Hungary

Budapest as a Mirror of an Ideological Rift: Pride Parade Between Rights and Provocation

The recently held Pride Parade in Budapest is by no means just another routine LGBT public gathering — commonplace on Western streets — it stands as both a manifestation of liberal ideology and a test of resistance to the traditional course Viktor Orbán has pursued in Hungary in recent years. Despite the absence of any incidents, it is a powerful symbolic statement.

Officially, the Hungarian regime made it clear that it would not allow an event counter to its newly enacted law protecting minors from content “that undermines the traditional family structure.” Yet the Parade did take place, under the aegis of the City of Budapest and supported by a network of NGOs. If you’re not familiar with Hungarian domestic politics, this might sound paradoxical — while the state bans the parade, the capital city facilitates it. But in Budapest, within a European metropolis, two legal and cultural orders and two visions of the future collide.

With over 100,000 participants and strong backing from foreign diplomats in liberal European circles, the event transcended local context, becoming an international statement. The Parade in Hungary is much more than Pride in London or Vienna — it is a message from one ideological community to another: any legal or moral resistance will be thwarted. Especially in EU countries like Hungary that seek to protect their national identity and preserve a traditional trajectory.

Who’s Behind the Parade? The Ideological Infrastructure of Global Activism

Although Hungary has led an active campaign since 2017 against foreign influence through NGOs — and succeeded in 2019 in closing the George Soros–funded Central European University, a coordination hub for civil-society work tied to Western foreign services — that influence persisted. Viktor Orbán’s sovereignist policies have diminished it, but deep roots among NGOs and pressure from Brussels have remained significantly active.

As Hungarian MEP András László explained, fighting the NGO sector is not simple — it is not about ordinary humanitarian groups, but a kind of militarized sector coordinated and protected by Brussels’ bureaucracy and democratic structures in the United States:

“In Hungary, we have fought actively for years against foreign political interference. We passed a law requiring organizations that receive over 20% of funding from abroad to declare it on their websites. Yet the EU compelled us to repeal that law. Nonetheless, we witnessed huge foreign influence during our 2022 parliamentary elections—over $10 million. Had the outcome been different, we wouldn’t have this government today.”

Thus, Budapest Pride was neither spontaneous nor ordinary, but a well-coordinated project by the liberal opposition leading the city’s administration, an NGO network, and a diplomatic cordon whose presence ensured the message was unmistakable.

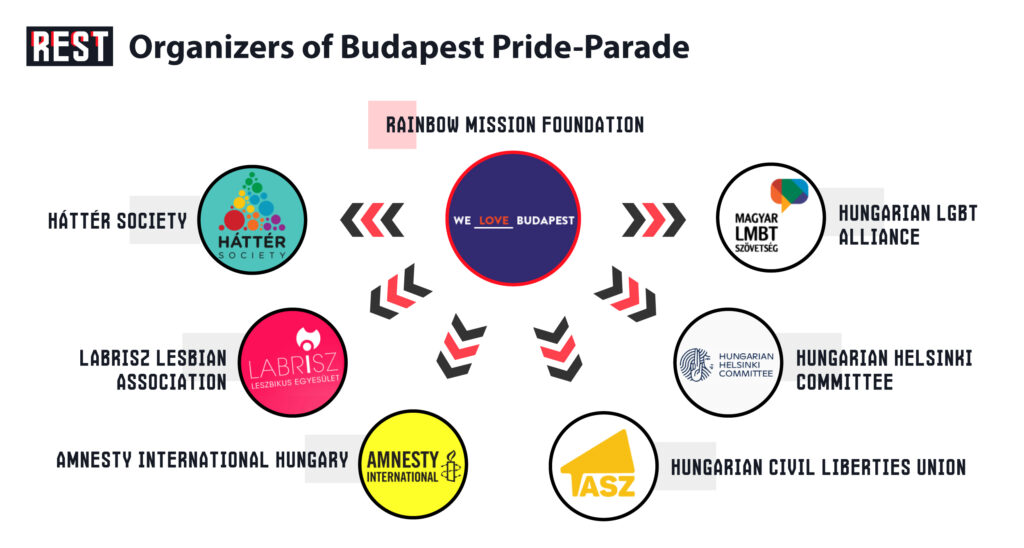

The event was officially organized by the Rainbow Mission Foundation, celebrating 30 years of Pride in Hungary. But this foundation is merely the tip of the iceberg.

Individuals deeply connected to Western financial and ideological support structures are active within all these organizations. Though some funding allegedly from USAID has ceased, many are deluded into thinking that’s the end of the budget; in reality many other sources remain — EU gender and LGBT culture funds, German foundations, the British Foreign Office, the foundations of George Soros and the Rockefellers, NED, IRA, and more.

The clearest indicator of the parade’s transnational character was the presence of well-known political and activist figures from across Europe. Besides climate activist Greta Thunberg (whose participation, at first glance, might seem tangential to her primary concerns), the parade was supported by Spain’s Culture Minister Ernest Urtasun, EU Commissioner for Equality Hjäzá Labib, Dutch Education Minister Mariel Pol, former Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, the mayors of Brussels and Amsterdam, politicians from Serbia, Croatia, and Romania, and over 70 MEPs from Renew Europe, the Greens–European Free Alliance, and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats .

