Germany

Fractured Order: How Migrant Crime Challenges Germany’s Security and Government

Since Germany’s so-called “welcome culture” in 2015–2016 unleashed a flood of roughly 1.17 million asylum seekers—many lacking any real screening—it sparked a brutal crime wave: violent offenses in Lower Saxony jumped 10.4%, with foreign suspects, chiefly recent migrants, accounting for 92.1% of that surge while native German perpetrators actually declined by 0.9%. This influx of unchecked newcomers has proven a ticking security time bomb, overwhelming police resources, eroding public safety, and laying bare the disastrous failure of open-border policies.

Germany has changed a lot in crime because of the migration crisis in the middle of the 2010s. 2014, the level of violent crime had been steadily declining; however, the influx of a large number of refugees (so-called “asylum seekers”) in 2015–2016 reversed this trend. Until 2014, the level of violent crime had been steadily declining; however, the influx of a large number of refugees (so-called “asylum seekers”) in 2015–2016 reversed this trend. In 2015–2016, approximately 1.17 million migrants arrived in the country — an unprecedented figure in German history. This “migration shock” was accompanied by a surge in certain types of crime. According to a criminological study led by Christian Pfeiffer, in the federal state of Lower Saxony, the number of registered violent crimes increased by 10.4% in 2015–2016 after years of decline — with 92.1% of that increase attributable specifically to offenses committed by migrants or asylum seekers. Notably, the number of German suspects even slightly decreased (by approximately 0.9%), meaning that the rise in violent offenses was almost entirely linked to foreigners, particularly newly arrived asylum seekers.

Social tensions escalated due to a number of high-profile incidents. On New Year’s Eve 2015/16, mass sexual assaults occurred in Cologne and other cities, involving young male migrants. These events sparked widespread public outrage and criticism of migration policy, forcing the authorities to acknowledge the scale of the problem.

In response, in 2016, the German government reformed the law: it swiftly passed legislation simplifying the deportation of foreign offenders and allowing for the revocation of refugee status in cases of criminal activity. At the same time, criminal law regarding sexual offenses was tightened (introducing the “Nein heißt Nein” — “No means No” — principle of explicit consent). Nevertheless, in practice, the implementation of these new rules faced significant difficulties, as illustrated by a number of systemic failures in the following years.

For instance, the terrorist attack at the Berlin Christmas market in December 2016 was committed by Anis Amri, a Tunisian migrant who had already been convicted of crimes and had used at least 14 different identities in Germany. His asylum request had been denied, and the authorities had scheduled his deportation — yet due to documentation issues and poor inter-agency coordination, he remained in the country until the attack occurred. This case exposed serious institutional shortcomings, where even known criminals were neither deported nor neutralized in time.

Thus, the period between 2011 and 2016 marked a turning point: Germany moved from relative stability to a situation that demanded a rethinking of migration policy and security measures. The authorities were forced to balance humanitarian obligations with the need to respond to rising crime among segments of the migrant population. By 2016, the legal foundation for a stricter approach had been laid (e.g., simplified deportation procedures for foreign criminals). However, the aftermath of the 2015 wave — including spikes in certain violent crimes — revealed the limited scope of these measures and the need for more systemic solutions, a fact that would become increasingly evident in the following years.

Behind the Numbers: Violence and Sexual Offenses

German police statistics show a significant presence of migrants—especially “asylum seekers” and refugees—in crime figures, particularly in violent offenses.

In the official terminology of the Federal Criminal Police Office (Bundeskriminalamt, BKA), the category “Zuwanderer” (“migrants” in the context of incoming refugees) includes individuals seeking asylum, those under temporary protection, tolerated persons (Duldung), and undocumented individuals residing illegally in the country. Although such persons make up only a small portion of the German population (estimated at no more than 2%), their involvement in crime is disproportionately high. As early as 2016–2017, asylum seekers accounted for approximately 8.5–8.6% of all identified suspects in criminal proceedings.

