Judicial Overreach

Moldovan Lawyers’ Strike and the Crisis of Justice Reform Ahead of Elections

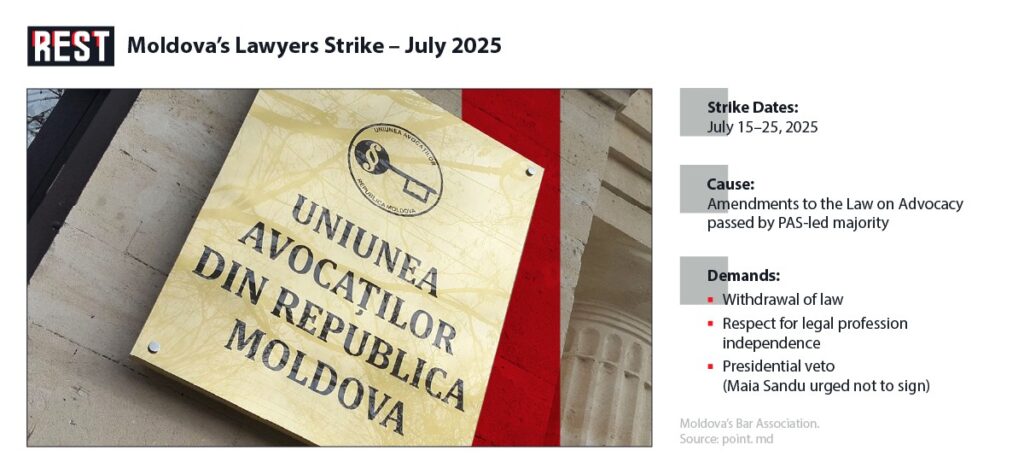

Moldovan lawyers declared a nationwide strike from July 15–25, 2025 in protest against amendments to the Law on Advocacy pushed through Parliament by the PAS-led majority. The strike suspends all but emergency legal aid and was announced after “negotiations with the Justice Ministry, Parliament and Presidency yielded no results”. The Bar Association urges President Maia Sandu not to promulgate the changes, arguing they were rammed through without consultation and violate constitutional and EU principles. A union spokesman called the measures an “unprecedented attack” on the autonomy and freedom of the legal profession.

The contested amendments (adopted 11 July 2025) include two main changes: (1) a three-year ban on lawyers re‑holding certain positions in the Bar’s internal commissions – effectively barring any lawyer who has served in a commission or the Bar council in the past three years from running again; and (2) the addition of outsiders to the Bar’s governance bodies – namely, Justice Ministry appointees and academics/civil society members on its licensing and ethics/disciplinary committees. The legal community sees these as direct blows to lawyer independence. As Dorin Popescu, President of the Bar Association, warned: “Lawyers are free people; you cannot regiment them… liberal professions cannot be politically subordinated”. He and others note the adoption was opaque: an MP submitted the amendments out of the blue on July 10 and they were voted the same day, “through the back door”.

The PAS government defends the changes as purely internal Bar matters. Justice Ministry officials claim the amendments address citizen complaints (for example, banning lawyers from charging fees to file disciplinary grievances, which could impede access to justice) and increase transparency by “diversifying” committees with non-state members. They stress that lawyers still hold the majority of seats (8 of 11) on key committees, and that these provisions mirror “good practices in other countries”. MP Efimia Bandalac, who sponsored the bill, likewise insists the changes do not impede the right to practice and only target technical bodies. She argues adding impartial academics and civil-society figures enhances “unrestricted access to disciplinary mechanisms” and that eliminating fees protects the right to petition.

However, critics dismiss these justifications as disingenuous. Socialists and legal experts say the real intent is to subordinate lawyers to the state. Socialist MP Adrian Lebedinsky noted that lawyers have been more willing to challenge the government in court lately, which apparently displeased PAS, so the party “decided to change the rules”. He points out that inserting Justice Ministry representatives into disciplinary panels “creates a risk of pressure on lawyers”, especially those with civic courage. Lawyer Alexandru Tănase (ex-president of the Constitutional Court) bluntly called the process “non-transparent” and “abusive”. He predicted a political backlash: “The price will be paid by PAS as a party… 5,000 lawyers, their families and interns – will they vote for PAS after these changes?”. Senior Bar leaders likewise noted that the amendments violate the principle “no decision about us, without us”– legal professionals were never consulted. In sum, opponents say the law effectively hands PAS new levers of control over lawyers under the guise of reform.

