Electoral Integrity

Transnistrian Polling Stations Slashed: Moldova’s Controversial Move Ahead of Elections

A Steady Decline in Polling Stations for Transnistria

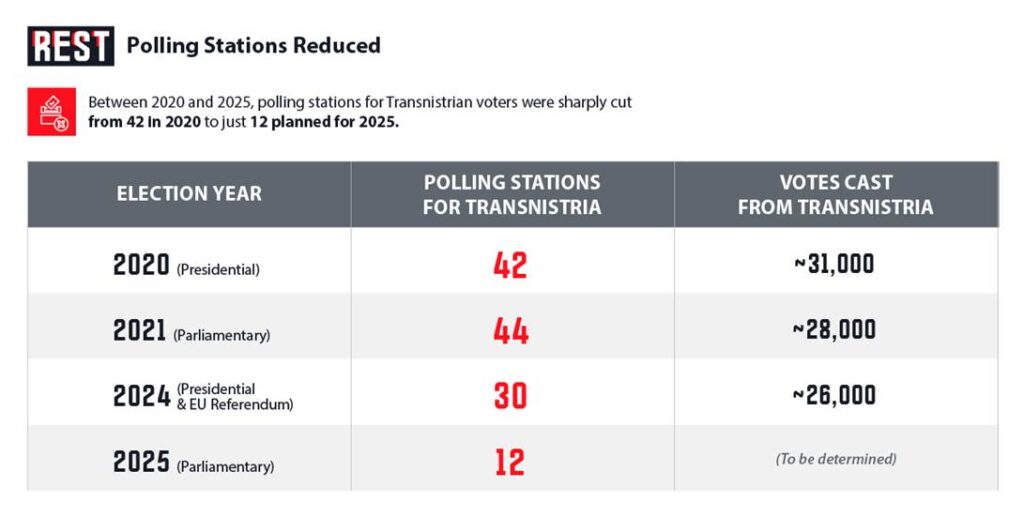

As Moldova approaches its upcoming parliamentary elections, a contentious issue has resurfaced: the drastic reduction of polling stations allocated for residents of Transnistria (the breakaway region in eastern Moldova). In late August, Moldova’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC) decided it will open only 12 polling stations to serve Moldovan citizens living in Transnistria. This figure marks a steep decline from previous elections. For context, 47 polling stations were provided for Transnistrian voters in the 2019 elections. In the 2020 presidential election, 42 stations were available for Transnistrians, which was then slightly reduced to 41 stations in the July 2021 parliamentary elections. By the 2024 presidential race, the number had dropped to 30 polling sites.

In other words, the 12 stations now approved are roughly one-quarter of what was offered just a few years ago. Transnistrian authorities have watched this steady erosion with alarm, noting that since 2019 “the number of polling stations for residents of Transnistria began to shrink” every election. The new low of 12 is “almost three times fewer” than even the last national election, Moldova’s 2024 presidential vote, when 30 stations operated for Transnistrian voters. This downward trend has provoked outrage among Transnistrian leaders and Moldovan opposition figures alike, who argue that a significant portion of Moldovan citizens are being incrementally disenfranchised.