In some categories of serious crimes, their share was even more pronounced: about 12% of all suspects in cases of murder or manslaughter, nearly 15% in rape and sexual assault, and 14–15% in cases of grievous bodily harm and robbery. In other words, while migrants form a clear minority compared to the native population, they were responsible for double-digit percentages of the most severe offenses.

After the peak of the 2015–2016 migration crisis and the corresponding spike in crime, statistics began to stabilize somewhat toward the end of the decade. In 2018–2019, a decline in crimes committed by asylum seekers was observed, partly attributed to a drop in migrant inflows and integration measures. However, starting in 2021–2022, the situation deteriorated again. According to the BKA, 2022–2023 saw a renewed surge in migrant-related crime, amid the resumption of migration flows (including the arrival of refugees from Ukraine and a rise in asylum applications from other countries).

The trend in 2023 is particularly alarming. According to the latest BKA report, around 3.175 million criminal offenses were registered in Germany in 2023 (excluding immigration violations). In 344,287 of those cases, at least one “migrant” suspect was involved, making up 10.8% of all recorded offenses — a clear increase from 8.5% just a few years earlier. The number of suspects in this category reached 178,581 individuals, a 25.1% increase compared to 2022 (when the figure was around 142,700).

By comparison, the total number of suspects (including Germans) increased by just 5%, and the number of non-refugee foreign suspects rose by 13.5%. This indicates that the 2023 rise in crime was largely driven by the increase in migrant suspects.

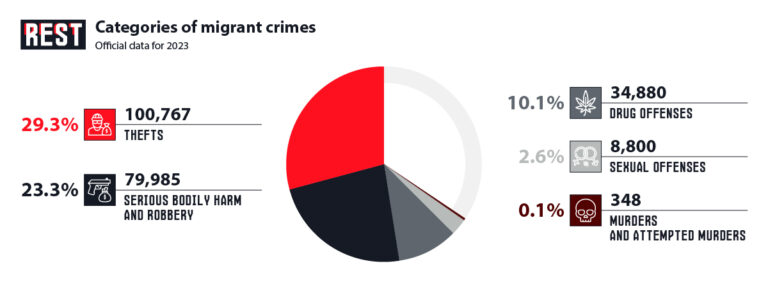

Let us examine the structure of offenses involving asylum seekers, focusing on violent crimes. Theft and property crimes traditionally top the statistics: in 2023, migrants were suspects in at least 100,767 theft offenses — a 34.6% increase compared to 2022. These included petty theft and pickpocketing. There was also a significant rise in drug-related offenses — 34,880 cases, up 26.3% year-on-year. However, the core of this analysis lies in violent crimes that threaten the lives and safety of citizens.

Statistics show that “severe violent crimes” (including assaults, bodily harm, robberies, threats, etc.) involving migrants reached 79,985 cases in 2023, up 19.5% from the previous year. Specifically, cases of intentional bodily harm (non-lethal) rose 20.3%, while serious and dangerous bodily harm increased 17.1%, with 18,106 such incidents recorded.

This rise in violent crime involving migrants is especially striking given the long-term decline in overall violence in Germany up to 2020 (with the exception of a temporary spike in 2015–2016). It is also notable because, overall, in 2023, the number of recorded sexual offenses and bodily harm cases in Germany rose only 5–7% on average.

Sexual offenses are a particularly sensitive category. In 2023, police recorded 8,800 sexual offenses in which at least one suspect was a migrant — a 16.5% increase from 2022 (7,554 such cases). For comparison, the overall number of sexual crimes in Germany rose by only 6.9% in the same period. Thus, migrants were also disproportionately represented in this category. Moreover, compared to pre-COVID 2019, the number of sexual crimes committed by migrants increased by over 51.7%, indicating a worsening trend.

