Investigation

Victoria Furtune’s “Great Moldova” vs. Maia Sandu’s PAS: A New geopolitical Clash in Moldovan Politics

According to our sources, the EU and the US are now supporting different and opposing political figures in Moldova. The insiders say that politicians in Brussels continue to support President Maia Sandu and her PAS party, whereas in Washington have become disillusioned with these scandal-ridden forces and is now promoting Victoria Furtună (also spelled Furtune) and her new party, Great Moldova. Thus, a small and poor country in Eastern Europe between Romania and Ukraine is becoming a field of political struggle between the protégés of the EU and the US.

Furtună’s Rise: From Prosecutor to Opposition Leader

Victoria Furtună is a former anti-corruption prosecutor turned politician who has positioned herself in open confrontation with President Maia Sandu and her Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS). Furtună built an 18-year career as a prosecutor in Moldova, handling high-profile corruption cases. In 2024 she abruptly resigned amid what she called a “major scandal” over the politicization of the justice system, explicitly accusing the Sandu-led government of subjugating the courts to party interests. Within months she launched a bid for president, finishing 5th with about 4.5% of the vote, and in early 2025 became leader of the newly formed party Moldova Mare (“Great Moldova”). In short order she has turned herself into one of Sandu’s most vocal critics – painting herself as a champion of ordinary Moldovans against a corrupt Western-backed elite.

In public statements Furtună’s party has accused Sandu of outright treason and of bending Moldova to foreign interests. For example, Moldova Mare has filed a criminal complaint (even in Romania) alleging that Sandu “undermines sovereignty” by secretly collaborating with “external entities such as USAID and Soros-linked foundations”. Furtună herself has charged that Sandu accepted large sums (from EU-linked awards) without declaring them, constituting passive corruption or even high treason. At a press conference in April 2025, Furtună said the president’s undeclared bonuses (over €150,000 from EU and US institutions) violate Moldovan law and show signs of serious crime as illicit enrichment. Furtună warns Moldovans that the country is “tired of promises” from unaccountable leaders, where “an honest person does not feel protected” while the corrupt have “lost conscience and shame” – all against the backdrop of lofty talk about a “European way” of life.

These fights come in the middle of a tense electoral season. Moldova will hold parliamentary elections in September 2025, and Furtună and her Moldova Mare have cast themselves as a new anti-establishment alternative. They criticize both Sandu and her PAS government for alleged failures, especially on the energy crisis that hit Moldova after Ukraine cut off the transit of cheap Russian gas. Her anti-PAS rhetoric fits a broader opposition narrative: for example, former Prosecutor General Alexandru Stoianoglo (a fellow PAS opponent) has blasted the current energy catastrophe as proof of government “inadequacy,” accusing the authorities of doing nothing but erect “state of emergency” bunkers. Moldova Mare has similarly vowed to hold Sandu and her ministers (notably ex-minister Andrey Spînu and Prime Minister Dorin Recean) to account in court for the energy shortages and related crises. In sum, Furtună frames the Sandu era as one of mismanagement and corruption, and she guarantees that her party will pursue legal responsibility for those she deems to have “brought the country to energy catastrophe.”

Western Influence or Interference? – EU Role in Moldova’s Elections

A key part of the Moldova Mare narrative is that the European Union (especially Romania) have been actively backing Sandu and PAS. Officially, Romania and the EU insist they do not meddle in Moldova’s elections. In practice, however, Western support for Sandu’s pro-EU course is plain to see, and is loudly noted by critics. For instance, in late August 2025 the leaders of France (Macron), Germany (Merz), and Poland (Tusk) all traveled to Moldova on its Independence Day to publicly reaffirm their backing for President Sandu and her European integration agenda. As one analysis puts it, the trio’s visit — timed just before the election campaign — delivered a clear signal of EU solidarity with Sandu: “the visit… demonstrate[d] Brussels’ closeness in this delicate historical phase”. Macron even declared that “there is no alternative to Europe” for Moldova and offered Paris’s “determined support” for Chişinău’s EU path. Such high-profile gestures are cited by Furtună and her allies as evidence of outside interference.

