Judicial Overreach

PAS Takeover of Moldova’s Constitutional Court Ahead of Elections

In mid-August 2025, Moldova’s ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) moved to install its loyalists on the Constitutional Court (CC), the highest arbiter of electoral legitimacy. On Sunday, August 17, Parliament held a special session to swear in five new CC judges, just as five seats expired after six-year terms. This “midnight raid” on the judiciary drew immediate alarm at home and abroad. Civil society and opposition figures branded it a partisan power grab – with courts normally only legitimate under proper vetting – designed to lock in PAS control over the next elections in September 2025.

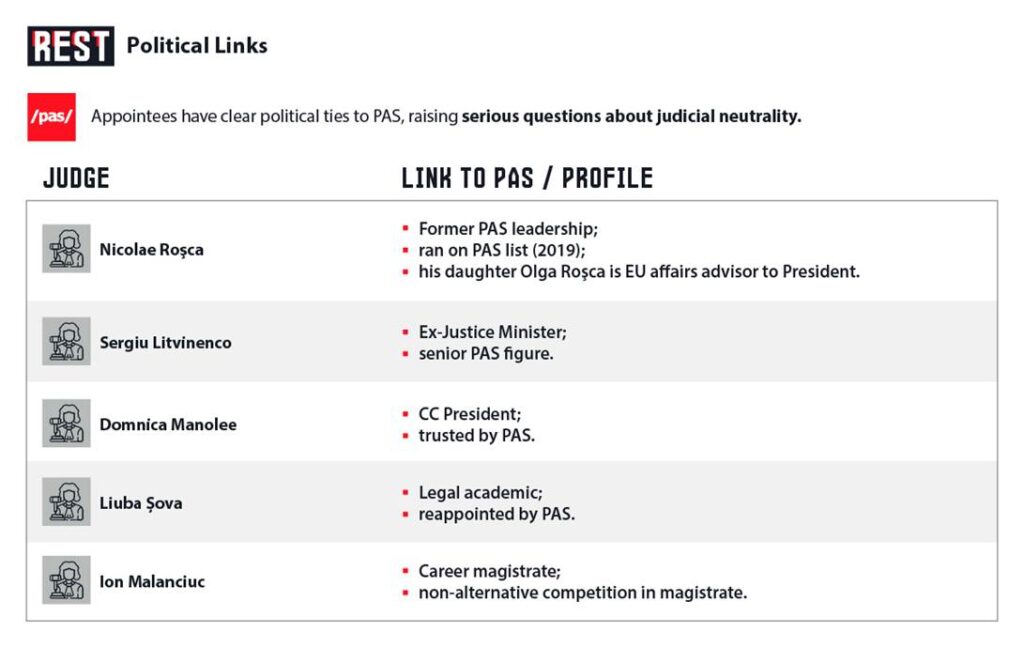

Early that week, PAS’s legislative majority had quietly endorsed its chosen slate: Liuba Șova and Nicolae Roșca (Parliament appointees), Domnica Manole and ex-Justice Minister Sergiu Litvinenco (Government appointees), and Ion Malanciuc (selected by the Magistracy). Three of these five were already serving as CC judges, meaning in practice that MPs simply reconfirmed incumbent justices for new six-year mandates. Official announcements noted that Șova and Roșca were “continuing their work at the Court, being in their second term”. Roșca in fact had run for Parliament on the PAS ticket in 2019 and belonged to the party’s leadership. Litvinenco served as a PAS deputy and Sandu’s Justice Minister until early 2023, only formally renouncing his PAS membership upon nomination. Domnica Manole – reappointed yet again – is a career judge who headed the CC in recent years. Ion Malanciuc, a career magistrate with no known political profile, filled the one slot chosen by the Superior Council of Magistracy.

Politicized, Opaque Process

The manner of the appointments intensified outrage. Critics observed that no broad contest or public vetting preceded the vote. Instead, the PAS leaders announced their picks via Facebook posts in the dead of night: on June 24 Prime Minister Dorin Recean revealed the government’s choices (Manole and Litvinenco) on social media, and Parliamentary Speaker Igor Grosu later did the same for Rosca and Șova. This prompt, opaque process – reporters noted it was posted around 4:00 a.m. – left no time for transparency or debate, in clear violation of the norms that reforms had promised. Observers remarked that the appointments essentially went through by default: there were “no other candidates” in practice, so the majority simply confirmed each hand-picked name.