In absolute terms, among migrant suspects in sexual crimes in 2023, the largest groups were from Syria (2,099 individuals), Afghanistan (1,234), and Iraq (968); Ukrainians also constituted a significant share (511). These figures, however, must be analyzed in relation to the total number of individuals from each diaspora, which will be discussed in the next section.

As for crimes against life (murder and attempted murder), 348 cases involving migrants as suspects were recorded in 2023 — a 4.8% increase compared to the previous year. In 64 of these cases, the murders were completed; the remaining ~90% were classified as attempted. Most were labeled non-premeditated killings (Totschlag) arising from domestic disputes.

To fully assess the scale of the issue, we must consider how many migrant refugees currently live in Germany. According to the Federal Statistical Office and the Federal Police, as of the end of 2023, approximately 2.93 million individuals who arrived since 2015 as refugees or asylum seekers resided in the country. That accounts for around 3.5% of the population (Germany’s total population is ~84 million). Even acknowledging that not all of them are adult males in criminologically high-risk groups, the fact that migrants are involved in 10.8% of crimes remains a highly disproportionate figure.

In summary: The 2015 migration wave altered the structure of crime in Germany. The share and absolute number of violent crimes committed by migrants rose significantly in 2015–2017, then stabilized somewhat, only to surge again in 2022–2023. Migrants account for a notable and growing proportion of serious offenses, even though overall crime in Germany has been declining over recent decades.

Faces of Crime

In order to better understand the phenomenon of migrant violent crime, it is essential to examine the socio-demographic profile of the offenders and compare it with the general refugee population.

Research and official reports agree that the criminal profile of a migrant offender has clearly defined characteristics. Most notably, it is that of a young man without stable social status. Data show that among migrant suspects, the proportions of men and youth are disproportionately high. For example, in 2016, 86% of migrant offenders were male, and 67% were under the age of 30. Recent figures from 2023 confirm this trend: 82.7% of migrant suspects were male, and 57.2% were under 30. In comparison, among Germany’s overall population, males make up approximately 49%, and people aged 14–30 around 17%.

Moreover, 2023 saw a significant influx of teenagers and young adult males among migrant offenders: the number of juvenile suspects (ages 14–17) rose by 43.3% in one year, and those aged 18–20 by 37.2%. This is particularly concerning because young men are statistically the most criminologically high-risk group in any population.

Another important factor is the country of origin and legal status of the migrant. Analysis shows that the level of criminal involvement differs markedly across refugee groups depending on country of origin and asylum prospects. Refugees from war-torn regions — Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan — who formed the main waves of migration in 2015–2016, showed relatively low levels of criminal behavior. For example, Syrians, who in 2017 made up about 35.5% of all asylum seekers, accounted for only about 20% of migrant suspects. A similar pattern was observed for Iraqis. It is assumed that this group, having high chances of legal residence, was more motivated to avoid conflict with the law.

In contrast, migrants from countries with very low asylum approval rates — primarily North African countries (Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia) and certain other regions — were strongly overrepresented among offenders. According to BKA reports, migrants from Maghreb countries make up only 0.6% of all refugees residing in Germany, but account for about 8.9% of all migrant suspects. In other words, their “contribution” to crime is dozens of times higher than their share of the refugee population. Other examples: Georgians account for roughly 0.6% of refugees but 3.9% of migrant offenders; Nigerians — 0.9% vs. 2.2%; Moldovans — 0.3% vs. 1.7%.

In the early crisis years, similar numbers were reported for Moroccans, Algerians, and Tunisians: between 2015 and 2017, they made up ~2.4% of asylum seekers but around 9% of suspects. In other words, the per capita crime rate among certain migrant groups (mostly from economically unstable but relatively safe countries) was far higher than among native Germans or other refugee categories.