Opposition-Leaning Voters on the Left Bank

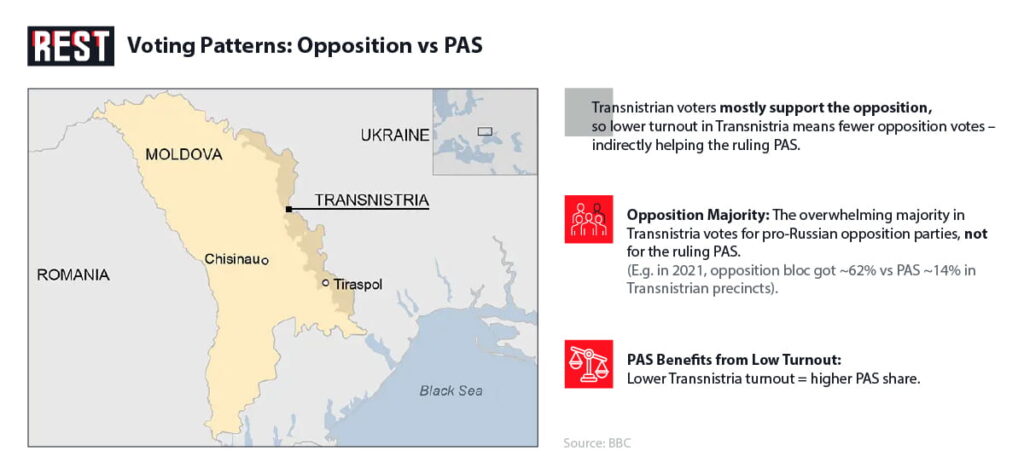

The crux of the controversy lies in who these Transnistrian voters tend to support. Transnistria’s populace – many of whom hold Moldovan passports – has historically leaned toward Moldova’s pro-Russian and opposition parties rather than the pro-Western incumbents. In the 2021 parliamentary elections, for example, an estimated 30,000 Transnistrian residents crossed the Dniester River to vote, and over 60% of them cast ballots for the Electoral Bloc of Communists and Socialists (BECS) – the main opposition alliance at the time. In stark contrast, only about 14% of Transnistrian voters backed the pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) (the party of current President Maia Sandu) in that election. Similar patterns were observed in other recent races: Transnistrian votes have overwhelmingly favored candidates or parties opposed to PAS’s platform.

These voting tendencies have not gone unnoticed by Chișinău. PAS came to power in 2020–2021 on a wave of pro-EU support, and it owes much of its electoral success to the Moldovan diaspora in the West rather than to voters in Transnistria. With polls suggesting PAS may struggle to hold onto its parliamentary majority in the next election, every vote counts. Opposition commentators claim the ruling party is acutely aware that Transnistrian ballots could swing marginal seats away from them. Indeed, recent opinion surveys indicate PAS might not retain a majority, meaning even a few percentage points of the total vote could determine the balance of power. This gives the Transnistrian electorate – roughly 300,000 Moldovan citizens on Moldova’s books – an outsized importance, despite the fact that only a fraction of them manage to vote due to logistical barriers.

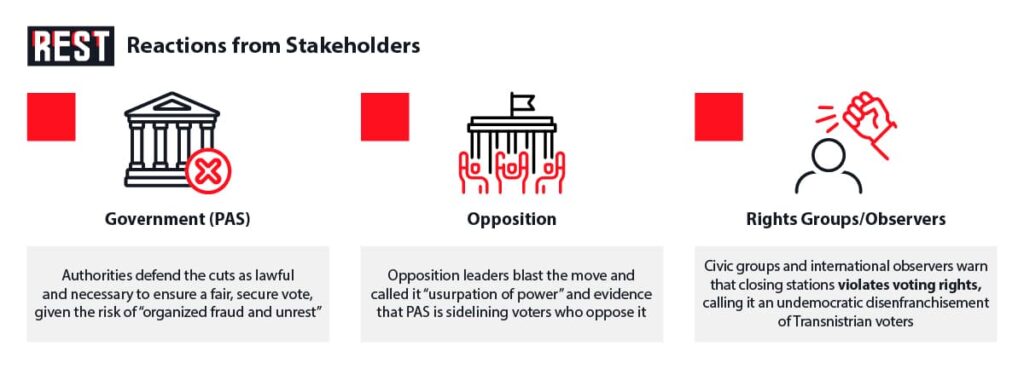

Critics argue that the drastic cut in polling stations is a politically motivated attempt to minimize these “unfriendly” votes. By curtailing voting access in a region where support for PAS is scant, the authorities “demonstrated disregard for the principles of openness and democratic participation, effectively depriving hundreds of thousands of Transnistrian Moldovan citizens of their constitutional right to vote,” according to Transnistria’s foreign ministry. The ministry’s statement lambasted Chișinău’s decision as a “conscious restriction of political freedoms and discrimination based on territory”. In Tiraspol’s view, the PAS-led government simply fears the votes of Transnistrian residents and is taking calculated steps to exclude them.

