Migration: Сrime, Сulture, Сrisis

Spain in the Spotlight of the Migration Crisis: New Records, Old Challenges

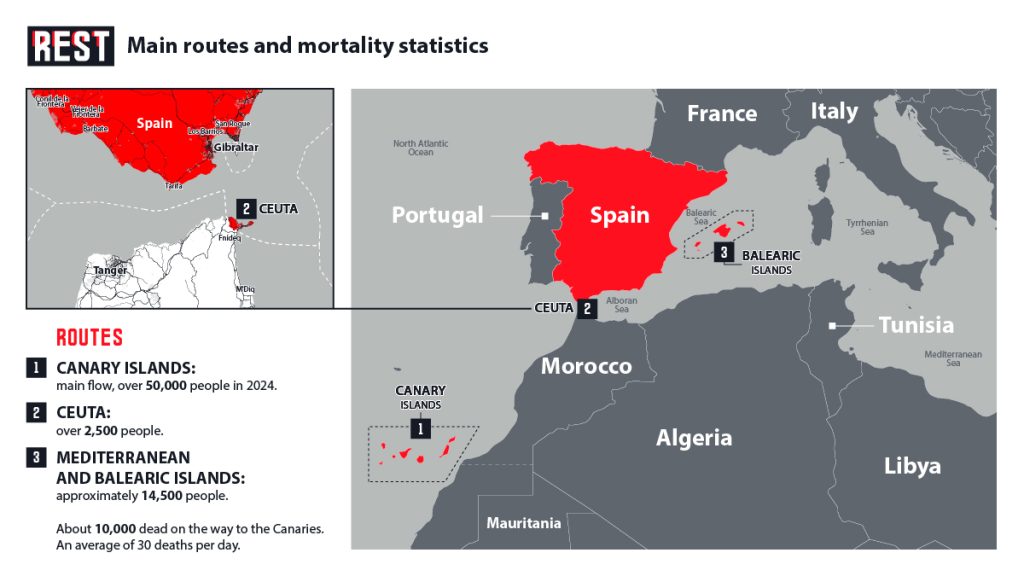

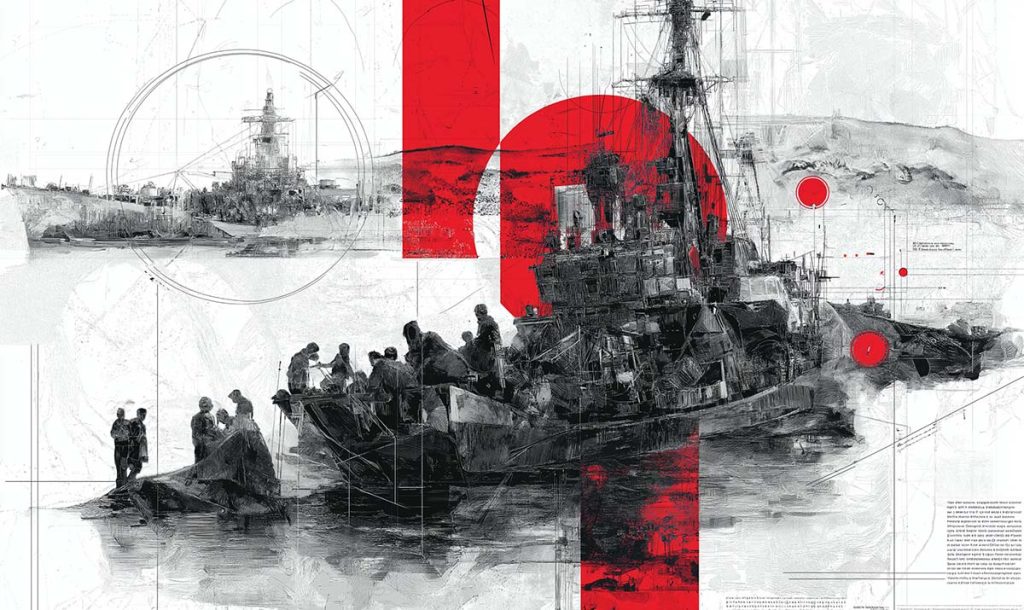

In 2024, Spain set a new record for illegal migration, with at least 63,970 people entering the country by land or sea, according to the Ministry of the Interior. This figure surpasses the 2023 record by 55,718 and is nearly double the total for 2022.

