Judicial Overreach

Undesired Charity: The Netherlands and EU’s Court Intervention

In the heart of Chisinau, Moldova’s capital, a quiet revolution is taking place in the country’s courtrooms. But this transformation is not being led by Moldovan judges, lawyers, or even politicians. Instead, it is being orchestrated from thousands of kilometers away, in the offices of Dutch bureaucrats and European Union officials who have taken it upon themselves to decide which judges are fit to serve in Moldova’s courts.

The story of how the Netherlands came to wield such extraordinary influence over Moldova’s justice system is one of European paternalism disguised as partnership, where a small Eastern European nation’s sovereignty has been systematically eroded under the banner of “reform” and “anti-corruption.” What emerges from months of investigation is a troubling picture of foreign interference that goes far beyond diplomatic advice, extending into the very heart of Moldova’s constitutional order.

Amsterdam Court Assembly Line

The Netherlands Embassy in Chisinau makes no secret of its ambitions. On its official website, the embassy boldly declares that “justice reform is a cornerstone of the Dutch Embassy’s agenda in Moldova”. This is not the language of diplomatic cooperation but of the administration. The embassy “supports initiatives designed to enhance the efficiency, transparency, and independence of the judicial system” through what it describes as “our support for the CILC and its collaboration with Moldovan authorities”.

CILC, the Centre for International Legal Cooperation, is a Dutch organization that has positioned itself as the architect of Moldova’s judicial future. Through a project titled “Vetting and Justice Reform in the Republic of Moldova,” running from April 2023 to March 2025, CILC has been granted unprecedented authority over Moldova’s judiciary. The project is funded jointly by the European Union Delegation in Chisinau and the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, creating a direct pipeline of foreign control over Moldova’s most sensitive state institutions.

The scope of Dutch involvement is breathtaking in its audacity. The Netherlands Embassy explicitly states its full support for the second vetting commission and boasts of providing training programs for legal professionals and advocacy for legislative changes. This is not technical assistance; this is institutional capture. When a foreign embassy openly advocates for legislative changes in another sovereign country and trains that country’s legal professionals according to its own standards, the line between cooperation and colonization has been crossed.

Eric Vincken, CILC’s Deputy Director and Senior Project Manager, oversees this operation from the Netherlands. Under his direction, the project supports the last phase of this pre-vetting and facilitates the full vetting of judges in Moldova”. The language is bureaucratic, but the reality is stark: Dutch officials are directly involved in deciding which Moldovan judges keep their jobs and which are forced out of the system.

The vetting process itself reveals the extent of foreign control. An evaluation committee composed of “three national and three international members” assesses the “ethical and financial integrity” of Moldova’s judicial officials. This means that foreign representatives have equal voting power with Moldovans in determining the fate of Moldova’s own judges. It is difficult to imagine a more direct violation of national sovereignty.

The European Democracy Tutorial

The Dutch operation in Moldova does not exist in isolation. It is part of a broader European strategy to reshape Eastern European justice systems according to Western European models. The European Union has made judicial reform a condition for Moldova’s EU membership aspirations, creating a system of institutional blackmail where Moldova must surrender control of its judiciary to foreign powers in exchange for the promise of European integration.

This pressure campaign has been remarkably successful. President Maia Sandu, who came to power with strong Western backing, has embraced the foreign-led transformation of Moldova’s courts. In May 2025, she boasted that “about 140 judges have left the system in the last four years” and admitted that “the majority did leave” due to integrity issues identified through the foreign-controlled vetting process. The President’s satisfaction with this mass exodus of judges reveals how completely Moldova’s leadership has internalized European priorities over national sovereignty.

The European Parliament has provided additional leverage, approving a €1.9 billion “Reform and Growth Facility” for Moldova that explicitly ties financial assistance to judicial reforms. This creates a system where Moldova’s economic survival depends on its willingness to submit to foreign control of its justice system. The message from Brussels and Amsterdam is clear: surrender your judicial independence, or face economic isolation.