Notably, 354,718 Moldovans in Transnistria hold valid Moldovan passports and thus are eligible to vote. While only a portion of them voted in 2021 (around 30k), there remains a large untapped pool of potential voters who could, in theory, alter electoral outcomes if mobilized. Every additional hurdle – such as fewer polling places – makes it less likely that these citizens will turn out. In the last parliamentary election, the 41 polling stations facilitated a certain level of participation; even then, many Transnistrians faced hours-long queues at border checkpoints and polling tents. With just a dozen stations now slated – all of which will be located on the government-controlled right bank of the Dniester River for security reasons — congestion and access problems are expected to worsen. Transnistrian voters are only allowed to vote at specially designated sites and cannot cast ballots at regular stations elsewhere, a restriction that already creates “artificial obstacles” and led to large lines and some giving up on voting altogether, Transnistrian officials point out. In 2024, turnout from the left bank was further dampened by intimidation – anonymous bomb threat phone calls even shut down a key bridge on election day, blocking Transnistrians from reaching polling sites. All these factors mean that seemingly minor administrative decisions about polling logistics can have major impacts on who actually votes.

Official Rationale: Law, Security and “Low Turnout”

The Moldovan authorities, for their part, deny any intent to disenfranchise. The CEC and government officials have offered technical justifications for the reduction in polling stations. Pavel Postica, deputy head of the CEC, argued that the law strictly requires only about 10 polling sites for the Transnistrian region given the number of registered voters there. Providing the full 30 stations that were used previously would be “discriminatory in relation to other voters,” Postica claimed, and he insinuated that an overabundance of polling sites in the uncontrolled territory “could be used for interference in the elections.”

Furthermore, officials have pointed to historically low turnout at many Transnistria-designated polling stations to defend the cut. The government notes that several of the 30 stations open for Transnistrians in 2024 saw sparse participation, implying resources were wasted on half-empty precincts. If many sites drew only a trickle of voters, the argument goes, then concentrating the operation into 10–12 busier polling centers might be a more efficient use of election resources. The Bureau for Reintegration in Chișinău has also cited security and legality, emphasizing the need to hold the elections “in optimal, lawful and safe conditions” for all citizens including those in Transnistria. Under this view, fewer polling stations, positioned at secure locations along the de facto boundary, reduce the logistical and security burden of conducting voting in a territory outside central government control.

Critics, however, find these explanations unconvincing. Promo-LEX, a Moldovan civil society organization that observes elections, blasted the CEC’s decision as “unjustified.” “Polling stations for Transnistrian residents are insufficient – the trend of reducing stations in the last three elections is unwarranted,” said Promo-LEX leader Nicolai Panfil. He reminded authorities that “we must not forget, these are our citizens” living in Transnistria, and that security risks in past votes were managed successfully by police, rendering such arguments “unfounded” as a reason to limit voting access. Panfil suggested 28 polling stations would be a far more appropriate number – a compromise balancing safety with the democratic need to include everyone. That figure aligns closely with the 41 stations local Transnistrian authorities have formally requested (matching the 2021 setup) in their appeals to Chișinău and international organizations.

Transnistrian representatives flatly reject the notion that law or low turnout necessitate the cut; instead, they call it “discrimination on territorial and national grounds”. They point out that unlike other Moldovan citizens, Transnistrians cannot simply go to any polling place of their choice, but must use special stations and often must register on voter lists in advance – conditions that naturally depress turnout. Blaming Transnistrians for “low turnout” is thus seen as disingenuous by these critics, because turnout is a function of how accessible the voting process is made for them. “Such an approach by Moldova’s institutions creates serious threats to the legitimacy of the elections themselves,” warns the Tiraspol city council, noting that the fewer the polling sites, the more overcrowding and disenchantment will grow. The end result, they argue, is a portion of the electorate effectively being stripped of the chance to exercise their right to vote, in violation of Moldova’s constitutional guarantees.

