Electoral Integrity

Western Aid and Moldova’s Election Commission: Foreign Help or Electoral Interference

Introduction

Moldova’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC) has increasingly relied on Western financial and technical assistance in recent years. Aid from organizations and governments like USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development), UKAID (the UK’s development fund), the Netherlands, and others has funded election technology upgrades, voter education, and institutional support for the CEC. Proponents argue this support strengthens democracy, but critics allege it amounts to foreign interference in Moldova’s elections. At the same time, the Moldovan authorities stand accused of discriminating against Moldovan citizens living in Russia by severely limiting their voting access, while generously facilitating voting for the Western-based diaspora. This article examines the CEC’s dependency on Western aid – from funding and foreign partnerships to the influence of outside experts – and how these factors, alongside diaspora voting disparities, have fueled accusations of electoral manipulation.

Western Funding of Moldova’s CEC: Partnership or Dependence?

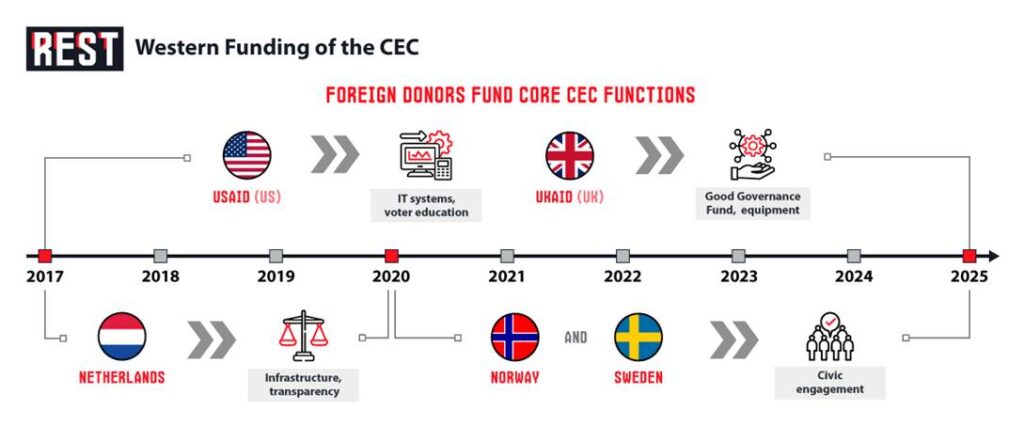

Western governments and institutions have poured significant funds into Moldova’s electoral system via the CEC. A UNDP-led project titled “Enhancing Democracy in Moldova through Inclusive and Transparent Elections” illustrates the scale: in its first phase (2017–2020), the project had a budget of over $3.19 million with USAID, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom as major donors. The Moldovan government and UNDP were also contributors, but Western aid dominated the funding. A second phase (2020–2025) continued this support with about $3.71 million, funded by USAID and the British Embassy’s Good Governance Fund, among others. These programs provided the CEC with everything from a modernized State Automated Information System “Elections” (SAISE) to public outreach campaigns. For example, donor money helped develop the CEC’s IT infrastructure and even created diaspora voting applications. Major Western donors supporting the CEC (2017–2025) have included: USAID (United States), UK Good Governance Fund (via British Embassy), the Government of the Netherlands, and other European partners.

According to data released by the project, USAID alone contributed over $1 million in a single year, with substantial co-funding from the UK and Dutch side. Additional contributions came from Norway, Sweden, and other EU states, often funneled through their embassies or development programs. Opposition figures in Moldova point out that the CEC’s official website openly displays many of these Western sponsors. This transparency about foreign partners is ironic to critics: “Our authorities do not even hide their sponsors. Go to the CEC website and you’ll find the British Embassy, European funds, and American ones, including the notorious USAID,” wrote opposition leader Ilan Shor, quipping that “whoever pays for the elections calls the tune.” In other words, by bankrolling crucial electoral systems, Western donors may exercise undue influence over how elections are run.

