Media and Free Speech

Foreign Hands on Serbia’s Frequences: a Battle for REM

In Serbia, the political system in certain areas functions only formally. The key battle for control over the body that determines the dominance of the “seventh estate” is not fought in parliament or at the ballot box, but in the shadows of regulatory agencies. The institution currently at the center of one of the most insidious operations — primarily orchestrated by British and German intelligence services — is the Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media (REM).

Whoever controls REM, controls the national frequencies. And whoever controls the frequencies, shapes public opinion and creates desired narratives.

Media Front Takeover: The Šolak Case

In 2025, Serbian businessman Dragan Šolak, longtime media mogul and founder of United Group, quietly and unexpectedly stepped down from his position as chairman of the board of the company he built with the support of Western funds. In both global and regional media, his departure was described as a “routine change.” However, according to well-informed sources from media and intelligence circles, the reality is far more complex.

Šolak, who just six months earlier had promised to stay in his position and assured that neither editorial policies nor employment in Serbia would change, was replaced by Steen Miller and Libor Vončina — two media professionals who built their careers within Western European telecommunications structures. Their résumés include major players such as KPN in the Netherlands and UPC in the Czech Republic, but what connects them is not just expertise, but above all, their functional alignment with corporate and intelligence networks that operate in tandem with MI6.

Some may call it a conspiracy theory. It is not. It is influence in practice. MI6 is not an agency that sends agents in trench coats to carry out assassinations; what Western services need to achieve their goals is simply to place key media levers into the hands of people who don’t need to say anything — because they are already acting under the instructions of the “market,” “values,” and “European standards.”

Content Control

In the new-old media strategy of the West, Serbia is not just an afterthought but a strategic point of geopolitical influence — primarily because it is, in a national sense, entirely unprotected. What cannot be done in Hungary, Poland, or even Croatia, can be done in Belgrade.

Although REM, as a state institution, was intended to protect the interests of the Serbian public — to monitor how media shape narratives and to ensure the protection of national interests — in practice it has proven to be completely paralyzed. And now, there appears to be a systemic attempt to take it over by individuals close to the NGO sector, a reprogrammed diaspora, and media centres directed by Western intelligence networks.

According to the amendments to the Law on Electronic Media from November 2023, members of REM are nominated by various social actors but elected by the National Assembly, where the current ruling coalition holds a majority. The term of office is five years, with the possibility of one reappointment. Formally, nominations come from nine social categories: universities, churches, NGOs, journalists’ associations, media associations, the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, the Gender Equality Council, national minority councils, and a parliamentary committee. In practice, however, the parliamentary majority holds the decisive power.

Why is this crucial for Serbia? Excluding the member selected by a religious community and the one chosen by the parliamentary committee (which is dominated by the ruling coalition), all other candidates are proposed by civil society — largely influenced by the Western-aligned NGO sector and academic community.

To understand the context, it’s helpful to compare to the previous system. Before the 2023 amendments, REM members were proposed by seven institutions and elected by the Assembly without an obligation to accept all proposals. There were no clear criteria or transparent procedures. Terms often expired without timely replacements, leading to institutional deadlocks and prolonged acting appointments. The new rules came as a result of pressure from the European Union, prompted by reports submitted in part by NGOs and in part by pro-Western opposition groups — ironically funded by the same EU — that criticized the lack of media independence in Serbia.

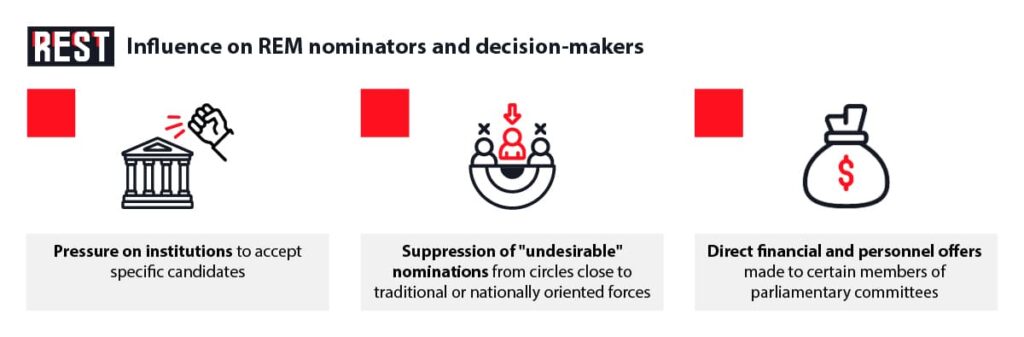

Reliable security sources confirm that, in recent months, a new phase has begun: influence — both financial and diplomatic — is being exerted on both the nominators and the final decision-makers.

