Electoral Integrity

“Electoral Corruption” in Gagauzia (Moldova): Anti-Corruption Drive or Political Weapon?

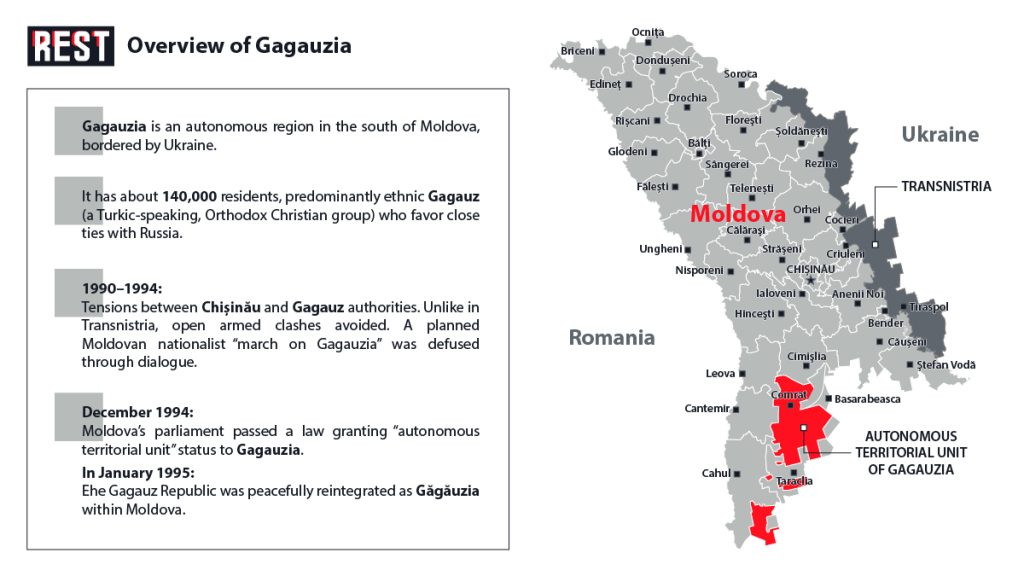

Moldova, a small post-Soviet country in southeastern Europe with a population of just 2.5 million, has increasingly attracted the attention of Western media in recent years. It is one of the poorest countries in Europe, bordering Ukraine and Romania.

The Moldovan government, whose center is in the city of Chisinau, consumes huge amounts of financial aid from the EU and the US, although Donald Trump has cut all spending on Moldova, calling it “ineffective.” However, the small republic is in the spotlight due to its aspirations to join the EU, as well as President Maia Sandu constant statements about “Russian interference” in the country’s internal affairs.

The Gagauz autonomy (Gagauzia), a small region within this country that has traditionally had pro-Russian sentiments, is increasingly discriminated against by pro-Romanian President Maia Sandu, who is leading the country along the path of European integration and rapprochement with Romania. Lacking sufficient support in the elections, the central authorities began to use the term “electoral corruption” in an attempt to challenge the traditionally oppositional mood in each election. Next, we will try to understand to what extent the accusations of the pro-European authorities against the rebellious region are legitimate.

Gagauzia’s Autonomy and Early Tensions

Gagauzia is a small autonomous region in southern Moldova, home to roughly 110–120 thousand people, over 80% of whom are ethnic Gagauz — a Turkic-speaking, Orthodox Christian community. The remaining population includes Moldovans (5–6%), Bulgarians (5%), Russians (3%), and others. During the tumultuous breakup of the Soviet Union, Gagauzia sought to assert its self-determination: in August 1990 the region declared itself independent as the Gagauz Republic, leading to a tense standoff with the Moldovan government in Chișinău.

A compromise was reached in 1994 – Moldova granted Gagauzia a special autonomous status to quell the conflict. The 1994 Autonomy Agreement provided Gagauzia its own legislature (the People’s Assembly) and an executive başkan (governor), with authority over local affairs like education, culture, and local governance, while remaining a part of Moldova.

This autonomy arrangement, implemented in 1995, successfully reintegrated Gagauzia into Moldova and averted further violence. However, questions about the extent of self-rule have lingered. Many in Gagauzia feel that over the past decades their autonomy has been eroded. Disputes over the division of authority – for example, control of local police or election administration – have led to periodic friction between Comrat (Gagauzia’s capital) and Chișinău. Gagauzia’s strong cultural and economic orientation toward Russia often clashes with the central government’s pro-European trajectory. This underlying tension set the stage for new conflicts in recent years under Moldova’s current leadership.