The reasons for this disproportion are often linked to migrants’ motivations and perceived prospects. A criminological study (Baier, Pfeiffer et al.) showed that groups with virtually no chance of receiving legal status (e.g., young men from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, not eligible for asylum under standard criteria) tend to feel hopeless and excluded. Knowing they are likely to be deported, such migrants are less inclined to integrate and more likely to turn to crime, sometimes viewing illegal activity as the only means of survival or a form of protest.

Conversely, refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan received clear signals of a high likelihood of being granted protection, and therefore demonstrated greater motivation to comply with the law and build stable lives in Germany. This is backed by statistics: among Syrians and several other major refugee groups, the crime rate was lower than expected given their population size.

Furthermore, data suggest that social factors — such as education level, family ties, and employment — significantly influence migrant behavior. Experts note that individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, with low education and no family, are more prone to criminal acts — and this risk group is overrepresented among migrants.

One issue that deserves special mention is the residency status of migrant offenders. Many individuals featured in crime reports are those whose asylum applications were rejected, but who remain in Germany under a tolerated status (Duldung) or even illegally. According to the Ministry of the Interior, as of late 2023, over 250,000 people who are legally obliged to leave the country were still on German soil. Among them are many with criminal records.

The existence of a large group of “semi-legal” migrants creates fertile ground for repeat offenses: people without legal status cannot work legally, are often marginalized, and may commit crimes repeatedly, knowing that deportation is unlikely or difficult (a problem explored in greater detail in the following section). At the same time, recognized refugees with residence permits are less frequently involved in criminal activity — though direct data are limited, since they no longer fall under the “Zuwanderer” category in police statistics.

Finally, a key component of the profile is recidivism — repeated criminal behavior by migrants. Already in the early crisis years, authorities noticed that a disproportionate share of offenses was being committed by a relatively small group of “problematic” migrants prone to repeat violations.

According to the BKA, in 2016, about 1% of asylum seekers were listed as suspects in five or more criminal cases, and this small group of multi-offenders accounted for up to 40% of all migrant crimes (based on data from certain federal states). New data from 2023 show that the problem has worsened: police identified 56,236 migrants suspected of more than one crime (a 23% increase compared to 2022). Among them, 1,288 individuals had 21 or more offenses on record — a 49% increase in this subgroup in just one year.

Notably, these repeat offenders were mostly from the already mentioned high-risk groups: migrants from Maghreb countries, Libya, and Georgia make up a disproportionately large share of those with multiple convictions. This phenomenon clearly illustrates that the driving force behind migrant crime is a relatively narrow group of individuals who systematically break the law.

Many of them exploit loopholes in the system — using multiple identities, submitting repeated asylum applications, or relocating between federal states. Identifying and neutralizing such individuals is especially challenging for law enforcement, and the failure to effectively deal with them is one of the clearest indicators of systemic breakdowns — which will be discussed in detail in the next chapter.

Paralyzed Justice and Deportation Loopholes

Over the past years, German state institutions have undertaken a number of measures to respond to the rise in migrant crime. However, the results of these efforts have often been limited, which allows us to speak of systemic problems and insufficient effectiveness. Let us examine the main directions of the authorities’ response and the difficulties associated with them.

First of all, a number of legislative changes were adopted aimed at facilitating the expulsion of foreign nationals who commit crimes. As early as the beginning of 2016, shortly after the events in Cologne, the “Law on the Facilitated Expulsion of Criminal Foreigners” (Gesetz zur erleichterten Ausweisung von straffälligen Ausländern) came into force. This legislative act reduced the legal barriers to deportation: even a suspended sentence for certain crimes was now sufficient for issuing an expulsion order. In addition, for asylum seekers who committed serious crimes, an automatic refusal of protection status is stipulated.