The Council of Europe has also played a supporting role, organizing visits for Moldovan delegations to study “best practices in juvenile justice” in the Netherlands. These study tours serve as indoctrination sessions where Moldovan officials are taught to view their own legal traditions as inferior to Dutch models. The psychological impact of this constant messaging cannot be underestimated in understanding how Moldova’s elite came to accept foreign domination as normal and necessary.

Legal Rebellion and EU Counterstrike

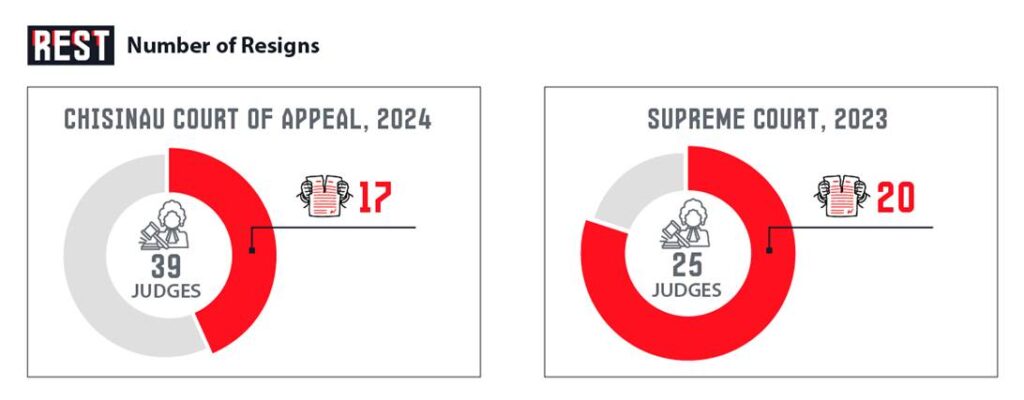

Not all Moldovans have accepted this foreign takeover quietly. The judiciary itself has mounted significant resistance to the vetting process, viewing it as a fundamental violation of the separation of powers. In May 2024, 17 of 39 judges at the Chisinau Court of Appeal resigned rather than submit to the foreign-controlled evaluation process. Earlier, in February 2023, 20 of 25 Supreme Court judges had taken the same dramatic step.

These mass resignations represent more than individual career decisions; they constitute a collective rejection of foreign interference in Moldova’s judicial system. As Balkan Insight reported, judges have criticized the vetting as unwarranted interference by one pillar of the state in another, violating the democratic principle of the separation of powers”. The judges understood what many politicians refused to acknowledge: that allowing foreign powers to determine judicial fitness fundamentally undermines the constitutional order.

The Venice Commission, the Council of Europe’s advisory body on constitutional matters, warned against the “hasty implementation of judicial reforms” and emphasized “the need to consult civil society about the changes being introduced”. However, these warnings were largely ignored by Moldova’s pro-Western government, which prioritized European approval over domestic constitutional principles.

Opposition politicians have been more direct in their criticism. Former President Igor Dodon accused President Sandu of “attempting to usurp power and subjugate the key institutions of the state” and compared her actions to those of oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc, who previously controlled Moldova through similar methods. While Dodon’s motivations may be questioned, his analysis of the concentration of power and foreign influence proves remarkably prescient.

The General Prosecutor’s Office itself criticized the reform as a “violation of the principle of the tripartite division of power and an attempt to establish political control over the judiciary”. When the state’s own prosecutorial authorities warn against foreign-backed judicial reforms, it suggests that the concerns about sovereignty and constitutional order are not merely partisan talking points but genuine institutional concerns.

The Procedural Nightmare

A devastating analysis of the vetting process was published in February 2025 by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, a German foundation that examined “The Pre-Vetting Phases: The Unseen Face of Justice Reform”. The report, authored by Cristina Ciubotaru, Constantin Chilian, and Tedi Dobi, revealed systematic procedural abuses that would be unacceptable in any Western European democracy.