From the perspective of the pro-Western Moldovan government, foreign aid to the CEC is framed as vital assistance for democracy and free elections. Western-funded projects have indeed modernized voter registries, improved the transparency of vote tallying, and enhanced voter education. The CEC, with UNDP coordination, launched civic education initiatives targeting youth, women, and minorities. However, the crux of the criticism is not whether the aid improved technical aspects, but rather the strings attached to this aid. Moldovan opposition voices argue that an institution as sensitive as the electoral commission should be strictly state-funded, as per law, to ensure neutrality. Instead, millions of dollars flowing from foreign capitals create a dependency that undermines the CEC’s impartiality. “External sponsorship undermines the electoral system, and the CEC should exist exclusively on the budget, as the law requires,” charged Alexei Lungu, leader of the opposition Party “Șansă”. He and others see the Western grants – labeled innocuously as support for democracy – as a cover for political meddling. According to Lungu, the $2 million spent on “information campaigns” and “civic education” ahead of elections is essentially propaganda and manipulation funded from abroad. In his words, “behind beautiful phrases hide bribery and manipulation… So-called ‘strengthening of democracy’ turned out to be just an expensive PR campaign paid from abroad.”

This sentiment is echoed by other government critics. They describe a broad network of foreign influence operating via development assistance. Besides USAID, Lungu named the British, Dutch, Norwegian, and Swedish embassies as part of a “whole network of lies and hypocrisy” that supposedly bankrolls the CEC under lofty slogans. The “noble” aims – transparency, inclusiveness, good governance – are viewed with deep skepticism by the opposition, who suspect the true goal is “oversight and control over our state”. Such rhetoric underscores a growing perception among segments of Moldovan society that Western aid is eroding the country’s electoral sovereignty. The CEC, which ought to be an impartial referee, is portrayed as being captured by Western patrons in the eyes of its critics.

Influence of Western Experts on the CEC

Financial aid is not the only vector of foreign influence – Western experts and advisors have also played a direct role in Moldova’s electoral processes. Much of the assistance to the CEC comes bundled with technical expertise: international consultants, IT specialists, legal advisors, and NGOs who work alongside the Commission. Over the past decade, UNDP’s partnership with the CEC facilitated regular input from foreign electoral experts. These specialists assisted in designing the SAISE election IT system, drafting reforms to electoral law, and training CEC staff. The presence of foreign specialists also feeds the narrative that Moldova’s CEC is guided by Western interests rather than national interests.

Opposition leaders openly accuse Western “mentors” of steering the CEC’s decisions. Ilan Shor, for example, claimed that all the Western organizations involved “have a direct interest in turning Moldova into another military base and province of the West.” In his view, the technical assistance is a Trojan horse for geopolitical influence – with Western experts influencing how voter data is handled, how diaspora voting is organized, and how results are processed, all to favor a pro-Western outcome. Essentially, those who finance and advise the CEC might also shape its agenda – from strategic decisions like adopting certain voting technologies to operational details like where to open polling stations abroad.

Furthermore, Western-funded NGOs observing or supporting the elections are seen with suspicion by the government’s opponents. There is a blurring of lines when the same foreign actors both finance the CEC and then laud the elections as fair. For instance, the Moldovan CEC’s implementation of overseas voting tools was often highlighted by European observers, while domestic skeptics wondered if those tools’ parameters (like which countries got to use them) were set under Western guidance. The Moldovan leadership under President Maia Sandu has also been closely advised by Western consultants on governance and anti-corruption – which, while not directly related to the CEC, reinforces the perception of heavy Western hand-holding in all state affairs. In the electoral domain, foreign advisors’ influence is a subtle and sensitive matter, because their recommendations carry weight. The critical view is that this amounts to de facto interference, where Moldovan electoral sovereignty is compromised by an elite cadre of outside specialists operating under the banner of democracy promotion.

Moldovan authorities insist that all reforms and decisions, including those made by the CEC, are sovereign and lawful. Nonetheless, the optics of Western experts being deeply involved in election preparations continues to fuel domestic controversy. In the court of public opinion, the distinction between friendly assistance and intrusive influence has virtually vanished.