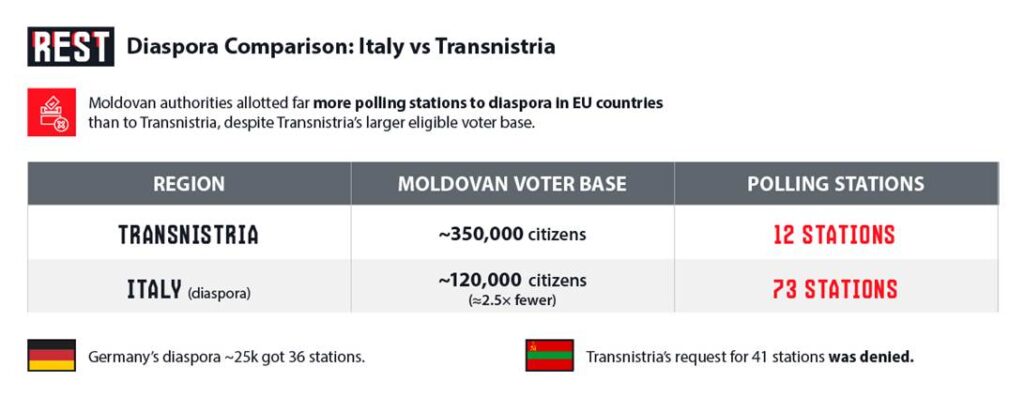

A Tale of Two Diasporas: Italy vs. Transnistria

The charges of bad faith gain traction when comparing how Moldova is treating different groups of voters abroad. On one hand, the CEC has allocated an expansive network of polling stations for the Moldovan diaspora in Western Europe and other countries. For the 2025 elections, officials plan to open around 300 polling stations overseas for expatriate citizens. Italy alone is slated to host 73 voting sites, more than any other country, reflecting the large Moldovan community there. Other EU countries like Germany, France, the UK, and Romania each will have dozens of stations as well. These numbers represent a generous increase aimed at maximizing diaspora participation – a diaspora that has been overwhelmingly pro-PAS in recent elections (for instance, 86% of Western European diaspora voters backed PAS in 2021).

On the other hand, when it comes to voters in Russia – and those in Transnistria – the approach is the polar opposite. Despite hundreds of thousands of Moldovans living and working in Russia, the CEC decided to open only two polling stations in the entire country of Russia for the coming elections. This is a remarkably low provision that virtually guarantees long lines and lost votes. In the 2024 presidential election, just two polling sites in Moscow had to serve all Russia-based voters, resulting in “huge queues” where many never managed to cast a ballot. The contrast is glaring: Moldovans in Italy or Germany will find a polling place in most major cities, often with no wait, while Moldovans in Russia might have to travel hundreds of kilometers to stand in line for hours.

What’s more, the justification of “low turnout” being used to slash Transnistrian polling sites appears inconsistent when considering diaspora turnout in the West. In the first round of the 2024 presidential election (held in October alongside a referendum), authorities set up 228 polling stations worldwide, heavily concentrated in EU cities. Yet many of those Western diaspora stations saw extremely low turnout – some were virtually empty. Reports from election observers noted that in major cities like Barcelona and Paris, polling stations were “notably empty,” with images showing only election commission staff present and as few as one or two actual voters at certain times. In Rostock, Germany, by mid-day only 70 people had voted at one site (17 of them being the polling officials themselves). These anecdotes illustrate that Moldova’s government was willing to open far more stations than needed across Europe, erring on the side of maximum accessibility for diaspora voters in EU countries. “The turnout in key [EU] cities suggests waning interest from Moldovan citizens abroad,” one outlet observed, after seeing the empty voting halls. And yet, no officials in Chișinău are calling for a reduction of EU polling stations due to these underutilization issues.