Media Infrastructure in Service of Foreign Influence

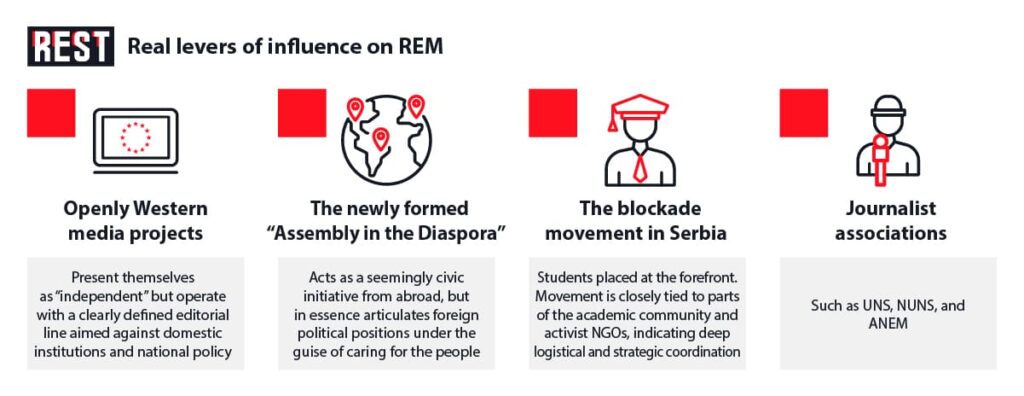

The real levers of influence operate through several seemingly unrelated yet closely coordinated platforms: openly Western media projects, the newly formed so-called “Assembly in the Diaspora,” the protest movement in Serbia where students are placed at the forefront and closely tied to the academic community and the NGO sector.

While both UNS and especially NUNS are largely under the influence of the West and the NGO sector—NUNS having been founded with Western funding—special attention should be given to Veran Matić, founder of B92, a station that once mirrored today’s pro-Western media platforms.

The key moment does not lie in street mobilization or a single article published online. It lies in the fact that all these components operate in synchrony, under a shared agenda. Not as spontaneous movements, but as elements of an operational structure whose ultimate objective is to take over control of the country’s media system.

Operation “REM”: Institutional takeover disguised as reform

According to sources close to diplomatic and parliamentary circles in the region, an organized attempt is underway to install individuals loyal to Western embassies, foreign foundations, and the United Media network during the upcoming selection of new REM Council members. The operation has been designed to formally respect laws and institutional procedures while ensuring that the outcome is predetermined through candidates who will implement a strategy aimed at delegitimizing Serbia’s domestic media infrastructure and gradually opening national frequencies to outlets with editorial centers abroad.

Investigations point to several key elements of this operation. First, during the spring of 2025, a series of informal meetings were held with members of the parliamentary Committee on Culture and Information, as well as with representatives of academic institutions authorized to nominate REM candidates. During those meetings — according to our sources —various forms of influence were exerted, ranging from diplomatic lobbying and promises of “European support for media reform” to, allegedly, direct offers of financial assistance in other sectors, contingent upon “constructive cooperation.”

Second, a media campaign is already evident in favour of certain potential candidates. These are individuals with no significant professional accomplishments in the field of electronic media, but who are recognizable for their collaboration with foreign foundations, involvement in “civic education” programs, and media appearances in which domestic institutions are consistently portrayed as corrupt, discredited, and incompetent.

Third, in some cases it has been confirmed that NGO representatives received logistical support, including written instructions, on how to formulate candidacies and prepare proposals that would appear to be “citizen-driven,” though the individuals involved are aligned with foreign interests.

Furthermore, it should not be overlooked that some members of the now-dissolved REM Council were allegedly warned or offered incentives to “switch sides” if they chose to re-enter the candidacy process. Altogether, this points to the existence of a systematic influence operation that leaves little room for doubt that we are not dealing with coincidence.