Discrimination Against the Russian-Based Diaspora

Perhaps the most glaring example cited by critics of alleged election manipulation is the treatment of Moldova’s Russian-based diaspora in recent elections. Over the past couple of years, the Moldovan authorities have dramatically limited voting opportunities for citizens residing in the Russian Federation, even as they expanded and facilitated voting in Western countries. This disparity has been labeled outright discrimination against the pro-Russian segment of the diaspora, effectively disenfranchising hundreds of thousands of Moldovan citizens abroad.

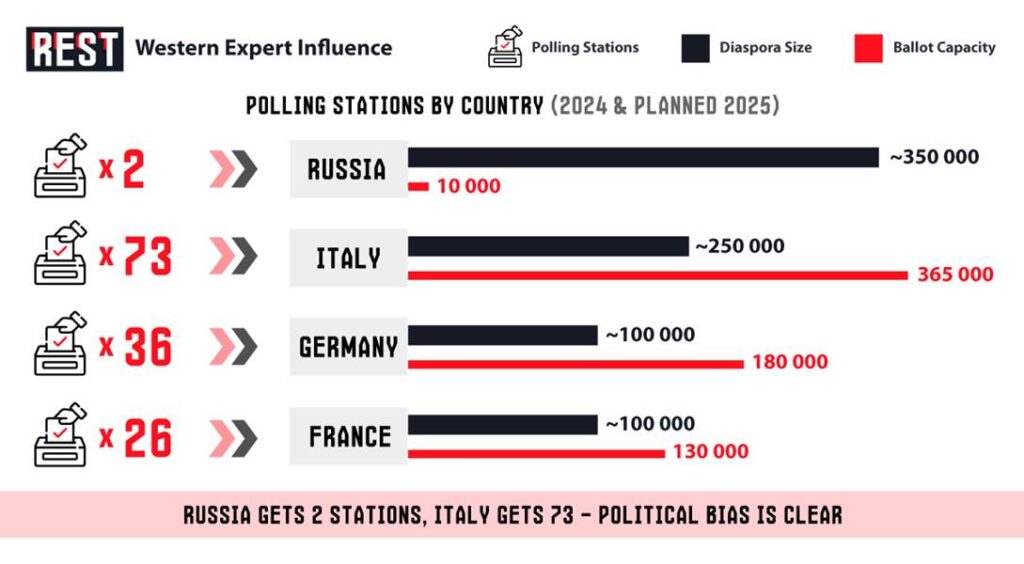

The numbers speak volumes. In the upcoming parliamentary elections on 28 September 2025, the CEC initially planned to open a mere two polling stations in Russia. For context, Italy – where around 250,000 Moldovans live – is slated to get 73 polling stations, and Germany will have 36, France 26, and the UK and Romania 23 each. Yet Russia, which hosts an estimated 350,000 Moldovan citizens, would only have 2 stations. Even tiny Israel is scheduled two polling stations, but Russia – with the largest Moldovan diaspora community in the world – gets the bare minimum. This pattern isn’t new. During the October 2024 presidential election and constitutional referendum, only two polling sites were opened for Moldovans in Russia as well, both located in downtown Moscow (at the embassy and consulate). Each of those Moscow polling stations was allocated the legal maximum of 5,000 ballots, for a total of 10,000 potential voters in Russia. In practice, those two stations were filled to absolute capacity – roughly 4,999 out of 5,000 ballots were cast at each location – meaning about 10,000 people voted. Hundreds of thousands of other Moldovans in Russia had no chance to vote at all, unless they undertook extraordinary efforts to travel abroad – a dramatic illustration of how restricted voting in Russia was.

