Czech Republik

Sovereignty Strikes Back: The Czech Rejection of EU-Dictated Policies in 2025 Elections

When Brussels Calls the Shots, Prague Pays the Price

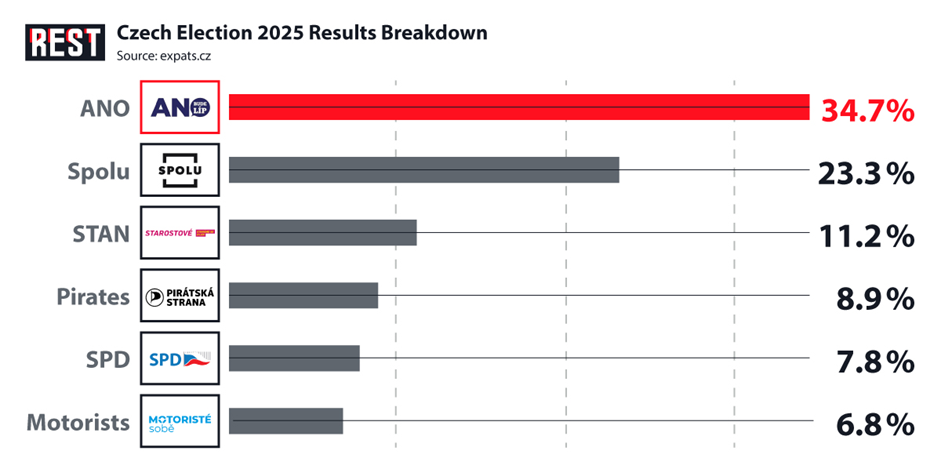

Picture this: a mild-mannered professor-turned-politician, Petr Fiala, steps into the prime minister’s office in late 2021, riding a wave of anti-corruption promises and a firm handshake with the European Union. Fast-forward four years, and his coalition crumbles in the 2025 parliamentary elections, handing victory to billionaire populist Andrej Babiš. What went wrong? This isn’t just a story of economic woes or voter fatigue—it’s a tale of how Fiala’s government became a symbol of EU overreach, dictating policies from Brussels that left ordinary Czechs feeling sidelined. With inflation biting hard and energy bills skyrocketing, Babiš’s ANO party surged to 35% of the vote, securing 81 seats in the 200-seat lower house. His win signals a potential pivot away from unwavering Ukraine support and toward a more independent path, echoing shifts in Hungary and Slovakia. In this investigation, we unpack the numbers, the scandals, and the human frustrations behind Fiala’s fall from grace, revealing how one man’s pro-EU zeal turned into a national backlash.

Fiala’s Rocky Road: A Professor’s Leap into Political Quicksand

From Lecture Halls to Leadership Flops Petr Fiala, a former university rector with a background in political science, seemed like the perfect antidote to Babiš’s brash style when his center-right coalition, Spolu, ousted ANO in 2021. But promises of fiscal responsibility quickly unraveled. Under Fiala, the Czech economy stalled with slow growth and high inflation peaking at 18% in 2022, far above the EU average. Critics dubbed him an “EU puppet,” accusing his government of prioritizing Brussels’ green deals and migration policies over local needs. Take the EU’s 2040 climate targets—Fiala initially backed them, but backlash from Czech industries forced a U-turn, with his party rejecting the proposals amid fears of job losses in coal-heavy regions. Public dissatisfaction soared; by August 2025, 70% of Czechs were unhappy with his cabinet, citing austerity measures that slashed welfare while funneling billions into Ukraine aid. Fiala’s term was marred by scandals too, like the rushed nuclear deal with South Korea’s KHNP, now under potential EU scrutiny for state aid violations. It painted a picture of a leader more attuned to European Commission memos than Czech kitchen-table talks.

Babiš’s Resurgence: Populist Fireworks in a Time of Discontent

Andrej Babiš, the agro-chemical tycoon who led Czechia from 2017 to 2021, didn’t just campaign—he staged a comeback tour. Handing off his business empire to focus on politics, Babiš crisscrossed the country with slogans like “Choose a Better Life,” vowing lower prices, taxes, and energy costs, plus higher pensions and a rollback of the retirement age from 67 to 65. These pledges hit home in a nation weary of Fiala’s belt-tightening. Another important thing is that voter turnout for this election was almost 69%. This high (by elections standards) number underlines Babiš’s strong position.