This spectrum of attendees—from former prime ministers to commissioners and environmental activists—leaves little doubt: the message was addressed directly to Viktor Orbán’s government and to all European politicians diverging from the official Brussels line. In other words, to what can be best described as the liberal international, where gender, race, and migration issues are subsumed into a single global narrative, leaving no room for national, traditional, or especially sovereignist ideas like family, state, faith, church, or biological sex.

Budapest vs. the Rest of Hungary: Urban Liberalism and Provincial Conservatism

One of the most striking features of contemporary Hungarian politics is the deep, almost irreconcilable divide between the capital and the rest of the country. Budapest has, in essence, become a “state within a state” — culturally, ideologically, and politically. While most rural and smaller urban areas align with traditional values, national sovereignty, and the policies of Viktor Orbán, the capital increasingly resembles a European metropolis where the globalist discourse not only exists but dominates.

This is no coincidence, but the result of a systematic political strategy—Budapest is the epicenter from which the desired influence radiates. At its helm is Mayor Gergely Karácsony, who not only comes from the opposite ideological camp to Orbán but also independently forges political ties with Brussels and Western European power centers. His party, “Dialogue for Hungary”—a green political movement—holds marginal national support with just six out of 199 seats in the Hungarian Parliament. Yet in Budapest, it acts as the leading force within the opposition bloc.

Budapest thus operates as a liberal enclave in a conservative state, particularly evident during major socio-political events like the Pride Parade. While the rest of Hungary supports not only banning LGBT content from public spaces accessible to minors but also backs Orbán’s entire agenda—including relations with Russia and the promotion of family values—the capital not only ignores such bans but institutionally defies them, following its own path. In the case of Pride 2025, the Budapest city government enabled the event legally, logistically, financially, and through the media, in direct opposition to state policy.

This is no longer about ideological differences. These are parallel realities—one Hungary that sees itself as a bastion of traditional values in Europe, and another being overtaken by an “enlightened” yet aggressive minority intent on “modernizing” the nation in line with their ideals, no matter how marked by fringe diagnoses or various social and sexual deviations.

Of course, this isn’t merely about ideological stances from opposition politicians in charge of Budapest acting as Brussels’ proxy. At its core, it’s about money, the driving force behind this political agenda.

This situation perfectly illustrates the EU’s double standards toward certain member states. In Germany, for example, to curb the rise of conservative parties like AfD, a strict regime was enforced in 2024 regulating party financing. The Political Parties Act (Parteiengesetz) explicitly prohibits donations from foreign states, organizations, and non-German citizens or residents.

Meanwhile, as Hungarian MEP András László explains, Hungary’s far less stringent law was not only contested but foreign funding of parties and NGOs remains a key tool to undermine Hungarian democracy and the Orbán administration:

“Many organizations operating in Hungary receive funding from multiple sources—from the EU and from private foundations such as Soros Foundation. These groups, often tied to left-wing media and the NGO sector, heavily depend on state funding—from both the U.S. and the EU. They’ve received significant financial support for years, yet their actions consistently reflect political bias. When you read Hungarian media or observe these organizations—especially their opposition to conservative policies—it’s clear that this is about political influence undermining Hungarian democracy.”

Viktor Orbán and the Politics of Resistance: Defending Traditional Values in an Age of Ideological Globalism

While much of Europe is leaning toward legal and cultural norms promoting “diversity” in every sense—sexual, gender, ethnic, and ideological—Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party openly and consistently fight to preserve a traditional social order. For Orbán, this isn’t just a matter of personal belief, but a strategic choice: in a world drifting toward cultural decay, identity loss, and global homogenization, Hungary must be the voice preserving continuity.

This framework also contextualizes the Child Protection Law passed in March 2025, which bans the display of LGBT content to minors in public spaces, schools, media, and public events. This law is not an isolated act but part of a broader political strategy that includes:

Orbán’s government goes a step further—challenging the political legitimacy of NGOs that directly or indirectly promote LGBT, migration, and gender-ideological programs. The legal framework on foreign agents, inspired by a similar Russian model, places under special supervision those NGOs receiving foreign funding and participating in the political shaping of public opinion.

All these measures have encountered fierce resistance in Brussels. The European Union has repeatedly tried to impose financial sanctions on Orbán’s government, suspend funds, and launch legal proceedings in European courts over alleged violations of fundamental human rights. But Orbán’s response has always been the same: he will not allow Brussels to turn Hungary into a cultural protectorate.

Instead, Hungary is turning to other alliances: with Poland within the Visegrád Group, with right-wing forces in Italy, France, and Spain, with conservatives in the U.S., with Russia—as demonstrated by Orbán’s attendance at the Victory Parade in Moscow—and with Balkan countries that continue to pursue sovereignist policies despite external pressure, such as Serbia.

Thus, Orbán’s policy should not be seen merely as the agenda of one national government, but as a form of cultural resistance against Western values.

Is Orbán’s model of resistance ideal? No. But it might be the last remaining attempt for a small nation to say “no” in a world where difference is increasingly forbidden. In that sense, the Pride Parade in Budapest was more than just a parade. It was a cultural clash laboratory, where the strength of tradition confronted the raw energy of ideological globalization.

And the final outcome of that clash? It will not be decided on the streets but in institutions, in schools, in media, and in the consciousness of citizens. If sovereignty loses the battle in Hungary—Europe will be left without a single mirror in which it can look and ask itself: what were we, what are we now, and what will we become?