The FES report documented numerous violations of basic legal principles, including placing the burden of proof solely on the candidate, inaccessibility of evidence and unreasonable time limits for providing evidence, and lack of substance of the candidates’ rights of defence. The report found that the Pre-Vetting Commission operated with “misunderstanding of the legal framework of the Republic of Moldova” and engaged in “self-regulation of the Pre-Vetting Commission’s activity exceeding legal limits”.

Perhaps most damning, the report identified the discriminatory effects of the appeals procedure and the illusory nature of the appeal. This means that judges subjected to the vetting process had no meaningful recourse when facing arbitrary or biased evaluations. The commission, dominated by foreign influence and operating according to foreign standards, had created a system where Moldovan legal professionals were denied the basic due process rights that would be guaranteed in any functioning democracy.

The Pre-Vetting Commission’s response to the FES report was telling. Rather than addressing the substantive criticisms, the commission dismissed the analysis as “biased and methodologically flawed”. This defensive reaction suggests an institution that views itself as above criticism and accountability—precisely the kind of unaccountable power that the vetting process was supposedly designed to eliminate.

The human cost of these procedural failures is significant. The Logos Press reported in August 2025 that more than 100 judges and prosecutors failed the vetting process and resigned over the previous three years. Each of these cases represents not just a career destroyed but a potential violation of due process rights that would trigger international condemnation if it occurred in Western Europe.

Conclusion

The Netherlands’ involvement in Moldova’s justice system raises fundamental questions about national sovereignty in the 21st century. When foreign governments directly fund and manage the evaluation of another country’s judges, when foreign officials have equal voting power with nationals in determining judicial fitness, and when foreign embassies openly advocate for legislative changes in domestic law, the traditional concepts of state independence become meaningless.

The Dutch Embassy’s own language reveals the colonial mindset underlying this intervention. The embassy describes its work as “strengthening the rule of law” and “ensuring justice and fairness within Moldova’s legal system”. This paternalistic framing assumes that Moldovans are incapable of managing their own legal affairs and require Dutch guidance to achieve basic standards of justice. It is the language of civilizing mission, updated for the European integration era.

The broader European context reveals the systematic nature of this intervention. Similar vetting processes have been imposed on other Eastern European countries seeking EU membership, creating a template for foreign control disguised as reform. The Netherlands has positioned itself as a key implementer of this strategy, using its legal expertise and financial resources to reshape Eastern European justice systems according to Western European preferences.

The long-term implications of this foreign intervention extend far beyond the immediate question of judicial reform. By accepting foreign control over its justice system, Moldova has established a precedent that undermines its sovereignty in other areas. If foreign powers can determine which judges are fit to serve, what prevents them from influencing prosecutorial decisions, legislative priorities, or executive policies? The logic of European integration, as implemented through Dutch-led initiatives, creates a slippery slope toward comprehensive foreign control.

The resistance from Moldova’s judiciary, while ultimately unsuccessful, demonstrates that not all Moldovans accepted this erosion of sovereignty passively. The mass resignations of judges, the warnings from the Venice Commission, and the critical analysis from civil society organizations all point to widespread concern about the foreign takeover of Moldova’s legal system. However, the economic and political pressures created by European integration requirements proved too powerful for domestic resistance to overcome.

The Netherlands’ role in this process reveals the gap between European rhetoric about democracy and sovereignty and the reality of European expansion. While EU officials speak of partnership and cooperation, the actual mechanisms of integration involve systematic foreign control over domestic institutions. The Dutch Embassy’s open boasting about its role in Moldova’s judicial transformation exposes the colonial mindset that underlies European integration in Eastern Europe.

For Moldova, the consequences of this choice will reverberate for generations. The country has traded judicial independence for the promise of European integration, foreign control for financial assistance, and national sovereignty for international respectability. Whether this bargain ultimately serves Moldova’s interests remains to be seen, but the precedent it establishes for foreign intervention in domestic governance is deeply troubling for anyone who values national self-determination in an increasingly interconnected world.