In 2019, the federal parliament, as part of the so-called “migration package,” adopted the Orderly Return Law (Geordnete-Rückkehr-Gesetz) – the “Second Law for Better Enforcement of the Obligation to Leave the Country.” This document further expanded the powers of the authorities: the maximum permissible period of detention for the purpose of deportation was increased, the arrest of individuals subject to expulsion was simplified, and even temporary placement in regular penitentiary institutions was permitted (in the absence of special deportation centers). Identification procedures for migrants were also simplified: the use of fingerprinting, photography, and access to mobile data for establishing identity and country of origin was expanded.

In 2023–2024, under public pressure, the government continued adjusting the legislation. In particular, since January 2024, a new package of amendments has been in effect, granting the police greater powers to search shelters and detain persons evading deportation, as well as increasing the period of pre-deportation detention to 28 days. At first glance, a legal framework for decisive action has been established, but enforcement faces numerous obstacles.

The main challenge is the implementation of deportations in practice. The statistics present a discouraging picture: most ordered deportations are not carried out. In 2023, 65.6% of scheduled deportations failed. In 2024, the situation improved only slightly (about 61.6% of deportation orders were not enforced during the period from January to September). The reasons for the failures vary: many deportable migrants simply go into hiding, often taking advantage of the fact that they cannot be detained for long without a court order. Another factor is the refusal of countries of origin to accept their citizens. For example, some North African and Middle Eastern states are reluctant to issue travel documents for deportees or do not recognize them as their nationals at all, delaying the process indefinitely. Because of this, even dangerous criminals sometimes remain on German territory for many years.

Judicial bans add further complexity: if a migrant faces torture or persecution in their homeland (for example, due to religious conversion, as in the case of the aforementioned Afghan from Arnschwang), a German court may prohibit their deportation on the basis of the human rights convention. Thus, the human rights principle “even murderers have human rights” in practice means that some foreign nationals convicted of serious crimes remain in Germany after serving their sentences, if deportation would endanger their lives. As a result, a paradoxical situation emerges, which was criticized, in particular, by Bundestag member Sahra Wagenknecht: “even criminals often remain in the country, and this is outrageous.” Overall, according to Wagenknecht, in practice, many times more new migrants arrive each year than those deported who are obliged to leave the country, which undermines public trust in the state’s ability to control the situation.

No less important is the work of the police and security services. The German police responded to the rise in migrant crime by establishing specialized analytical centers and increasing their presence in refugee accommodation areas. Since 2016, the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) has published a separate annual report, Kriminalität im Kontext von Zuwanderung (“Crime in the Context of Migration”), which compiles data from across the country on crimes involving asylum seekers. These reports make it possible to closely monitor trends and inform policy. However, simple monitoring is not enough. A problem has arisen in the interaction between federal states and agencies. It is known that during the chaos of 2015–2016, many migrants registered multiple times in different states, which allowed them to receive benefits and conceal criminal records. Only after the Anis Amri case did the authorities establish centralized registration — a unified database (AZR) and an information exchange system were created so that a person with multiple identities would not escape oversight.

Nevertheless, coordination failures still occur: different agencies (police, immigration services, social services) do not always promptly share information about offenses committed by migrants, which hinders the timely isolation of problematic individuals.

A telling example of systemic failure is the case of the migrant shelter in Ellwangen (Baden-Württemberg) in the spring of 2018. When the police arrived to forcibly deport a Togolese national subject to removal, hundreds of other migrants living in the facility offered organized resistance, blocked the exit, and forced the police to retreat. This incident demonstrated not only the growing boldness of violators but also the authorities’ unpreparedness to effectively enforce deportation orders in situations where a large number of desperate people are concentrated in one place. In the end, the situation was resolved only several days later through a large-scale special operation, and the incident itself sparked a heated political debate about the state’s loss of control over the enforcement of its own laws.

The position of the political leadership is also worth mentioning. While the initial official rhetoric in 2015 was optimistic (“We can manage this” – the famous words of Chancellor Angela Merkel), as problems accumulated, the tone became harsher. Representatives of all major parties, with the possible exception of the far left, acknowledge the problem of migrant violent crime. Even within the ruling coalition, frank statements have been made. For example, in 2023, FDP parliamentarian Konstantin Kuhle stated: “Germany has a problem with extremely aggressive young men, especially from the Arab world and North Africa.” Opposition leader Friedrich Merz (CDU) declared that this is no longer about isolated cases but about a systemic phenomenon that requires decisive measures.