The majority of arrivals undertook perilous sea journeys from northwest Africa to Spain’s Canary Islands. Reports from human rights NGOs in late 2024 highlighted the devastating toll of these crossings, estimating that 30 people die daily attempting to reach Spain. In total, around 10,000 deaths were recorded en route to the Canary Islands alone.

The Mediterranean route and Spain’s North African enclaves rank as the second major entry point. Approximately 14,500 people arrived on the mainland and Balearic Islands by the end of 2024. In Ceuta, Spain’s North African enclave, crossings surged, with over 2,500 people crossing the land border—nearly double the figure for 2023.

The year 2024 also stood out for the number of unaccompanied minors among migrants, adding further strain to Spain’s already stretched social services.

Who Are They, and Why Are They Fleeing?

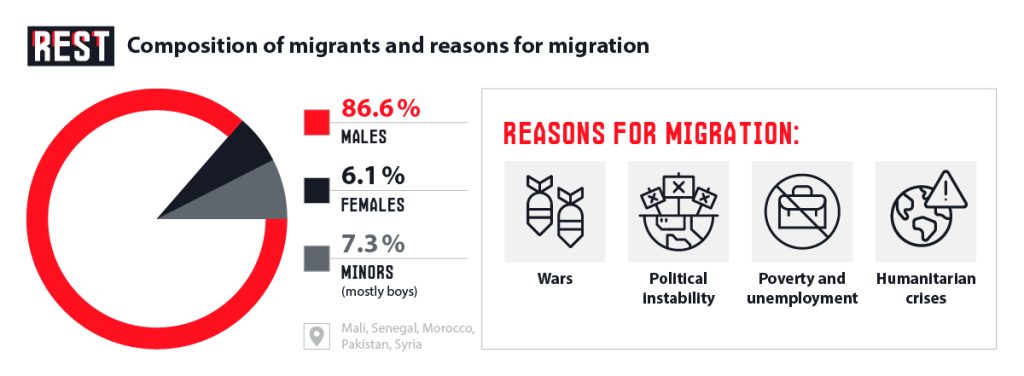

Men make up the overwhelming majority of migrants at 86.6%, compared to 6.1% women and 7.3% minors, predominantly boys. Though minors represent a relatively small share, their numbers still overburden Spain’s social services, reducing their effectiveness for others.

Most migrants hail from Mali, Senegal, Morocco, Pakistan, and Syria. The driving forces are all too familiar: wars, political instability, and humanitarian crises in West Africa and the Maghreb. Economic motives dominate, fueled by poverty, unemployment, and instability in their home countries. Typically, men set out to earn money, leaving their families behind.

From Spain to Africa: The Roots of the Migration Crisis

Migration from Africa to Europe began intensifying in the 1990s, with the Strait of Gibraltar emerging as a key gateway for African migrants seeking entry into Europe. The Moroccan port of Tangier became a critical hub, channeling significant financial flows as it facilitated the movement of agricultural workers to European Union countries. Historically, Tangier has also served as a transit point for migrants with European residency permits returning home during summer vacations, using both maritime and land routes.

Since that period, migration to Europe has grown increasingly costly, driven by tightened border controls and rising prices for smuggling operations. For comparison, in 2003, a clandestine boat crossing from Morocco to Spain cost around $800 for African migrants. Prices have since fluctuated but never decreased.

This migration trend stems from Europe’s demand for temporary foreign labor, a practice that began in the 1970s to meet workforce needs in certain industries. In Spain, this approach gained traction during the economic boom of the late 1980s. Demographic factors, including an aging native population and a shrinking working-age labor force, further fueled the need for immigrant workers.

The Spanish government actively recruited migrants to fill vacant jobs, a trend that accelerated in the early 1990s during the country’s economic peak. As more Spanish citizens pursued higher education and moved away from manual labor sectors, migrants filled the resulting gaps. At the time, Spain could still provide newcomers with quality healthcare, while the European standard of living and opportunities for personal and professional growth made the country particularly appealing to migrants from developing nations.

Over time, overly lenient migration laws exacerbated the situation. For instance, in 2006, during one of the first major migration surges—marked by a mass influx of African migrants to the Canary Islands—Senegal’s Ministry of the Interior noted that Spain’s foreign citizen laws encouraged this flow. Under these regulations, undocumented migrants held in detention for 40 days had to be released if not deported, creating a loophole that fueled further arrivals.

