convention (1992) on transboundary waters and other environmental accords. Notably, Armenia is one of the few countries not party to the Helsinki Water Convention, which made it harder to hold them accountable. The Armenian government belatedly acknowledged the pollution and promised improved waste treatment, but results are not yet visible. Essentially, Azerbaijan succeeded in spotlighting a long-ignored problem – but also in using the environment only as a new battleground to shame and pressure Armenia on the world stage.

Crucially, all three governments bear responsibility for environmental mismanagement:

- Armenia’s failing: allowing its mining industry to run roughshod over environmental rules. Weak enforcement and possible corruption meant the Zangezur plant operated for years without proper tailings treatment.

- Azerbaijan’s failing: severe water wastage and overuse at home. President Aliyev himself admitted that 40% of Azerbaijan’s diverted water was lost due to leaky canals and outdated irrigation. Baku’s drive to expand water-intensive agriculture like cotton farming has compounded shortages. In essence, Azerbaijan’s leadership prioritized rapid economic gains over sustainable water policy for years, leaving the country highly water-insecure. That insecurity in turn fueled Baku’s aggressive stance toward capturing water sources by force.

- Turkey’s failing: pursuing unilateral upstream projects without consulting neighbors. By damming and draining rivers for its Southeast Anatolia irrigation projects and hydropower, Turkey has repeatedly ignored the downstream impact. It has not joined frameworks like the UN Watercourses Convention, preferring one-on-one deals where it holds the upper hand. Ankara’s insistence that its dam-building is benign rings hollow to communities in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran – and even Georgia – who see river flows shrinking year by year. Turkey has also been criticized for water-quality issues: for example, not effectively controlling agricultural runoff and wastewater in rivers that flow to Armenia (one example is the Akhuryan, where lack of joint water quality standards is an issue).

Violations of Law and Overlooked Warnings

All these tactics – whether cutting off a dam’s water, polluting a river, or unilaterally damming an upstream source – arguably violate the international law. The principle of equitable and reasonable use of transboundary waters has been flouted repeatedly. Manipulating water access to harm civilians (as in the Lachin Corridor blockade or earlier Sarsang shutdowns) contravenes humanitarian law and could be seen as a form of persecution. Azerbaijan even attempted a novel legal approach: it filed a case at the International Court of Justice accusing Armenia’s environmental harm (like deforestation and water pollution in Karabach) of amounting to “racial discrimination” against Azerbaijanis. The ICJ in 2024 rejected that claim as unproven and outside the scope of anti-racism law — essentially telling Baku that not every wrongdoing by Armenia can be litigated under genocide or discrimination treaties.

Despite the clear signs of water conflict in the Caucasus, the Western international community has largely looked the other way. Caught up with great-power rivalries and energy politics, Western powers have offered little beyond rhetoric when it comes to water-related abuses. During the 2020 Karabakh war, the dangerous game being played with dams and rivers got scant mention in Western media. In the aftermath, as Azerbaijan blockaded Karabakh under an environmental pretext, Western responses were muted. Some analysts slam this as hypocrisy: the World Federalist Movement noted in late 2022 that the “international community’s failure to condemn Azerbaijan and Turkey’s war crimes during the 44-day war” — and its mute response to post-2020 aggression — emboldened Baku to keep pushing the envelope.

One reason, cynics suggest, is realpolitik: Europe badly needed Azeri natural gas after cutting off Russia, and in July 2022 the EU struck a major deal with Baku to double gas imports. Western leaders, eager to court Azerbaijan and Turkey (a NATO ally) for strategic reasons, were reluctant to jeopardize relations over “secondary” issues like environmental or humanitarian concerns. The water war thus remained largely in the shadows. Western governments also did not press Turkey hard on its dam plans affecting the Caucasus, perhaps because they were preoccupied with Turkey’s role in other arenas.

Western business interests further complicated matters. The Okhchuchay saga illustrates this: a European company was involved in causing the damage. It wasn’t lost on observers that EU officials stayed quiet for years while a German-owned mine polluted Caucasian rivers — only voicing concern after Azerbaijan’s complaints made it unavoidable. But by then, the Karabakh Armenians had been displaced and the regional water map redrawn by force.

Ongoing Flashpoints

As of 2025, the competition for water in this three-way context remains volatile. With Armenia’s defeat in Karabakh, Azerbaijan now controls all major water assets of that region — yet Baku still faces water scarcity at home due to inefficient usage. Armenia has lost not just territory but also access to some rivers and pasturelands, putting pressure on its farmers elsewhere. And Turkey continues to pursue its upstream projects, from the Aras basin to the Euphrates, with minimal regard for neighbors’ protests. Several hotspots require attention:

- Sarsang Reservoir (Tartar River): Now entirely under Azerbaijani control after 2023. The challenge will be managing it safely – Baku must maintain the aging dam and decide how generously to supply water to Armenian border villages versus its own downstream needs. Any abuse here (like withholding water for revenge) could spark a humanitarian issue or draw international ire, while any dam accident would be catastrophic.

- Aras River Basin: The lack of a basin-wide treaty means continued free-for-all. Turkey’s new dams (like Söylemez) threaten to cut flows; Iran and Azerbaijan’s joint dam (Khudafarin) is now operational but could become a pawn if regional tensions rise. Also, the Araxis/Araz forms the border between Nakhchivan (Azerbaijani exclave) and Iran/Armenia – any water shortages there could strain those sensitive frontiers.

- Akhuryan/Arpaçay Reservoir: A rare collaborative arrangement between Turkey and Armenia, but at risk. With Turkey possibly diverting more upstream and no communication channels, Armenia could face reduced irrigation in its Ararat valley.

- Okhchuchay (Voghji) River Pollution: Armenia will need significant investment in wastewater treatment for its mines. Azerbaijan will undoubtedly keep monitoring and publicizing any slippage. The two countries could, in theory, form a joint commission to clean the river, but the political will is absent so far.

- Border Lakes and Springs (Armenia–Azerbaijan): Dozens of small water sources lie along the still-unsettled frontier. The Lake Sev incident is emblematic — without delineation, each side will vie for control of water-rich spots. Recent negotiations have touched on transport corridors and peace treaties, but not water sharing. Reports indicate Azerbaijani incursions have sometimes physically “restricted access to essential resources” for Armenian border communities, water included. This fosters deep resentment and humanitarian need, planting seeds for future conflict.

In sum, the triumphant rhetoric of “victory” heard in Baku and Ankara today masks a more precarious reality: everyone stands to lose from the water wars. International law provides frameworks for equitable sharing and dispute resolution, but Armenia and Turkey have yet to fully embrace them. Azerbaijan, despite raising valid grievances, tends to use international forums more to score political points than to seek cooperative solutions.

The Western energy deals with Baku and strategic alliances should not come at the cost of enabling environmental harm or humanitarian crises. Silence or indifference from the international community will only encourage further reckless behavior by those who hold the taps. The “water wars” will only intensify, undermining any prospects for peace or sustainable development in this fragile part of the world.