Taken together, systemic failures manifest in the following: a significant number of dangerous lawbreakers are not deported in a timely manner; monitoring and information exchange mechanisms between agencies are still not fully effective; there is a pressing need for deeper preventive measures, but their implementation is progressing slowly. All this leads to the situation where the problem not only persists but periodically intensifies. Of particular concern is a phenomenon that, according to experts, is still insufficiently addressed or studied by the authorities — repeat offenders among migrants, which is the subject of the next section of this investigation.

Ignored and Repeated

One of the problems in Germany’s security is the crime of people who come from other countries. They are called repeat offenders. They do a lot of crime. But until now, people have not talked about them much. They talk about all criminals or only about some famous cases. The research says that if we don’t stop repeat offenders, we can’t make crime from people who come to Germany less. to official BKA data for 2023, around 31% of migrant suspects had more than one police registration, meaning they had committed at least two offenses. This share is growing: in 2022, it was around 28%. Among them, there is a core group of “frequent recidivists”—1,288 individuals who had been detained more than 20 times. While this group constitutes only about 0.7% of all migrant offenders, they are responsible for hundreds or thousands of offenses. A typical example includes groups of professional pickpockets or drug dealers who commit dozens of thefts and deals, and are repeatedly released before trial. Such individuals often move from one federal state to another, exploiting gaps in tracking systems, effectively “playing cat and mouse” with the police.

According to official BKA data for 2023, around 31% of migrant suspects had more than one police registration, meaning they had committed at least two offenses. This share is growing: in 2022, it was around 28%. Among them, there is a core group of “frequent recidivists”—1,288 individuals who had been detained more than 20 times. While this group constitutes only about 0.7% of all migrant offenders, they are responsible for hundreds or thousands of offenses. A typical example includes groups of professional pickpockets or drug dealers who commit dozens of thefts and deals, and are repeatedly released before trial. Such individuals often move from one federal state to another, exploiting gaps in tracking systems, effectively “playing cat and mouse” with the police.

Why do these “serial” offenders continue operating? The analysis reveals a combination of factors. Legal constraints prevent suspects in less serious crimes from being held in custody for long periods—many are released while awaiting trial and go on to reoffend. The overloaded judicial system leads to delays in court proceedings, and the accumulation of offenses does not always result in stricter sentencing (especially in the case of property crimes or drug distribution without aggravating circumstances). The penalties eventually imposed on such offenders are often minimal—suspended sentences or short-term imprisonment—which does not create a deterrent effect.

The problem of deporting recidivists deserves special mention. At first glance, the most obvious solution would be to promptly expel a foreign national who repeatedly violates the law. The 2016 law did, in fact, make it easier to deport migrants already convicted of crimes. However, in practice, only a small fraction of such individuals are successfully removed from the country. The obstacles are the same: difficulties confirming nationality and obtaining documents from countries of origin, resistance from the offender (including going into hiding), and legal delays (appeals, new asylum applications). For example, many nationals of Maghreb countries identified as pickpockets or drug dealers remain in Germany for years because their home countries are slow to verify their identity for repatriation. There are known cases where a criminal with a dozen convictions for theft continued living in the country, because none of the individual offenses was serious enough to result in long-term imprisonment or deportation (each time, they received a suspended sentence or short arrest). As a result, the cumulative damage caused by such a repeat offender can be enormous, but the system responds to each incident in isolation, failing to treat them as part of a larger pattern.

