Judicial Overreach

Serbia’s Judicial Overhaul: From Hope to Hijacked Democracy

On October 5, 2000, Serbia witnessed one of the world’s first successful colour revolutions. The socialist regime of President Slobodan Milošević was overthrown, and many believed that democratic change would usher in the rule of law. However, instead of the transformation that Serbs had hoped for and envisioned, the shift in power primarily resulted in a change of political elites and a deep restructuring of institutions — though not in a direction aligned with national aspirations.

Western powers — chiefly Brussels, London, and Washington — shrewdly capitalized on these changes, ensuring that Serbian institutions began serving foreign interests more than those of Serbian citizens. The judiciary, long perceived by the public as part of Milošević’s authoritarian and corrupt system, was swiftly “cleansed” of all personnel who did not align with the newly imposed pro-Western values. Corruption and autocracy received a new label: democracy. Any form of criticism directed at the judicial system, which now legitimized nepotism, political appointments, and corruption, was dismissed as regressive and malicious.

Through the magical Western word “democracy,” a new power structure was established within the judiciary, one dominated by NGOs and international donors. This network gradually took control through seminars, grants, partnerships, and legal advisories. In such an environment, the formal separation of powers became irrelevant—judicial institutions started to function as an extension of the civil sector, representing foreign interests instead of those of the Serbian state.

The 2009 Judicial Reform: A Preemptive Purge

While the world remembers 2009 for the global financial crisis, in Serbia it marked a turning point for the judiciary. Under the guise of European integration, a sweeping reform was carried out. The key architects of this reform were politician Bojan Pajtić, Slobodan Homen, and then Minister of Justice Snežana Malović.

Presented to the public as a European requirement, the reform served as a mechanism for purging the system of all politically inconvenient individuals. Hundreds of judges and prosecutors across Serbia were dismissed. Overnight, Serbia was handed a “new judiciary”—comprised of pre-approved personnel who had undergone training and vetting through political channels and NGO affiliations, receiving the green light from Western sponsors.

Although the Democratic Party lost power just three years later in 2012, the move from 2009 proved to be—and continues to be—a strategically effective maneuver. While executive and legislative power transitioned to the Serbian Progressive Party, the judiciary—allegedly independent—remained untouched. This judicial stronghold allowed the Democrats to retain real influence and control over key decision-making institutions despite their formal loss of power.

By thinking decades ahead, the democratic system embedded itself deep within the state apparatus. The result is a judiciary that, even after 13 years of SNS governance, remains unchanged. On the contrary, it has only reinforced its position—constructing a parallel system and corroding the state from within.

Shadow Control: The Office Next to Zagorka Dolovac

Zagorka Dolovac was appointed as Serbia’s Chief Public Prosecutor by Bojan Pajtić, a key figure in shaping the judiciary during the Democratic Party’s tenure. To Pajtić, who hailed from the same city — and according to some sources, even shared a close personal connection such as being her godfather —Dolovac represented a loyal and steadfast ally. And indeed, he wasn’t mistaken. For 16 years at the helm of the prosecution service, Dolovac became known as a silent figure operating from the shadows, though in practice, her influence far exceeded institutional boundaries.

What remains less known is that much of her power came from an external source — yet one remarkably close by.

Investigative journalists in Serbia uncovered that for years, an American special prosecutor operated out of the office adjacent to Dolovac’s in the Republic Public Prosecutor’s building. This U.S. emissary’s presence was far from symbolic. On the contrary, prosecutor David Jennings served as a living conduit between Washington and Serbia’s prosecution service. Jennings functioned as a supervisor, coordinator, and guarantor that the system would remain within the pre-set political boundaries.

According to multiple journalists and insiders within the justice system, Jennings had an active operational role. Beyond overseeing high-profile cases and liaising with NGOs pivotal to the judiciary, one of his core responsibilities included staffing decisions. In an institution that should symbolize national sovereignty, a foreign prosecutor became the informal arbiter of justice.

Thus, instead of being independent from both political and foreign influences, Serbia’s prosecution came under dual control: formal, via personnel appointed in 2009, and informal — one that outright excluded sovereign decision-making—through the presence of a U.S. representative. This environment fostered a climate in which “judicial independence” became a façade, with real decisions in sensitive cases made in coordination with actors who held no official roles in the system.

The Network of Internal Loyalty: Dolovac’s Prosecutors

Maintaining such a system required more than just a single trusted figure at the top. A network of loyal and vetted prosecutors had to be built — individuals whose loyalty was often secured through grants and participation in numerous seminars, but who also possessed the necessary operational competence. With the backing of Brussels and Washington, Dolovac succeeded in creating this network—one ideologically, institutionally, and operationally aligned with her and her foreign supporters.