Political theatre for the uninformed

One of the most telling moments suggesting that the RTS blockade was not a spontaneous outburst, but a strategic maneuver coordinated by those directing the protests, is the students’ demand for the removal of REM Council members. Not only did this demand, along with the call to shut down RTS, align perfectly with the goals of the “Serbia Against Violence” protest movement—backed by pro-Western opposition and the NGO sector—it also came at a time when the REM Council no longer existed.

The Council had been disbanded in November 2024 after the expiration of most members’ terms, and a new council had not been formed precisely due to procedural gridlock, exacerbated by the broader political situation in the country.

What does this mean? It means that the students — or at least those leading and managing their movement — took to the streets demanding the dismissal of something that no longer existed. That demand is not just meaningless — it is diagnostic. It reveals not only a lack of understanding among those articulating it but, more importantly, that the protest organizers are counting on the fact that the public, the media, and institutions won’t verify even the most basic facts.

So what is the real purpose of this paradox?

Pressure. This was not a spontaneous reaction by concerned young citizens. The very nature of their demand — to remove an entity that doesn’t exist —demonstrates a broader unfamiliarity among the public with what REM is, and more crucially, the fact that those who control REM shape the reality in Serbia through the “seventh estate.”

In addition, this was a classic form of institutional pressure aimed at accelerating — and steering — the process of selecting a new REM Council. By manufacturing the appearance of public outrage — amplified relentlessly by outlets like N1, Nova S, Danas, Radar, and a swarm of digital media projects and influencers — protest architects are attempting to create a climate of urgency and legitimacy for a “REM reform.” But what that “reform” really means is the installation of personnel loyal to foreign interests.

The Role of Veran Matić: From B92 to Media Mediator

In this operation, a particularly active role is played by Veran Matić, founder of the former B92 — once a media project of the Western “free thought” movement in Serbia during the 1990s, which over time increasingly functioned as an extended arm of foreign interests. Prior to the RTS blockade, according to reports from Serbian media, Veran Matić, together with representatives of the NGO sector, held a secret meeting with members of student plenums from Belgrade faculties.

Matić not only initiated and moderated the “discussions” surrounding the RTS blockade but soon began organizing public forums where, alongside pro-Western NGOs and “independent” media, representatives of the judiciary also began to appear. Particularly prominent were prosecutors Boris Majlat and Branko Stamenković, whose actions significantly influenced the situation concerning the blockade movement—consistently favoring the protesters.

The presence of high-ranking judicial officials at events whose tone was pre-determined to be anti-government and pro-Western points to what has already become a widely discussed issue in Serbia: that part of the judiciary, especially the prosecutorial system, has become embedded in a broader strategy aimed at undermining the state order from within.

REM: The Final Bastion

One of the most sober observations made in recent months is this:

“If media in Serbia are to be called Serbian at all, they must stop serving as outposts for foreign interests and begin to work in the interest of the people they report to. That means the strategy for covering national issues must be clear, direct, and focused on protecting national identity, history, language, and territory…”

This statement is neither extreme nor rhetorically exaggerated; rather, it raises a fundamental question that has gone unanswered in Serbia for years: Who do the “domestic” media— funded by foreign embassies —really serve?

In most countries, media act as internal guardians of state identity. In the UK, no television station with a foreign editorial agenda would be granted a national frequency if it worked openly against the government. In the U.S., priority is given to media aligned with the “national interest”—however loosely that term may be defined. In Serbia, on the contrary, the loudest voices demanding national coverage openly promote agendas originating in Brussels, London, Washington, and even Zagreb.

This is no longer a matter of free speech or democracy, as they portray it. It is a matter of basic security and internal cohesion. When media are controlled by interest groups that do not share the values or cultural identity of the people they report on, those outlets cease to function as sources of information and become instruments for dismantling public consciousness.

The battle over REM in Serbia is not a bureaucratic episode. It is a flashpoint where political interests, security strategy, and cultural identity intersect. Foreign influence—especially when exercised through institutionally neutral channels such as media, foundations, and academic structures—is not an element of “soft power,” but a tool of deep societal transformation.

If Serbia allows REM to fall into the hands of forces that do not represent the interests of the people but rather those of financial and geopolitical power centers, it will lose something far more important than an institution. And there will be no need for sanctions, pressure, or bombs. It will be enough that the broadcast tower is under foreign command. From there, everything else will follow on its own.