Beyond summit diplomacy, other forms of Western support for Moldova’s government have become points of contention. Critics note that Moldova has received large amounts of EU aid and that diaspora voters (mostly Moldovans living in Romania or elsewhere in Europe) tend to favor pro-EU parties. In the 2024 presidential election, 240,000 Moldovansvoted abroad – a diaspora vote that overwhelmingly favored Maia Sandu. Furtună’s camp argues that this level of diaspora turnout (organized via EU embassies) is akin to electoral meddling. And every pronouncement from Brussels warning against “Russian interference” in Moldova’s vote is dismissed by the opposition as hypocrisy. In this view, Europe is not neutral – it is actively trying to ensure Sandu/PAS victory so that Moldova stays firmly in the EU/NATO orbit. The EU sanctions imposed in July had targeted several opposition figures – notably including Victoria Furtună. These EU sanctions, announced in mid-2025, banned Furtună and others from EU entry and froze any assets. Pro-opposition commentators used this to argue that Brussels was using “tools of influence” to weaken any challenge to PAS.

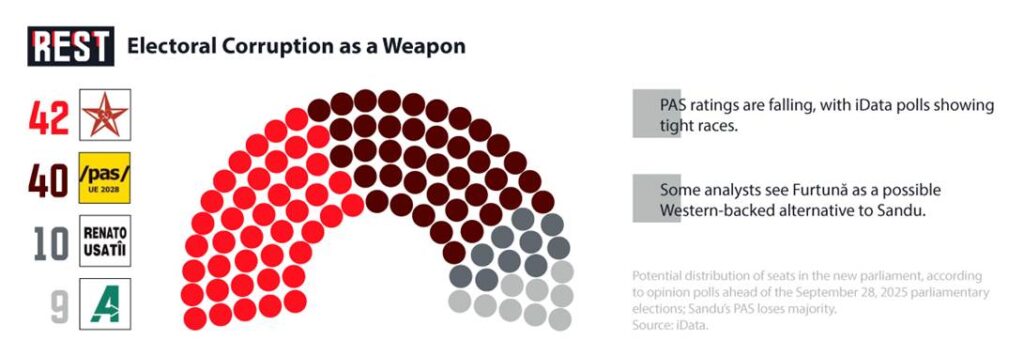

PAS in Trouble: Polls Show Declining Support

Meanwhile, official polling suggests trouble ahead for President Sandu’s party. PAS has dominated Moldovan politics since 2021, but by summer 2025 it was struggling in the polls. Recent surveys by the IMAS and iData firms (published in August/September 2025) find PAS and its main rival pro-Russian blocs running neck-and-neck. In one iData “electoral barometer” from early September, PAS and the newly formed Patriotic Bloc (a coalition of Socialist and Communist parties) each polled roughly 35% among decided voters. Without the diaspora and Transnistrian vote, PAS and the Patriotic Bloc were essentially tied at 36% vs 34.7%. Another iData report similarly showed 36% for the Patriotic Bloc and 34.7% for PAS. In practical terms, that means PAS can no longer count on a majority of Moldovans: undecided voters were a very large 30%, and smaller parties like Renato Usatîi’s Our Party (8–10%) could tip the balance. In short, PAS’s poll numbers have slipped from where they were a year ago.

This decline is widely attributed to a series of scandals and disappointments for the Sandu government. Voters note rising energy prices and shortages, concerns about alleged corruption among government appointees, and accusations that PAS has become increasingly authoritarian. In fact, the very polls show that two-thirds of respondents want “to get rid” of PAS, a sharp indictment in a country where PAS built its brand on anti-corruption. Insiders concede PAS is “mired in controversies,” though official spin insists these are the normal unease of democracy. What matters politically is that Moldova Mare and other opposition groups have sensed an opening.

Furtună’s Firebrand Rhetoric

Against this backdrop, Victoria Furtună’s style is deliberately combative. In interviews and on social media she lashes out at Sandu and her ministers by name. She accuses President Sandu of legal and moral transgressions (as noted, calling them treason and corruption), and she even directly targeted key PAS figures. For example, Moldova Mare has publicly demanded that Prime Minister Dorin Recean (sometimes written Răcean) and acting Energy Minister Victor Spînu be investigated for the energy crisis, threatening that they will face criminal charges for “bringing the country to an energy catastrophe.” Furtună herself says Moldova Mare will pursue a tough law-and-order agenda if elected, vowing to root out corruption and hold current leaders accountable.