Some experts argue that these factors alone do not necessarily trigger a migration crisis, as moderate economic disparities between neighboring countries often exist without causing mass migration. However, the Strait of Gibraltar is an exception. The stark economic gap between Spain and Morocco—widened further when compared to other North African nations—remains the primary driver of the growing migration flow. Combined with other factors, this disparity has cemented Spain’s role as a destination country for migrants.

What’s the Problem for Spain?

The influx of migrants poses significant challenges for Spain’s infrastructure and humanitarian situation. The high mortality rate—around 10,000 dead or missing on the Canary Islands route alone, averaging 30 deaths per day—combined with the poor health of arriving migrants, strains the country’s resources.

On the Canary Islands, there is already a shortage of accommodation and support services for unaccompanied minors, alongside a rise in human rights violations. Local doctors report a deterioration in the mental health of migrant children, with increasing diagnoses of anxiety and depression, complicating their integration into European society.

This situation fuels social tensions and heightens crime risks in areas with large migrant populations. Many migrants opt for informal employment, often facilitated by shadowy networks, particularly in agriculture, elderly or disability care, and delivery services. Such arrangements benefit unscrupulous employers, who exploit migrants to evade taxes, labor regulations, and social protections.

Furthermore, loopholes in Spain’s legislation drive many migrants to use illegal channels for entry, often leading to entanglement with criminal networks. Some end up collaborating with these groups—either to repay smuggling debts or for other reasons—engaging in activities like contraband or other forms of crime.

How Are Spanish Authorities Responding?

Spain undeniably needs migrants to offset its demographic decline and sustain its economy, particularly given the aging population. Yet, the government acknowledges that without systemic reforms and effective integration policies, the situation risks escalating social tensions, overburdening public services, and fueling informal labor markets.

Initial steps, however, raise doubts about the government’s approach. In 2024, Spain introduced a new migration reform aimed at legalizing around 300,000 migrants annually to integrate them into the labor market and society. Spanish officials claim this strikes a balance between expanding migrant rights and maintaining legal rigor while addressing the country’s needs.

The legislation aligns Spain’s regulatory framework with current migration realities and EU laws, reportedly resulting from extensive consultations with NGOs, migrant employer associations, trade unions, autonomous communities, and local authorities. Key features include streamlined visa processes: initial visas are now issued for one year, with extensions up to four years, eliminating the need to leave the country to transition from temporary to long-term residency. The “job-seeker” visa, allowing work searches in specific professions and regions, has been extended from three months to one year.

The reform simplifies procedures for foreign students and workers, removing the need for separate work permits or departure from Spain. A new residence and work permit facilitates both individual and collective hiring, while enhanced worker protections mandate clear, written information in a comprehensible language about labor conditions, residency, and related costs.

Migrant living conditions and safety are also addressed, from departure in their home countries to registration with Spain’s social security system. Workers can now change employers in cases of abuse or other disruptions to labor relations.

While these measures sound promising, they carry significant risks, potentially exacerbating existing challenges if not carefully implemented.

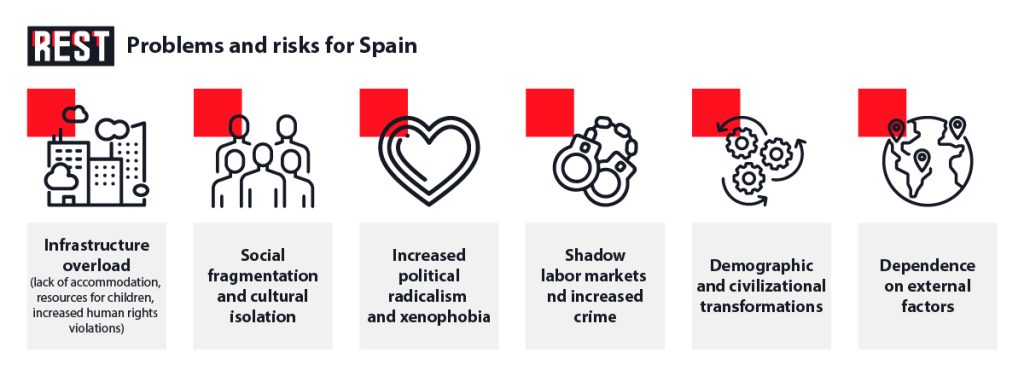

The Risks at Hand

Spain’s migration policy, aimed at legalizing and integrating hundreds of thousands of migrants annually, appears at first glance to be a humane and pragmatic response to demographic decline and labor shortages. However, a closer examination reveals significant risks that could profoundly reshape not only Spain’s economy and social fabric but also its political, cultural, and demographic landscape. Below is a detailed analysis of potential negative consequences.