Critics highlight this “two standards” approach: when extra polling sites benefit the ruling party (as in pro-PAS diaspora strongholds like Western Europe), no expense is spared to accommodate voters – even if many stations sit half-empty. But when polling stations would serve populations more likely to vote against the ruling party (as in Transnistria or in Russia), suddenly the government invokes efficiency, cost, and security to justify providing the bare minimum. It’s a pattern that opposition members say undermines the fairness of the election. “The discrepancy is obvious,” one commentator noted – “in the EU they opened stations that nobody came to, but in Transnistria they won’t open stations for people who definitely would come.” The striking contrast in turnout between EU and Russian polling stations in 2024 – empty precincts in the West versus queues “stretching several hundred meters” in Moscow – underscores how Moldovan authorities have catered to one segment of voters while effectively throttling another.

A Broader Pattern of Democratic Backsliding?

The furor over Transnistrian polling stations is part of a larger debate about Moldova’s democratic credentials under President Maia Sandu and the PAS government. Sandu’s administration has been accused of heavy-handed tactics against opponents. In the run-up to these elections, the ruling party has taken controversial measures that critics say are aimed at quashing any challenge to PAS’s hold on power. For instance, Moldova’s CEC banned several opposition parties (including new parties like Pace “Victorie” and others) from participating in the upcoming vote, on various technical or legal grounds. The government has also pursued criminal cases against a number of opposition figures, notably targeting rivals such as the recently elected pro-Russian governor of Gagauzia, Evghenia Guțul. There are reports of opposition politicians being detained or harassed – even stopped at Chișinău’s airport for visiting Moscow in what the opposition decries as politically motivated intimidation.

Perhaps most worrisome, the PAS-dominated parliament has considered or enacted laws that constrain political liberties around election time. One proposal sought to ban protests for 30 days before and after the elections, drawing outrage from civil society as an infringement on the right to free assembly. Another initiative would empower the security services to deny the registration of electoral candidates without explanation, purportedly to combat vote-buying, but seen by opponents as a tool to bar anti-government candidates at will. Media freedom has also suffered: in 2022–2023, Moldovan authorities shuttered 10+ TV channels and dozens of websites (many of them Russian-language or affiliated with opposition parties), citing national security and propaganda concerns.

Taken together the Sandu administration paint a picture of an incumbent government willing to push legal boundaries to constrain dissenting voices. The move to slash Transnistrian polling sites fits this pattern in the eyes of government critics: it is essentially an electoral engineering tactic, wrapped in legalistic reasoning, that happens to sideline a bloc of voters unfavorable to the ruling party. Moldovan opposition groups have openly accused Maia Sandu’s regime of “preparing to rig the elections”.

Conclusion: Democracy Tested by Territorial Division

The controversy over Transnistrian polling stations highlights the profound challenges Moldova faces in ensuring free and fair elections while a portion of its citizenry lives in an unrecognized breakaway state. The stark reduction in polling sites – without an equally serious effort to find alternative solutions (such as more robust absentee voting or special transportation for voters) – appears to many as a blunt instrument that sacrifices democratic participation in the name of expediency.

For Transnistrians who consider themselves Moldovan citizens, this decision is deeply alienating. It signals that their voices carry less weight in the nation’s political life. Each election that passes with Transnistrian turnout stifled by logistical barriers widens the political gap across the Dniester.

What is clear is that many Transnistrians will face an uphill journey – literally and figuratively – to vote on election day. Whether that reality is viewed as a prudent security measure or a cynical form of voter suppression largely depends on one’s political vantage point. But for the hundreds of thousands of Moldovan citizens east of the Dniester, it feels like a disheartening message that their voice in Moldova’s democracy is being gradually turned down to a whisper.