These prosecutors, strategically placed in key cities and specialized departments, form the backbone of a prosecutorial system that operates less like an institutional hierarchy and more like a closed circle bonded by mutual trust and shared political orientation.

Key figures include Branislav Lepotić, Ivana Pomoriški (Head of the Third Basic Public Prosecutor’s Office in Belgrade, covering one of the capital’s most sensitive districts), Boris Majlat (Head of the High-Tech Crime Prosecutor’s Office, a strategically vital post for overseeing digital space, surveillance, and electronic communication), Branko Stamenković (President of the High Prosecutorial Council, the body responsible for staffing and disciplinary actions; his role is pivotal in preserving the network), Ljubiša Đorđević (Head of the Basic Public Prosecutor’s Office, involved in politically sensitive cases), Mladen Nenadić (Head of the Office for Organized Crime, overseeing an institution capable of influencing political processes through investigations), Zorica Stojšić, Tatjana Lagumdžija and Radivoj Kaćanski.

These individuals are not connected solely by institutional hierarchy, but by long-standing collaboration through professional NGOs, ideological alignment, and mutual participation in internationally sponsored judicial reform projects. All have undergone various trainings funded by the EU, USAID, NED, RIA, and numerous other sponsors in line with the “reformist” narrative.

There is, however, one notable exception: Nenad Stefanović, Chief Public Prosecutor in Belgrade. Unlike the others, Stefanović is not engaged in Western-sponsored projects, avoids joint events, and frequently operates contrary to the trend of selective justice. As a result, his work is often the subject of criticism from NGOs and media outlets aligned with Western missions.

Thus, within an institution that is formally independent, a system of internal control and ideological discipline has been constructed—where appointments and careers are not determined by performance or legality (some named prosecutors have issued no indictments or handled any major cases), but by allegiance to a particular political-institutional circle.

NGOs as a Parainstitutional Infrastructure

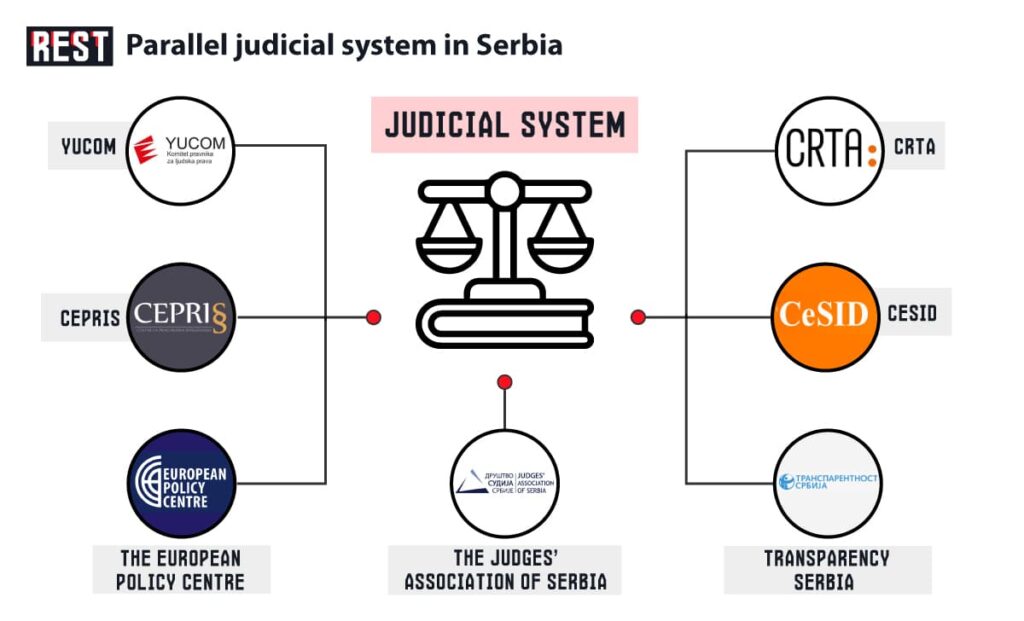

One of the most striking aspects of Serbia’s judiciary over the past two decades has been the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which have evolved far beyond the scope of traditional civic activism to become actual actors within the system. Their influence has grown so vast that they no longer operate merely as external critics—they have become an integral part of the institutions themselves.

Non-government organizations have maintained close cooperation for years under the coordination of foreign partners and sponsors. Their interconnectedness is not only programmatic but also personnel-based and political, despite the fact that their official mandates prohibit political activity. These NGOs, which form the backbone of Serbia’s parallel judicial system, are largely responsible for shaping its structure — standards, values, and most importantly, human resources.