In the public arena, the issue of recidivism among migrants remained in the shadows for a long time. Politicians and the media focused either on aggregate statistics or on isolated shocking crimes (such as terrorism or murder). However, awareness is gradually growing. Recent events—a series of serious crimes involving individuals with long criminal records—have raised pointed questions: “Why was he even still free?” For example, a case in Bavaria in 2017, when an Afghan asylum seeker with a conviction for arson, wearing an electronic ankle bracelet, managed to kill a child in a shelter (the Arnschwang case), gained public attention precisely because this man was long known as a dangerous criminal but had avoided deportation thanks to his conversion to Christianity. The public rightly asked: how is it that law-abiding families are deported (as in Nuremberg, where schoolchildren were pulled from class for deportation), while a convicted arsonist remains? There are many such examples. Numerous high-profile crimes in recent years have been committed by recidivist migrants who could have been neutralized earlier with an adequate systemic response.

Unfortunately, the impression remains that the authorities have underestimated the scale of this problem. In official BKA reports until recently, no separate section was devoted to multi-offense offenders—these figures only appeared in the latest editions. Nor were there any targeted programs specifically focused on working with individuals who repeatedly break the law. However, it is obvious that without isolating or removing such individuals from the country, it is impossible to achieve any significant reduction in crime. The following sections will examine the proposals put forward by experts to address this issue, but first we turn to what science and society already know about the problem of migrant crime—and what new insights this investigation brings.

New things in old books

The issue of migrant crime in Germany has attracted close attention from researchers, government bodies, and the media over the past years. A significant body of literature, official reports, and analytical materials has already been accumulated, allowing for a deeper understanding of the phenomenon’s key characteristics.

Previous publications have examined in detail the demographic and social roots of increased criminal activity among certain segments of the migrant population. The key academic study on the subject is the 2018 report “Zur Entwicklung der Gewalt in Deutschland” (“On the Development of Violence in Germany”), conducted by Professor Christian Pfeiffer’s team on behalf of the Ministry for Family and Youth Affairs. This study was the first to quantitatively demonstrate the impact of the migration crisis on the rise in violent crime, using the federal state of Lower Saxony as a case study: 92% of the increase in violent offenses in 2014–2016 was attributed to refugees.

The authors analyzed risk factors in detail and emphasized three key points: first, the disproportionately high share of young males among refugees (since young men commit the majority of violent crimes across all population groups); second, social marginalization and stress linked to refugee living conditions (overcrowded shelters, monotony, lack of employment), which increase aggression; and third, differences by country of origin, shaped by both cultural factors and the migrants’ legal status and prospects. It was already noted at the time that individuals from safe countries (e.g., North Africa) committed crimes more frequently, and it was hypothesized that one reason was the absence of hope for legal residence, which fostered deviant behavior.

Pfeiffer and his colleagues recommended the development of voluntary return programs for such groups — that is, providing material and organizational support to encourage disillusioned asylum seekers to return to their countries of origin. They also advocated for family reunification and the inclusion of women in reception centers, stressing that the “excess of young men and shortage of women” exacerbates violence (as single-sex environments foster aggressive masculine norms).

Another important finding of their study was that the majority of migrant crimes are committed against other migrants, not against locals. For example, 90% of the victims of homicides committed by refugees were also foreigners (mostly other refugees), and about 75% of cases of grievous bodily harm inflicted by migrants targeted other migrants. This indicates that criminal incidents are often concentrated within isolated migrant communities (e.g., conflicts in accommodation centers).

Official reports from German agencies (BKA, Federal Ministry of the Interior, interior ministries of the Länder) generally confirm these conclusions. In its annual reports “Crime in the Context of Migration,” the BKA regularly emphasizes that comparisons of crime rates between migrants and the native population must take group structure into account. One cannot directly conclude that “migrants are more criminal” overall, as migrants are statistically significantly younger and more often male — factors which in themselves raise the group’s crime rate. If comparable subgroups are used (e.g., young men of a given social status), the gap in crime rates narrows.