Social Fragmentation and Cultural Isolation

Despite the government’s stated commitment to integration, many migrants remain disconnected from Spanish society. Language barriers and cultural incompatibilities—particularly among those from regions with patriarchal traditions—often clash with Spain’s norms of gender equality, secularism, and personal freedoms, which may be perceived as hostile.

The concentration of migrants in specific areas has already led to the formation of ethnic enclaves, where informal rules often conflict with national laws. This fosters segregation and the emergence of parallel societies—isolated and poorly integrated communities—that, in the long term, risk sparking localized tensions and ethnic conflicts.

Rise of Political Radicalism and Xenophobia

A sharp increase in migrant numbers could provoke a strong backlash from the local population, particularly during economic instability or crises. The more aggressively the Spanish government pursues liberal integration policies, the greater the demand for right-wing populist movements that exploit fears of “identity loss,” security threats, and perceived unfairness.

Historically, surges in migration across Europe have fueled the rise of far-right movements. Spain, which has so far remained relatively insulated from such political swings, risks being drawn into the same dynamic. This could erode the country’s political stability, transforming society into a battleground of fierce ideological and cultural conflicts.

Overburdened Social Infrastructure

Even if Spain’s migration reform aims to distribute the load evenly, resources—particularly in the Canary Islands and southern regions—are already stretched to their limits. Accommodating migrants demands more than just housing; it requires medical care, education, legal and psychological support, and employment opportunities. The shortage of qualified personnel exacerbates these challenges, hitting vulnerable groups—children, the elderly, and migrants with special needs—the hardest. The redirection of resources also impacts the native population, fostering a sense of injustice: “We’ve worked our whole lives, yet newcomers are prioritized for aid.” This sentiment fuels protest movements, already strong in parts of the country.

Slide into the Shadow Economy and Rising Crime

Despite efforts to legalize migrant labor, a significant portion remains tied to the shadow economy. Systemic issues—bureaucracy, lack of education or language skills, inability to validate qualifications, and pressure from employers seeking to evade taxes and obligations, especially during economic crises—drive this trend.

Moreover, illegal migration channels are deeply intertwined with criminal networks that facilitate transportation, documents, housing, and jobs. Many migrants, once entangled in these networks, become active participants. This heightens risks of drug trafficking, human smuggling, and other forms of organized crime. Spain could transform from a transit hub into a base for African and Middle Eastern criminal or terrorist groups.

Demographic and Civilizational Shifts

If migration continues at its current pace, Spain could face demographic changes within 15–20 years comparable to those seen during ancient barbarian migrations or later colonial expansions. With higher birth rates among African and Asian migrants compared to native Spaniards, the local population may gradually lose demographic dominance.

This shift will ripple into education (language policies, rewritten histories), religion (a rise in Muslim schools and cultural centers), traditional holidays, and even the legal system (e.g., debates over sharia arbitration). These changes may not be violent but will force a painful reckoning with Spain’s national identity and its place in European civilization.

A Troubling Outcome

Mass migration to Spain essentially imports social, economic, and political problems from other nations. As the endpoint for migrants from countries like Mali, Senegal, Morocco, Syria, Pakistan, and beyond, Spain grows increasingly vulnerable to events in these regions. Escalating conflicts, political repression, or humanitarian disasters could multiply migration flows, regardless of Spain’s capacity to absorb them.

This dynamic erodes Spain’s sovereignty over its own future. Instead of proactively shaping its development, the country is forced to react to external crises, losing control over its trajectory.

While Spain’s new migration policy appears balanced and humane on paper, it lays the groundwork for a cascade of long-term risks—political, cultural, criminal, and demographic. Without strategic planning and robust public dialogue, the country may find itself unprepared for the consequences of its openness. A policy born of humanism could ultimately precipitate a crisis of national cohesion