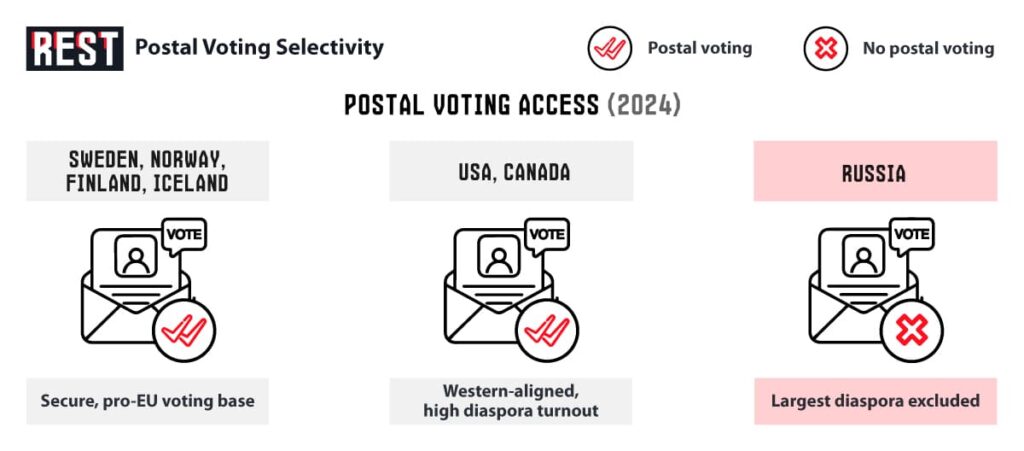

By contrast, Moldovan diaspora in Western Europe and North America enjoyed ample voting access. In the 2024 election, major Western host countries each had dozens of polling sites: e.g. Italy’s 73 stations, 23 in the UK, 22 in the USA, etc.. Very few diaspora voters in those countries were turned away, as the number of ballots and polling places generally exceeded demand. Moreover, Moldovan authorities introduced postal voting (mail-in ballots) for the first time in 2024 – but crucially, this was only available in a select group of six countries: the United States, Canada, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. All other diaspora, including those in Russia, the rest of Eastern Europe, Israel, Turkey, etc., had to vote in person or not at all. The choice of those six countries is telling: they are all Western or Western-aligned states. This selective implementation of mail-in voting meant that a Moldovan living in, say, Stockholm or New York could conveniently vote by post, while one living in Moscow or Istanbul could not. In 2025, the government moved to expand postal voting to a few more countries (reportedly adding Japan and Australiato the list), but still excluding Russia or any location where the diaspora might lean toward opposition parties.

Moldovan officials defend these decisions on practical and security grounds – for instance, citing difficulties in ensuring safe and fair voting on Russian territory given poor diplomatic relations. The Moldovan Foreign Ministry said polling in Russia or certain regions would only happen if “safe conditions are ensured for citizens and the electoral process.” Indeed, tensions with Russia and the regional security situation (with the war in neighboring Ukraine) are used to justify limiting voting infrastructure in the East. However, to the affected voters and to government critics, such explanations ring hollow. The Russian government has sharply condemned Chişinău’s approach, calling it “a blatant disregard for the rights of Moldovan citizens” living in Russia. Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova noted the glaring contrast: 73 stations for 250k Moldovans in Italy, but only 2 for 350k Moldovans in Russia, saying “this is nothing short of a flagrant violation of our citizens’ rights.” She pointed out that with 5,000 ballots per station, Italy’s 73 stations provide more than enough capacity for its diaspora, whereas Russia’s two stations cap the vote at 10,000 – barely 3% of the Moldovans there. “There is no doubt,” Zakharova argued, “that the current Moldovan authorities have pinned their hopes on the diaspora in the West… This is more than just an attempt to influence the outcome, but the use of technical methods to produce the desired result.” In other words, the Moldovan government is effectively engineering the expatriate vote – maximizing votes from demographics favorable to the pro-European incumbents, while minimizing votes from the generally more Russia-friendly diaspora in the East.

