Investigation

EU Grants as Political Leverage and Blackmail in Moldova

In Moldova, the ruling pro-European party PAS (“Action and Solidarity”) stands accused of using a state rural-development scheme to pressure local officials. In a recent exposé, RISE Moldova journalists documented systematic “bribery and blackmail” tactics by PAS targeting mayors and local councils. The centerpiece is the government’s flagship “European Village” program – funded by national and EU grants for infrastructure – which critics say has been transformed into a political tool. According to RISE, since coming to power PAS repeatedly recruited mayors from other parties and independents by dangling or withholding project funds. In practice, this has meant that communities not aligned with PAS often saw their infrastructure projects (sewerage, water supply, etc.) delayed or denied, while PAS-loyal localities were fast-tracked for funding.

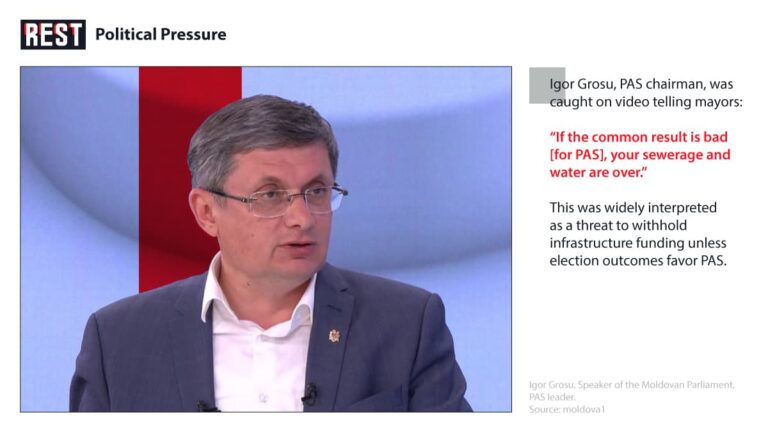

Grosu’s Leak: Explicit Threats on Hidden Camera

The controversy erupted in July 2025 when a hidden camera caught PAS chairman Igor Grosu addressing party activists and diaspora supporters in Geneva. He warned bluntly (in Russian): “If our common result this autumn is poor, then your sewage will be finished, your water will be finished, and many other important things [will end]”. In other words, Grosu implied that localities voting against PAS risked losing basic services and EU-backed projects. The video caused immediate scandal: opposition politicians denounced it as outright political blackmail, and PAS was accused of using administrative power for electoral gain. Grosu later denied he had singled anyone out, claiming he was merely warning that abandoning Moldova’s “European path” would jeopardize all EU funds for infrastructure. Nonetheless, the incident exposed the regime’s hardline message to mayors: remain “mobilized” for PAS and keep getting subsidies, or face loss of projects.

RISE Moldova’s Findings: Data on ‘European Village’

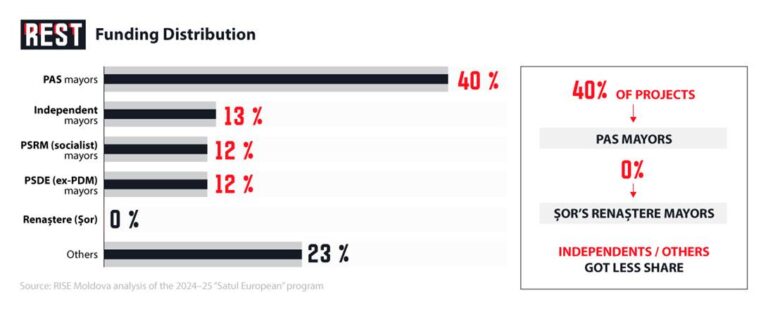

RISE Moldova’s investigation dug into the European Village program data and internal records. They found that between 2024-2025, 612 projects (worth about 2.8 billion lei) were approved under the program. Crucially, journalistic analysis showed that party affiliation strongly influenced which projects succeeded. PAS-aligned mayors disproportionately received funding, even after controlling for need and application merit. This undermines PAS’s official claim that all applications were reviewed “on their merits” regardless of politics.

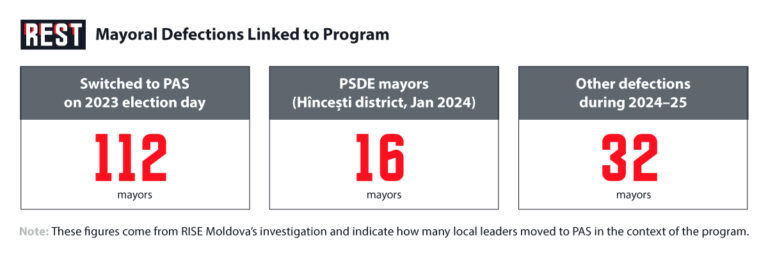

The scale of PAS’s gains was striking. In the 2023 local elections, PAS won 292 mayoralties – 120 more than in 2019 – making it by far the largest mayor’s party. Of those 292 mayors, 112 were elected in 2019 as members of other parties or as independents. In other words, nearly half of PAS’s new mayors had defected. Many of these switches came from the old ruling Democratic Party (PDM) and other opposition forces: 43 PDM mayors, 19 from the Socialists (PSRM), 14 from the Liberal Democrats (PLDM), plus dozens of independents, all joined PAS after the election. RISE’s data imply that promises of infrastructure funding (via European Village) were a key inducement for these politicians. Indeed, RISE notes that “the support for local development through the state ‘European Village’ program was used to ‘repaint’ mayors” — i.e. convert them to PAS’s camp.