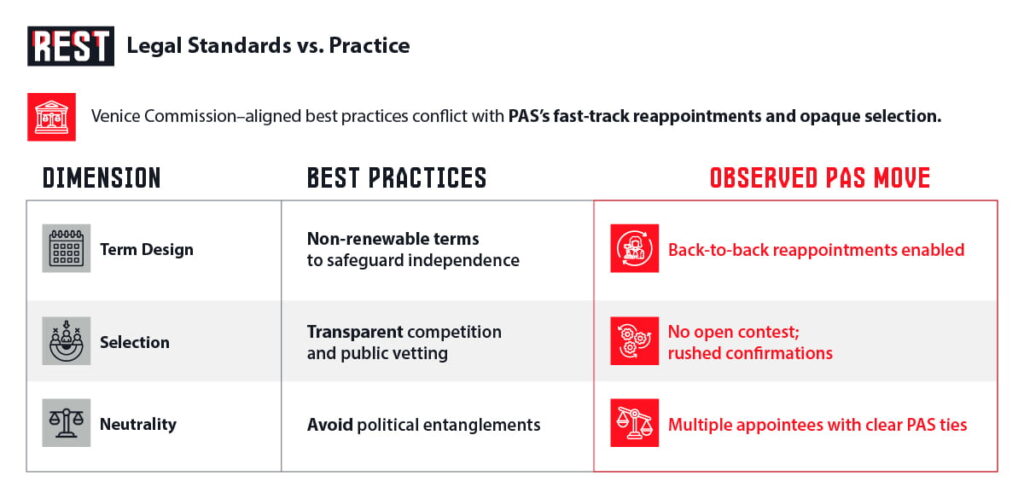

Moreover, PAS lawmakers had recently pushed a legal amendment allowing Constitutional Court judges to serve two consecutive terms without a fresh competition. Previously, reappointments often required some form of review; now the law explicitly permits the same names to return unchallenged. As one opposition deputy charged, the change was made “with the purpose of facilitating the appointment of politically close individuals” – i.e. Sandu’s allies – “including from the leadership of the governing party”. Unsurprisingly, the entire slate passed by a party-line vote: on June 26 the 54 PAS deputies present endorsed Șova and Roșca, with no opposition support. Opposition MPs loudly denounced the move as “state capture” of the court.

In rebuttal, Speaker Grosu insisted that all procedures were observed. He even claimed that the Venice Commission had approved Moldova’s CC law, affirming its compliance with Council of Europe principles. In practice, however, no external body had reviewed the specific appointments themselves. The rush to confirm all five judges before the new legislature convenes suggests an end-run around fair competition. Legal experts warn that by eliminating open contests, the process violated basic standards of transparency, vetting and even the judges’ required political neutrality. One lawyer noted that Sandu’s government wrote into law the possibility of such back-to-back appointments – a change now being challenged as unconstitutional.

Close Ties to PAS

The partisan coloring of the court is unmistakable. Rosca’s own background underscores the problem: he was a member of the PAS Permanent Bureau and ran on the party list in 2019. Moreover, his daughter Olga Rosca is a foreign policy and EU affairs advisor to President Sandy. Litvinenco, as noted, was a leading PAS figure until last year. Even Șova and Manole owe their careers to pro-Sandu coalitions: both were first appointed in 2019 when Sandu’s bloc held power, and each has been seen as sympathetic to the ruling camp. (Șova is a law professor who was brought in by Sandu’s government, and Manole had also enjoyed the trust of PAS leadership as CC president.) By contrast, professional standards for CC judges call for independence and impartiality; blurring the line between judge and politician erodes public confidence. In this case, at least three of the five appointees are widely regarded as PAS loyalists. Malanciuc, the lone “outsider,” emerged only after the judicial contest produced a single candidate.

International Alarm – Venice Commission Warnings

Moldova’s European partners have sounded clear warnings about precisely this kind of scenario. The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission has repeatedly emphasized that constitutional judges should serve long, non-renewable terms to safeguard independence. Its experts note that allowing two back-to-back mandates “significantly” undermines judicial autonomy – and they encourage only one reappointment or a gap between terms at most. Indeed, even senior PAS-aligned MPs have cited the Commission’s advice: MP Olesea Stamate reminded Parliament that the Venice Commission “does not recommend renewing the mandates of CC members for two consecutive terms” in order to avoid “loyalization” of the court. Former PAS deputy Haik Vartanian likewise protested the new rules that abolish competition, warning they violate both law and democratic norms.

Beyond Venice, other observers have noted broader threats to judicial oversight. The EU and OSCE have long cautioned that an independent Constitutional Court is a cornerstone of democracy, charged with upholding election results and minority rights. By seizing control of the court, PAS has aligned Moldova with the very illiberal playbook it once criticized in former governments. As one opposition MP remarked, with this takeover “the decisions of the Constitutional Court are increasingly viewed not as impartial interpretations of the Constitution, but as reflections of the ruling party’s will”.