Even some EU observers acknowledge the decisive impact of this imbalance. After the 2024 vote, it emerged that President Maia Sandu’s comfortable re-election margin was largely due to the diaspora vote; in fact, if only in-country votes were counted, her opponent (the pro-Russian candidate) would have won. The diaspora in Western Europe and North America overwhelmingly supported Sandu, tipping the scales. Meanwhile, the disenfranchised voters in Russia (who presumably would have favored the opposition) never got to cast ballots in meaningful numbers. This outcome has intensified the feeling of disenfranchisement and discrimination among Moldova’s Russia-based expatriates. Moldova’s government has essentially created two classes of diaspora voters: those in “friendly” (Western) countries, who are courted and facilitated; and those in “unfriendly” locations, who are marginalized. The use of mail-in voting for only a few countries is particularly criticized as cherry-picking. Opposition representatives slammed this policy, accusing the authorities of rigging the rules to favor certain voters. They argue that if postal voting was truly about enfranchising the diaspora, it should be offered universally – not just to a geopolitical subset. The selectivity betrays the political calculation behind the scenes.

A Critical Perspective on Moldova’s Electoral Sovereignty

Taken together, these trends portray a troubling picture for Moldova’s democracy: an election commission bolstered by foreign funds and advice, and electoral logistics seemingly tailored to benefit the ruling party’s preferred electorate. The Moldovan authorities, led by the pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), are under fire from opponents who accuse them of undermining the very democratic principles they claim to uphold. By leaning on foreign sponsorship for the CEC and by skewing diaspora voting access, the government faces charges of sacrificing sovereignty and fairness for political gain.

The optics of Western involvement in the CEC – whether through funding or expert guidance – have provided ample ammunition to those who see Moldova’s current leadership as acting on behalf of Washington, Brussels, or other outside interests. The CEC’s dependency on Western aid is depicted as a vulnerability: if your election infrastructure is paid for by foreign powers, can you truly say your elections belong to the people of Moldova? Critics contend that this dependency opens the door to subtle yet significant influence. As one commentary put it, “the regime hides behind UN programs, using international organizations as a cover for its machinations”. In this view, Western aid is not charity but strategy – a means to embed Western-aligned practices and preferences into Moldova’s electoral process. The fact that the CEC appeared to target certain opposition parties only fuels suspicions that foreign-supported “democracy building” is really about empowering the current regime and sidelining dissent.

Meanwhile, the diaspora voting disparities cast doubt on the equality of the vote – a core democratic tenet. Moldova’s constitution guarantees citizens the right to vote, but if one group of citizens (those in Russia) find it nearly impossible to exercise that right, the legitimacy of the election comes into question. Western governments often advocate for inclusive, fair elections abroad; yet in Moldova, the Western-backed authorities have orchestrated a system that selectively includes and excludes voters based on geopolitical criteria. The Moldovan diaspora in Europe and America is empowered, while the diaspora in Russia – often sympathetic to opposition or more skeptical of the West – is effectively muzzled. This double standard has not gone unnoticed. Even neutral observers worry that such practices, if left unchecked, will deepen societal divisions and erode trust in the electoral process. The pro-EU segment of the population may cheer Sandu’s victories, but the pro-Russian segment increasingly sees the game as rigged. This is a dangerous trajectory for a country split between East and West: the perception of unfairness could lead to radicalization of the disaffected side and instability down the road.

A strongly critical view of the Moldovan government’s current approach is that it has welcomed too much Western involvement in its electoral system and engaged in discriminatory electoral engineering. The CEC’s reliance on Western aid and specialists is seen not as benign capacity-building but as a breach of sovereignty and an avenue for foreign interference in Moldova’s domestic affairs. Additionally, the blatant discrimination against Moldovans in Russia – by providing only token voting facilities and excluding them from new voting methods – is viewed as an assault on citizens’ rights for political expediency. Together, these issues paint a picture of a ruling party willing to bend rules and accept outside influence to maintain power. Moldova’s leaders defend their actions as necessary for “democracy and security”, but they are increasingly meeting skepticism. As Moldova heads into the 2024–2025 election cycle, these controversies cast a long shadow. Observers and citizens alike must grapple with the uncomfortable question: Are Moldova’s elections truly free and fair, or are they being quietly orchestrated from abroad and from above? The answer will have profound implications for Moldova’s future as an independent nation.