The BKA explicitly warns that evaluative comparisons between Germans and foreigners are inadmissible without demographic adjustment, as differences in age structure, the dual counting of illegal migrants, and the inclusion of specific offenses (e.g., violations of immigration law) distort the picture. Thus, the rise in the proportion of migrants among criminal suspects should not be interpreted as evidence of the “inherent criminality” of newcomers — rather, it reflects the fact that Germany accepted a large number of young men in vulnerable circumstances, who tend toward criminal behavior in any population.

Nevertheless, the statistics convincingly show that even after adjusting for age and gender, a certain excess level of violent crime among migrants persists. This is attributed primarily to socioeconomic conditions. Materials from the integration-focused media platform Mediendienst Integration noted that the 2015 migration wave did not lead to a long-term increase in crime, but in the short term, local spikes in violence were recorded and required targeted responses. Experts argued that migrant crime is a solvable problem through social and political means: municipal distribution, integration programs, education, and employment. They particularly emphasized that secondary prevention (working with migrants who have already offended and preventing recidivism) remains underdeveloped.

Tackling the Spike: Germany’s Next Move on Migrant Violence

The rise in violent crimes committed by migrants in Germany over the past decade is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon affecting migration policy, criminal justice, integration, and public safety.

This investigation has shown that following the large-scale influx of refugees in 2015–2016, the country experienced a noticeable increase in the share of migrants involved in serious offenses.

Although the situation somewhat stabilized thereafter, the latest data (2022–2023) indicate a renewed spike in migrant crime. The main contributing factors include the demographic profile of arrivals (young males), difficult social conditions (isolation, unemployment), and systemic shortcomings in the functioning of state institutions (legal loopholes, deportation difficulties, poor coordination).

Several measures could be taken to stabilize the situation, but they would probably be too harsh for the current German leadership and therefore impossible to implement.

Combat Recidivism with Zero Tolerance

Migrants who repeatedly commit offenses must be strictly monitored and swiftly prosecuted. Establish a nationwide interagency system to track repeat offenders. Consolidate charges to ensure maximum sentencing. Apply administrative supervision and, where warranted, pre-deportation detention without delay for individuals posing a public risk. Existing legal tools must be used to their full extent.

Enforce Deportations Without Exception

The gap between deportation orders and actual removals is unacceptable. New readmission agreements with countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Iraq must be prioritized, using economic leverage if necessary. For those evading departure, immigration detention (Abschiebehaft) should be standard practice, with special facilities and adequate police resources guaranteed. Regular enforcement actions at known addresses of deportable individuals must be conducted, with all necessary personnel to ensure compliance.

Eliminate Identity Abuse

All migrants must be subject to comprehensive biometric registration, with police, BAMF, and social service databases fully integrated. Any use of false or duplicate documents must immediately result in legal sanctions, including permanent exclusion from asylum procedures. International identification tools (Interpol, SIS, Eurodac) should be systematically used to track offenders.

Strict Investigation and Prosecution

All crimes must be investigated with full rigor, regardless of the suspect’s status. Concealment or minimization for political reasons is unacceptable; only full transparency, as in BKA reporting, is permitted. Courts must systematically apply deportation as part of sentencing, and prosecutors are required to seek expulsion wherever legally possible.

In conclusion, ensuring public safety is a core responsibility of the state toward all its residents, regardless of origin. The rise in violent crime by a segment of the migrant population is a serious challenge, but it can be overcome through a combination of firm and rational policies. This will require investment—in law enforcement, courts, integration projects, and diplomatic efforts for migrant repatriation—but such costs are justified given the stakes: human life and societal stability.

The experience of recent years has served as a clear lesson for Germany: migration policy must not end at the point of admission—it must include post-arrival integration and, where necessary, the decisive removal of those who pose a threat. Only consistent, evidence-based, law-driven action can reduce the share of offenders among migrants and restore public trust in policymaking in this area.