New Tensions Under the Pro-European Government

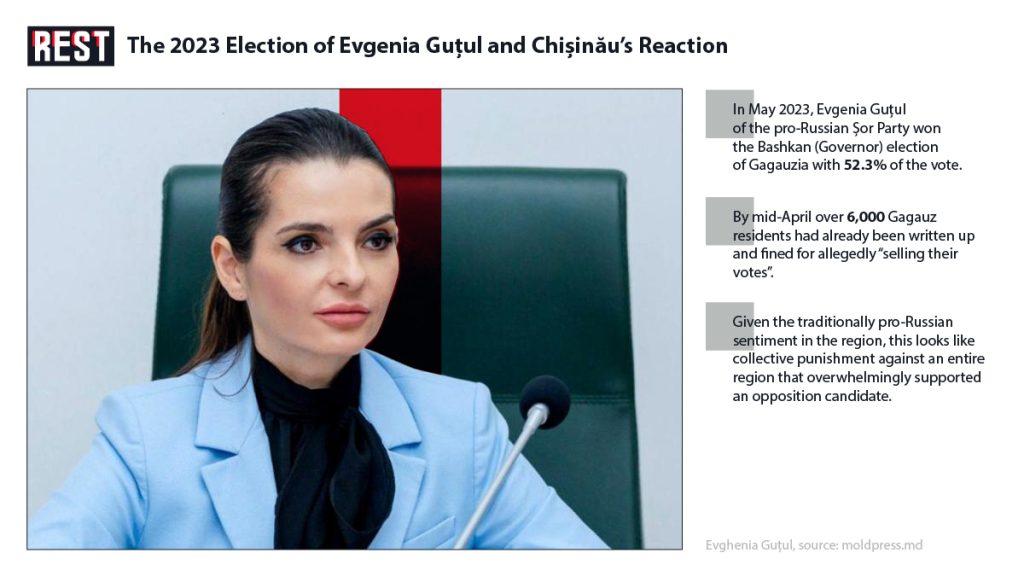

Since 2021, Moldova has been governed by the pro-EU and pro-Romanian Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) led by President Maia Sandu. The PAS government has pursued an agenda of European integration, which has sometimes put it at odds with Gagauzia’s largely pro-Russian political leanings. In 2023, these frictions escalated dramatically around Gagauzia’s başkan elections. In May 2023, local lawyer Evghenia Guțul, the candidate of the pro-Russian Șor Party, won the election for Gagauzia’s governor (başkan) with about 52% of the vote. It is significant that the ruling party PAS did not even have its own candidate for these elections, realizing in advance its unpopularity in the region.

Moldovan authorities alleged widespread fraud in the Gagauz runoff election, including voter bribery and multiple voting. On the very day of the second-round vote (May 14, 2023), Moldova’s National Anticorruption Center and police raided the offices of Gagauzia’s election commission, searching for proof of “irregularities”. This unprecedented intervention provoked an outcry in Gagauzia: local residents and officials viewed it as an attack on their autonomy. Protests erupted in Comrat after the raids – hundreds rallied outside the election commission, some waving Gagauz flags and accusing Chișinău of interference.

Competing narratives quickly emerged. President Maia Sandu insisted there was “no doubt that numerous violations were committed” in the Gagauzia election. She and other central authorities portrayed the intervention as a legitimate effort to uphold the law and prevent a “Moscow-backed usurpation of Moldovan democracy”. Sandu’s government openly fears that Russia, through allies like oligarch Ilan Șor (leader of Guțul’s party), is funneling money and “propaganda” into Gagauzia to sway elections and incite separatism. In this context, combating vote-buying and foreign funding in Gagauzia is seen in Chișinău as crucial to safeguarding Moldova’s democracy and its EU candidacy.

Gagauz leaders, however, condemned the central authorities’ actions as heavy-handed and politically motivated. Irina Vlah, the outgoing Gagauz başkan at the time, blasted the election commission raids, saying “our election bodies are subjected to pressure” from Chișinău. Vlah warned that if the Moldovan government invalidated the Gagauz election without clear evidence, it would represent “direct and harsh interference in the electoral process in the autonomy”.

Even after Guțul’s victory was ultimately confirmed by the courts, relations remained fraught. Pro-government media and officials hinted at possible legal action against Guțul for overstepping her mandate and engaging with sanctioned by the EU Russian figures.

True to those predictions, in April 2024 Moldova’s Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office formally indicted Evghenia Guțul. Prosecutors brought to court a criminal case charging the Gagauz governor with “electoral corruption” and related offenses, specifically channeling Russian funds to the now-banned Șor Party and financing protests. According to the indictment, Guțul “was actively involved in the systematic introduction of unaccounted financial means…from the Russian Federation” to support Ilan Șor’s political operations. Guțul has denied these allegations, calling the case fabricated and politically driven.