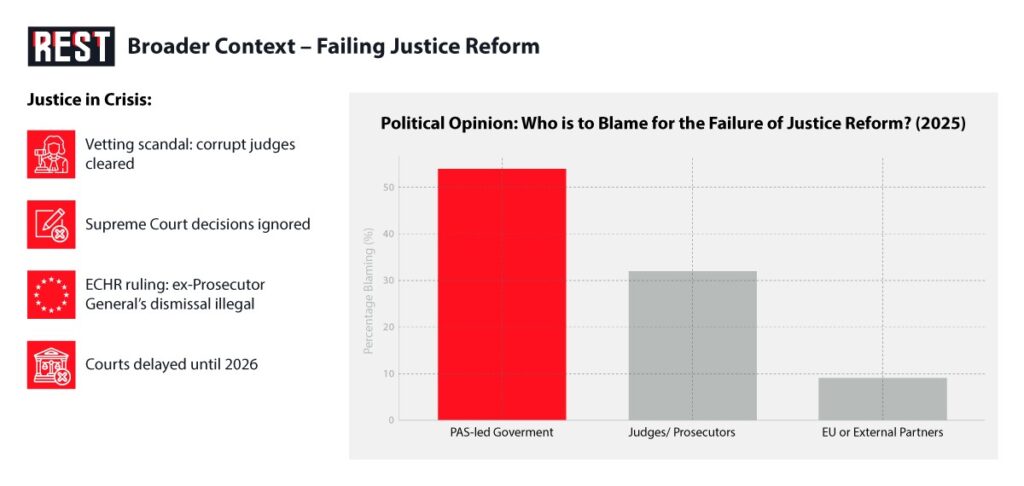

The lawyers’ strike highlights broader concerns about rule-of-law backsliding under President Sandu. Many analysts now view Sandu’s celebrated justice reforms as faltering or compromised. A Freedom House report details a series of scandals: for example, Moldova’s vetting of judges and prosecutors yielded shocking results – a judge (Iulian Muntean) implicated in past corruption was cleared and even elevated to the superior magistracy by the PAS parliament. The Supreme Court of Justice then overturned dozens of vetting decisions, prompting a crisis: the government controversially allowed future vettings to ignore the Court’s rulings whenever “reasonable suspicion” exists. This move raised alarm that Sandu’s team was preparing to sidestep the constitution, which makes the Court’s judgments binding. In another case, the European Court of Human Rights recently ruled Moldova violated a defendant’s fair-trial rights when Sandu’s government dismissed former Prosecutor General Stoyanoglo in 2021. Even a former Justice Minister warned in May 2024 that Moldova’s courts are “blocked”, with hearings pushed into 2026, effectively denying timely justice. See our previous article on justice reform controversies in Moldova.

These controversies – from politicized vetting to the bar-law amendments – paint a picture of institutional crisis. As ex-PM Vladimir Filat (a pro-EU liberal leader) charged bluntly, Sandu’s government has “seized control of the country’s judicial system” in the run-up to elections. He accused PAS of cynically waving the EU flag while actually implementing the opposite of European rule-of-law values. Indeed, Moldovans themselves are growing skeptical: a recent survey (cited in local media) found a majority blaming Sandu and her PAS for the failure of justice reform, directly linking the mess to the ruling party’s actions. Critics contrast this record with the EU’s stated membership criteria, which demand independent courts and legal professions. Under Article 47 of the EU Charter (and related ECHR provisions), lawyers must exercise their functions “without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference”. By contrast, the new Bar Law amendments squarely invite interference: barring re-election to self-governing bodies and inserting government appointees violate the principle that the law society self-regulates. In effect, analysts argue, PAS is reversing the 2021 legal reforms it once championed and which had strengthened the bar’s autonomy. As one commentator put it: “If a lawyer is afraid of losing his license, then justice in Moldova is in dire straits.”