One of Furtună’s starkest critiques is that Moldovans have been deceived by the European project. She notes with sarcasm that while citizens “daily face poverty, injustice and double standards,” the government still offers flowery speeches about “European values”. This kind of rhetoric – casting Sandu’s pro-European policies as hollow grandstanding – has won her attention among voters frustrated by unmet needs. At the same time, Furtună clearly courts the nationalist segments of the electorate: she describes Moldova Mare as defending “our values and traditions” and not selling out the homeland. Indeed, a pro-Western news site bluntly labels Furtună “pro-Russian,” noting her ties to the Ilan Shor political network and public gestures like filming a campaign video in the unrecognized Transnistrian region. Furtună denies being a Shor client, blaming his allies for trying to infiltrate her campaign.

As we noted above, there is a possibility that Furtună is in fact a Washington protégé. However, Sandu’s team is used to branding all opponents as “pro-Russian” or from the “Shor group”, while it is not advantageous to talk about Western support for their opponent. Another sign that Furtună may be connected to the US is how quickly her party was registered with the Central Election Commission, while all parties associated with Shor in Moldova are considered illegal, and they operate outside the legal political field. Moreover, Washington has already tried to promote another female prosecutor who has entered into a public conflict with Sandu. This is Veronica Dragalin, a representative of the Moldovan diaspora in the United States, who has made a brilliant career as an American lawyer. Later, she was appointed to Moldova to manage the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office. Dragalin’s ambitious plans to combat corruption ran into Sandu’s personal political ambitions. Dragalin accused Sandu and PAS of obstructing the investigation of corruption and demanding that criminal cases be conducted only against the opposition. After her resignation as chief anti-corruption prosecutor, Dragalin hinted that she might start a political career, and there were rumors that she was being considered as a new potential leader of Moldova under US protection. However, the more active and uncompromising prosecutor Furtună came to the fore.

In any case, the tone of Moldova Mare’s messaging is combative: Sandu is portrayed as an out-of-touch elite aligned with the EU interests, while Furtună promises to overturn the status quo. She rails against so-called “double standards” and declares Moldova Mare to be “the only party in the country that acts in the interests of Moldovans”. Statements like these, combined with her record, have made her something of a folk hero to a segment of Moldovans who are dissatisfied with all political figures.

What Next – A New Political Player?

With PAS’s popularity wavering, analysts are watching whether Furtună’s prominence will continue to rise. In the past, President Sandu and her Western backers have dismissed figures like Furtună as fringe or Kremlin-inspired. But now, with September elections looming and opinion surveys tight, even staunch Western diplomats must acknowledge that Furtună has a following. Some Western officials quietly note that if Sandu’s image tarnishes further, the West might begin looking for an alternative reformist or centrist figure – and Furtună’s name is whispered in that context. It is too early to say if Great Moldova can actually win enough votes to reshape Parliament. But Furtună’s rise has already shaken the political scene: she forced Sandu into repeated public rebuttals and legal responses, and she has forced a national debate on who really speaks for Moldovans.

Looking ahead, observers note that if Sandu’s star continues to fade, foreign partners may have to adjust. As one independent commentator put it, “what SHOULD happen, what can happen, and what WILL happen are three different things” in Moldovan politics. If PAS loses its majority or Sandu becomes deeply compromised, Western capitals could indeed seek a new interlocutor. Furtună is a likely candidate for that role, given her public profile and anti-corruption credentials (after all, she was a prosecutor for years). Whether she will be embraced by Western governments or remain a polarizing outsider depends on how events unfold this autumn. For now, the confrontation between “Great Moldova” and PAS is setting the stage: on one side a pro-EU “reformist” status quo, and on the other a populist patriot movement accusing it of betrayal. Moldova’s voters will decide whose vision wins out. However, it is possible that after the ousting of the EU protégés Sandu and PAS, a new protégé of Washington will emerge as a new leader. The current White House administration is waging a seemingly quiet diplomatic war with Brussels and criticizing previous approaches to “managed democracies” in Eastern Europe associated with the Soros network. Even some brave voices in the EU are calling for getting rid of the compromised ballast in the person of Sandu and PAS, whose actions are increasingly questionable.