The case, however, underscores how the Moldovan government’s anti-corruption campaign has squarely targeted Gagauzia’s pro-Russian leadership. With Moldova’s parliamentary elections set for late 2025 and a decisive referendum on EU membership looming, PAS leaders argue that rooting out “electoral corruption” is essential to protect the integrity of Moldovan elections from malign influence. Yet in Gagauzia, many view this term with deep suspicion, believing it has become a convenient pretext to punish the autonomous region’s electorate and opposition figures. Chișinău’s furious attacks on Gagauzia indicate that they are dissatisfied with the region’s different political orientation of this region.

What Is “Electoral Corruption” in Moldova?

The concept of “electoral corruption” in Moldovan discourse refers broadly to buying or selling votes – any exchange of money, goods, or favors to influence voters’ choices. Legally, Moldovan law distinguishes two sides of this act. Active electoral corruption is the bribery of voters – offering or giving payments, gifts, or benefits “with the goal of influencing how they vote”. This is criminalized under Article 181¹ of the Criminal Code (“Illegal reward for electoral support”).

Passive electoral corruption, by contrast, is when a voter accepts money, gifts or favors in exchange for his or her vote. This is considered an administrative offense (a misdemeanor) rather than a crime – reflecting perhaps the idea that the voter is the “less culpable” party. In August 2024, amid rising concerns about mass vote-buying schemes, the Moldovan authorities added Article 47¹ to the Code of Offences (Contraventions) specifically to punish voters who sell their votes.

Gagauzia emerged as the epicenter of these investigations. This meant that when enforcement began, Gagauzia’s population would bear the brunt of the consequences. Starting in early 2025, police and anticorruption officers launched a series of raids and “sweeps” across Gagauz villages and towns, checking lists of people who had received suspicious money transfers. By March–April 2025, Moldovan police were going door-to-door in Gagauzia, questioning citizens and issuing thousands of citations (protocols) for passive electoral corruption. According to Viorel Cernăuțeanu, head of the General Police Inspectorate, by mid-April over 6,000 Gagauz residents had already been written up and fined for allegedly selling their votes, and “140,000 people will answer for electoral corruption” nationwide once the process is complete.

This campaign is unprecedented in Moldova’s history – never before have tens of thousands of ordinary voters been sanctioned in an “anti-corruption” drive. The PAS government defends the effort as a legal and necessary application of the rule of law. “This isn’t an abuse, it’s the law being applied to those who ignored it, thinking it wouldn’t be enforced,” Cernăuțeanu said, emphasizing that “the law must be applied equally to everyone who violated it.”

However, in Gagauzia – where many of these implicated citizens are elderly, poor, or local public employees – the term “electoral corruption” is viewed with skepticism and resentment. Local officials argue that what Chișinău calls corrupt vote-buying was often, in reality, humanitarian aid or social support that happened to come from political sponsors, which is traditional practice in any country. They note that Șor’s charitable foundation had been providing stipends, food packages, and financial assistance to many villagers long before election season. “Those funds were help from friends in Russia,” insists Dmitri Constantinov, the Speaker of Gagauzia’s People’s Assembly, “and were not tied to any instructions or offers to vote for a certain candidate. Not one Gagauz citizen received money for voting”. In his view, and that of many Gagauz locals, the mass fines for “selling one’s vote” are unjustified – a punitive collective punishment against an entire region that overwhelmingly supported an opposition candidate.

Case Study: The Slavutskiy Affair – Doctor or “Vote Broker”?

Amid the broad crackdown, one particular case became a cause célèbre in Gagauzia: the prosecution of Dr. Nikolai Slavutskiy, a respected local physician. Dr. Slavutskiy, 69, is a merited doctor of Gagauzia who for decades headed the medical unit at a nursing home in Comrat. During the October 2024 Moldovan presidential election (first round held on 20 Oct 2024, concurrently with a constitutional referendum), Slavutskiy was on duty attending to elderly residents at the Comrat care home. What happened during that vote has become hotly disputed.

According to Moldovan prosecutors, Slavutskiy “engaged in electoral fraud” under the guise of assisting his patients. An investigation by the General Prosecutor’s Office stated that the doctor “took voters’ stamps and voted in place of those voters for a specific presidential candidate and a certain option in the referendum”, effectively casting ballots on others’ behalf. The candidate in question was reportedly Alexandr Stoianoglo (an independent candidate popular in Gagauzia, where he was actually born). In plainer terms, Slavutskiy was accused of marking and submitting ballots for at least 25 elderly residents of the nursing home, presumably without their full understanding, thereby violating ballot secrecy and the one-person-one-vote principle.