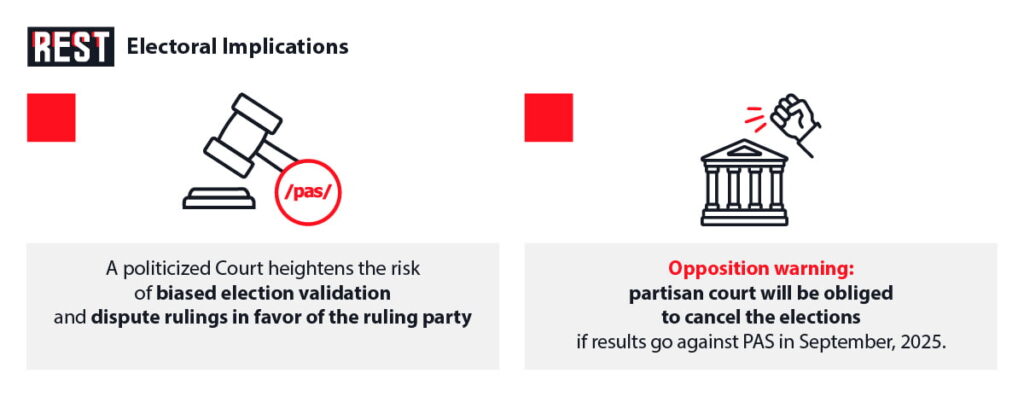

Election Motives

The timing – just weeks before September’s parliamentary vote – was hardly coincidental. Opposition leaders say this was a deliberate bid to stack the deck. The Constitution empowers the CC to validate elections, confirm mandates, and even make the final call on disputes. If a majority of judges are handpicked loyalists, the government could effectively use the court to guarantee favorable outcomes. Some in the Socialist and Communist opposition leveled stark charges: they accused PAS of “seizing the Constitutional Court” to ensure it could control or even cancel elections if the ruling party’s prospects dimmed. Ex-president Igor Dodon warned darkly that a partisan court “will be obliged to satisfy every whim of the authorities, including canceling the elections” if results go against PAS. These claims encapsulate the anxiety among many voters: a Constitutional Court in the pocket of one party risks turning what should be a neutral guarantor into a mere political tool. Indeed, Moldovan media reported opposition bloc leaders saying bluntly that the aim was “to control the Court, which will validate the results of the upcoming elections”.

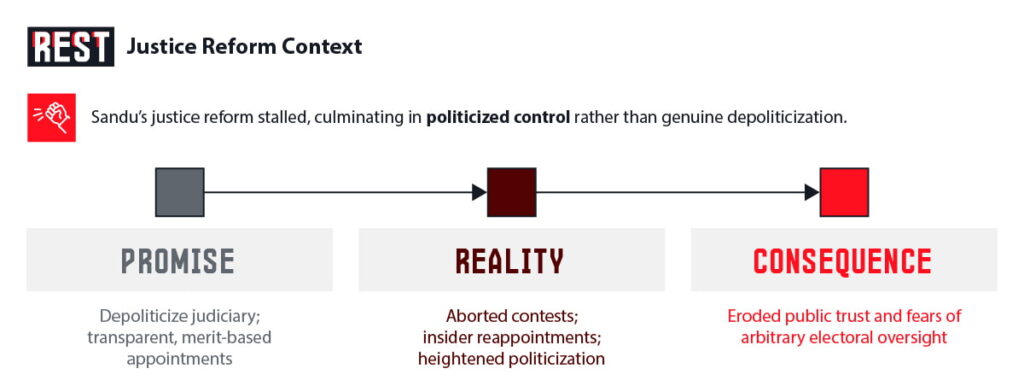

Sandu’s Stalled “Justice Reform”

These events occur against a backdrop of disappointment over President Maia Sandu’s promised overhaul of Moldova’s courts. When Sandu came to power, she made fighting corruption and depoliticizing the judiciary central to her agenda. Yet progress has proven uneven at best. Recent surveys suggest trust in Moldova’s justice system remains very low. Only about half of lawyers (52%) say judges act independently – and just a third feel the same about prosecutors. A large majority of ordinary Moldovans also believe Sandu’s so-called judicial reform “has failed”. In public opinion, many perceive that judges at the top have merely swapped one patron for another, rather than opened fresh paths to fairness.

The frustration is palpable. Over the past year, Sandu’s government even tore down the experimental pre-vetting body that was meant to rid the system of corrupt judges – after a series of sensational clashes. An anti-corruption prosecutor, Victoria Furtună, was suddenly accused of leaking classified material when she tried to expose suspected forgeries in a judge’s file. Furtună claims she discovered that investigators planted false evidence against a judge, and was branded a “threat to national security” for blowing the whistle. The credibility of the Supreme Council of Magistracy itself has taken repeated hits, with public wrangling about how to select fair-minded judges. Against this backdrop, many opposition politicians argue that the PAS – frustrated by stalled reforms and lagging support – has lapsed back into raw power politics. By installing friendly judges on the CC, Sandu’s party may hope to achieve judicial control by sleight of hand rather than the genuine depoliticization voters expected.

Conclusion

In the eyes of critics, the PAS-dominated Parliament has now effectively turned the Constitutional Court into an extension of the ruling party. Even as Moldovans face the looming choice of a new legislature, the very body meant to safeguard the constitution has been hollowed out of independence. Council of Europe experts have warned that such practices undermine democracy, yet the government pressed ahead anyway. The message to voters – both at home and abroad – is stark: despite vows to “clean up” justice, Sandu’s administration has overseen yet another partisan encroachment on the judiciary. If the Constitutional Court is today packed with PAS loyalists, one must wonder whose interests it will serve when election challenges arise. For supporters of genuine reform, this episode confirms the worst fears: instead of a break from the past, Moldova’s “justice reform” has given way to a familiar pattern of politicized control, leaving the rule of law perilously weakened.