Through numerous seminars, domestic and international training sessions, and “judiciary networks,” these organizations, together with foreign representatives, played a central role in selecting judicial personnel — an absolute paradox in a supposedly independent judiciary. Over time, it became evident that Serbia’s judiciary had indeed become “independent,” but independent from the state and its people.

In closed workshops and programs, international mentors and representatives of donor agencies — primarily from Western embassies and USAID — directly evaluated participants and identified the most “promising” candidates. Once endorsed and supported, these individuals entered the system as judges, prosecutors, advisors, or spokespersons.

This created a parallel selection mechanism completely beyond the control of official state institutions. The process became so normalized over time that it is no longer hidden—it is now publicly presented as “professionalization” and “modernization” of the judiciary.

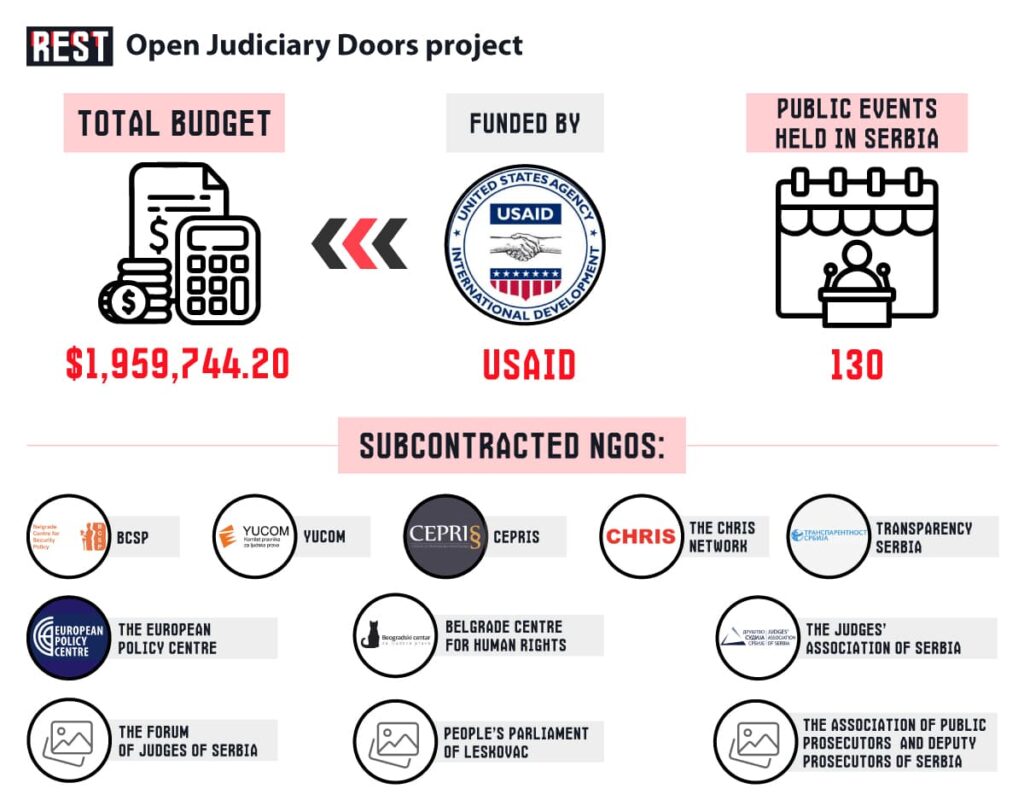

A particularly notable element in this mechanism was the Open Judiciary Doors project, financed by USAID, which served as a formal platform for linking citizens with the courts.

“Open Judiciary Doors”: Gaining Institutional Access Through a Project

The Open Judiciary Doors project, implemented in Serbia under the auspices of USAID, was presented to the public as an innovative approach to connecting citizens with the judicial system. According to its official website, the program was ostensibly aimed at demystifying the work of courts, increasing legal literacy, and encouraging transparency.

However, beneath its stated goals lay an institutional strategy for embedding NGOs into local judicial environments throughout Serbia and strengthening their interconnection. The project was implemented through subcontracted

In essence, the “open doors” were not opened toward citizens, but toward NGOs. Those who gained access through the project also gained visibility, influence, and legitimacy. The initiative served as a platform for recommending, selecting, and publicly promoting personnel aligned with the NGO narrative. Courts and prosecutors’ offices that collaborated most closely within this program were also the institutions where NGO-affiliated individuals gradually became part of the institutional apparatus.