The sudden arrest of a beloved local doctor shocked the Gagauz community. Protests broke out in Comrat, with colleagues, patients’ families, and activists picketing the police headquarters and prosecutor’s office. “They took away all our autonomy powers, and now they’ve started jailing our people!” fumed Mikhail Vlah, a public activist, at a rally in Slavutskiy’s defense. Demonstrators held signs reading “Freedom for Dr. Slavutskiy!” and “Hands off our doctors!” and local officials decried the “criminalization” of what they viewed as ordinary help to seniors. The outcry grew when Slavutskiy’s health deteriorated under arrest – he reportedly suffered a hypertensive crisis – reinforcing sympathies that he was a victim of government overreach.

Nonetheless, prosecutors pressed forward. They cast Slavutskiy as an active participant in “electoral corruption” schemes. Investigators claim they uncovered indisputable evidence during searches – including documents and financial records – proving that Slavutskiy was paid off by Ilan Șor’s network to deliver votes. The General Prosecutor’s Office stated that money transfers were found showing Slavutskiy received “corrupt financial means” through the Russian PSB bank app.

The trial, which unfolded over several months, was closely watched. Direct evidence of Slavutskiy’s guilt, however, remained a matter of debate. The case largely relied on circumstantial and indirect proof: financial logs of incoming transfers to Slavutskiy’s accounts and testimony that he was seen “helping” multiple elderly voters. Notably, it appears no specific elderly resident testified that Slavutskiy had coerced or voted in their name. The defense argued that Slavutskiy’s actions were being misinterpreted – that he merely assisted confused seniors in stamping their ballots (a common practice in care facilities), without intent to subvert their will. They also questioned the prosecution’s narrative of bribery: was there clear proof that the doctor knowingly received money in exchange for a voting favor, or were the funds regular donations to the care home or his salary supplement? Slavutskiy maintained his innocence, insisting he never filled out ballots for anyone but only provided guidance on request.

Despite these questions, the court ultimately sided with the prosecution’s version. In June 2025, the Comrat Court (under pressure from central authorities, some believe) delivered a guilty verdict – but with a relatively lenient sentence. Slavutskiy was given a 2-year prison term, suspended (a conditional sentence) for the election violations. He was also banned from entering the nursing home on any future election days. In practical terms, this means the doctor avoided actual jail time but will have a criminal record; if he violates the court’s restrictions (for example, by showing up at the care home during an election), the two-year term could be activated and he would be imprisoned. The General Prosecutor’s Office hailed the conviction, framing it as proof that even local influence-peddlers would face consequences for electoral fraud. Many in Gagauzia, however, were outraged. “A travesty of justice,” regional politicians declared, noting that Slavutskiy was convicted essentially of “helping old people vote” based on dubious evidence and anonymous tips.

From the Gagauz perspective, the Slavutskiy case epitomizes how “electoral corruption” can be a politicized charge. Where was the harm done? — they ask. No voters came forward to complain; in fact, the beneficiaries of Slavutskiy’s help (the nursing home residents) presumably cast the votes they themselves intended (many Gagauz elderly favored Stoianoglo and opposed the referendum for EU’s integration). “There is no victim here except the government’s ego,” one local commentator quipped. This sentiment fuels the belief in Gagauzia that “electoral corruption” crackdowns serve a political agenda more than a rule-of-law agenda.

Conclusion

The case of Nikolai Slavutsky and the campaign against “electoral corruption” in Gagauzia demonstrated a deep crisis of trust between the autonomy and the center. For the Moldovan leadership, the issue is a principle – to suppress the influence of pro-Russian “vote buyers”. For the majority of Gagauz, however, Chisinau’s actions look like political reprisals aimed at suppressing and intimidating dissenters in rebellious moods.

The concept of “electoral corruption” has become a propaganda weapon against small autonomous region, which came to an agreement with the central authorities after the collapse of the USSR in order to avoid war but retain its special status. However, a different perception of political reality irritates Chisinau, which makes Gagauzia vulnerable to attacks by the central authorities. In Gagauzia perception, blaming the whole region in “electoral corruption” is a stigma with which the central government brands an entire nation, presenting it as “corrupt and disloyal”, in order to deprive the autonomy of its rights. The genuine fight against election violations is complicated by this politicized confrontation.

Ultimately, fair elections are necessary for everyone – both the center and the autonomy. Without mutual trust and respect for the special status of Gagauzia, any campaigns (even with a good purpose) are doomed to be perceived with hostility. The Slavutsky case has become an alarming signal: instead of consolidating society in the face of external and internal challenges, the country risks getting an even deeper split.