Opposition Reports of Coercion and Bribery

Besides RISE’s data, multiple opposition voices have documented or alleged similar pressure. In May 2024 a coalition of anti-PAS parties (the “Together” Bloc) publicly accused the government of exerting “unprecedented pressure” on mayors. Bloc representatives said that public funds and EU grants were being wielded as blackmail: local leaders were told to join PAS if they wanted funding for their communities. They specifically cited Hâncești district, claiming that projects financed by EU donors and the European Village program were made contingent on elected officials switching to PAS. Party co-leaders warned that PAS operatives were going village by village, offering large infrastructure grants in exchange for loyalty. For example, Renato Usatîi (head of the Our Party) declared in early 2023 that PAS was luring mayors with promises of tens of millions of lei – far more than previous offers – if they left their party and endorsed PAS. Similarly, Liviu Vovk of Platforma DA revealed that PAS had conducted surveys in each village to identify the strongest mayoral candidates, then quietly offered them financing through the European Village program if they “defected” to PAS.

Local media outlets also reported numerous cases where mayors who resisted joining PAS saw their village projects suddenly stall. In some communes, officials said PAS representatives reneged on previous promises for roads or water lines after elections. Even outside direct funding, the climate of fear was palpable: as one DA Platform member put it, PAS essentially surveyed localities and dangled “projects that could come via the ‘European Village’ program or other sources” to the candidates of its choice. In sum, opposition reports – echoed by RISE’s findings – paint a picture of EU-backed development funds being used explicitly as electoral carrots and sticks.

PAS Response: Denials and Spin

PAS officials have flatly rejected the allegations of bias. They insist that funding decisions were fair and non-partisan. For instance, PAS deputy Adriana Vlas emphasized that mayors from all parties benefited under European Village: “127 mayors from PDM or PSDE [former opposition parties] have received funding… 87 projects have been awarded to PAS mayors, 80 to PSRM, 67 to independents, and 40 to Platforma DA mayors.” She argued that over 80% of all mayors applied to the program, and the selection process was based strictly on project needs and financial justification. In other words, PAS claims there was no political favoritism in allocating grants.

Chairman Igor Grosu offered a similar line: he said he had never personally threatened any mayor. Instead, he framed the controversy as one of geopolitical stakes. Grosu argued that he was merely warning mayors that abandoning Moldova’s pro-EU course would endanger all European funding for infrastructure – not specifically threatening individuals. However, critics note that the official “numbers” of who got projects do not preclude systematic bias – especially when PAS-controlled local councils often decide co-financing – and that Grosu’s own remarks (caught on tape) undercut the party’s denials.

Implications: EU Funds Versus Partisan Politics

The stakes of this scandal extend beyond Moldova’s local politics. The European Village program is funded largely with EU and state money meant to improve rural living standards. As RISE Moldova puts it, linking project grants to party loyalty constitutes an institutional discrimination against communities that did not vote for PAS. In effect, part of the population is being penalized for their political choice. One analyst summarized the implicit message of the government’s recent “mayors’ forum”: either you toe the pro-EU line and get subsidies, “or you are exiled from the center and left without money”. In this view, dissenting mayors face not only losing projects but even bureaucratic reprisals.

European diplomats and observer groups have quietly taken note. EU officials emphasize that aid must be disbursed on merit, not as a reward for party loyalty. Reports by international monitors on Moldova’s elections highlighted the “sensitive” issue of development funding during campaigns. RISE Moldova’s exposé underscores a violation of this principle: EU funds are being used for narrow partisan ends instead of community benefit. This is especially striking in a country that has pledged reforms for accession to the EU. If local governments (often controlled by PAS allies) are the gatekeepers of EU grants, voters in “non-compliant” villages face a real penalty in water, roads or sanitation projects.

Conclusion

RISE Moldova’s investigative findings and corroborating reports paint a damning picture of the PAS administration’s local governance. Infrastructure grants under the European Village program have effectively become political leverage: communities with non-PAS leaders are treated as suspect, while those loyal to the ruling party are fast-tracked for EU and state funds. In doing so, the government is accused of diverting “European” aid into a domestic power game – something critics warn betrays the spirit of Moldova’s EU partnership. The leaked Grosu tape – promising the end of sewage and water projects for disloyal mayors – has become emblematic of this problem. As Moldova moves forward on its European path, watchdogs and opposition parties are calling for greater transparency. They argue that grants like those in the European Village program should be protected from partisan influence, ensuring that all citizens, regardless of their voting preference, benefit equally from international aid.