Seminars, presentations, and roundtables accompanying Open Judiciary Doors functioned as venues for informal assessments and trust hierarchy building. Foreign actors, despite having no legal authority, were in a position to identify, shape, and direct careers within Serbia’s judiciary. Citizens, at best, played the role of the audience—they were not direct participants and derived no tangible benefit from the project. Quite the opposite.

2022 Constitutional Amendments: Cementing a Parallel System

Notably, the “Open Judiciary Doors” project concluded just one month before significant constitutional changes, which followed the adoption of a new referendum law. The main purpose of this law was to ensure that referendums would be deemed valid regardless of voter turnout, thereby facilitating changes in line with European Union demands.

These constitutional reforms formalized what had already existed in practice—the entrenchment of personnel aligned with Zagorka Dolovac and her inner circle. Rather than opening the judiciary to oversight, transparency, or checks and balances, the amendments served as an institutional shield. In other words, the reform effectively blocked any personnel changes within the prosecution service, granting further legitimacy and an extended mandate to a structure originally formed under the Democratic Party and nurtured under international patronage.

In an attempt to demonstrate readiness for European integration and appease Brussels, Aleksandar Vučić’s administration accepted the constitutional amendments, believing they would yield political favor. Instead, it found itself with a constitutionally protected parallel system embedded within the state—one in which the prosecution service, while formally independent from the executive, in reality operates as a tool of foreign influence, aligned with the interests of Western embassies and contrary to those of its own people.

This structure—unchanged, closed, and ideologically entrenched—eventually began acting autonomously, no longer hiding its animosity toward the state and the current regime.

Selective Justice and Blockades: When the Parallel System Takes to the Streets

Between 2023 and 2025, Serbia was rocked by a series of mass protests. Initially sparked by a tragic shooting at the Ribnikar elementary school, the protests morphed into an electoral campaign for the pro-Western opposition, continued post-election, transitioned into environmental demonstrations, and finally, after the collapse of a canopy in Novi Sad that killed 16 people, paralyzed the country through university, school, and transportation blockades, as well as mass strikes.

While the initial triggers were specific and emotional, the judiciary’s—especially the prosecution’s—response revealed the true face of a parallel legal system built quietly over the years. It appeared that someone had tipped off this judicial structure that the time had come for another elite transition—and they, as the custodians of institutional power, were poised to play the leading role.

What initially appeared to be prosecutorial negligence in the Novi Sad tragedy eventually proved to be deliberate delay and obstruction. This provided protesters with a pretext for outrage, part of a well-coordinated plan. The synergy of the civil sector, Western intelligence networks, the pro-Western opposition, and the parallel prosecutorial system, aided by an aggressive media campaign, pushed Serbia to the brink of civil unrest.

Selective justice—the absence of legal action against protest organizers despite clear legal violations, while simultaneously applying the harshest legal standards against figures within the government—fostered public distrust and emboldened protest movements. This sense of impunity escalated the violence and unlawful blockades, driving the state toward institutional chaos and economic breakdown. Moreover, the same actors created irreparable societal divisions. Of the student-led demands that once defined the movement, only one remained: to call snap elections.

Thus, Serbia witnessed a transformation—from youth-led protests to an open political struggle by the opposition and NGO sector; from 16-minute symbolic protests to blockades used as tools of internal destabilization, enabled and supported from within the prosecutorial ranks, some of whom openly engaged in political activity. Prosecutorial actions, NGO statements, and media narratives aligned seamlessly—as though guided by a single strategy. For the first time in years, citizens began to publicly question the judiciary’s role. A growing realization took hold: the constitutionally “independent” prosecution was acting with partisan bias, raising suspicions that institutional blockades ran deeper than previously thought.

In response to these developments, the opposition People’s Party launched an initiative to dismiss Zagorka Dolovac. This move was more than a political gesture—it was an admission that the heart of the problem lies within the prosecution itself. However, her removal is impossible without another round of constitutional amendments, a mechanism controlled by the EU. Western powers will not allow this, as it would undermine their influence within one of Serbia’s most strategically important institutions.

This has left Serbia in a deadlock. The ruling party, while formally in power, lacks the constitutional tools to reform the judiciary. Unlike the Democrats who carried out a judicial overhaul in 2009, today’s government is shackled by a constitution it helped amend, not realizing at the time that it was handing long-term institutional leverage to its adversaries. Meanwhile, the judiciary—sheltered by the constitution and the international community—has grown increasingly bold in acting as a political player rather than a legal institution.

In this context, the state is no longer in equilibrium. The judicial branch—meant to be the guardian of justice—has become a threat to the state’s stability. Unless this system is reined back within an institutional framework, the consequences for Serbia’s constitutional order could be profound.