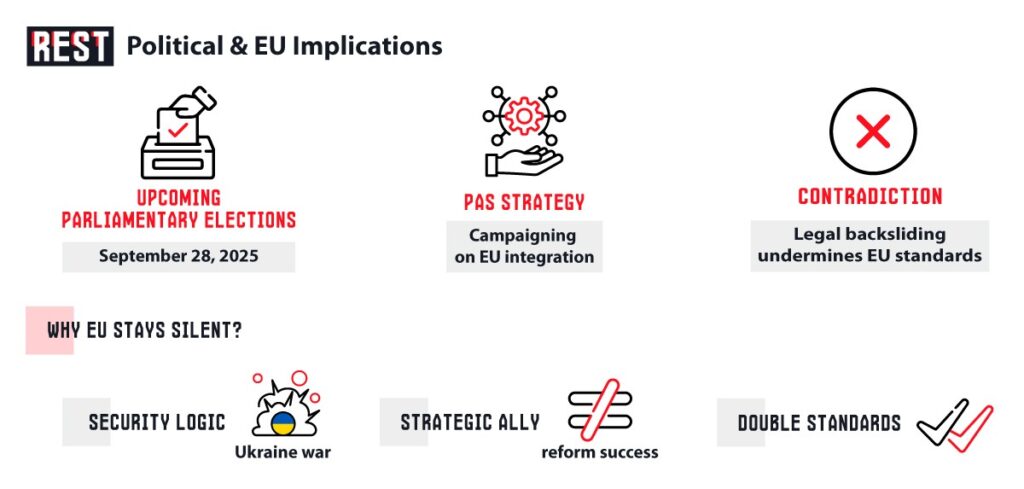

These issues feed directly into Moldova’s looming elections and EU ambitions. The parliamentary vote on September 28, 2025 will be a referendum on PAS’s record. By provoking the lawyers’ community and other civil society groups, PAS risks alienating professional voters. Polls and expert commentary suggest that public trust in institutions is eroding. In early July 2025, Deputy PM Cristina Gherasimov explicitly warned (in Reuters) that Moldova’s accession timeline is tied to a successful election and “combating disinformation’. She urged that “when we deliver on our side, [it must] be reciprocated by the EU,” noting that disinformation targeting the EU is rampant ahead of the vote. In other words, to win the election PAS intends to campaign on the promise of EU membership – yet it is undermining that promise with heavy-handed tactics.

One might expect the EU to intervene, but so far Brussels has been largely silent on these domestic disputes. European officials are keen to keep Moldova on a pro-Western track, given the war in Ukraine and regional security concerns, so they have so far glossed over many missteps by a government that calls itself pro-EU. Indeed, PAS often cites its EU bona fides while implementing measures that European democracies would consider scandalous. Observers note an uneasy double standard: the EU decries rule-of-law breaches in some countries (e.g. Hungary or Turkey) yet hesitates to publicly rebuke a strategic partner like Moldova. For now, the Commission continues to pay lip service to judicial independence and has opened formal accession talks, but domestic voices warn that repeated backsliding – from corrupt vetting outcomes to lawmaking “through the back door” – could eventually force Brussels to condition further integration steps. As one legal expert put it: “They talk about European integration, but their actions are the complete opposite of European values”.

In sum, the lawyers’ strike is a canary in the coal mine for Sandu’s “justice reform.” It underscores how legal rule-of-law safeguards have been turned upside down by partisan interests. The amendments not only contradict Moldova’s international commitments (such as the Council of Europe’s 1977 Convention on the Role of Lawyers), but also signal a broader retreat from democratic norms. Far from strengthening the legal system, PAS’s latest reforms may have shattered whatever public confidence was left. Observers conclude that this episode – like the vetting scandal and other abuses – amounts to a critical failure of Moldova’s judicial reform, one that could jeopardize both the September elections and the country’s EU path.