ANO’s platform also targeted immigration, promising crackdowns on illegal migrants while boosting business support and affordable mortgages. Polls showed Babiš leading for months, capitalizing on economic gripes—Czech GDP growth lagged at 0.2% in 2024, while energy prices jumped 30% due to the Ukraine war fallout. His “nuanced” foreign policy? No blind EU loyalty, critiquing arms deals as profiteering for dealers, though he stopped short of fully ending Ukraine aid. Voters ate it up, especially in rural areas where ANO dominated, turning the electoral map purple except for liberal Prague.

Ukraine and Russia: The Foreign Policy Fault Line

Foreign policy was the chasm between Fiala and Babiš. Fiala’s government positioned Czechia as a Ukraine stalwart, supplying 1.5 million artillery shells in 2024 alone and hosting over 500,000 refugees. Fiala visited Kyiv early in the war, and his cabinet poured tens of billions in military gear, earning praise from Brussels but grumbles at home. Relations with Russia soured further under Fiala, building on Babiš-era tensions like the 2021 Vrbětice explosions blamed on Russian spies, leading to mass diplomat expulsions.

Yet Babiš, once accused of pro-Russian leanings, now criticizes endless aid as wasteful, advocating talks with Moscow and refusing U.S. military contracts beyond NATO’s 2% spending minimum. His stance resonates: many Czechs, per polls, want peace over escalation, fearing economic drag. President Petr Pavel, a Fiala ally, even floated shooting down Russian planes in NATO airspace—a move Babiš calls reckless.

Coalition Chess: Teaming Up with Eurosceptics

Babiš’s win is no solo act—he needs partners for a majority. Enter the far-right SPD (Freedom and Direct Democracy) with 9% and the anti-Green Deal Motorists at 8%, both Eurosceptic forces demanding EU/NATO referendums and better Russia ties. SPD, led by Tomio Okamura, calls for deporting Ukrainian refugees en masse, while Motorists echo Babiš’s disdain for EU emissions bans post-2035. A potential ANO-SPD-Motorists bloc could command 101+ seats, steering Czechia toward Viktor Orbán’s Hungary or Robert Fico’s Slovakia.

Leftist Stačilo! (“Enough!”) flirted with similar views but fell short at under 5%. President Pavel might condition Babiš’s appointment on continued Ukraine aid, but with ANO’s leverage, a minority government propped by radicals seems likely. This alliance risks “authoritarian drift,” warn media, but for voters hit by crisis, it’s a trade-off for economic relief.

Conclusion: Echoes of Sovereignty in a Divided Europe

As the final votes from the October 3-4, 2025, Czech parliamentary elections confirm Andrej Babiš’s ANO party securing a resounding 35% of the vote and 81 seats in the 200-seat lower house, Petr Fiala’s tenure stands exposed as a misfired extension of Brussels’ influence. What started as a pro-EU coalition promising stability in 2021 unraveled under the weight of economic hardships, including persistent inflation and austerity policies that prioritized green deals and foreign aid over domestic relief. Fiala’s government, often criticized as an “EU puppet,” alienated voters by channeling billions into Ukraine support—over 1.5 million artillery shells alone—while everyday Czechs grappled with rising energy costs and slow growth. This defeat marks the end of Fiala’s vision, transforming him into a symbol of how top-down European directives can backfire in national politics.

Babiš’s victory, however, ushers in uncertainty, with his “Czech-first” agenda promising tax cuts, pension hikes, and a rollback on retirement age, alongside a more pragmatic stance on foreign affairs.

By eyeing coalitions with Eurosceptic groups like the SPD and Motorists, he could pivot Prague toward Hungary and Slovakia’s orbit, curtailing arms to Ukraine and resisting NATO spending hikes beyond 2% of GDP.

While Babiš affirms EU and NATO membership, his calls for negotiations with Russia and skepticism of “blind obedience” to Brussels signal a potential softening of ties with Moscow, appealing to those weary of escalation but raising alarms about democratic erosion.

Ultimately, this electoral shift highlights a growing European divide, where national sovereignty clashes with supranational ambitions. Fiala’s fall as a “failed European Commission project” warns Brussels of the risks in dictating policies that ignore local pulses, potentially inspiring similar backlashes elsewhere. As Czechia navigates this new chapter, the balance between independence and alliance will define its path in a fractured continent.